Editor’s Note: This text is a transcript of the course, The Spaced Retrieval Technique: A How-To for SLPs, presented by Megan L. Malone, MA, CCC-SLP.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Describe the spaced retrieval technique and the evidence to support its use with patients with cognitive impairment.

- Provide two examples of goals that could be addressed using the spaced retrieval technique in speech therapy.

- Describe the process of how spaced retrieval is implemented to improve functional recall of information

Thanks for joining me for "The Spaced Retrieval Technique: A How-To for SLPs." This is one of my favorite therapy methods to discuss, and I'm so happy that you want more about it, and how you can apply spaced retrieval to your patients and to your practice. I'm going to give you some examples and an overview of spaced retrieval training, discuss the evidence behind it, and share some applicable case studies using the technique.

I have used spaced retrieval training for over 20 years with a number of different clients. It's a technique that is easily implemented. It's effective for improving recall. I use it for both in-person and for teletherapy clients. I have my students at the university use it frequently with their clients and even have them use it on themselves to help with retaining information a little better.

As I'm discussing spaced retrieval training, I think you will find that you have that been using a form of this methodology already, but just weren't aware of what it was called or didn’t know some of the research behind it. If that's the case, this is going to be great validation for what you've already been doing to help your patients improve their recall.

If this is new to you, then I think you'll find that spaced retrieval training is something that makes sense, has strong evidence to support its use, and can be implemented immediately after this course.

Acknowledgments

I would not be here without the wonderful work and support of a lot of different people and organizations: The Menorah Park Center for Senior Living/the Myers Research Institute in Beachwood, Ohio. This is where I first learned about spaced retrieval and was involved in a number of federal grants and privately funded grants that looked at implementing spaced retrieval. I wouldn't be here without that great experience.

Some other organizations that assisted in studying the spaced retrieval technique included the State of New York, the Department of Aging; Hearthstone Alzheimer's Care in Massachusetts; Northern Speech Services; the National Institute on Aging, and the Retirement Research Foundation.

What is Spaced Retrieval Training?

I'm going to give you a quick overview of what spaced retrieval actually is before we get into the nuts and bolts of how it works. Spaced retrieval training (SRT) is a technique that's used to help persons with cognitive impairments recall important information over progressively longer intervals of time. It's called spaced retrieval because it is the idea of progressively longer intervals of time to recall information; spacing out the retrieval of information.

This technique was actually first used to work on face-name learning with non-impaired individuals; in the UK in the late 1970s. This might be a new technique to you, but it's actually something that's been studied for quite a long time. It was applied initially with non-impaired individuals and was found to be a useful way for people to retain information and retain the name of a person in a picture.

In the mid to late 1980s, it started to be applied to rehabilitation. Some of the grants and populations that looked at using spaced retrieval training with different populations included: patients with Alzheimer's disease, traumatic brain injury, Parkinson's, dementia related to HIV. So, spaced retrieval has been studied for quite a bit of time and has been looked at with a number of different populations that we see in different settings. Studies have also shown that spaced retrieval training can be successfully used with aphasic patients to improve naming skills and to teach compensatory eating and swallowing strategies. You can see that spaced retrieval can be applied pretty much to any patient that you might be seeing. We just have to be creative about how we think about its application.

It's an effective tool that therapists can use to help clients reach their goals in rehab therapy. It's also something that can be billable and reimbursable. It's recognized by ASHA as an evidence-based practice for persons with mild to severe cognitive-communication impairments. Additionally, it takes advantage of the procedural memory system and is success-based.

Let’s move on to how memory works and the underpinnings of how this particular methodology works. As I do that, I'm going to focus on dementia; not because this is the only population or diagnosis that you can use spaced retrieval with, but because obviously, we know with dementia and Alzheimer's disease, we see memory being severely impaired as the progression of the diagnosis goes on. Therefore, I want to use this as our framework because we know we have memory impairment associated with dementia. However, memory impairment is also associated with a number of other disorders or diseases. I want to review how memory works and how SRT would actually be applied to dementia. If we can see how it works with dementia, we can then see how SRT might map onto other populations we might work with.

Dementia Review

As we know, dementia is not a specific disease. It's a descriptive term for a collection of symptoms that can be caused by a number of different disorders that affect the brain. Alzheimer's disease accounts for 60-80% of cases. Vascular dementia, which occurs after a stroke, is the second most common dementia type. A lot of the early research was focused on using spaced retrieval with dementia. Then we saw the overflow of research into other populations after it was found to be successful with persons who were diagnosed with dementia.

The research also tells us that dementia is the loss of mental functions involving memory, thinking, reasoning and language to the extent that interferes with a person's daily living. Those symptoms can include things like language disturbances, challenging behaviors, asking the same question over and over again, maybe wandering, difficulties with ADLs, difficulty sequencing to dress or do personal grooming, or even personality changes. We might see people really disengaged, trouble initiating, or maybe aggressive behaviors. So, a number of these symptoms might pop up.

Again, dementia is an umbrella term, not all of these symptoms have to be present. If we start to see any of these things happening with our patients or loved ones, then we know that it is really affecting the person's day-to-day life, and that warrants us to refer them for further evaluation with their physician to determine if dementia might be in play.

Memory

Thinking about memory and cognitive impairment, it’s important to know how memory works in general. Memory is dependent on organizing incoming information. It requires attention and highly developed encoding skills. That would be step one. If we want any of our patients to be able to recall information or retain it, they have to be able to attend to it and encode it in a way that is meaningful to them so that it can be stored in long-term memory.

Memory is not only critical for remembering things that happen in our lives, but also for acquiring language, developing higher-level thinking, and making decisions. So, when we see people with cognitive impairment or memory impairment, we have to remember that it's not just those day-to-day moments that are impacted. It is also affecting their ability to communicate and to make decisions.

Memory Stages

Memory can operate in stages. That encoding process is taking something and making it meaningful. This could happen when you're thinking about studying for an exam, taking notes, using pneumonics to visualize or connect particular information to something that makes sense to you. Then you're going to store it and retrieve it. All of these things are interactive processes.

The ability of one process affects the quality of another one. If we have really good encoding for information, if we can try to remember something better, that's going to affect our ability to retrieve it later on. So, these stages are interdependent and we want to look at each of the stages when we're helping our patients remember things better.

A deficit in one stage can lead to a deficit in another. We need those skills to support one another and therefore we may need to focus on those deficits in treatment to assist with those stages and those abilities in order to see recall and retention get better.

Memory Definitions

Working Memory/Short-term Memory. This is the ability to use information as it's being processed. Remembering a phone number is a good example. We might rehearse that information, put it in our phones, and then it's gone. We really didn't need to tie any meaning to it because it wasn't something we were necessarily going to need for later. We see working memory and short-term memory being primarily affected first with Alzheimer's or other dementias.

Long-term Memory. This is information from short-term memory that's retained permanently. It consists of declarative and procedural memory. Procedural memory is relatively-spared through the progression of dementia. So, keep that in mind. That doesn't mean that it's not impaired at all, but research has shown that procedural memory can be used with patients who might not have a progressive memory impairment that goes with Alzheimer's disease. Procedural memory is important for spaced retrieval and is really the foundation for that technique.

Long-term memory can be affected by dementia in both storing information and retrieving it. Again, that doesn't mean it isn't affected at all, it’s just less affected.

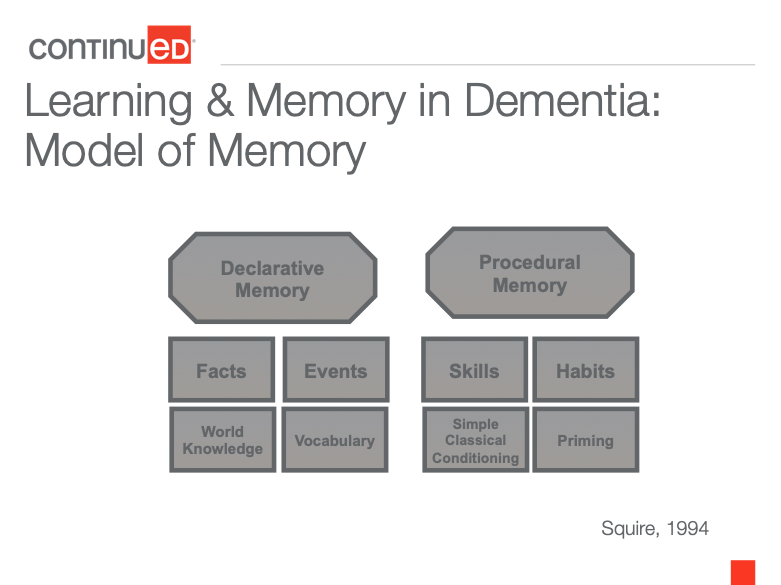

This is a model of long-term memory that I use really frequently with my patients and families to help them understand how long-term memory works and why we might see some splintered skills in persons with dementia.

Figure 1. Learning and memory in dementia: model of memory.

We might have patients and families say to us, "I don't understand why my mom can't remember my name, but she knows how to read, or she can sit down and play the piano." I'm sure you've all seen some of the wonderful videos online of patients who may not remember what they did a few minutes ago, but when they listened to a piece of music that they love, they can sing along to the lyrics or can start to play the song.

Different circumstances can tap into that procedural memory and this model helps to clarify why some strengths are present and why some weaknesses are present. Dr. Larry Squire created this model in 1994. The idea is that declarative memory and procedural memory make up the long-term memory system.

The declarative memory is that running timeline of what's happened in our lives; who we are, who's in our family, what we do each day, etc. It’s that storage for things like facts and events. Declarative memory is also where we store information like vocabulary. It’s our ability to know what something is called, express something, or understand what people are saying. It’s our knowledge of the world such as knowing that Paris is the capital of France or knowing the name of our first elementary school. These are things we have stored away.

With declarative memory, especially for persons with dementia, those are the trickier things to remember. They might have difficulty remembering the names of their family members, what they did earlier in the day, the name of an item or object, or basic world knowledge ideas. Those might be trickier things for persons with dementia to recall. But we have also seen that sometimes they can recall those things. If, for example, I give them some cues then they're able to remember (e.g., "Your daughter's name starts with an M.” “Oh, yes, it's Mary.”) Again, it doesn't mean that this information can’t be accessed, it just means it's a little more difficult to access it.

I always think of information in declarative memory as files in a file cabinet where the drawer is a little bit stuck. You have to give it a bit of a yank. You have to give some cues in order for that information to be recalled. It's kind of accessible, but it's something that we're seeing deteriorate over time in terms of our patients who have progressive memory impairment being able to access that information.

On the other hand, the procedural memory system, which is part of long-term memory, has been found to be relatively spared through the course of dementia. Again, it doesn't mean that it's completely free and clear, but over time it is less impaired. Our memory for procedures is exactly what it says it is. It’s our memory for skills and habits, how to do things we've done repeatedly throughout our life such as tie our shoes, feed ourselves, read, if that was something that we learned early on. It even includes things like driving. Unconsciously, being able to drive home after work if you've had a hard day, you might not consciously remember being on the road or all the turns you made, but somehow you end up in your driveway. That's because you've done that route so many times, you can almost do it in your sleep. That's procedural memory. It’s something that we've done so many times that it becomes very automatic.

Other things that are stored in procedural memory include the idea of repetition priming. Priming is the idea of practice makes perfect. The more exposures we have to a piece of information or doing something, the better we're able to retain it or do it.

Finally, there is simple classical conditioning. If you remember back to Psych 101, this is the idea of a certain stimulus eliciting a certain response. That is really going to factor in when we talk about spaced retrieval because it involves a prompt or a question; something that can elicit a certain response from somebody with enough practice. That also includes priming.

Procedural memory is something that we can use and capitalize on. Spaced retrieval is really based on the idea that this part of memory is relatively preserved. We capitalize on it, not only through priming and classical conditioning but also by using some of those skills or habits that are retained. This is why many times when we are working with persons with dementia, we see recommendations for including external memory aids, reading a cue, having something written down. Because reading is a skill or habit that has been practiced so many times throughout life, it becomes relatively automatic. Therefore, it's something that we can use to help our patients remember things better.

Again, I use this model quite a bit when I'm talking to my patients and families about why their skills might be a bit splintered. “Why can't they remember my name?” Well, that would be something more under declarative memory, which we see deteriorating a bit more. “But why can I remember how to read or to play the piano?” Well, that's a skill or habit that you've practiced over and over. It's something that has been kind of cemented into long-term memory a little better and you have better access to it.

A family member might ask, “Why can't they remember where their room is, but they can locate their seat in the dining room?” Well, they're probably going to that dining room multiple times a day for activities and meals and so forth. Maybe they're only going to their room once at the end of the day after they get up. They have more repetition, more priming to the idea of going to their seat in the dining room, more practice with that and so it is a little easier.

This example also illustrates that persons with dementia can learn new information. They've never learned to live in a facility setting before, but somehow, they know exactly where their seat is in the dining room. That's something they didn't know beforehand, and they're probably in the facility because they have a cognitive impairment possibly. So, that’s a great illustration to staff about how new learning can happen with this population.

Mistaken Beliefs about Dementia

This leads to the idea of mistaken beliefs about dementia. A lot of times we might be dealing with family, staff, or patients who've been diagnosed and think that they can't learn or remember anything anymore. They believe the best way to care for persons with dementia is to make them comfortable, accept their idiosyncrasies, and be patient. But the truth of the matter is, persons can still learn new things. It's just about how it's presented, how it's taught, and how it is practiced.

We are talking about this with dementia, but we could apply it to a lot of other populations who might be experiencing memory impairment or needing a way to retain new information better. Again, memory is memory across all populations. We're just talking about how it might be impaired differently based on different diagnoses.

Circumvent the Deficits

Our goal in working with any of our patients is to circumvent the deficits. All of our patients, whether they have dementia or something else, may have weaknesses. That's probably why they're coming to see us. We might see weaknesses in areas of learning and memory. But a lot of people have a lot of other strengths. And it's important to think of things from a strength-based perspective and look at what abilities are there. We know what difficulties people are having, but what strengths do they have.

When we're talking about persons with dementia, they do have the ability to learn procedures and the ability to read. Those are things that have been shown to be preserved through the procedural memory system. So, let's take advantage of that.

Research has shown that the learning of information and its retention depends heavily on how it's presented. It's all about making something meaningful and how regularly it is practiced in order to learn and retain it. We want to be aware of the weaknesses, but we want to focus on the strengths, and keeping that in mind for all of our patients is really important.

Behavioral Interventions for Dementia

Behavioral interventions for dementia, or any intervention method, can be a direct or an indirect method. Spaced retrieval training can be both. A direct intervention is when an SLP or another professional intervenes directly with individuals or a group using an intervention. When we use spaced retrieval or some other technique with an individual or a group, that is a direct intervention.

Indirect intervention is when an SLP or another professional trains caregivers in an intervention, modifies the environment, or develops activities to maximize function. As I said, spaced retrieval can be both direct and indirect. We can use this directly in our sessions with patients, and we can train caregivers to do it.

We can make environmental adaptations to help support skills such as using written cues and we can come up with activities that might maximize function. So, spaced retrieval falls under both categories.

Spaced Retrieval Technique

Hopefully, you have a better understanding of exactly why spaced retrieval might work, how memory works, and are motivated to see it in action.

Goal of Using SRT

The goal is to enable individuals to remember information for long periods. We're not talking about a couple of seconds or a couple of minutes. However, when we're teaching and training someone to remember a new piece of information, we are starting at those smaller time intervals. But we really want to see retention for information for days, weeks, months, or even years so that a person can achieve long-term treatment goals. This will vary based on the different diagnoses a person has, the progressive nature of the diagnosis, etc. But there is good research showing that long-term retention of information can occur.

Therapists can teach clients strategies that compensate for memory impairments, using the procedural memory system, including reading and repetition priming. We can improve patient safety. We can teach swallowing strategies, precautions, and recall of meaningful information like family members' names or orientation information.

We can even teach patients how to complete daily functions such as taking medications, paying bills, attending appointments, etc. You might think to yourself, “Oh yeah, I have a lot of patients who are working on sticking to a medication schedule.” There are a lot of great tools available now that have alarms or buzz when the person needs to take their pills. Unfortunately, I have found that many of my patients have those tools but when the alarm goes off, they're not sure what it's for. SRT can be used to help with that. “When you hear this sound, what does that mean?” “Oh, it means I take my pills.” A client may say, “I need to know when my next appointment is, where do I go to look for that?” Then we can have some procedure built into that, “Where do we keep the calendar? Well, how do we check it?”

In addition, spaced retrieval can use external aids to compensate for memory. An external aid is just a fancy word for having something written down and being able to refer to it. External aids can really help to externally store information which is pivotal for persons who have memory impairment because retention can be difficult. If something is stored externally, meaning outside of their own memory, they're going to have a better chance of accessing it and remembering it. Again, all of this can be supported with the patient’s ability to read. If someone hasn't learned how to read or has some other impairments that might make that difficult, we can find ways around it.

I've used spaced retrieval to help people press a button on a recordable picture frame for a message. If they can't press a button due to a physical impairment, how can we get around that? Can we think of some other ways that they can retain information? We want to think about the strengths and know what the weaknesses are. But we're going to circumvent those so that we can focus on the positives and the abilities people do have.

What Does SRT Look Like

We're going to begin with a prompt question for a target behavior and teach the client to recall the correct answer. That’s that simple classical conditioning idea of stimulus-response-question-answer.

When retrieval is successful to that question, then the interval proceeding the next recall trial is increased. So, we're going to wait a little bit and ask the question again a few seconds later to allow for repetition. If they get it correct, then we're going to keep increasing the time.

If, at any point, the person has difficulty recalling the information, they are told the correct response and asked to repeat it. This follows the idea of errorless learning which is the minimization of error responses during the presentation of target stimuli. Basically, if a person can't answer the question correctly, you're going to provide the correct answer, ask the question again, and have them repeat the correct answer.

You might think, "Okay, great. When my patients have a difficult time remembering something, I usually do give them the answer." But the key with spaced retrieval and why it's success-oriented is because it includes errorless learning. When the person has difficulty recalling the information, we give them the correct answer immediately, ask the question again, and then allow them to repeat it. This gives them another repetition of the correct information; another way to prime their memory for retaining that information. Following those simple steps of repeating the correct answer, asking the question again, and having them repeat the answer can make a huge difference in retaining the information. It's allowing that priming to occur.

If they miss the answer, you're going to go back to the last time interval where they were successful. The length of the recall intervals can vary and usually, we'll see people kind of double time. Meaning, if we allow 10 seconds between intervals and they get it correct, then maybe wait 20 seconds and ask again, then 40 seconds, and then 80 seconds. So, you are doubling the time. They're inching out the amount of time that they're retaining the information a little longer.

It’s a type of shaping paradigm that's applied to memory. You are pushing out the window of time bit by bit for the person to remember the information. Each time they get it right, you add a little more time. Anytime they get it incorrect, you provide the correct response, ask the question again, have them repeat that response, and then go back to the prior interval where they last demonstrated success.

You can use a timer or an app to track intervals. There are many different ways to track the time so that you can track progress with your patients and attain goals.

Treatment: Spaced Retrieval

Let’s consider this goal, “Client will independently recall the location of their daily schedule to complete ADL's, improve attendance at and participation in meals, and engage with peers 90% of trials.” The prompt question for spaced retrieval with this particular issue is, “Where should you look to find your daily schedule?” The answer we want from the patient is, “Look at my walker.” You can see in the picture that the daily schedule is attached to the person's walker. So, we want them to look at that to remember where they need to be each day.

Figure 2. Picture of walker with patient’s schedule attached.

How would this look for spaced retrieval? I might start off by saying to the client, “Today, we're going to work on helping you get through your day a little easier. I have our schedule here and I've attached it to your walker.” I'm going to make sure that they can read it, that the print is big enough, that they can reach it, etc. We want to make sure that all of those things are in place before we start training them to remember to use it.

Then I might say, “Every time we practice remembering this, I'm going to ask you the same question. It might get a little repetitive but that’s only to help you remember it.” I always tell people that I'm going to ask them this a lot. You will have patients who will say, "Oh my gosh, please don't ask me that question anymore." But that's okay, that's the point. Just explain to them that it's going to happen a lot, and then you'll get that uncomfortableness out of the way.

So, I might say, “Okay, we're going to remember to use our schedule. I'm going to say, ‘Where should you look to find your daily schedule?’ And I want you to tell me, ‘I look at my walker.’ So, let's try it.

“Where should you look to find your daily schedule?” Patient says, "Look at my walker." So, at zero seconds, meaning immediate recall, I gave them the question, gave them the answer, asked them the question, they answered correctly. So, they got it right. I'm going to reward the correct response with a little bit of time.

Now I'm going to wait 10 seconds. I'm going to ask the question again. At 10 seconds, I say, "Where should you look to find your daily schedule?" Patient answers, "Look at my walker." I may have them touch the schedule or read something on it just to make sure they can use it. I may say, “Hey, you're doing great. This is great. We're going to keep on practicing here today.”

Then I wait about 30 seconds. I might set my timer, I could use an app, I could use the second hand on my watch, whatever it might be. Again, I’m just waiting a little longer. I ask the exact same question again, “Where should you look to find your daily schedule?” And the answer, “Look at my walker,” is given by the patient. It is very key to use the same wording of the question and the same answer each time as the response.

Again, we're looking for stimulus-response; taking advantage of classical conditioning. If we change up the wording at all, it's going to change that effortless retrieval that we're looking for. That could force us into that declarative memory system where we know that file cabinet door is a little stuck. So, you really want to think about keeping your wording consistent for both the question and the answer. It’s a good idea to have it written down, so we're using the same question and the answer each time.

In this case, the patient got it right at 30 seconds. So, I waited a little longer, rewarded it with more time, and waited a minute. In that minute, I may set up some of the other therapy tasks we're going to do. We might talk about the weather or walk to the patient's dining room table. Then, I ask the question again with the same exact wording, “Where should you look to find your daily schedule?” And maybe the patient says, “Uh, I can't quite remember." You can almost see that effortful retrieval. They're really trying to access memory that they can't get to. We want to avoid that.

When we start to see them hesitate or give a partial answer, we immediately jump in and say, "Actually, you look at your walker." Then we ask that question again, “Where should you look to find your daily schedule?” And they say, "Look at my walker." That's the errorless learning piece. If they miss the answer, we give it to them, ask the question again, and have them respond. Then we return to the last interval where they demonstrated success. In this case, it was at 30 seconds. They missed it at one minute, so I go back to where they were last successful. We're rewarding them and giving them credit for the time they were able to retain the information. But we're giving them another opportunity to repeat it with that immediate recall, that errorless learning piece. Then we go back to 30 seconds and ask the question again. If they get it right, then I move up to one minute after that. In this case, the patient responded correctly at one minute, so I continue the session.

You can continue to add time or reduce time based on whether or not the patient is answering the question correctly or incorrectly. I'm going to have them use the schedule and try to answer some questions, “What time do you go to breakfast?” Or “Tell me what you do after you brush your teeth.” I want them to really use the strategy that I'm giving them. We all know actions speak louder than words, so we want to make sure that they're actually using the strategy that we're giving them.

As those intervals get longer, you can be doing other tasks. You might have other goals that you're working on with this client that you can fold into the spaced retrieval training for the other tasks you're working on. Then just intermittently stop and ask the question, see if they respond correctly, write down your time and then have them use the schedule and add or decrease time accordingly. It really is something that's very easy to implement. It's just based on correct or incorrect responses and increasing or decreasing time.

Now we're going to try it. I want you to try to remember what my name is through the rest of the course. We are just using a simple question, “What is my name?” The response that I'd like you to give, silently to yourself, is “Megan”.

Let's say we're working together and you're a new client of mine. I might say to you, “If we're going to be seeing a lot of each other, why don't we practice remembering my name?" I might take off my name tag or anything like that because I want true retention. I don't want them to read my name tag, unless I'm trying to train them to read name tags, which can be a very effective way to work with patients, especially in facility settings; but that is not the goal.

So, you are my new patient and we're going to practice. “I'm going to ask you a lot of this question today, but just remember, it's going to help you to remember it a little better. Whenever I say, ‘What is my name?’ I'd like you to say, ‘Megan.’ ” “What is my name?” “Megan.” I'm going to click that you got it correct and now my timer is starting. It's counting down from 15 seconds. We're going to wait about 15 seconds and then I'm going to ask the exact same question again and hope for the same answer from my patient. When the timer goes off, I ask, “What is my name?” The answer is, “Megan.”

Now I'm increasing to 30 seconds. You don't just sit and wait silently, you can talk in between with your patients. You can look at what's on their schedule for the day, you can talk about how they've been, you can look at some pictures. You don't have to just stare at each other.

But the important thing to remember is that you don't want to be actively discussing what the person's trying to recall. You want to make sure that those intervals are pretty clean. Meaning, you don't want to be talking all about how my name is Megan in between these intervals. I might say, "Great, we'll keep on practicing. Let's look at our schedule today." Then, when my timer goes off, I'm going to go ask, “What is my name?” And hopefully, they respond with “Megan”. Then we move up to 1 minute. So, as I move along in the course, I will keep doing the training of learning my name.

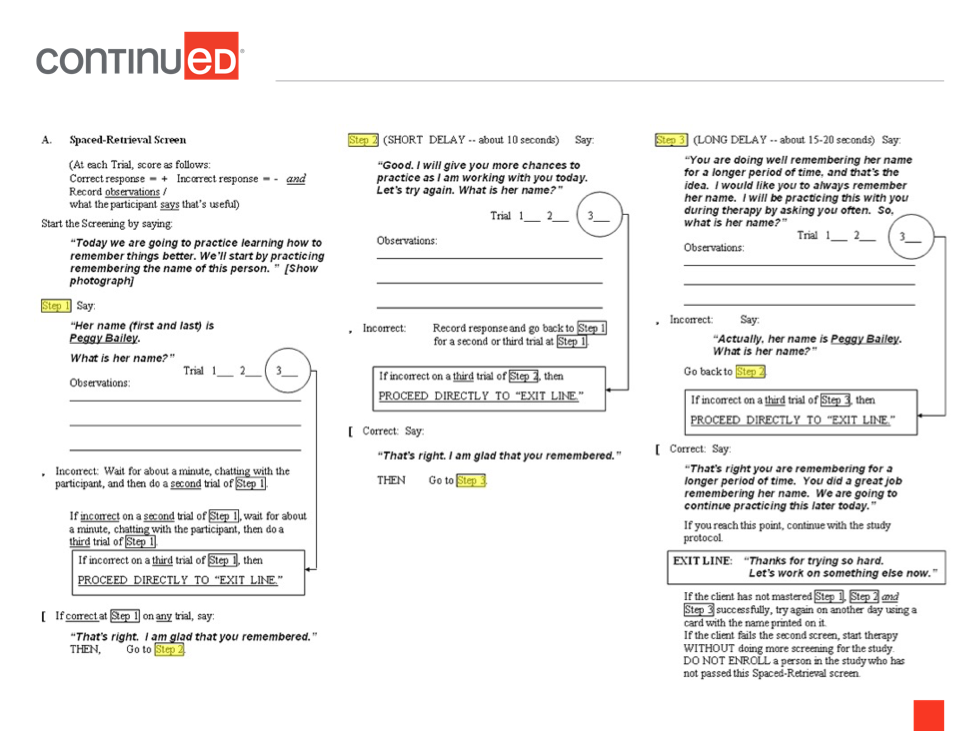

SR Screening Measure

There is a very simple screening measure available to determine who is an appropriate candidate for spaced retrieval. It tests a client's ability to respond correctly to the given piece of information over three different time intervals: immediate recall, 10 seconds later, and 15-20 seconds after that. It's basically a mini-spaced retrieval session. You're going to try to teach somebody the name of a person. I usually use a picture to do that. Then I give them the name and ask them the question. That’s the immediate recall interval. Then, I ask 10 seconds later, and then 15-20 seconds after that. If the patient is able to do that, then they're showing that they're able to use this technique effectively.

(My timer just went off, so I'm going to ask, “What is my name?” Hopefully, you said, “Megan”. Now, I am going to extend the time to 2 minutes. We went from one minute to two minutes so we're doubling the time. Again, you don't always have to double time. If a person is missing the answer because you are doubling, you can do something in between. If they regularly miss it at the two-minute interval, maybe go to a minute and a half before you ask again. You can play with the time. You're not locked into one particular set of time.)

The spaced retrieval screen can be easily folded into any evaluation. I typically do this with most of my patients, especially if they have cognitive issues, to see if SRT is something I might be able to use in therapy.

Here is an example of using the screener for a research study that we did when I first started out. We were using an anonymous person in a picture and the patients were asked to remember the name, Peggy Bailey.

Figure 3. Spaced retrieval screener.

We started out by saying, “We're going to practice learning how to remember things better. We'll start by practicing the name of the person in this picture and the name is Peggy Bailey.” If the person's able to say, "Oh, her name is Peggy Bailey," after you give them that particular response, you wait a short delay of about 10 seconds. Then you say, “Good. I'm going to give you more chances to practice as we're working together today. What is her name?” If the patient gets it correct at trial two, then we're going to extend the time they have to remember it.

About 15-20 seconds later, we ask the question, “What is her name?” If they respond with "Peggy Bailey" as they're looking at the picture, then they've shown that they can learn new information in this manner. That's all you need to do for the screener. However, let's say we get up to the long delay and I say, “What is her name,” and the patient can't remember or starts to show some effortful recall and they are trying to remember but they just can't do it, then I'm going to give them the correct answer. “Actually, her name is Peggy Bailey.” I repeat the question, “What is her name,” and the patient says, "Peggy Bailey." Then I move back to the last time interval where they demonstrated success, which was 10 seconds. I wait 10 seconds, ask the question again, and then move up to the long delay.

In the above example (figure 3), each step has three different trials. So, the patient has three chances to go back and forth and remember the information. You could do this with Peggy Bailey, you could do it with your own name. You can find easy stock pictures online to use. There are many different ways to do this simple screening. It's been shown that even patients who have Mini-Mental State Exam scores below a six have been able to pass the spaced retrieval screen. That's fairly low when you think about a lot of these cognitive screenings. If a patient is dealing with that level of impairment and is able to pass this type of screen, then it’s worth giving to see if it's something that might work in therapy.

SR Goals: Prompt Question/Answer Examples

If a patient passes the screen and they've shown to be a viable candidate for using this technique, we can work on many different goals with them. Some examples of prompt questions and answers are listed below, but in no way are you limited to this list. You're only limited by your imagination of what you can do with this. It's actually pretty fun to do.

- Disorientation

- Question: “Where do you live now?”

- Answer: Name of Facility

- Question: “What is your room number?”

- Answer: Room #

- Question: “What is your address?”

- Answer: Client’s address

To help with disorientation, these types of questions can be asked if someone is new to the facility and may be confused. The important thing to remember is to make sure the questions are meaningful. I've had a lot of patients who really aren't used to the idea that they live in a facility, that they have a room with a number, or that they have a roommate. All of these things are very new and different for them. I actually had a patient who was a musician, so I put a music note on their door. Then, when I asked them, "How do you find your room?" that person would say to me, "I looked for the music note.” That was more meaningful to that person than a room number. Think about how learning and meaning are really connected to memory and how SRT can be the most meaningful for your patients. Maybe the question, “What's your address?” would be appropriate for a patient who's living on their own and needs to know what their address is if they need assistance.

Repetitive questioning is another issue that we might get referrals for. We might have challenging behaviors that our patients are exhibiting, and speech can often be the discipline that can intervene. For example, maybe the patient's always asking what time meals are served or did they have their pills yet or when is their daughter coming? There can be many things that cause the patient quite a bit of distress because they're asking that question over and over again. Maybe they're nervous about it.

Repetitive questioning can also be frustrating for caregivers. It can actually be one of the top stressors for caregivers because they are answering the same question over and over again all day. We want to think about both sides of the coin, not only the patient but the caregiver. You can use spaced retrieval to work on some of those repetitive questions. However, it is important to determine the root of the issue first. Is the person asking the question because they're seeking attention or because they're seeking information? If the person's asking over and over again when their daughter's coming because they just want the reassurance that comes with asking that question, then you could have them work with spaced retrieval all day long and it's not going to satisfy that person. But if the person legitimately does not know the answer to the question, then spaced retrieval would be a good fix for that.

The fastest way to know the difference is to ask that person their own question. Ask them, “When do you think she's coming?” If they don't know the answer, then we can possibly use spaced retrieval to help them remember that. Conversely, if they answer the question correctly, that she's coming at three o'clock, then you understand that the root of the problem is that they're searching for reassurance or attention. The fix for that becomes quite different. Maybe you're going to give reassurance and attention at times when the question isn't being asked and give that person what they need at a different time.

Examples of prompt questions and answers for swallowing include:

- Question: “What should you do before you swallow?”

- Answer: ”Tuck my chin”

- Question: “After you take a bite…”

- Answer: “Take a drink”

The prompt doesn't always have to be a question, it can be a statement, a command, or even a carrier phrase. If a person has difficulty expressing themselves, maybe they have dysarthria or aphasia, it doesn't have to be even a verbal answer. You can have answers that are physical in nature, where they're just showing you how to do something or pointing to something using AAC, a picture book, or a card. The point is, don't get stuck on the idea that it always has to be a verbal answer or a question.

An example for voice is, “What should you do before you speak?” The answer might be, “Take a deep breath.” If you're using a different kind of voice program, there might be some things that you want the patient to recall to be able to use.

Some safety examples are:

- Question: “What should you do before you stand?”

- Answer: “Lock my wheelchair breaks.” (This doesn’t have to be verbal; they could just do it.)

- Question: “How should you sit to protect your hip?”

- Answer: ”With my legs uncrossed”

What Happens After the First SR Session?

After the first session of SR training, we write down the longest time interval that the person demonstrated success. Then, at their next session, the very first thing I'm going to do is ask the person the prompt question. I want to see if any retention has occurred from our training from the prior day. I'm going to say, "It's great to see you. I'm so glad we're going to be working together. What is my name?" If the person looks at me and is able to remember that Megan is my name, then that shows me that they've retained the information for longer than four minutes or eight minutes. They've shown 24 hours or 48 hours of retention, which is amazing.

That means I don't have to backtrack and do these smaller intervals for the rest of this next session. I might say, "Yep, absolutely. That's great, you did remember my name. We're going to keep working together today." Then I might go ahead and proceed to the other goals I might be working on with them. Maybe intermittently throughout the session, I might ask what my name is, just to see if it's been retained. I am spot-checking to see if any retention has happened. Again, this is what happens after that first session when you started training a new piece of information.

What happens if they don't remember the answer after the first session? If the client cannot recall the answer, we will follow the same steps of providing the correct answer, asking the client the prompt question again, and having them respond with the correct answer to demonstrate immediate recall. Then I go back to the last time interval where they were successful in the prior session. For example, if they got up to four minutes in the last session, that's where I would start working on training during the current session. It’s the same process as within-session training. If they miss it, you provide errorless learning, you provide the correct answer, ask the question again, have them respond, and then return to the last interval where they demonstrated success. In this particular case that would be in the prior session.

Here is an example of what happens after that first session. At the start of any session following the initial training session on a prompt question/response, the clinician should allow the client to demonstrate recall of the information by asking the prompt question, “What should you do before you swallow? The answer was, “Tuck my chin.”

At the next session, I am going to say, "All right, let's go ahead and ask that question, what should you do before you swallow?" If they get it correct, I say, "Absolutely, that's great. Let's go ahead and have some of your meal and see if we can tuck our chin before you swallow." If they get it incorrect, then I'm going to say, "Oh, what should you do before you swallow?" If they're not sure, I'd say, “You tuck your chin. What should you do before you swallow?” Client says, "Tuck my chin," I say, “Good. Let's go ahead and take a bite.” Then I watch to see if they can tuck their chin. Then I would return to the last interval where they demonstrated success. In this case, in that session, it was eight minutes. So, I would start my timer at eight minutes to check to see if they retain the information.

When is an SR Goal Considered Mastered?

According to the research, we want to see a patient retain the information at the initial trial of three consecutive sessions. Like we said, after you've started training with somebody in one session, you're going to come in that next session and spot check, by asking the prompt question. If they get it correct, that would be one; one session where they got it at the initial trial. That means it's been 24, 48, whatever number of hours since your last session. Then, see if they could do that for three sessions in a row. That tells you that they're likely to retain the information pretty well.

The key is to make sure that we don't discharge too early. We want to make sure that they understand and are using the information that we're teaching them. If they got it right at the start of three consecutive sessions, but I go and check on them at a meal and they're not tucking their chin at all, that tells me that this hasn't been retained. I have to find another way to keep practicing this goal. Maybe I need to put a visual aid next to their tray to remind them to tuck their chin. Maybe I need to teach the staff to ask the question so that the person is prompted throughout their meal. There are a lot of things that need to be considered. So, the rule of thumb is three consecutive sessions. But again, use your best clinical judgment to decide when something is considered to be mastered. We want to see that consistent use of the skill that we're trying to teach the person.

How Much SR Training Does a Client Usually Need?

How much training needed is really determined by the client. Therefore, it's going to vary.

The number of sessions needed can depend on the individual’s level of cognitive impairment. It’s also dependent on the number of sessions the client has. If you're seeing them three times a week or five times a week, they're likely to get the answer much quicker. Whereas if you're just seeing them once a week, it might take more time. The number of sessions is also dependent on the number of goals you're addressing using spaced retrieval. You could address a number of different things. You could work on the patient tucking their chin before they swallow, as well as work on the names of family members. You can have some different things in play. I always recommend making sure that the goals are pretty different from one another so that people aren't getting confused by all the questions. Again, the more frequently you see patients, the more likely they are to retain the information faster or attain the goal faster.

Spaced Retrieval Goals

Goals aren't written any differently for spaced retrieval and the possibilities are endless. SR goals are not written any differently than your other goals. If they're SMART goals or written according to the International Classification of Functioning Disability and Health (the ICF Model) then you're in good shape. You can add the use of spaced retrieval to your goals, but just keep in mind, this is just a method to use.

Just like you would use other different methods to work on goals with your patients. You can either include it or not include it, but the goal is still going to remain the same for what you want your patient to be able to do. There is a mapping tool from CMS that can assist you in understanding the ICF model better (link: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Billing/TherapyServices/Downloads/Mapping_Therapy_Goals_ICF.pdf). But, again, keep in mind that a functional goal is a spaced retrieval goal; and that's what's important.

Here are a couple of examples. Measurement of goal attainment can be determined by the area of focus and what allows for the best measurement of progress. For example, you could do it by a percentage or the number of trials:

“Client will recall and demonstrate the ability to use compensatory swallowing strategy to decrease choking and aspiration risk, 80% of trials.” There is no mention of spaced retrieval in that goal. You're just wanting them to be able to recall and demonstrate the chin tuck or whatever compensatory strategy you chose to use. And you want them to do that strategy for a certain number of trials. But the methodology you're going to use is spaced retrieval, and the way you can look at the retention of that information is by using the spaced retrieval technique.

Here's another example: "Client will recall and demonstrate the strategy of locking wheelchair breaks prior to standing to increase safety and reduce fall risk at the beginning of three consecutive sessions using spaced retrieval.” I might even put in parentheses what spaced retrieval is. We know that the people reviewing our documentation often aren't SLPs so we want to make sure that they're aware of what we're doing and why we're doing it.

Again, SRT is just a modality or approach. It doesn't fit one particular diagnosis category. You use the ICD 10 code that corresponds to the goal you're addressing. If you're working on swallowing, that's the ICD-10 code you would use. If you're working on voice, that's the ICD-10 code you would use. Spaced retrieval is just another tool in your toolbox that will help your patients retain information.

SR Decision Making

There are some things to consider when making decisions for SR. What are the strengths of the clients? Always think about what abilities are present and, then, what are their weaknesses? Do they have a physical impairment or visual impairment? You might want to use large print or high contrast print with black print on white background. Think about the lighting to assist a person with seeing external aids better.

If their vision is poor, maybe something like pressing a button would help or put a little sandpaper or puffy paint on an item so they can feel it better so they can access what they need.

What are the challenging behaviors that are being exhibited? Again, this is a great place for speech to intervene because we have such a good understanding of how behavior is really a form of communication. What are people seeking, what do they need, and how can we assist with that? Are they wandering into other people's rooms or demonstrating some inappropriate behaviors? Find out what the root causes are. Is it something that we can teach the person to find the information or find an alternative to what's causing this to happen? We might be able to use spaced retrieval as an approach to assist with those things.

What are the prompt questions and responses that'll be used and is it meaningful to the client? I can't stress this enough. You might come up with a prompt question/answer that sounds great in theory to you, but makes no sense to the client. There have been many times that I have changed the question or the response based on what the patient is telling me that they need. Be sure to make it meaningful.

I had a woman I was trying to teach to use the call button in her room to get assistance. And I kept using the idea of “call bell” and “What should you hit if you need help?” She just was not retaining it. Finally, I asked her, "Well, what would you call this?" And she said, "Oh, that's a taco bell." (She loved eating taco bell.) So, that was the response we went with. It might make sense to you, but it may not make sense for the client. Learning has to be meaningful. Ask your client, "What would you call this?" They might not call it a memory book they might just call it a photo album. Go with that, that's okay.

Also, think about the length of the question. Is it too long or too confusing or too abstract? You might have to make some changes. If that's the case because the patient keeps missing the answer, then make those changes and see if it makes a difference. It's completely okay to start from scratch and see what happens.

Finally, think about who might be involved in the training. What other family or staff members should be included to assist with carryover. You're going to want to teach people what questions to ask to help a person when they're trying to transfer, or when they're at a meal. Do they know to ask, “What should you do before you swallow?” And the patient remembers to tuck their chin.

SR: An Interdisciplinary Process

If you involve caregivers and family, you're going to have much better buy-in and cooperation. Ask them questions like, “What do you usually say that helps calm this person down?” “What do you think would be a good question to ask them?” “What are some things that are important to you as a family member or you, as the patient, that you would want to remember?” Starting from there can really make a big difference because a lot of times our patients have this idea that they can't learn anything new. They're really upset about their diagnosis, which can make complete sense. Our families feel the same way. We want to give them some hope. Ask them, “If you could remember something or you would want to remember something, what would it be?” If we start there and show them that this is something that actually can work, then they might buy into some of the other things we want them to remember. We can share those prompts and responses with the family and staff to allow for that consistent use.

Case Study

Let’s end with a case study. This is a 75-year-old male who is a resident of an assisted living facility. Diagnoses include Parkinson's and Mild Cognitive Impairment. He was referred by his physician to receive speech therapy through home health upon discharge to home. The patient is experiencing cognitive decline, is at risk for falls, and is experiencing a decline in vocal function. The patient's goal is to remain at home and independent as long as possible.

Examples of some possible goal areas are working on voice with this patient, and memory and executive functioning. We could work on managing freezing episodes when completing mobility-related activities to reduce fall risk or completion of a home exercise program.

The goal that I used as an example is, “Patient will recall and demonstrate strategies to manage freezing episodes during movement to reduce fall risk at the initial trial of three consecutive sessions using the spaced retrieval technique.” If you're not familiar with Parkinson's disease, patients can have freezing episodes which are sudden, short blocks of movement that can occur when a person initiates walking, turning, or maybe navigating narrow spaces. They kind of freeze in their movement.

If PT is working with the patient on their gait and their transfers, but the patient isn't remembering what kinds of things they can do to get out of a freezing episode, this may be where speech comes in and we can ask a prompt question, “What should you do if you freeze?” Then we can give them some strategies, and there are some very good strategies that are recommended by the American Parkinson's Disease Association such as try another movement, raise your arm and then touch your head, and then try to walk or change direction; or start to sing a song, or say 1, 2, 3, and then take a step. There are many different strategies that can be used.

We could use spaced retrieval to help that patient remember what strategies to do. I could use the prompt question, “What should you do if you freeze?” They would respond with any of those strategies mentioned above. Maybe I would write the strategies down on a notecard and attach it to their walker so they can see them, “Where should you look when you freeze?” They answer, “At my card.” Then we would work on them using the card in order to get out of that freezing episode. That's just one example out of many that we can work on using this technique with this particular patient.

Questions and Answers

On the Spaced Retrieval Screening tool, why is the number 3 circled for each step?

If the person gets a 3, that's where they might exit out. If they can't get past 10 seconds, then the screening says to proceed directly to the exit line.

So, if they can't quite get it, as you go back and forth, then you're going to exit them out. That doesn't mean that they can't do spaced retrieval at all. I might go back at a later time and try it again with this patient and see if they can do it. Maybe I’ll try it during a different time of the day. Maybe the first time I gave the screener it was late in the afternoon and they were tired or distracted. Maybe there's an alternative where you can write down the name of the person in the picture and see if the patient's able to remember it by reading it. That's another way for them to possibly pass this screen.

Can orientation to the month be used as a prompt question?

I think it would be a little more difficult to do. I would prefer to ask, “How can you find what month we're in using the calendar?” I want them to be able to be oriented as often as possible. So, I would try to teach them a strategy of going to their calendar or looking at the newspaper or something like that.

Does spaced retrieval assist our memory for things that have not been rehearsed, for example, practicing a brother's name leads to retrieving other family names?

It really has to be pretty specific practice for each thing. In this case, if I'm working with patients to remember the names of several family members, I might have those in a memory book or something like that. Then the prompt question would be, “How can you find what your family members' names are?” Maybe the memory book has each person's picture with their name under it. Then they can read through that when the family's visiting, when they're working with staff, when they get up in the middle of the night. This gives them more and more repetition; more priming to that information. Again, the more rehearsal of that information, the better that retention's going to be. The other thing I might do is teach the families to wear name tags when they come to visit. Why make it harder? If they learn that they can find the name of the person they're talking to by looking at a name tag, then that takes some of the pressure off and makes everything a little better. Having those sticky name tags available and teaching family and staff that this can be a way to calm a person down, to have them feel more confident, and to have that connection happen earlier, is such a better way to go.

How do I handle repetitive questioning such as, “Can you fix something for lunch?”

You can ask that person, "Do you need to eat?" You want to always find out what the root problem is. Why is the person doing the behavior they're doing? There's always a root cause. For repetitive questioning, you might want to answer that question or ask the person their question back and see if they respond. That could give you an idea of whether or not it's something that they either need to learn a response to or if they're seeking something else.

I have a father-in-law who has difficulty remembering that his wife passed away.

This is so difficult, I know. You have to think about if you really want to orient somebody or not with that type of information. However, sometimes it can be useful to be able to walk somebody through the idea that the person is no longer here. It depends on what's going to set that person off. If a better reality is for them to think that the person is coming back soon, then you might go ahead and go with that response. If they really want to know and are somehow calmed by the idea that now they know where this person is, then using something like the obituary or a picture of the gravesite might be assistive. It all depends on the patient and how upset they might get with that information. But I think going ahead and kind of seeing what's worked and what hasn't worked could be a good place to start.

Does SRT work with long-term brain fog with COVID?

It hasn't been tested yet since we're still figuring out what's going on with COVID, but I would say try it. Memory is memory. It might work with people are who are neuro-typical as well as those who are having difficulties. So, give it a shot. It could help with remembering anniversaries, taking out the trash, those types of tasks for family members, etc.

Citation

Malone, M. (2022). The Spaced Retrieval Technique: A How-To for SLPs. SpeechPathology.com. Article 20503. Available at www.speechpathology.com