Editor’s Note: This text is a transcript of the course, Using Nonstandardized Assessment to Evaluate Cognitive-Communication Abilities in Students with Traumatic Brain Injury, presented by Jennifer Lundine, PhD, CCC-SLP, BC-ANCDS.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- List possible reasons for under-identification of students with traumatic brain injury (TBI) in the schools.

- Describe advantages and disadvantages of standardized testing as a means to assess youth with TBI.

- Describe appropriate nonstandardized assessment strategies that should be considered when assessing cognition and communication in this population of children and adolescents.

Types of Brain Injury

I am very happy to talk to you about nonstandardized assessment to evaluate children with brain injury in schools and also in outpatient clinics. To get started, I want to make sure we are all on the same page. Most of this course could very easily apply to any type of acquired brain injury, including both traumatic and nontraumatic injuries. However, some of the statistics on incidence and prevalence I will talk about at the beginning of the course deal specifically with TBI. This also includes concussion, or what is now being commonly referred to as “mild brain injury.”

“Other” (Non-traumatic) Brain Injuries

When we talk about non-traumatic brain injuries, that includes: infections like meningitis or encephalitis; brain tumors or tumor resections; anoxia, where the brain is deprived of oxygen; stroke; and other metabolic or chemical injuries to the brain.

Pediatric TBI: Facts and Statistics

Let’s discuss the incidence and prevalence of brain injury in our nation right now, and the most recent statistics from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). If we look at traumatic brain injury - for people who are presenting at least to an emergency department - we see that the three groups most at risk for TBI involve the pediatric population. There are about 700,000 children ages zero to 14 that are sustaining traumatic brain injuries every year. That is likely a low estimate of the number of actual injuries because again, we are only including children that report to an emergency department.

What happens to these children? We know that less than four percent of these children are actually admitted to an inpatient rehabilitation unit. There are some estimates that say about two and a half million students in our country’s educational system every year have sustained a traumatic brain injury at some point. Again, this particular statistic excludes all of those other types of brain injuries that have non-traumatic mechanisms.

These statistics are important because research shows that children who are not admitted to an inpatient rehabilitation unit are less likely than those who do go to inpatient rehab to receive ancillary services such as speech therapy after they leave the hospital. This may be because children who are admitted to an inpatient rehab unit have more severe injuries, or perhaps because inpatient rehab allows more time to educate families about the importance of follow-up. Service providers need to realize there is a huge majority of children who do not get admitted to an inpatient rehab unit and thus are at risk for cognitive-communication challenges, and are also less likely to receive services in the schools or in outpatient clinics. If there are two and a half million students every year in our schools that have sustained a traumatic brain injury, we are likely under-serving or under-identifying them 98-99% of the time. Very few of them are showing up as having a traumatic brain injury in our special education counts. By no means am I saying that every student who sustains a traumatic brain injury will require services, but certainly, it is likely more than one to two percent.

Why is there such a huge discrepancy? It is in part related to the fact that standardized testing often does not identify deficits in these children. Another part of the reason is that these children go back to school and they look okay; they are walking and they are talking and these later deficits become “invisible,” in a sense. Additionally, there is the challenge that deficits grow in later years in children who sustain a brain injury. Sandra Chapman (2006) coined the term “neurocognitive stall” to help describe this phenomenon. It refers to the fact that children who sustain a brain injury often regain the skills that they had prior to their injury, but later on, they have trouble keeping up with developmental milestones due to the injuries to the brain that impacted their memory centers and later-emerging cognitive skills.

The primary problems that these children deal with after a brain injury, particularly as related to speech-language pathology, are cognitive-communication challenges. These are challenges that present as communication problems but that really arise from issues in cognitive domains such as attention, memory, self-awareness, organization and problem solving.

Picture a child sitting in a classroom who is asked to write an essay comparing the habitat of a forest to that of a desert. If this child has trouble with attention, the essay may be really challenging and she may be unable to complete the task due to being unable to sustain her attention. She may be really distracted, and may lose focus within or between paragraphs and forget what she is talking about. If this student has poor memory, she may forget that one of the assignment requirements is to incorporate key vocabulary that has been discussed in class; or even if she does remember that requirement, she may not remember the key vocabulary itself. Memory impairments may also cause difficulty keeping track of what she has already written, and she might repeat herself. If this student struggles with organization, the essay could lack coherence and cohesion; i.e., it could lack flow, and ideas may not link together from beginning to end. Again, the difficulties with this essay may make it look as if the student has issues with written language, when in fact, the deficits are due to underlying cognitive problems.

Cognitive-Communication Challenges Post-TBI

Cognitive-communication challenges are a very big issue for these children. With students in the classroom, cognition challenges may often be misattributed to attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or even behavioral problems. These children are walking and talking, and not easily identified as having a communication impairment, but the child's social participation can be impacted very significantly. He might appear socially awkward, or have trouble initiating or maintaining conversations. The child may have trouble with disinhibition and impulsivity, and say things he should not say. He may be emotionally labile, get very upset very quickly, or cry or act out in inappropriate ways, and this causes trouble maintaining or acquiring friendships.

Additionally, cognitive-communication challenges can lead to significant impacts on later psychosocial and vocational outcomes. Research studies have found that individuals who experience a TBI during childhood or adolescence have fewer close friendships than individuals who have not sustained an injury. These individuals with TBI are less likely to enroll in secondary education, and are less likely to live independently and obtain a paying job. A very significant problem is that these individuals are also at increased risk for offending behavior and incarceration.

Outcomes: Delayed Developmental Consequences

We know that brain injury jeopardizes the ability to master new skills, as we have already discussed. We know that there are specific areas of the brain, such as the frontal lobes, that are slow to mature, so we may see difficulties in frontal lobe functioning much later, when that part of the brain is expected to “come online.” Oftentimes, we see increasing emotional and behavioral problems in these children as time goes on.

Unfortunately, we still do not have a great system of care to help deal with the chronic challenges of pediatric brain injury. Schools are where children are spending the majority of their time outside of the home, yet we are underserving them there. We know that if we can interact with these students and deal with these challenges earlier and more proactively, we are better able to obtain good outcomes for them.

Progressive Difficulties Increasing Risks of Long-Term Failure

Typical difficulties seen in students with acquired brain injury include trouble following complex verbal and written directions, and trouble incorporating new vocabulary or new information into something that they previously learned. They have trouble learning new information, and difficulty paying attention in higher-level, complex ways. They may also have difficulty managing their lives overall, primarily due to frontal lobe or executive function impairments. We know that when these children start to fail at school, they tend to disengage, and they also display more behavioral problems that become barriers to achieving success in the classroom.

I want to reiterate the estimate that we are missing a huge percentage of children in our educational systems, and/or not appropriately identifying them as brain injured. When we do not identify these children in the first place, or misattribute the difficulties that they are having, they may not receive services at all or might be served under an inappropriate special education category that misses the cause of those problems. Behavior problems are a glaring example of this issue; behavior problems that occur after a TBI are usually dealt with in a different way than are “normal” behavioral challenge. We can see, then, why these children begin to struggle in the classroom, and why they have trouble maintaining friendships or trouble with peers. This can lead to behavior problems because they do not feel good about being in school.

How do we begin to change this situation? I would propose that our challenge is to improve our ability to identify the cognitive-communication difficulties experienced by students with TBI through appropriate assessment. If we can properly assess them to better identify the subtle deficits that they are experiencing, we can provide appropriate services for them to remediate and rehabilitate some of the challenges that we have talked about.

Standardized Assessment

First, let's talk about standardized assessment. Standardized assessment does have some advantages as well as some disadvantages, and I want to discuss those before we talk about nonstandardized assessment today. I do not want to say that standardized assessment does not have a place in our evaluations for children with brain injuries, but I will have to admit that I did have a hard time coming up with some of its advantages.

Advantages of Standardized Assessment

In general, as speech pathologists, we understand what standardized tests allow us to do, because we are trained to use them in graduate school and we rely on them very heavily for our assessments. Standardized assessments allow us to compare a child's performance to the performance of similarly aged peers. Usually, though, that is a peer group with typical development, and that may not be the best comparison group because it often does not include any children with traumatic brain injury. But at least using standardized assessment allows us to see how the performance of a child in front of us compared to a similarly aged group.

We also have a reference - typically the standard deviation from the mean - that allows us to “score” the student’s performance. That magical one and a half to two standard deviations below the mean might allow a child to qualify for services in a particular school district, for example.

Another advantage of standardized testing is that with these assessment tools, the methods are structured and prescriptive. This is helpful when you are a busy professional with a large caseload. I do not say that mockingly at all because we all understand how difficult it is. We will talk about the challenges with nonstandardized assessment in a little bit as well, but one realistic and perfectly fair reason to default to standardized tests is because they are familiar to us and readily available in our cabinet.

Disadvantages of Standardized Assessment

Ecological validity is a major challenge when looking at standardized assessment, especially with children with traumatic brain injury. As a reminder, ecological validity is the idea that the findings of an assessment can be generalized to a real-life setting; in other words, is what we are assessing on a standardized test similar to what a child would encounter in everyday life? Standardized tests are designed to assess a child's ability to demonstrate a specific skill, but they are not designed to predict success or failure in a real-world context, particularly when we are talking about cognitive-communication abilities. An SLP might consider giving an articulation test to a student who is struggling with speech, and we would expect the errors identified on that articulation test to be consistent with the child's errors in a non-testing situation. When it comes to cognitive-communication skills, however, we do not see that as much. Standardized assessments typically are not targeting the skills and abilities that students with TBI need to use in their everyday activities.

In addition, these tests do not often assess the common areas of deficit that students with TBI experience; that is, cognitive-communication deficits. There are very few standardized or criterion-referenced tests available that look specifically at cognitive-communication skills in students with TBI. In a few minutes, I will talk about some that do exist.

Let's discuss why these standardized tests do a poor job of assessing skills needed for real-life activities. First, think about the testing environment. Speech-language pathologists and neuropsychologists typically conduct testing in a quiet, one-on-one environment where the child has plenty of time to respond. There are few to no distractions, and the examiner is there to help redirect attention every time the child gets off track. Anyone who has been in elementary or middle school classrooms knows that this is NOT what a real classroom is like. In a real classroom, students are expected to take tests or work on projects with the doors open to the hallway, where lockers are slamming and children are talking. The windows might be open, fans might be running, there may be other people working around the students or children who are blowing their noses. All these things are happening, and that student with a brain injury is expected to maintain his attention on a task just like every other typically developing child in the room. But all those things, which might be distracting for any child, make it that much harder for a child who has trouble with attention, organization or memory due to brain injury. In a quiet testing environment, these children may do just fine, but their test performance may not reflect what their actual performance in a normal classroom looks like.

Along similar lines, standardized tests often collect only small samples of many behaviors, and they have fewer cognitive demands; therefore - especially in a supportive environment like a one-to-one testing situation – these tests may not stress the child in any given area to the point where those functional weaknesses are revealed. They just do not place the cognitive demands that are typical of the challenging classroom environment. For example, a student who struggles to create and adhere to a timeline for a major class project might do very well with a simple scheduling task on a criterion-referenced test, where the parameters are known and they are not subject to the day-to-day challenges that children face in their everyday lives.

These standardized tests often look at what we should do rather than what we would do. For example, they look at specific patterns of reasoning, whereas real-life situations require students to use their own judgment and their own scaffolding. There was an interesting study looking at adolescents with traumatic brain injury, who were able to respond appropriately on a social pragmatics test when asked, “What would you say to someone who recently lost a loved one?” They were able to do that appropriately, but in real life, these same students struggled to respond appropriately in situations that were similar. Again, the test looked more at what children should do, but not at how they actually function in everyday life.

In addition, many of our standardized tests look at the knowledge that the student had prior to her brain injury. This is especially true when we are talking about developmental tests of language, which tend to focus predominantly on form and content. If the student had a grasp of age-appropriate syntax and vocabulary prior to experiencing a brain injury, then unless she experienced specific damage directly to the language areas of the brain, those skills and abilities are likely to come back once she has passed through that post-injury period of immediate recovery. In reality, the issues that we see do not tend to be with form and content of language. The primary deficit in cognitive-communication disorders is actually with language use, and not with syntax, morphology, phonology or even vocabulary; those latter areas tend to be generally intact after the initial recovery from a brain injury.

Standardized Tests for Children with TBI

There is very limited availability of standardized tests geared specifically to school-aged children with traumatic brain injury. Two examples that do exist are the Pediatric Tests of Brain Injuryä (PTBI) and the Student version of the Functional Assessment of Verbal Reasoning and Executive Strategies (S-FAVRES). These assessments are designed for adolescents or young people who have experienced an acquired brain injury. The PTBI covers children ages 6-16; the S-FAVRES is for children ages 12-19, so it is focused more on adolescents.

All of this sums up what we should think about when we consider standardized assessment for children with traumatic brain injury. Again, there are few standardized assessments geared specifically toward these children. In addition, our typical developmental language tests do not include children with TBI in their norming samples, which makes it a challenge to compare those norms with the results of the children with TBI that we see.

Nonstandardized Assessment

I will focus the rest of our time on nonstandardized assessment. It is important to say up front that nonstandardized assessment does not mean I am recommending people do informal or a “free-for-all” type of assessment. When nonstandardized assessment is done well, it does require systematic clinical procedures. It does require rigorous attention to detail. We need to be looking at these students in different contexts. So, I just wanted to qualify that initial comment and emphasize that nonstandardized assessment does not mean we are doing something non-evidence-based or with no clinical insight into other assessment procedures. It is also important to note that the ASHA Practice Portal does designate nonstandardized assessment as a crucial component of a comprehensive evaluation for individuals with pediatric traumatic brain injury.

Advantages of Nonstandardized Assessment

What are the positives of using nonstandardized assessment for students with traumatic brain injury? We talked about the inability of standardized assessments to evaluate performance in a realistic, everyday setting or activity as a disadvantage of those types of tests. Nonstandardized assessment, on the other hand, allows us to do that.

One example is watching a student take notes during a classroom lecture. What is that student doing? What is he writing in his notes? Is he able to pay attention? Another example would be observing students socializing with peers in the lunchroom. How are they interacting? Are their comments appropriate? Are they initiating conversation, or they sitting there quietly and taking things in? We can also observe students as they are preparing to go home from school. You might ask, “What does that have to do with speech-language pathology or cognitive-communication?” But I would argue that this is a very important time. Is that student grabbing the appropriate materials they need to complete their homework assignments, and/or any necessary textbooks or folders that need to go home? Is she grabbing her planner, where homework assignments have been carefully written down? Another example is looking at how the student responds to a prompt or instructions about a written essay. How does that student respond to that type of a prompt, and what does her written essay look like? We can also observe a student during group time in the classroom. If the science teacher turns the class over to allow students to work on a group project, what is this student doing? Is he able to stay on task? Is he contributing to the group or just sitting there lost because he is not exactly sure where to go?

An additional advantage of nonstandardized assessment is that it can inform the development of intervention plans. This is, as you may recall, another disadvantage of standardized testing; often those tests do not give us a clear starting point for immediately beginning intervention. I want to consider an example as we talk about this a little bit further. If you have a student who has a below-average score on a standardized test of memory, that gives you very little information about how those memory difficulties may or may not affect that student's performance in the classroom. We know their score on a memory assessment, but what does that actually look like for that student in the classroom? In contrast, if we use a nonstandardized assessment format, we can see where the student actually breaks down during everyday academic tasks. We can figure out what factors might be impairing her ability to participate in a specific curricular assignment. Is the student able to identify main ideas? Is she able to recall relevant details to be included in an essay, for example, or to answer a question appropriately in class? Is she able to persist in a specific task when given free time to work? Is she able to organize that assignment and determine next steps? These perspectives directly line up with intervention planning; identifying that a student is breaking down in any of those areas gives us an immediate place to start our intervention plan. These perspectives also happen to be consistent with the World Health Organization's (WHO) focus on activities and participation, instead of impairment level.

Another advantage of nonstandardized assessment is that in at least one study that compared neuropsychological testing of some of these cognitive domains in adults with TBI to nonstandardized assessment, nonstandardized assessment was actually more predictive of how well these individuals did in later work. Again, this should not be very surprising, because nonstandardized assessment allows us to identify real-life activities an individual is struggling with, as compared to standardized testing, which limits that ability.

Disadvantages of Nonstandardized Assessment

I do not want to gloss over these disadvantages, because they are important challenges for busy individuals with large clinical caseloads to consider. There is absolutely the potential for higher clinical burden on an SLP. Yes, the observation can be time-consuming. It is more challenging to document everything when you are doing nonstandardized observation, than when you are simply asking standardized test questions and filling out the test form. Our results need to be reliable and valid, so we do have to do this observation in a systematic way; we cannot do it quickly and without thought. Our observations do have to target the specific areas of concern where we feel like the student is struggling, and we have to figure out how to observe those areas in an everyday situation. These are certainly challenges for SLPs. I would argue, however, that once you are comfortable with the different areas that can be assessed in nonstandardized assessment, these disadvantages do not have to persist. It is something that gets easier over time as you become more and more comfortable with nonstandardized assessment.

Another disadvantage of nonstandardized assessment is that there is not a manual or a test form on which we can rely. We do have to think outside of the box to figure out what environments we need to observe these students in, and what specific activities we need to observe.

I do not have a bullet for this in the slides, but we should discuss an additional disadvantage as well. When using nonstandardized assessment, we do not have that simple norm-referenced comparison that is available for standardized tests. We have to figure out how to qualify a student for services based on these nonstandardized assessments.

Examples of Nonstandardized Assessment Methods

There are several different types of nonstandardized assessment. We are going to focus most of our time today talking about curriculum-based assessment and discourse analysis. We will also talk a little bit about task analysis and dynamic assessment, which we can use as a part of those other two types of nonstandardized assessment.

Curriculum-based assessment (CBA). We need to consider that children in literate, more developed societies are spending more time in the classroom than perhaps any other environment. Therefore, the classroom does happen to be one of the most ecologically valid places where we can observe a child's cognitive-communication abilities. This is a crucial environment for children because they need to be successful here in order to go on to the next phase of their lives, whether that is middle school, high school, secondary or post-secondary school, or specific vocational training. I also want to note that we are talking a lot about school as a context today; this is important because children spend so much time in that environment, and it is also the most likely place for them to encounter speech pathology services. I also want to stress, though, that these same points apply to speech-language pathologists that work in outpatient clinical settings. Individuals who work in those settings can still work on these same types of ideas; they just have to be a bit more creative about the types of situations they set up for observation of the client, in order to make the activities relevant for the child's life. We want to focus on curriculum-based or school-based activities even for students that are seen in an outpatient clinic.

Curriculum-based assessment is essentially using the school curriculum and its content, and also the context where that content is provided, to measure both a student’s intervention needs and his or her progress on the established intervention plan. Again, I want to reinforce that curriculum-based assessment is not just informally observing a child's behavior. It is carefully and systematically using data to evaluate a student's cognitive-communication abilities in that important context. It may require staging certain situations or contexts in the classroom so that you can see where the student’s areas of weakness are, or you may be taking an identified weakness and observing what kinds of modifications to that situation might be beneficial.

During curriculum-based assessment, we need to identify when and where a breakdown is happening during a particular activity. Is the student able to maintain attention initially, but then starts to break down after a certain amount of time or with environmental distractions? Or is he never able to even get started on a specific task? Curriculum-based assessment allows us the opportunity to trial different strategies or skills so we can plan intervention appropriately. We will talk about some examples in the case studies coming up.

We can also identify whether or not an intervention or strategy or skill is helpful in changing a student's behavior or his performance in the classroom or another relevant environment, such as the lunch room. That is how we will be monitoring and measuring success. Rather than getting to a specific score on an assessment tool, we want to see observable behavioral change in a student's classroom performance.

Questions relevant to CBA. There are some questions that are important to ask as we initiate a curriculum-based assessment. These questions come from Nickola Nelson (1989), who was specifically talking about language interventions, but they are relevant as well to cognitive-communication impairments that students with traumatic brain injury experience. First, we need to identify the skills that are needed to complete the activity or task we have identified as important to the student, or with which the student may be struggling. We also need to think about the cognitive-communication skills and strategies the student is demonstrating. In other words, where does that student have weaknesses, and what do they need to improve upon in order to complete this task successfully? Then we can figure out what modifications we might be able to make to the curriculum, to the classroom environment, or to expectations, that might make the student more successful in completing this task.

Modifications. What modifications might we consider if we are doing curriculum-based assessment? I am going to go back to two of those other types of nonstandardized assessment I mentioned very briefly. Task analysis is probably familiar to all of us, but just as a review, this refers to breaking down an activity into its component parts. When completing a task analysis, we think about the different steps that are required for a student to finish a given activity successfully. We have to then think further about what skills or abilities are needed to complete each individual step. We may figure out that a student is able to complete the first few steps independently, but breaks down at a later step in the process.

Dynamic assessment is also something that most of us are probably familiar with, but in this specific context, we can use dynamic assessment during a curriculum-based assessment to identify or introduce strategies, skills, or modifications to a student's specific work in a specific task, and then observe how those change the student's performance. Does the strategy or modification help her complete the task more successfully, or not? If so, we may add this strategy to our intervention plan and work on it with this student either in class, or in very structured pull-out sessions prior to adding it back to push-in types of intervention.

CBA example 1: Juan. Let's look at a case example of curriculum-based assessment. Juan is a seventh grader who sustained a moderate traumatic brain injury one year ago. Juan has average language scores, but shows mild delays in memory and executive functions on neuropsychological testing. Teachers and others at school are starting to see Juan exhibit some challenges. He tends to be off task, he shows disruptive behaviors when his teachers are lecturing, and he is suddenly scoring low grades on assignments and tests related specifically to lecture materials.

Curriculum-based assessment might help to identify some of the problems Juan is having in these specific tasks. We know from neuropsychological testing that Juan has issues with memory and executive functions. He has decreased attention, poor organization, poor working memory, and also some disinhibition. It is easy to see why these TBI-related symptoms might result in the problems we are seeing in the classroom.

We begin a curriculum-based assessment with Juan. We want to watch him as he is sitting in a classroom when a lecture is taking place, because this seems to be a particularly challenging environment for him. First, though, we think about what is necessary for a person to be able to take notes during a lecture. The student has to listen and comprehend the material, and he has to be able to identify the main ideas and the primary details and write those down. He also has to be able to inhibit less relevant details; i.e., he needs to not write down details that are not very important to remember. The student also has to be able to shift his attention; he has to pay attention to the teacher who is talking, but also write things down.

As part of your dynamic assessment, you provide a skeleton outline to Juan, and this helps to reduce the demands on his attention and his working memory, and also helps him to inhibit those irrelevant facts from popping into his notes. You might also ask the teacher to move his seat to the front of the classroom; this allows him closer access to the teacher to improve his sustained attention to her when she is talking, and it may cut down on some of those distractions he was experiencing previously when he was closer to the door or the window.

Lo and behold, we see that Juan demonstrates some great improvements with these strategies and modifications. The skeleton outlines and a new seating chart improve his ability to record the appropriate details during lectures. He writes better notes, and now he is able to study from those good notes, which hopefully will improve his scores on assignments and tests. He has shown a reduction in distracting or off-topic behaviors because now he is appropriately busy during class, and the teacher is right in front of him and can even tap on his desk when it appears his attention is waning.

CBA example 2: Malik. I want to talk about a case example of a younger child as well. Malik is a kindergartener who experienced a severe traumatic brain injury four years ago when he was about one year old, well before entering school. Unfortunately, this case study is based on one of my former patients who experienced all of the problems that we will talk about. When Malik was discharged from inpatient rehabilitation, his language and cognitive skills were within age-appropriate limits, and he received no services after being discharged from the hospital. Now that he is in kindergarten, he has begun to exhibit numerous difficulties. He is not able to rotate through center time in the classroom, he shows lots of disruptive behaviors, and he is really struggling with pre-literacy skills. We are now in the middle to end of his kindergarten year, and his parents have just been informed that Malik is failing kindergarten. The school was actually unaware of his TBI history up to this point.

One of the possible TBI-related symptoms that Malik is experiencing is poor cognitive flexibility. Even though we do not expect a lot of cognitive flexibility from a kindergartener, Malik is not even able to exhibit the flexibility we would expect for a typically developing kindergartener. He also is apparently struggling with memory and new learning, and he clearly has a low frustration tolerance as well.

We implement some dynamic assessment with Malik, and start to track his behaviors, their contexts, and the consequences of those behaviors in collaboration with the school psychologist. We notice that lack of structure and increased noise during station times appear to be overstimulating and distracting for him. We also note that when he has unplanned schedule changes, he demonstrates a big increase in his negative behaviors. We see that he has a really hard time paying attention to his teacher, especially during group activities like carpet time or stations.

As part of our curriculum-based assessment, we try using headphones to screen out additional noise and improve his attention during stations. This is very helpful for Malik because he does not have to work so hard to pay attention. The teacher implements a personal frequency modulation (FM) system, which improves Malik's direct attention to her when she is talking during structured learning activities. We also implement a picture schedule for the entire classroom. This allows the entire class to know what is coming. For any student that struggles with flexibility, this is going to be helpful; even though we cannot predict every single thing that is coming, there are many things that we can predict. If there are special activities on a given day that are not part of the usual routine, we can let the children know about this ahead of time by using the picture schedule.

Discourse analysis. Discourse analysis is the second type of nonstandardized assessment that we will put special emphasis on today. Discourse analysis can be an essential part of evaluating students with TBI because the discourse that students are required to use in school is much more sophisticated, and a student’s discourse abilities will be dependent upon the specific areas impacted by a traumatic brain injury. Discourse is not something that is assessed on most developmental tests of language, though the Test of Narrative Language (TNL-2) is one exception. Discourse analysis allows us to look at how a student is interpreting or expressing complex ideas in speech or in writing.

When looking at the discourse of students as they are progressing through school, we need to consider all modalities (reading, writing, speaking, listening) and compare those to grade-level expectations. We also need to consider all discourse genres, such as conversation, narrative, informational or expository, and persuasive.

Discourse analysis: relevant variables. When we are doing discourse analysis with students, there are several things we can analyze. We can look at lexical diversity, or how much they vary their vocabulary and whether they are using vocabulary specific to a lesson in science class or history class, for example. We can look at syntactic complexity, or how the students are combining clauses within sentences and using different types of sentences in their verbal and written language. We can look at content and structure; in other words, is the content sufficient, is it relevant, and is it organized well enough to meet the purpose of the verbal or the written passage? In addition, is the language appropriate for the intended audience?

Summarizing as a means of assessing discourse comprehension. We can also use discourse analysis as a means of looking at comprehension of language, not just expression. I think this is very important as well. I am particularly inclined to think about summarizing in these types of contexts because summarizing allows us to see how well a student is able to grasp the main idea of a passage, put that together with past information, include key details, and also implement appropriate organizational structure. All of these areas are quite vulnerable to the effects of brain injury. We can make sure that a student is comprehending sentence-level vocabulary, if he is able to ascertain the theme or argument of a passage, and whether he is able to identify relevant details.

Discourse analysis: methods. How do we elicit a discourse sample from students, and what exactly are we going to analyze? Again, I have a personal preference to use a summarization task as opposed to story-retelling paradigms or spontaneously-generated discourse samples because I think summaries are more ecologically valid with respect to the work we expect students to do in the classroom. In the classroom, we do not ask students to retell exactly what they read in a textbook or exactly what they heard the teacher say. We ask students to integrate these points with points that they may have heard yesterday, and to grasp the main idea on their own. I think this is an important consideration to think about as we are eliciting discourse samples from our students. Additionally, when we ask a student to retell us something, we are providing the necessary vocabulary and structure and details within our stimulus. In a summarizing task, in contrast, we are asking the student to do those things for himself, and thus it allows us to really see where he might break down.

It is also important to remember that these tasks are going to look different depending on the grade level of the student. We need to be comparing our tasks and results to grade level expectations. If your school or district uses Common Core, look at what is expected for that grade level; that is what we would be using to help determine if a child is on track or not.

Discourse analysis example: Maria. Let’s look quickly at Maria as a discourse analysis case example. Maria experienced a moderate to severe TBI three months ago. She has average language and average to low average memory and executive functioning on neuropsychological testing. But in school she is starting to show poor grades and incomplete assignments, and is spending excessive time doing homework, which is very frustrating to her family. Some of the problems she is experiencing may be related to frontal lobe executive functioning deficits, such as planning, organization and working memory impairments. It is also important to note that Maria is in her first year of high school, and these teachers are new to Maria, so they perhaps do not recognize that these issues represent a change in her behavior.

Using curriculum-based assessment over multiple days and in multiple classrooms, you are able to do some discourse analysis work with her, and you examine a report that she submitted in history class. It is disorganized, there is no central theme, and it does not follow the length requirements for the project.

As an intervention plan, we would try to assist Maria with planning and organizing these longer-term assignments. How does she determine the steps needed to finish this type of a project? We need to help her understand how to record appropriate due dates, and establish a method of indicating when things are completed and turned in. As for the discourse itself, you can teach Maria to use graphic organizers and outlining to streamline the structure of her discourse.

Maria starts to experience success with these tasks after the curriculum-based assessment. Once these strategies have been taught, she may just need some very brief check-ins to monitor how she is progressing with all of this on her own.

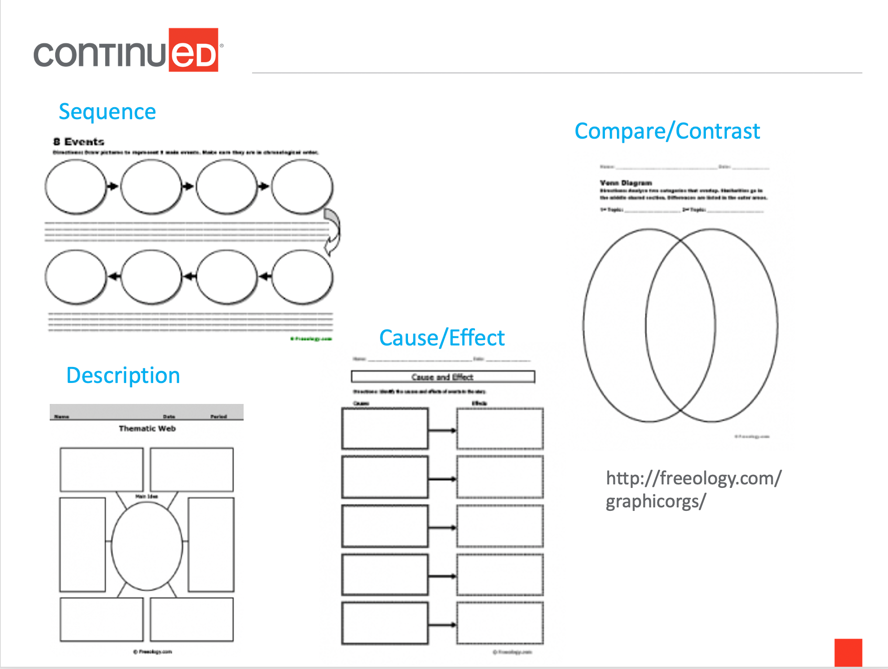

Graphic organizers (Figure 1) are a great way to help students structure verbal or written discourse. These are very simple examples, but students in higher grade levels can use these types of organizers as well.

Figure 1. Graphic organizer examples.

Implications for Success/Summary

What we know about nonstandardized assessment is that if we can improve the success of students with TBI in school, we can reduce all of the additional challenges that we talked about earlier. Students are less likely to have behavioral challenges, they are more likely to have better peer relationships, and their long-term outcomes for both school and later employment will be improved.

Questions and Answers

What has your experience been with other parties - whether it be school administrators, classroom teachers, or third-party payers - accepting these nonstandardized assessments? It seems like it is going to entail a lot of advocacy and education on our part.

You are absolutely right. I can speak to Ohio specifically, and I can say that in our requirements for qualifying children for special education, nonstandardized assessment is included in the methods that professionals can use to qualify children for services. I think it is used less often than it should be, though. We need to get this message out so that not just researchers, but also educators and people who work in the schools are pushing this method to administrators. This method of assessment is going to give us better information. I do joke about being afraid that this will increase people's caseloads substantially because I am certain that there are a lot of children in schools that are not identified right now, that would be identified if we could evaluate everyone using nonstandardized assessment. Obviously, that is another challenge. But in order to serve these children appropriately, this is what we need to be doing. I think we just need to start pushing the envelope a little bit and doing this. As our caseloads grow, I am hoping we can then hire more speech pathologists in schools.

Some of the information that we talked about in the ASHA Practice Portal might be used as evidence to bolster our case when speaking to some of those other parties.

That is right, and certainly, from a research perspective, there is important work we need to be doing to demonstrate that this is a way to better serve these children.

How do we identify these children? Because in schools, we may not even know that they had a traumatic brain injury.

That is a very valid point. The first thing we can do is ask. I think that we need to add questions to our kindergarten screenings about whether or not students have experienced any kind of brain injury, even concussions, in the past. We do not have a great understanding of how these injuries might impact students if they occurred before the children entered school. But these are certainly questions we can ask, especially if we see a student that is exhibiting some of the difficulties we have spoken about today. Sure, the issues could be due to ADHD. But we can, and should, ask these children or their families, “Did you ever go to the hospital because you hit your head?” That would be one way to start to better identify these children.

How might we informally assess a high schooler post-concussion or mild TBI in an outpatient setting?

I think trying to mimic classroom work is what we should be doing in outpatient clinics, not relying on workbook activities. We need to figure out what this student is struggling with in school, so it is a good idea to contact the school to ask. The student might not qualify for services in school, and it might be the outpatient SLP that will provide these services. Even though, I would argue, school services may be justifiable from an academic perspective, it may just be that the school is not able to qualify this student. But we need to find out what this student is struggling with in school.

Concussion can be a little bit of a different case, especially if this high schooler is either demonstrating persistent issues, or has just recently sustained the concussion. I am happy to talk about that offline, or to direct you to two papers that just came out in the American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology (AJSLP) that talk about the CDC's guidelines for mild brain injury and how they relate to speech pathologists. There is one article that focuses on young students and one that focuses on middle and high schoolers, so those may be helpful for you. You can also email me for more information.

Citation

Lundine, J. (2020). Using Nonstandardized Assessment to Evaluate Cognitive-Communication Abilities in Students with Traumatic Brain Injury. SpeechPathology.com, Article 20382. Retrieved from www.speechpathology.com