Editor's Note: This text is an edited transcript of the course Vocabulary Interventions for Students with Language Disorders, presented by BeckyAnne Harker, PhD, CCC-SLP.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Explain the importance of vocabulary learning for all students, but especially those with language disorders.

- Describe how to choose target vocabulary and at least two methods for vocabulary intervention.

- Discuss the results of a study of vocabulary intervention for students with language learning disorders.

Agenda

The course agenda is aligned with the learning objectives. We'll begin by covering some background information, including key theories, which, while not always exciting, are both important and interesting. I hope you'll find them engaging as well. We'll then explore how vocabulary relates to comprehension and its connection to other language modalities.

The second part of the presentation will focus on intervention, addressing both the "what" and the "how." Finally, we'll review my dissertation study, as it provides some interesting findings that I’d like to share with you.

Background Information and Theories

Let’s dive right in and discuss some background information and theories. But, we need to start with some statistics. What do we know about vocabulary and vocabulary learning? Children typically learn between 2,000 to 3,000 words each year.

By third grade, students generally know about 10,000 words. That’s quite a lot! However, by fourth grade, a 6,000-word gap emerges, largely based on socioeconomic status (SES). Children from lower SES backgrounds may know around 13,000 words by fourth grade, while their peers from higher SES backgrounds often know closer to 20,000. This gap is significant in terms of the number of words students have in their vocabulary.

Interestingly, only about 300 to 400 words are explicitly taught in schools. And if you’ve ever wondered what your students actually retain, research shows that kindergarteners learn only about 40% of the words taught to them, which translates to learning about 5 to 7 new words per week. This means that for students to learn 400 words, teachers need to target at least 1,000 words per year. That’s quite a lot! Now, let's continue with more stats.

Wanzek and colleagues conducted an interesting study on second-grade teachers, examining the number of words they spoke. They found that these teachers produced 3,764 words per hour—so yes, they talk a lot.

I think it would be fascinating to study how many words SLPs use per hour, because it’s probably even more. But what’s really striking is that while teachers produce that many words, they only use about 1,000 different words, meaning there isn’t much diversity in the vocabulary they’re using. In fact, 84% of the words were common, everyday words, and just 1% were academic words.

The study also found a correlation: the more academic words teachers used, the better their students’ vocabulary scores were by the end of the year. Now, of course, this isn’t causal—correlation doesn’t imply causation—but it’s still worth thinking about. It suggests we might want to focus on using more academic language and expanding the vocabulary we expose students to.

Why Vocabulary?

You're most likely taking this course because you're interested in vocabulary, and perhaps you're not sure of the best way to teach it. When I started my doctoral program, I didn’t set out to become an expert in vocabulary. In fact, in my 25 years of practice, I don’t think I really focused on vocabulary much myself.

But as I worked through my program, I kept reading and trying to figure out how to best help our students, particularly with their comprehension. And no matter what I explored, I kept coming back to vocabulary. Now, I realize just how critically important it is.

I’ve also noticed that there might be a divide in how we view vocabulary instruction. For those of you who graduated more recently, you might already be aware of this. But for those of us who have been in the field a bit longer, like myself, this was something I only learned recently. The National Reading Panel conducted a survey back in 2000 to determine the most important aspects of literacy. And, as you can see, vocabulary emerged as one of the key pillars.

Of course, skills like phonics, reading fluency, and comprehension are essential—they’re the backbone of reading. But vocabulary was specifically identified as its own critical element, a separate pillar in literacy instruction. It’s not just about sounding out words or understanding what you’re reading—it’s about the words themselves and the knowledge behind them.

Another concept I learned only in the past several years, which I wasn’t aware of before, is also foundational to literacy. I really should have known this earlier. The first equation I want to highlight is: R = D x C. This represents the Simple View of Reading, where reading (R) is equal to decoding (D) multiplied by comprehension (C). It’s not a sum, but a product, meaning both elements are essential and work together. This concept forms the foundation of the science of reading.

Scarborough introduced a visual model known as the Reading Rope, which provides a great breakdown of these components. If you’re interested, you can easily look up the graphic for a clear illustration. Scarborough outlines what makes up both decoding and comprehension.

Decoding includes the ability to recognize letters and sounds, phonological awareness (breaking down sounds and blending them together), and sight recognition—because we don’t sound out every single word we encounter. That’s all part of decoding.

Then there’s language comprehension, which is our area of focus. This includes vocabulary knowledge (which, notably, is listed first), background knowledge, understanding of language structures, sentence structure, literacy knowledge, and verbal reasoning. All of these factors are crucial in building students’ reading comprehension skills.

What is Language?

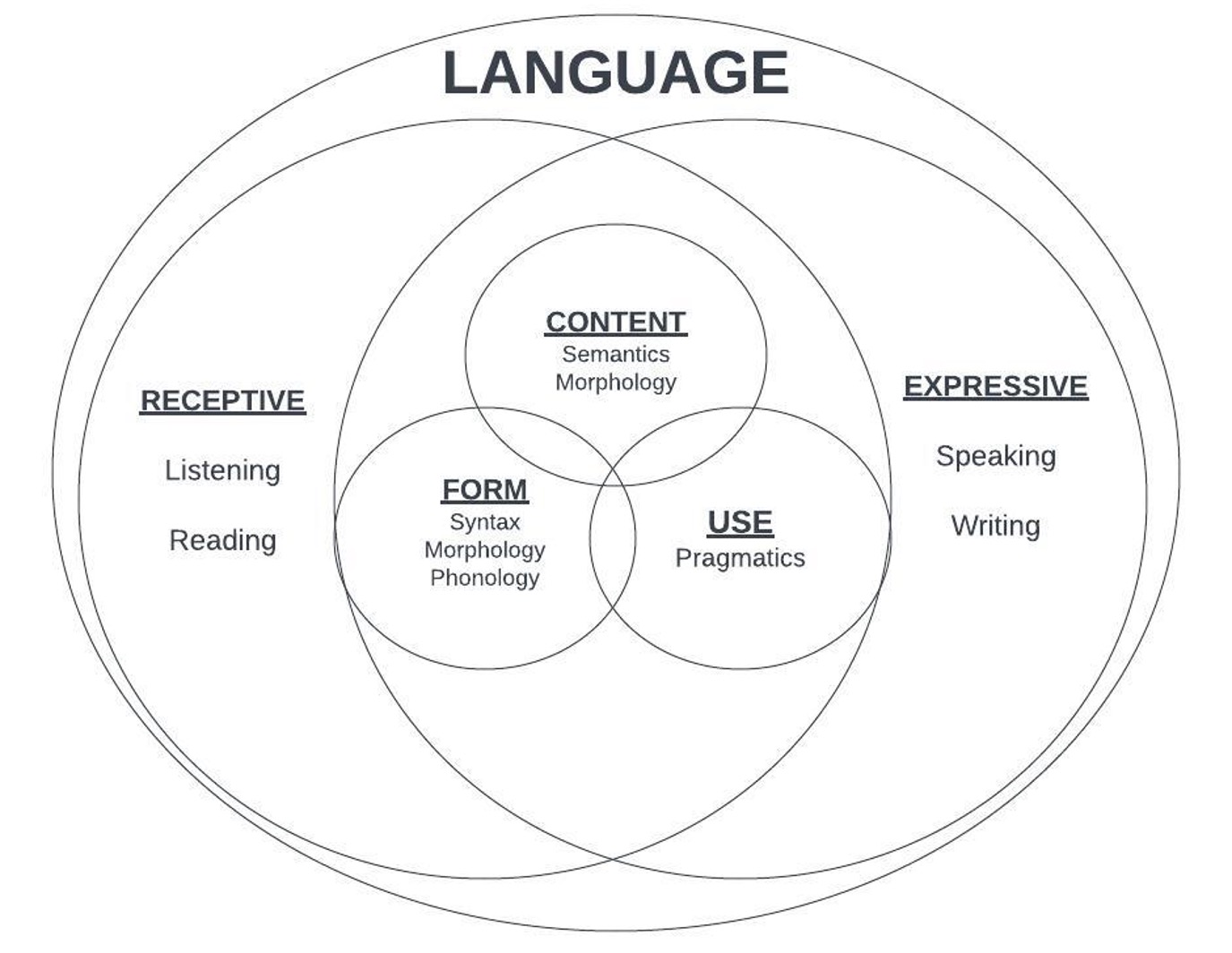

Vocabulary is essential not only for literacy but also for overall comprehension. This is probably no surprise to anyone in this group, but I wanted to share a graphic I developed that reflects how I think about language.

Figure 1. Language Model.

In this model, language is the overarching concept, divided into receptive and expressive components. These days, we understand that the line between these two isn’t so clear-cut, which is why I’ve represented them in a Venn diagram to show how much they overlap.

On the receptive side, we have listening and reading, as reading is a language function—just delivered through the visual modality. On the expressive side, we have spoken language and writing, which is another way of expressing oneself visually. These modalities overlap, and in the center of the diagram, we can consider language in terms of content, form, and use, as we know from language theory.

I’ve highlighted semantics because it’s closely tied to vocabulary. Semantics, which includes vocabulary, also interacts with other areas of language, such as morphology. We’ll dive into these relationships a little more as we go along.

Wazowitz extended Scarborough’s reading rope even further, incorporating both reading and writing, and integrating the oral and written modalities more comprehensively.

In the top half of the model, we focus on the oral language components. On the receptive side, we have language comprehension, and notice what I’ve highlighted here—vocabulary. On the language expression side, again, I’ve highlighted vocabulary. It's essential on both sides. But also, look at how all of these components come together: background knowledge, language structure, verbal reasoning, literacy knowledge, and, importantly, pragmatics. These are the strands in Scarborough’s reading rope that fall under comprehension.

In the bottom half, we shift to the written language modality. On the left, we have reading as the receptive task, and on the right, we have writing as the expressive task. And once again, I’ve highlighted semantic awareness—because vocabulary and knowledge of meaning are crucial not just for reading, but also for writing. Vocabulary plays a central role in both modalities, tying directly into literacy development.

This reinforces the idea that vocabulary is woven throughout all aspects of language—whether it’s oral or written—and that it’s a critical component of literacy.

Newsflash!

Reading disabilities are, in fact, language disabilities because reading is simply a written form of language. I want to pause here for a moment and look ahead, specifically to a term I used in my dissertation. I referred to the students I worked with as having language learning disabilities (LLDs). Now, I know that in our field, there’s been a push towards using the term developmental language disorder (DLD) more frequently.

However, I deliberately chose the term language learning disorder for my research because I wanted to include students who have reading disabilities or learning disabilities related to reading, which are fundamentally language-based. When we talk about developmental language disorders, we often focus on the students we typically see in our clinical settings. But there’s another group—students with reading disabilities—who also have language weaknesses that are connected to their reading difficulties.

By calling it a language learning disorder in my study, I aimed to encompass both groups: those with traditional developmental language disorders and those with reading disabilities stemming from language-based challenges. We’ll dive deeper into this concept when we discuss the findings from my dissertation later on.

Children with Language Disorders (McGregor et al., 2021)

This course focuses on students with language disorders, specifically, and what we know about their vocabulary learning. Well, we know that learning new vocabulary is an area of difficulty for them. This challenge stems from weaknesses in verbal memory and executive functioning. These students struggle to recall words effectively and have trouble focusing on verbal input. I know it can be frustrating at times when it feels like students aren’t paying attention, almost like they’re hearing us as the “Peanuts” teacher, with everything sounding like “wah-wah.” They’re not always actively engaged in learning the material we present, and this directly impacts their ability to acquire new vocabulary.

Another challenge they face is having smaller semantic networks. This means that even when they learn a new word, they only grasp it on a shallow level. They don’t make the rich connections between words that would help deepen and solidify their understanding. As a result, they have less breadth (fewer words overall) and less depth (a more superficial understanding of the words they do know). They’re unable to see how a word might apply in different contexts or recognize subtle nuances in meaning.

This means that these students need more repetition of vocabulary words and their definitions in order to learn effectively. Due to their memory and executive functioning difficulties, they require us to provide frequent practice and expose them to these words in different contexts so they can build those semantic networks. By doing this, we can help them develop a more robust understanding of the vocabulary they’re learning.

The Matthew Effect (Stanovich, 1986)

The Matthew Effect is another concept I came across during my research, and I think it’s likely familiar to some of the younger SLPs out there. It was new to me when I stumbled upon it, but it resonated deeply and drove much of my interest in vocabulary research. The Matthew Effect essentially means "the rich get richer, and the poor get poorer." In our case, it’s particularly relevant to vocabulary development.

In terms of vocabulary, the Matthew Effect suggests that if a child starts off with a strong language base—let’s say in kindergarten—they're likely to be drawn to language-rich activities. These children enjoy looking at books, reading, talking with peers, engaging in conversation, playing rhyming games, and participating in other language-based activities. The more they engage in these activities, the better their language becomes, reinforcing itself over time.

Now, what does this mean for our students with language disorders? They often begin with a weak language foundation, and as a result, they tend to avoid language-based activities. They don’t want to sit down and listen to books or engage in extended conversations with their peers. Instead, they might prefer more physical play and steer away from the types of activities that promote language growth. This avoidance means their language skills stay weaker, and the gap between students with strong language abilities and those with language weaknesses widens over time.

The Matthew Effect really illustrates how early language skills—or the lack thereof—can set a trajectory that continues to impact a child’s vocabulary development, creating a widening divide between those with strong language foundations and those without.

Some Theories of Vocabulary and Comprehension

So, it’s great to learn new words, but so what? For me, the "so what" is comprehension. The whole point of being able to read and communicate is to understand—whether it’s understanding what you’re reading or what others are saying. This led me to explore how vocabulary and comprehension interact, and I found that there are many different hypotheses out there—about 25 if I remember correctly.

However, I focused on the three that resonated most with me and directly shaped how I approached my research. These hypotheses really helped me narrow down my focus on the relationship between vocabulary and comprehension, and they guided my investigation into how improving vocabulary could also enhance overall understanding for students with language difficulties.

In the end, it’s not just about building up a long list of words—it’s about helping students make meaningful connections so that those words contribute to their ability to comprehend, both in reading and in communication.

Instrumental Hypothesis (Anderson & Freebody, 1981)

The Instrumental Hypothesis essentially means that vocabulary serves as an instrument of comprehension. It makes perfect sense, right? You need a certain level of vocabulary knowledge in order to understand what’s being communicated. If I said a sentence with three words you didn’t understand, you’d probably have no idea what I was talking about.

This hypothesis is backed by empirical evidence, and it’s more than just a logical assumption—it’s been shown to have a causal relationship. Studies have demonstrated that when you teach children new words, they can then understand sentences that contain those words. This finding isn’t just from a single study; it’s been confirmed through meta-analysis, meaning it holds true across multiple studies.

Knowledge Hypothesis (Anderson & Freebody, 1981)

The second hypothesis is the Knowledge Hypothesis, also proposed by Anderson and Freebody, who developed three hypotheses that work together. This one suggests that vocabulary and comprehension are related through background knowledge—hence, the "knowledge" in the hypothesis.

In this case, vocabulary does contribute to comprehension, but it’s actually tied to all the other background knowledge you have. This is why building semantic connections is so critical. As you expand your understanding of a topic, you’re also expanding your vocabulary, which improves your overall comprehension.

When teaching vocabulary, it’s essential to teach multiple semantic connections, because they act as a proxy for background knowledge. Let me give you an example: the word "lathe." When I was in upper elementary school, I came across the word in a book, but I had no idea what it meant, and the context didn’t help me figure it out. So, I looked it up, and the definition was: “a machine in which work is rotated about a horizontal axis and shaped by a fixed tool.”

Now, I understood every word in that definition—machine, work, rotated, horizontal, axis, shaped, fixed, tool—but it still didn’t help me grasp what a lathe actually was. I didn’t have the background knowledge to fit it into my mental schema of what a machine does.

For those who don’t know, a lathe is a woodworking tool that spins material on a horizontal axis, and you use a chisel to shape the material into round objects, like baseball bats, spindles, or bowls. Without that woodworking knowledge, all those individual words in the definition weren’t enough to make sense of it. That’s just a small example of how background knowledge plays a huge role in understanding vocabulary.

In essence, vocabulary doesn’t just stand alone—it’s tied to everything else we know, which is why teaching those connections is so important for comprehension.

Reciprocal Hypothesis (Stanovich, 1981)

We’ve already touched on the Reciprocal Hypothesis, which states that vocabulary and comprehension have a reciprocal relationship. This is essentially the Matthew Effect in action. The less vocabulary you know or the lower your language abilities, the fewer language and reading exposures you have. As a result, you miss out on countless opportunities to learn new words, and the gap between students with strong and weak language skills continues to widen over time.

This reciprocal relationship means that as language skills lag, so do opportunities for growth, which only makes the problem worse. This is why it’s so crucial that we focus on building vocabulary early and consistently to help our students. By strengthening their vocabulary, we also improve their overall comprehension, breaking the cycle of missed opportunities and helping to close that knowledge gap.

Vocabulary Interacts with Other Language Modalities

Another important area I wanted to explore is how vocabulary interacts with other language modalities. While some of this might not be groundbreaking news, I did find certain aspects really intriguing. Specifically, we’re going to discuss how vocabulary connects with phonology, morphology, and background knowledge.

Vocabulary and Phonology

When I think about our field, I’ve often viewed speech and language as separate—speech over here, and language, divided into receptive and expressive, over there. But they actually interact, as we store words both semantically and phonologically. For example, if you hear a name you’ve never encountered before, especially from another culture or language, it might not be very complicated, but it’s unfamiliar. In such cases, I often ask, "How do you spell that?" Once I see the word or name written out, I can store it in my brain more easily and recall it later.

For instance, my daughter's name is Amani. It’s Arabic, and many people trip over it at first. They might say, "Amanda?" or ask how it starts—"Is it Amani with an A, an I, or a U?" It’s spelled A-M-A-N-I. Once you see it written, you can store it in your brain, and you’re more likely to remember it.

Studies have shown this interaction between phonology and memory. Words containing later-developing sounds (the “late eight” sounds) are recalled less often than those with earlier-developing sounds. This makes sense—shorter words are easier to recall than longer ones with more syllables because there’s less to store phonologically. Even children who know their letters and sounds struggle to read words they don’t already know.

Ouellette (2006) found that a better vocabulary helps increase phonological awareness. If you're storing words based on their sounds, you'll be able to discriminate between similar-sounding words more effectively. But we know our students often struggle with recalling sounds, encoding new words, and storing the sounds of new words. They need help with this process.

When thinking about vocabulary, phonology, and reading, Ouellette also found that students with a stronger receptive vocabulary are better at decoding words, while a stronger expressive vocabulary correlates with better sight word reading. While I’m not entirely sure what this means for the rest of us, I found it fascinating that they were able to draw these correlations.

Vocabulary and Morphology

This shouldn’t be entirely new because morphology is the study of word parts, and meaning is semantics, which is essentially vocabulary. So, it’s all connected. Morphological knowledge—understanding prefixes, suffixes, and root words—has been shown to predict reading comprehension across multiple languages, not just in English. When students understand word parts, they can comprehend text more easily. It helps with overall reading because they’re able to chunk letters and sounds, allowing them to read more fluently without relying on sounding out every single letter or sound.

Knowing prefixes, suffixes, and root words also enhances background knowledge, which, as we’ve discussed, is critical for comprehension.

Think back to when you took the ACT, SAT, or even the GRE for graduate school. In the vocabulary or reading sections, sometimes it felt like they had made up words just for the test. But one strategy I remember using was analyzing the prefixes and root words. For example, if a word started with “un-,” I knew that meant “not,” and if the root looked familiar, I could make an educated guess. Whether or not I got those questions right, that strategy was grounded in my understanding of morphology and background knowledge.

As students get older, the texts they encounter contain increasingly morphologically complex words, which makes morphological knowledge even more important. When students have a good grasp of morphology, they don’t need every word explicitly taught to them—they can figure out new words incidentally by breaking them down into familiar parts. This allows them to learn vocabulary more naturally and efficiently, which is key as they progress to more advanced texts.

Morphology Examples. You’ve probably all seen a long word that, if you had to sound it out letter by letter, you’d be stuck on it until next Tuesday. But instead of sounding out every letter, you can break it down into morphemes that you recognize. For example, take a word like antidisestablishmentarianism. Rather than sounding out the whole thing, you can pick out familiar morphemes: “anti,” “dis,” “establish,” “ment,” “arian,” and “ism.” Once you break it down, you can recognize and read the word much faster. Plus, you can figure out the meaning—“anti” means against, “dis” adds a layer of opposition, and “establishment” refers to the institutional order. So the word essentially refers to opposition to the movement against the established church. And “ism” indicates a belief system. It’s a complex word, but by knowing the parts, you can decode it and grasp its meaning.

Another fun example is hemidemisemiquaver. I didn’t know what a quaver was at first—and I’m guessing most people don’t. It’s actually a British musical term, and even though I’m a musician, I hadn’t come across it before. A quaver is an eighth note. Knowing that “semi,” “demi,” and “hemi” all mean fractions or halves, you can deduce that a semiquaver is a sixteenth note, a demisemiquaver is a thirty-second note, and a hemidemisemiquaver is a sixty-fourth note, which is incredibly fast!

Vocabulary and Background Knowledge

Moving on to vocabulary and background knowledge, we know that students learn words better within familiar contexts. There’s a famous study where students who struggled with reading and language tasks, but had a strong interest in baseball, were able to read and learn new words when reading about baseball. It seemed almost miraculous because the context made sense to them. This shows that just pulling random words out of the air to teach won’t be as effective. But when the vocabulary is tied to something they already know, it becomes much easier to learn.

Background knowledge provides a foundation for learning. I mentioned earlier how semantic networks help connect words together. When students have a solid background in a subject, new words can be linked to that knowledge, making them easier to remember and understand. In fact, studies have shown that vocabulary and background knowledge are highly correlated as early as kindergarten.

Another key aspect of background knowledge is its role in helping students make inferences. I’ve set goals for students to improve their inferencing skills, which is a cognitive ability in itself. However, if a student lacks the necessary background knowledge, they won’t be able to make that leap to fill in gaps and guess the meanings of unknown words.

I remember when my daughter Amani was in fourth grade and learning about government. She came across terms like "executive branch" and "legislative branch." Even though the teacher likely explained them, those words didn’t mean much to her at the time because she didn’t yet have the background knowledge to understand how government worked. Without that foundational understanding, those terms remained abstract to her. Building that background knowledge is key to helping students learn and retain new vocabulary.

I also looked to see if there were any studies showing whether teaching vocabulary directly increases background knowledge. While we’ve seen how background knowledge affects vocabulary acquisition, I was curious if the reverse is true—whether improving vocabulary enhances background knowledge. I didn’t find any studies that explicitly confirmed this, likely because measuring background knowledge is a bit tricky. However, studies have shown that the two domains are highly correlated, and there’s some evidence to suggest that improving vocabulary can indeed support the growth of background knowledge.

That said, it’s important to recognize that teaching vocabulary alone might not be enough, especially in cases like the government example I mentioned earlier with my daughter Amani. Simply learning terms like "executive branch" and "legislative branch" doesn’t necessarily build the deeper understanding needed to grasp government systems. You often need to work on building background knowledge alongside vocabulary instruction, using words and concepts students are already familiar with to scaffold that learning.

Interventions: What and How

Vocabulary in Speech and Language Therapy (Justice et al., 2014)

This particular study, which is about ten years old now, by Justice et al., looked at how SLPs teach vocabulary. What they found was that 87% of us—yes, I’m including myself—do not target vocabulary in the most effective way. We’re not selecting the best types of words, and we’re not using enough components of evidence-based practices for explicit vocabulary instruction.

We do some good work. We use our skills, but it’s not enough. And honestly, I’m 100% guilty of this. As I mentioned earlier, I didn’t start out in this field because I had a passion for vocabulary. In fact, I often feel overwhelmed by vocabulary because there are so many words out there—where do you even begin?

I remember attending a workshop on vocabulary instruction about a year ago. We discussed common strategies, like teaching synonyms, antonyms, categories, similarities, and differences. At one point, the presenter asked us, "How did you know to teach vocabulary this way?" And we all just kind of looked around, unsure. No one had explicitly taught us to approach vocabulary that way. Maybe we picked it up from other people’s goals or from workbooks, but it turns out that this isn’t really the most effective method. I didn’t know that until recently.

As I said, the sheer number of words can be overwhelming. If a third-grader knows around 10,000 words, how do you even decide which ones to target? In 2002, Beck and colleagues introduced the concept of three tiers of vocabulary words, which provides a framework to help prioritize.

- Tier-one words are the everyday, basic words that children pick up naturally, just by hearing them in conversation. These are words like pencil, hurry, or ugly. No one really sits down and teaches kids what "ugly" means—they learn it because it’s part of everyday language.

Tier-two words are more difficult and less common in everyday speech, but they appear frequently in written language and across different contexts. These might be words like forbid, bask, or intend. You’ll see them in novels, science texts, social studies, and so on. These are the words that show up across subjects but aren’t as commonly used in conversation.

Tier-three words are highly specialized, context-specific terms. Examples include hypotenuse, aorta, and thesis. They appear in specific lessons, introduced by teachers in the context of a particular subject, such as biology or geometry.

The problem is that many of us tend to focus on tier-one or tier-three words, but it’s those tier-two words that often get missed. Yet, these are the words that can really enhance students’ understanding across different contexts and help them bridge the gap between basic vocabulary and more complex, subject-specific language.

Choosing Words

When choosing vocabulary to target, we really need to focus on tier-two words. Let me share a quick anecdote. Early in my career, I was working at a high school, and one of my students, a freshman girl with a learning disability in reading and language goals, brought her social studies book to our session. I thought, "Great, we’ll use this to work through her vocabulary." We started reading the introduction paragraph, and I quickly realized we couldn’t even get through it. She didn’t understand half the words—and they weren’t the bolded content words specific to the subject. This was just the introduction, filled with tier-two words she didn’t know. As a result, she couldn’t grasp the basic premise of what the chapter was about.

At that moment, I felt overwhelmed and thought, “Where do we even start?” Unfortunately, it took me almost 20 years to figure it out: we need to focus on those tier-two words. These are the words that students will encounter frequently across different subjects, but they’re not often explicitly taught. Without a solid grasp of them, students can’t fully comprehend texts, even before they get to the content-specific vocabulary.

But pulling words out of thin air isn’t helpful. We need to choose words from some kind of context. In my own work, I often use storybooks. I challenge any of you to pick up a children’s storybook—something with an actual narrative, not just simple early-reader books—and try to find tier-two words. For my study, I selected eight storybooks aimed at third-grade readers. Each one had at least seven tier-two words that my students didn’t know. It’s a simple but effective strategy for identifying which words to focus on because those are the words that can significantly improve their comprehension across a variety of texts.

Storybooks. If you're going to use a storybook for an activity, go through it first and identify some words to teach your students—words they’ll need to know at some point. Their curriculum is also a great resource for finding vocabulary, and it doesn’t have to be limited to their language arts curriculum. Science, social studies, and math all contain many vocabulary words, not just the academic terms teachers focus on, but also those tier-two words that are essential for understanding.

In my district, the language arts curriculum changed every grading period, covering different topics. One period might include science, while another focused on fairy tales. For one science unit, they studied weather phenomena. "Phenomenon" is a word that I’m sure the teachers defined at the beginning, and it’s a word they used repeatedly—probably about 50 times a day. However, I would bet that many of my students still didn’t fully grasp its meaning by the end of the unit.

There were also plenty of other words related to topics like the impact of hurricanes, words they were expected to use in writing and discussion. But I’m not convinced they truly understood those words. It’s crucial to identify and teach these words explicitly, so students can confidently engage with the material.

When selecting vocabulary to teach, especially in cases like my high school student who struggled with nearly every other word in her textbook, it's important to prioritize. There are often too many words to cover, so focus on the ones that are most essential for understanding the passage. If you have an overwhelming number of unfamiliar words, choose those that are critical for comprehension.

Also, focus on words that can’t be easily inferred from context. Many textbooks or materials written for students will provide definitions for certain words within the next sentence. If the word is already defined in the text, you might not need to spend as much time on it. Instead, target words that are harder to figure out from context.

You may still want to briefly review the defined words, but when it comes to explicit vocabulary instruction, choose those that aren’t as easily deciphered. Additionally, limit the number of words you focus on at one time—about three to five is ideal. That’s a manageable amount for students to grasp and retain without becoming overwhelmed.

Let's Practice. Below is a passage that I use as part of my study. As you read it, pay attention to which words could be good tier-two words.

Gecko Found Living with Possum Family

"An Australian organization posted pictures of an unlikely scene. The scene was of a gecko cozied up to a family of possums. Staff and volunteers found them in possum nesting boxes. Nesting boxes are enclosures built by people to be a safe home. This is the first time anyone had seen a reptile with the possums. The next week, another volunteer saw the gecko was still there. “So it’s not just a one-off fluke,” he said. He guesses the gecko went to the nesting box for warmth. Geckos like to bask in the sun for warmth. They will not eat baby possums since they only eat insects. Possums will not eat geckos since they only eat pollen, nectar and insects. This is why they are able to live together."

Some tier-two words from the passage include gecko, pollen, reptile, basque, nectar, fluke, enclosure, and volunteer.

How to Teach Vocabulary

Once you’ve identified some words to teach, how should you go about teaching them? I’ve outlined four key approaches. First, we’re going to focus on explicit instruction, which is something I know I’ve been lacking in my practice. This type of instruction is also referred to as rich vocabulary instruction or robust vocabulary instruction, and we’ll dive into how to do this effectively.

Next, we’ll cover different methods for semantic mapping, which helps students visually organize and connect new vocabulary with related concepts. We’ll also explore morphological instruction, where students learn how to break down and understand word parts, like prefixes and suffixes, to enhance their word learning. Then finish with peer tutoring.

It's important to discuss how not to teach vocabulary. Don’t have students spend time looking up words in the dictionary. These days, most people don’t even use a dictionary—they just type the word into Google for a quick definition. So, don’t waste time with that, and avoid having students copy down words and definitions.

A couple of years ago, I was in a high school self-contained classroom where they were reading a story. The teacher gave the students a list of vocabulary words, and since the students weren’t strong readers or writers, he wrote the definitions on the board for them to copy down. They handed in their work, and that was called "vocabulary practice." I would bet my entire house that none of those students actually learned any of those words. Copying down words and definitions like that is just busy work. If students are making flashcards for later review, that’s different—but as a standalone activity, it’s a waste of time and does nothing to help them learn.

Explicit Instruction. Beck & McKeown defined explicit instruction as robust instruction, and there are three key components necessary to explicitly teach vocabulary.

First, you need a child-friendly definition. That complex definition of "lathe" we discussed earlier wasn’t even adult-friendly, let alone something a child could grasp. The definition should use words that the child already knows to help them understand the new term.

Second, you need to provide multiple examples in different contexts. This is how we begin building those semantic networks. If you use a word in at least two different ways, it prevents the child from getting stuck thinking that the word can only be used in one specific sentence or situation.

Finally—and this is crucial—the child must actively process the meaning of the word. You can have them say the word, which is important, but they also need to engage with it by identifying examples and non-examples, or by creating their own sentences using the word. When you ask them to do this, you often see that moment of realization—the look that says, "Oh, you’re asking me to do something with this word!" That’s when you know they’re starting to make connections. This active engagement is key for building a deeper understanding of the vocabulary.

Anita Archer, who I consider the queen of explicit instruction, has also spent time focusing on explicit vocabulary instruction (2012). Her approach is similar to what Beck & McKeown proposed but with a few additional elements.

First, you introduce the word and provide a student-friendly definition. Then, give at least two examples, and you can even incorporate pictures or drawings, which is especially helpful for visual learners. After that, have students make up sentences with the word.

The key step is ensuring that the child is processing the word. This is where checking for understanding comes in. Ask them questions that require deeper thinking and application of the word. For instance, if the target word is impact, you might ask a deep-processing question like, "How might a snowstorm impact school?" This encourages students to apply the word in a new context.

Next, you can ask something like, "Does studying impact your grades at school?" to help them think about the word's relevance in their lives. Finally, you might prompt them with sentence starters like, "Not sleeping well might impact your ability to..." and have them finish the sentence.

Archer emphasizes keeping this process quick and efficient. Kids don’t have long attention spans, so vocabulary instruction should move along briskly, with rapid-fire examples and non-examples. While you need to be mindful of your students' processing time, teaching a word should not take an hour—it should be a brief but effective part of the lesson.

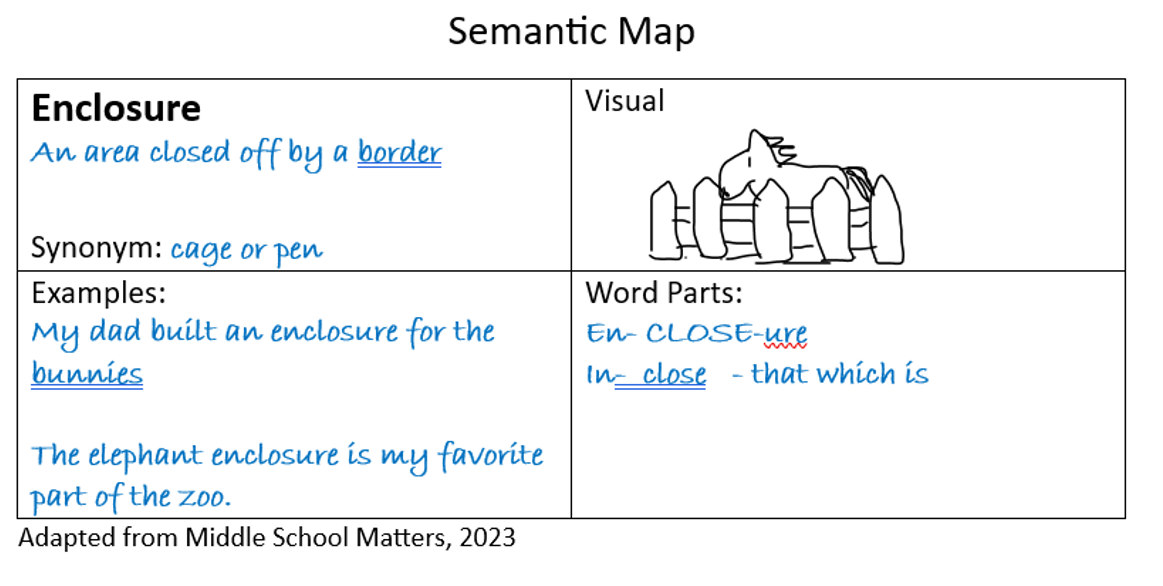

Example: Let me walk you through an example of teaching a vocabulary word explicitly using the word enclosure from a gecko passage. I did this for all the words I used in my study daily. While you may not want to spend this much time every day, it’s important to prepare some examples and processing questions in advance. What I want you to notice is how often I repeat the word and definition, and how many exposures the students get to both. This includes the number of times they say the word and definition themselves. All of these exposures count, as we know our students need lots of repetition.

So, if I’m going to teach this word, I would start like this:

"Okay, the first word today is enclosure. Enclosure. Can you say that with me? Enclosure. How many syllables are in that word? En-clos-ure. Say it with me: en-clos-ure. Three syllables. An enclosure is an area closed off by a barrier. What is an enclosure? An area closed off by a barrier."

Next, I would break down the word: "Our word enclosure has three syllables, and they all mean something. The root word is close. The en- at the beginning means in, and the -ure at the end means that which is. So, enclosure means 'that which is closed in.' That’s why it refers to something closed off by a barrier."

I would then ask again: "What’s the word? Enclosure. What’s an enclosure? An area closed off by a barrier."

Then, I’d provide examples: "My dad built an enclosure for the bunnies. He built a little area closed off by a barrier so the bunnies couldn’t get out. That was the enclosure. Another example is: The elephant enclosure is my favorite place at the zoo. The enclosure is the spot closed in by a fence so the elephants can’t get out."

I’d wrap up by reinforcing: "What’s the word? Enclosure. What is an enclosure? An area closed off by a barrier."

By doing this, students hear the word repeatedly, say it themselves, and connect it with meaningful examples, all of which help solidify their understanding.

In my study, I had the students write the word and the definition on the back of their papers. I’ll admit that it took a lot longer than expected, and I don’t think I would do it that way again. Maybe, instead, they could write a key part of the definition while I provide the rest. We also drew pictures together. I had them brainstorm with me about what kind of picture would represent the word, and if they didn’t have an idea, I’d suggest one and draw it while they copied. This added another modality to help them solidify the word.

Next, I’d move into some processing questions. For example, "An area surrounded by a fence is called an enclosure. Why would a baby’s playpen be an enclosure?" This is where the kids would pause and think, “Wait, what was enclosure again?” Then I’d prompt them: "Because the baby is closed in, with a little barrier to keep them safe."

I’d continue with another question: "Do wild animals live in enclosures? Think about it—if it’s an area closed off by a barrier, do wild animals live there?" This leads them to understand a non-example: wild animals are not in enclosures because they roam free.

Then I’d use a sentence starter: "The enclosure went around the..." They could fill in with anything: "the yard," "the bunnies." Finally, I’d reinforce the word and definition again: "What’s the word? Enclosure. What’s the definition? An area closed off by a barrier."

By repeating the word, offering various examples, asking processing questions, and using visual aids, I aimed to ensure the students really understood the word enclosure. This framework helped the students grasp and retain vocabulary throughout my study.

Semantic Mapping (Graham, 1985). Explicit instruction is the evidence-based practice we know helps kids learn vocabulary words. Semantic mapping is a tool that provides visual representations to support—not replace—explicit instruction. You can use word webs or word maps while you’re teaching the word, its definition, examples, non-examples, and engaging students with the word.

Semantic maps are helpful because they’re visual, which aids comprehension, and they help students access prior knowledge and understand relationships between words. This is where you can incorporate synonyms, antonyms, and categorizing. It’s important to note, though, that we’re not focusing on teaching synonyms and antonyms for their own sake. Instead, we’re teaching the target word, and through that process, we make connections to synonyms, antonyms, and similarities and differences.

When I used to teach similarities and differences, I would give examples like, “How are a bracelet and a ring alike?” thinking that this was teaching vocabulary. But the focus really needs to be on teaching the words themselves, and then, as part of that instruction, highlighting the synonyms, antonyms, categories, and similarities.

Here’s an example of how a word web might look: You can write your target word in the middle, include the student-friendly definition, and have the students repeat it. On the left, you can list a synonym, and on the right, an antonym. Add an example underneath, and if it’s helpful, you can include the part of speech and word parts at the bottom.

For the word enclosure, my word web would look like this:

- Definition: An area closed off by a barrier.

- Synonym: Cage or pen.

- Antonym: Open space.

- Example: Rabbit hutch.

- Part of Speech: Noun (a thing).

- Morphology: “en-” (in), “close” (closed), and “-ure” (that which is).

Semantic mapping is a great visual tool that works alongside explicit instruction to help students grasp and retain new vocabulary.

This is one way to approach explicit instruction, and you can incorporate visuals alongside it. As I mentioned, I also used flashcards. I had the students write the words and definitions, and then they used the flashcards to quiz each other.

Explicit Morphological Instruction. We discussed why morphology is important—understanding word parts helps students generalize their word knowledge and improves reading fluency. This approach is particularly beneficial for older students, as their texts tend to be more morphologically complex. However, don’t hesitate to introduce it to younger students. It can be seen as word play or word discovery, and even if they’re not fully engaged, they might start noticing how words are made up of smaller parts.

That said, explicit morphological instruction shouldn’t be the only focus. It can be incorporated as part of your overall vocabulary instruction. If the word you’re teaching includes a prefix or suffix, you can dedicate a day to morpheme-related activities or games. However, the primary focus should remain on teaching tier-two words, ensuring students can apply them effectively. You can still incorporate fun morpheme games—such as building multiple words using root words, prefixes, and suffixes—to reinforce the learning in a more engaging way.

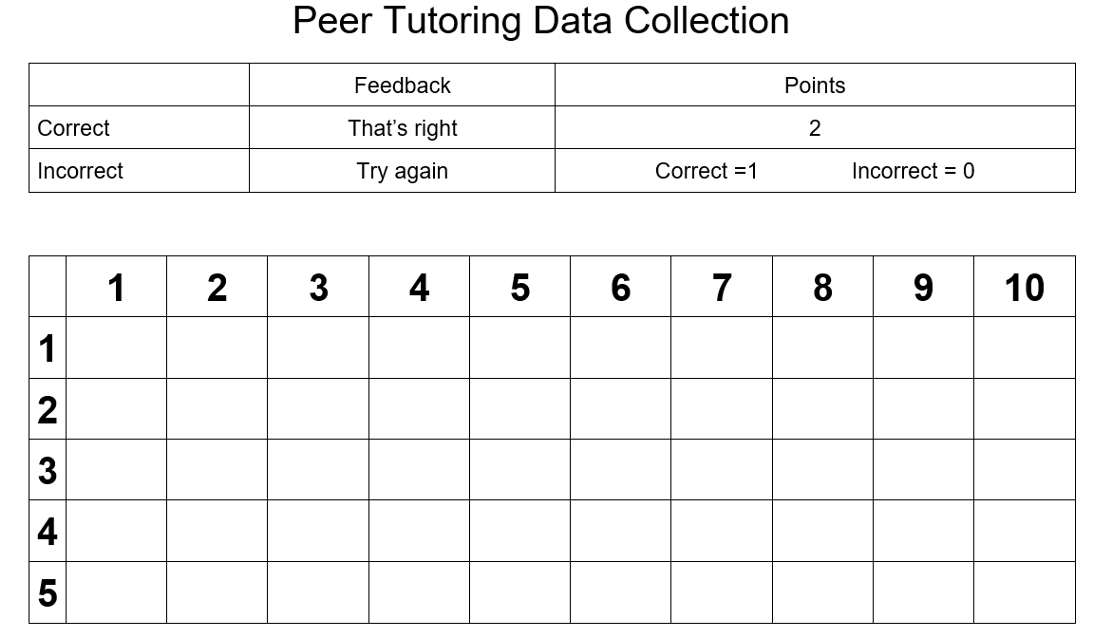

Peer Tutoring. As part of my doctoral studies, I worked on a project that involved an evidence-based practice called class-wide peer tutoring, which is something many teachers are already doing. In the younger grades, they often use the PALS program for reading, where kids work in pairs on letters and sounds. In this context, peer tutoring involves students quizzing each other on vocabulary words and definitions.

What’s great about this method is that it benefits both students. The student providing the definition reinforces their understanding by explaining the word, and the peer who is testing makes judgments about the accuracy of the response, which further strengthens their own knowledge. This peer interaction creates a valuable learning experience for both students.

Greenwood and colleagues devised some rules regarding peer tutoring:

- Student pairs are given a set of flashcards containing words that will be their targets for the day.

- The timer is set for 10 minutes. The first student will show the second student each card. The second student will define the word (or give the word if the definition is shown).

- After the second student responds, the first student will give feedback. “That is correct” or “Try again.”

- Points are awarded: 2 points if the second student got the definition correct on the first try. If they needed the cue, but then got it right, they get 1 point.

- When the timer goes off, the students switch roles of tutor and tutee for another 10 minutes.

- Total scores are kept for the class to see. The pair that gets the most points after a given amount of time gets a prize. Bonus points or prizes can also be given to students for giving each other good feedback. Additional prizes are earned for meeting pre-determined goals.

I’m not sure how many of you have the opportunity to do whole-class activities, but if you can, this would be a great option. Even in a small group session, it works well. If you have two students, they can pair up and quiz each other, or if you have four, you can divide them into teams and have them compete for points.

Here’s how it works: the students are given flashcards, which serve as their target words for the day. You can set a timer, but you don’t have to—it works either way. One student flashes the card, and the other student either gives the definition or says the word, depending on how you want to structure it.

The feedback is key. If the student gives the correct response, the first student says, “That’s correct,” and they earn two points. If the response is incorrect, the first student says, “Try again.” If the second attempt is correct, they earn one point. If they’re still incorrect, they get zero points, and the first student provides the correct answer.

You can continue this process, tallying up points as you go. You can organize it by teams, and if you want, offer small prizes for the team or student who gets the most points. This works especially well in whole-class peer tutoring setups, but can easily be adapted for smaller groups.

I made up this data sheet (see below) that is in your handouts. You can do it either going up and down if you're just doing five words, or maybe they do the words and the definitions, and so you'll get about ten responses.

You can use the data sheet however you’d like, but it includes a space to track the points. I’ve used this method not just for vocabulary but for other areas like grammar, specifically with irregular past tense verbs. I had a group of four kids who struggled with those verbs, so after teaching them the concepts, I had the kids quiz each other.

I’ve also used this approach for speech sounds, especially when students are working on discrimination skills. This method works well for a variety of targets—not just vocabulary—so you can adapt it to fit whatever goals you’re working on, whether it’s grammar, speech, or any other language skills.

Results of a Vocabulary Intervention Study

I wanted to briefly discuss my study, as I believe some interesting findings came out of it that I’d like to share with you. The title was The Effects of a Rich Vocabulary Intervention on Comprehension for Third Grade Students with Language Learning Disorders. I’ve already explained why I used the term "language learning disorders," and the focus of the study was on vocabulary to improve comprehension.

The Study

What I was really hoping to achieve was to improve students' comprehension by teaching them vocabulary words. The study used a single-subject design, specifically a repeated acquisition design, which isn’t very common, but I’m now fully on board with it and think it should be more widely used. For anyone interested in research, the study lasted eight weeks.

I conducted it over the summer, which may not have been ideal, but that’s how it worked out. The study included three weeks of baseline and five weeks of treatment. Each week, I pre-tested the students on vocabulary words and comprehension using passages like the gecko passage. During the baseline period, the vocabulary words were not from the passage, but during treatment, they were. At the end of each week, I conducted a post-test on both vocabulary and comprehension.

Then, the next week, I introduced a brand new set of words and passages. Essentially, it was like a pre-test/post-test design that I replicated eight times over the course of the study.

Participants

In this study, the students acted as their own controls. I also had a control group that didn’t receive the vocabulary intervention, but since it was conducted over the summer, it was challenging to keep the kids engaged. Unfortunately, I lost both students in the control group, but I was able to retain all three students in the treatment group.

All three students qualified for services under a specific learning disability. One student did not have any speech or language goals, another had only a vocabulary goal, which was interesting, and the third student was in a self-contained classroom with articulation and language goals. This third student had a significant phonological processing disorder at the beginning of the year—stopping, fronting, and deleting all final consonants, essentially showing multiple phonological processes. But things really clicked for him that year. By the time we did the study, the only speech sound he struggled with was with /r/, which was incredible progress. As we know, phonology and vocabulary are closely related, so his case was particularly interesting. He was almost a study on his own!

Variables

For the variables in my study, I implemented the rich vocabulary instruction just as I demonstrated with the word enclosure. I used words from modified passages, which I’ll explain in a moment. The passages came from an online news source called Newsela and were all set at a third-grade reading level.

When it came to testing vocabulary knowledge, I used two different methods. I didn’t rely solely on definitions because, as we know, our kids often struggle with verbal memory. I was concerned they wouldn’t be able to fully show what they had learned. So, in addition to asking for definitions, I included a receptive component called context test questions (CTQs). These involved asking five questions about the word in increasingly complex contexts, and the students would answer yes, no, or I don't know.

For the comprehension measure, I was particularly excited about using the Sentence Verification Technique (SVT). Measuring comprehension can be tricky—story retells are common, but I was worried about whether our kids could effectively retell stories and remember all the details. SVT provided a more receptive way to measure comprehension, where students only had to answer yes or no to questions. I’ll show an example of that in a moment.

For the gecko story, I had a rubric for the vocabulary definitions, including the specific words I expected them to know. I pretested the students, anticipating they wouldn’t know the words, and then post-tested them after teaching the vocabulary.

For the context test questions (CTQs), I’ll use enclosure as an example. The first question would be something very general, like "Did I use the word correctly in the sentence?" or "Was it the right part of speech?" For instance:

- "Can a man enclosure?" (Obviously, the answer is no.)

- "Can an enclosure be big?"

Students earned one point for a correct answer, zero points if they said I don't know, and minus one point for an incorrect answer. There were a total of five possible points for the context test questions and four points for the definitions.

The total score for the students’ semantic knowledge could reach a maximum of nine points. For the Sentence Verification Technique (SVT), I needed to modify the stories so they were 12 sentences long, which would generate 16 questions for the SVT task. All the students had to do was answer yes or no to each question.

The 16 questions were broken down as follows:

- Four sentences were verbatim from the story—exactly as they appeared. The question would be, "Was this sentence in the story?" The correct answer should have been yes.

- Four sentences were verbatim but with one key word changed. The correct answer here should have been no, since the sentence was altered.

- Four sentences were paraphrased from the story. The idea wasn’t to test memorization, but to check whether the meaning of the sentence matched something in the story. The correct answer should have been yes for these.

- Four sentences were distractors—completely unrelated to the story. The correct answer for these would be no.

That was the structure of the SVT measure, with the goal of assessing comprehension through a simple yes/no format.

Phases of the Study

So for the baseline, as I mentioned earlier, I did a pretest and post-test on the target words and comprehension. During this phase, I taught them vocabulary using words from picture books. Then, during the treatment phase, I continued with the pretest and post-test, but this time I focused on teaching five specific words.

I originally pretested seven words to account for the possibility that they might already know a couple. After identifying the ones they didn’t know, I narrowed it down to five words to teach explicitly.

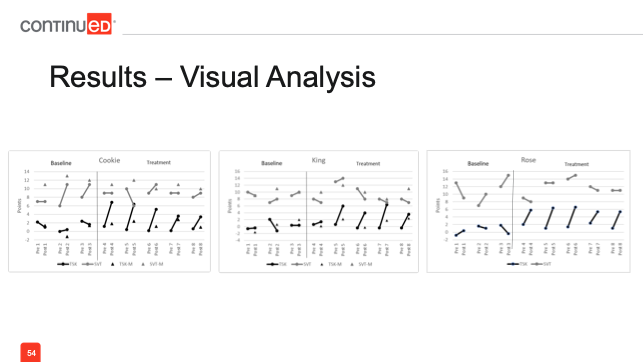

Results - Visual Analysis

Since this was a single-case design, we used visual analysis to interpret the data. The students in the study chose their own names—Cookie, King, and Rose. Let’s focus on the bottom of the graphs, where the black lines represent the comprehensive vocabulary scores.

(Click here for larger image of results.)

These charts show exactly what you’d expect in a repeated acquisition design. You can see the progression from pretest to post-test for each week. For example, week one started with the pretest, then moved to the post-test, followed by a brand-new set of words for the next week, repeating the cycle of pretest and post-test.

Once the treatment phase began, you’ll notice that the lines became more vertical. This indicates that the students didn’t know many of the words during the pretest, but we were hoping to see progress by the post-test, which is reflected in the vertical lines—showing improvement. This pattern held true for most of the students. King had one off day where he didn’t perform as well, and he also missed the first day of instruction that week, so he was taught separately, which might have affected his results.

The little triangles on the graphs represent the maintenance phase, which I conducted one month later. I retested the words to see how well the students retained their knowledge. While their scores weren’t as high during the maintenance phase, meaning they lost some of the word knowledge, they were still higher than their initial baseline scores, though not by a significant margin. This highlights the need for continued repetition and exposure to vocabulary.

The gray lines at the top represent the comprehension measures using the Sentence Verification Technique (SVT). Rose doesn’t have any triangles because she didn’t come back for the maintenance testing despite my efforts to contact the family multiple times.

For vocabulary, explicit instruction significantly improved word knowledge for all three students. However, as we saw, after the maintenance phase, without continued practice, they did lose some of that knowledge, although their scores remained higher than their baseline.

Regarding comprehension, there were no significant results. In fact, many of the students’ comprehension scores actually went down during the post-test phase of treatment, which is puzzling. We’ll discuss possible reasons for this in a moment.

Discussion of Results - Vocabulary

Let’s start by discussing vocabulary. The takeaway here is simple: kids learn words when you teach them. Even students with language learning disorders are capable of learning new vocabulary when it’s explicitly taught.

When I was practicing with the word enclosure, I counted each exposure as either me saying the word and its definition or the students repeating the word and definition. I saw the students twice a week. On the first day, I introduced the words and had them practice, and on the second day, we reviewed and practiced again. By practice, I mean they worked with flashcards. On average, each word received 111 exposures, which is why the students learned them. However, they clearly needed ongoing practice to retain the meanings over time.

There were no significant effects on comprehension, and I believe there are a couple of reasons for that. First, our students have language learning disorders, which means they need even more intensive work with words.

Second, I read the stories aloud to them. These were grade-level passages, and I read both the texts and the comprehension questions aloud because these students receive read-aloud accommodations in the classroom. For example, this could be similar to the read-aloud support they would get during state testing. However, if the students aren’t reading the passages themselves, we end up relying heavily on their verbal memory, which we know is an area of weakness for them. They also have reduced verbal attention, so they weren’t always fully engaged with the sentences being read to them.

Even during the SVT measure, I think some students would latch onto specific words they recognized. For instance, when I read a question, they might have thought, “Oh, wait, I’ve heard that word before,” without fully processing the entire context of the sentence. This could explain some of the puzzling results we saw.

Discussion of Results - Comprehension

Let’s talk about my comprehension measure, the Sentence Verification Technique (SVT). I was really excited about it initially, thinking it could revolutionize comprehension research. But it turned out to be much harder than I anticipated. As we know, comprehension involves more than just word knowledge.

There were likely sentence structures the students weren’t fully paying attention to, and they may not have had the necessary background knowledge to understand everything. For example, Cookie didn’t know what a gecko or opossum was, and those weren’t my target words. I had to explain those later, but by that time, he was already feeling bad about not knowing them, and I felt bad, too, for not realizing that earlier.

Another factor was verbal attention. I did the pretest and post-test within the same week, and I think the students were thinking, “We just did this!” They seemed to answer questions without fully engaging. Interestingly, during the maintenance testing a month later, they actually performed better than on both the pretest and post-test. I believe part of this was because it was the third time they had encountered the story, so the material felt novel again, giving them a fresh perspective.

Lastly, it’s possible that the words I targeted weren’t as critical to understanding the passage. However, I don’t think this played a major role since the passages were fairly short. Still, it’s something to consider when reflecting on the overall results.

Future Research

Research often leads to more research, and for anyone interested, there are many areas this study has opened up for further exploration. One thing I’d like to do is compare comprehension between typically developing peers and students with language learning disorders. As I mentioned earlier, there is empirical evidence that teaching vocabulary helps kids understand sentences containing those words. But in my study, that didn’t seem to be the case with my students. By comparing them to typically developing peers, I could determine whether there was something intrinsic in how I was teaching or testing that influenced the results.

I’m not ready to give up on the SVT comprehension measure, either. I’d like to continue working with it, perhaps by using passages that are more aligned with the students’ reading level instead of their grade level. This could help us see whether their comprehension improves when the material is more accessible.

Additionally, I want to explore different delivery models for vocabulary instruction. We know that distributed practice—spreading the learning over time—is more effective than mass practice. While I did spread the instruction over two days, it wasn’t truly distributed enough. What if we extended it over several weeks and then tested the students? That might lead to better retention.

Anecdotally, I noticed that words introduced during the baseline phase seemed to stick with the students. For example, the word temperament came up on our very first day. Later, in week five, while discussing a different topic, Rose suddenly recalled the word temperament in a new context, which was incredible. This showed me that using words repeatedly in different contexts really does help with recall, so perhaps the delivery model of the intervention could be adjusted to maximize those kinds of connections.

Key Takeaways

The key points I want you to remember are that vocabulary is a critical component of language and literacy development, and we need to spend more time focusing on it. It doesn’t have to take up your entire session; you could simply pause when a word comes up and teach it explicitly. Consider keeping a list of the words you’ve covered so you can revisit them later in different contexts or when the word comes up again.

We absolutely need to be teaching vocabulary explicitly, and I believe that student engagement is the area where we often fall short. We need to ensure that students are truly interacting with the words, not just passively hearing them.

Although my study's results didn’t show that vocabulary intervention directly improved comprehension, that doesn’t mean we should stop teaching vocabulary. In fact, the Matthew Effect shows that students with language learning disorders need more vocabulary instruction, not less.

I also think we need a better way to measure comprehension, which I plan to address when I redo the study soon.

Questions and Answers

How do you target vocabulary for students in low SES or even tier one words are unfamiliar?

If a word comes up that the students don’t know, it’s important to stop and teach it—that’s a must. I feel the same way when it comes to teaching concepts, like before, after, between, and around, which are mostly tier one words. There’s still value in explicitly teaching those concepts, but for other vocabulary words, teach them as they come up. For example, words like gecko and possum, which I assumed my students would know because the text was written for third graders, needed to be taught. I didn’t spend too much time on them—just explained that a gecko is a little lizard and showed a picture—but I focused more on explicitly teaching the targeted words from the text.

Here are two practical tips for implementing vocabulary instruction in a 30-minute session. Focus on teaching just three to five words. My sessions took a bit longer—around 45 to 50 minutes, as it was summer, and I had the students write the words on flashcards, define them, and draw pictures, which took too much time.

I recommend making the flashcards yourself and having the students verbally engage with the words instead. This should only take a few minutes. You could spend about three to five minutes per word, so that might be the focus of your lesson. Or, if you’re working with a storybook, you could pause briefly to teach the words, spending about two to three minutes on each, and then review them when they appear in the story to reinforce their meaning in context.

How do you get classroom teachers on board?

I haven’t had a lot of success with pushing into classrooms and working directly with teachers, but I know that those who have succeeded in this area find it much easier once the classroom teacher is on board and willing to collaborate with the SLP. Teachers would likely appreciate it if you offered to take over teaching some of the vocabulary, or you could present it as a service you can provide. You might also ask the teacher directly, “I want to work on vocabulary—this student has difficulty with it. Can you provide me with a list of vocabulary words or the texts you're using?” I think teachers like knowing they are being supported in this way.

In my school, I saw some teachers explicitly teaching vocabulary, which was wonderful to see, especially in kindergarten classrooms. Sometimes I’d walk in at just the right moment when the teacher needed help coming up with examples, and we ended up demonstrating words like agility to the whole class, which was a lot of fun. If you let the teachers know that you’re there to support them and ask for any materials they have—like newsletters with the week's vocabulary focus—you can work together to help reinforce those words in your sessions. Teachers usually appreciate knowing that their efforts are being supported, and this kind of collaboration can benefit both them and the students.

At what point should we really start focusing on tier-two?

You really should focus on tier-two words, and while working on them, you can incorporate activities like comparing similarities and differences. Of course, tier two words for a kindergartner will be different from those for an 8th grader, but the goal is the same—building vocabulary. Use words you come across in storybooks, classroom materials, or other sources, and concentrate on those tier-two words because students aren’t likely to pick them up on their own or even notice them when they’re used.

For example, if someone uses the word forbid, they may not pay attention to it or understand it. I remember one time when a mother kept telling her child to apologize, and the child just gave me a blank look. I realized he didn’t understand what apologize meant. The mom said, "He knows how to say sorry," and I replied, "Yes, but I don’t think he knows that apologize means the same as sorry." There are so many opportunities like that to teach tier-two words and build students’ comprehension and vocabulary skills. By doing this, you’re not only expanding their vocabulary but also improving their overall comprehension.

*See handout for a full list of references.

Citation

Harker, B.A. (2024). Vocabulary interventions for students with language disorders. SpeechPathology.com. Article 20694. Available at www.speechpathology.com