Editor’s Note: This text is a transcript of the course, The Role of Executive Functions in Social Interaction, presented by Dr. Lisa Audet, PhD, CCC-SLP.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Define the various executive functions.

- Examples of how deficits in executive functions influence social skill development.

- Describe at least 2 strategies to address social skills integrating knowledge of executive functions.

Introduction

I have been working in the field for over 30 years and my understanding of autism has become deeper over those years. I'm very pleased to share the knowledge and information that I've gained from working directly with individuals with autism. They have been my best teachers.

In this course, I plan to address social deficits in people with autism. We'll talk about executive functions and how to apply executive functions to social deficits. I will also discuss a number of strategies related to executive functioning and social skill development.

When I first started in the field, we would work on social skills with worksheets. If you are as old as I am, you might remember working on eye contact by filling out a worksheet (as if that would do anything). So, we've come a long way and I have come to understand that social skill development is related to cognitive development. We use our cognitive skills as we socialize. What we see in terms of social skills, such as somebody invading another person’s space, saying something out of context, or not being inhibited in what they say, that's really the tip of the iceberg of what’s going on neurologically and cognitively.

Based on that, I've come to the understanding that my social skills therapy needs to be grounded and connected to cognitive development; and neurological processing and executive functioning support that.

Grice’s Maxims

The work of Diane Williams has been very influential in my increased understanding of this connection. Of course, we have the work of theory of mind that has been around for a number of years as well. But Diane Williams has been doing work with fMRIs, and looking at what's happening in the brain as somebody is engaging in a social task.

A framework that I'd like to share is Grice's Maxims, which you may have learned about in a linguistics class, a language class, or a psych class. It’s a general framework for understanding what's happening when people with autism are engaged in social activities. The research indicates when we use Grice's Maxims, that awareness of a violation increases with age in typically developing individuals. We become more sensitive to those social “faux pas” as we get older, which makes a lot of sense. We also know that the ability to recognize a violation in ourselves and the ability to repair that violation is critical. For example, there is the social pragmatic function of requesting clarification and providing clarification. Those skills are intrinsic to effective social skills development. But you have to be aware that there was a violation so that you can repair it.

We also know, with the help of Diane Williams' work, that flexible thinking, which is an executive function, is linked to adaptive behavior. People who are better at flexible thinking can adjust their behavior accordingly. If we think about people with autism, one of the things that they struggle with is flexible thinking. I also know a lot of people who don't have autism who struggle with flexible thinking and get very upset if something doesn't happen the way that they wanted it. So, it's not just people with autism, but certainly, flexible thinking is something that people with autism tend to struggle with and it affects them socially.

Working memory is another executive function that is related to adaptive behavior. So, executive functions are related to adaptive behavior; the ability to navigate the world in an adaptive way. Notice, I'm not going to use the word “appropriate” or “inappropriate.” I'm using “adaptive” because adaptive means that we're meeting the demands of the environment. Maladaptive means we're not meeting the demands of the environment. So, we see these executive functions of flexible thinking and working memory influencing our ability to adapt to the environmental demands and, as such, leading to better social skills.

There's a linkage that we've overlooked for a long time in terms of how social skills work. We focus on, “my turn, your turn, my turn, your turn.” We give a lot of feedback to individuals with autism as we work on their social skills. But are we actually addressing the executive functions that they need to develop in order to have better adaptive behavior and better social skills or are we just doing the tip of the iceberg?

Again, these four points are important to keep in mind as we look at Grice's Maxims and his four maxims are below.

Quantity (Informative)

Is the information informative? Is it just the right amount? You have to think, "If I'm going to give the just right amount, I need to be aware of my partner's perspective and adjust that amount accordingly.” It is kind of a dance and I'm doing that dance during this presentation with you. I don't see any of you, but in my mind, without your direct feedback, I am continuing to adjust how much I say, how fast I say it, all of those nuances, so that this will be a meaningful experience for you and I’m doing it without feedback from you. As I say that, for individuals with autism, that might be part of their difficulty. Even when we're in front of them and giving them visual feedback, that difficulty with flexible thinking and changing or adapting their behavior is so difficult. They can't make those adjustments. The information has to be informative and it is informative when we can adjust the amount and provide relevant information.

Quality (Truthful)

Our second maxim is quality. Is the information truthful and honest? Does it take into account what the other person's perspective might be? Is it open to other perspectives and recognizes that things can be a different way? Think about your client who, for example, talks about whales and give a lot of information about whales. They're violating quantity because they’re not giving just right amount. Furthermore, if you were to interject and say, “Oh, I went on a whale watch,” they would not be able to take your perspective and integrate that into their conversation.

Relation (Relevant)

The third maxim is relation which is the relevance of the information. Can the individual follow along with topic shifts? Can they begin to shift the topic and understand what's important information? Are they focused on so much on the nuances or tangential information that they're not able to read between lines? We all do a lot of work helping individuals understand figures of speech and idioms, etc. which is great from a semantic perspective. But when those figures of speech are integrated into a conversation, can the individual see how those figures of speech are relevant to the conversation? For example, if somebody was watching the Olympics and said, “He won by the skin of his teeth,” would the person be able to see how “skin of his teeth” is relevant to that particular conversation?

Manner (Clear, Brief, Orderly)

The last maxim is manner which is where we can adjust our style and go. We can pace our communications based on what we perceive as the knowledge base of our communicative partner.

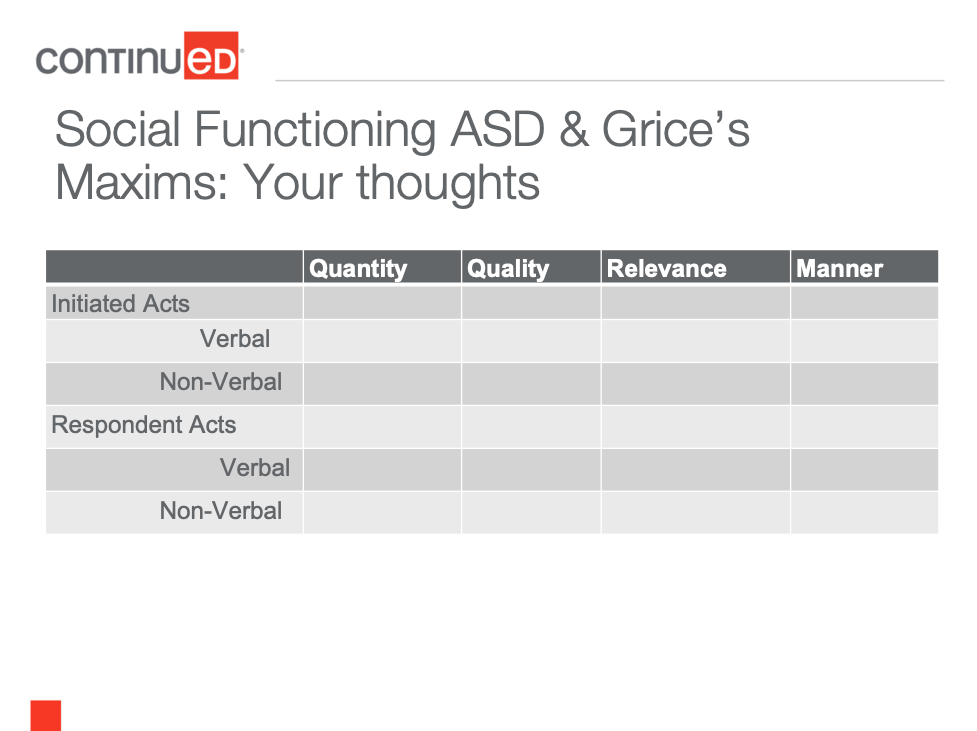

Social Functioning ASD & Grice’s Maxims: Your thoughts

Let's take Grice's Maxims and apply them to the social functioning of people with autism. I’d like you to record your thoughts based on your experiences with your clients. Think about those individuals and jot down some notes. As I continue to go through the course, think about how these original, initial thoughts apply to the strategies and executive functions that I will discuss.

Below is a table (Figure 1.) to help you with your thought process.

Figure 1. Social functioning ASD & Grice's Maxims: your thoughts.

The y-axis shows initiated acts, such as social interaction. We initiate verbally and non-verbally through eye contact or pointing, for example. As human beings and social beings, we also respond (respondent acts). Someone says something to us and we respond verbally letting them know, “Yeah, I get that” or “What did you mean by that?” We use pragmatic functions as respondents and we also use non-verbal behaviors. For example, teenage girls roll their eyes. I know that is stereotypic, but they do. They grimace. So, we have nonverbal respondent acts. Some clients with autism may respond by pinching or biting or pushing you away. Some people with autism may initiate by taking your hand or by squealing.

Looking at the x-axis, we can ask ourselves what is the nature of the quantity aspect of the person's initiated acts? Meaning, does the person with autism provide enough information? Are they being informative verbally or non-verbally? A problem with quantity suggests that the person is not providing us with information.

The next column is quality. What's the nature of the quality of the person’s initiated acts? What's the nature of the quality of their respondent acts? Are they adjusting for somebody's perspective? Are they realizing that what they just said might be hurtful? Are they recognizing that they're not being flexible when they initiate or when they respond?

The third column is relevance; that reading between the lines when the person initiates. It’s being on topic when they initiate. How relevant are their initiated acts? Is that an issue for your client? How relevant are they when they are responding to acts? You might see this with individuals who are echolalic. They have difficulty with relevance as their respondents. At the surface, that echolalic response may seem to not be relevant to the conversation. However, other individuals who might not be echolalic, can get hung up on a particular topic. We want to think about that.

Lastly, is manner. What is the person’s manner, or ability to adjust their vocabulary based on their partner? Are they thinking about their pace or their pausing, etc. I work with a young adult who is getting his PhD in public health. His vocabulary is incredible. But he doesn't always adjust it when he's initiating and when he's responding. It can be a real turnoff for people. It can appear that he is talking down to others and it's something that he's working on. We've actually used Grice's principals and executive functions with him to increase his ability to plan and make a choice about how he's going to behave.

This brings us to another critical point. As we do this work and think about executive functions as they relate to adaptive behavior and social skills, we are not trying to make the person with autism be “normal.” We're trying to give them skills so they can make choices about how they interact. We all do that. We all make choices about how we're going to interact. You make a choice about whether or not you're going to make a snide comment to a colleague or to a spouse. You make a choice and that ability to make a choice lives in your executive functions. It's not that we want individuals with autism to behave like robots. We want to give them the skills so they can adjust their manner as a choice. There might be times where they choose to not adjust their manner. But we want them to have the ability to make that choice.

Executive Functioning

Let's talk about executive functions. I've consolidated information from a number of different sources and there are a number of references at the end of this course, but the following are the main executive functions.

- Inhibition: The ability to control what you say and what you do

- Shifting Attention: Focusing on what's salient or urgent

- Emotional Regulation: Managing your feelings about what has been said or what you are saying so that you are rational

- Initiation: The ability to evaluate your thoughts and events in order to take action. For example, thinking something through and saying, "I'm going to introduce the topic now. I'm gonna start this now."

- Working Memory: While engaging in a social interaction, you are able to judge, analyze and synthesize, in order to make a change. Based on your prior knowledge, you're going to change what you're doing. Think about day-to-day interactions. For example, you know that if you call your mom and say something, it might trigger a cascade of interactions. You know that's the history and you just don't want to go there. What allows you to say, “I'm not going there,” is your working memory. It’s saying, "Based on my history, if I say X, this is what's going to happen.”

- Planning: This allows you to be more sequential in interactions. It’s linked to the quality and quantity of using Grice’s Maxims.

- Organization: Thinking about and expressing yourself in a rational, orderly manner so that you can follow along. Many of our clients have difficulties with pronouns and have limited vocabulary. As they're telling a story, it can be really difficult for the listener to follow along with the different characters in the story.

- Self-monitoring: The ability to have flexible thinking and thinking about, “How am I coming across? Do I need to change anything so that I don't lose my partner’s interest?”

Adaptive and Maladaptive Ways of Engaging Executive Function

Inhibition

- Adaptive: Adaptive behavior would be biting our tongue, keeping our mouth shut, controlling physical behaviors when we're emotionally charged. We stop ourselves.

- Maladaptive: Maladaptive behavior for inhibition is being insulting or reporting when peers break rules, such as, “You said that we weren't supposed to sit on the blue chairs and he's sitting on a blue chair.” The person doesn’t realize that the rule isn't really all that important, but they can't stop themselves from saying something like that. Non-verbally maladaptive might be the pinching or biting that I mentioned before.

Shifting Attention

- Adaptive: Knowing what is and what isn’t important to talk about. You can consciously say to yourself, "Oh, you know what, I'm going to save that comment. I'm not going to talk about that right now."

- Maladaptive: Does the individual persistently ask the same question, talk about the same topic, ruminate on a problem, have difficulty moving or shifting their attention to something else that is more salient?

Emotional Regulation (This pertains to self-talk)

- Adaptive: We all use emotional regulation. We talk to ourselves to stay calm. We say things like, “I'm not going to let this bother me.” We deescalate ourselves so that we're not wasting our internal resources on something that's going to be upsetting.

- Maladaptive: Maladaptive emotional regulation would be, for example, responding the same way to someone sitting in “your” seat as you would if you physically hurt yourself. Both events create the same level of high-intensity emotions. Some individuals, in terms of social skills, really need to work on emotional regulation.

Initiation

- Adaptive: Recognizing when to stay quiet, to act, or to interact. For example, if you see a familiar person at a gathering or in a store, you think to yourself, "Should I say hi? Should I not say hi?" We take in a lot of information before we initiate and take that risk.

- Maladaptive: Individuals on the spectrum who might have problems with initiation, might need a prompt. They might wait for somebody to say something because they are more of a responder and less of an initiator.

Working Memory

Adaptive: Adaptive working memory is taking past experiences and using those to inform ourselves on how we're going to act now.

Maladaptive: This is when an individual talks to a peer in the same way that they would talk to the principal. They can't take into account that because this is a peer, they should adjust their manner. They need to adjust the quality of the interaction as I'm talking to the peer. Another example is the individual who makes the same mistakes over and over again socially. Even though we may have addressed that mistake with them, they continue to make it. This might be happening because the person has difficulty with working memory and needs us to put supports in place to aid their working memory proactively.

Planning

- Adaptive: Being sequential and methodical. For example, I want to talk to you about X, so I introduce the topic.

- Maladaptive: Maladaptive planning is jumping into a conversation. The person didn't really read the environment before jumping into the conversation.

Organizing

We have many clients who have problems with organization, especially if they also have attention issues.

- Adaptive: Using a schema in order to be methodical about what is being presented. Story grammar is integral to organization. It's a schema. In social interaction, we rely on story grammar to relay past events. It’s important to think about this as you're working on your social skills with your clients. If organization is an issue, what can you do to support their use of story grammar?

- Maladaptive: Introducing irrelevant topics, providing more information than what the partner needs, or not giving enough information.

Self-monitoring

- Adaptive: Self-monitoring is knowing when you need to apologize, when you need to make a new plan, or when you need to provide clarification or more information.

- Maladaptive: Continuing to do what isn't working and not knowing how to change it. Some individuals might need to use rating scales to rate their awareness of the impact they have on others and we talk about that. They might have real deficits in self-monitoring.

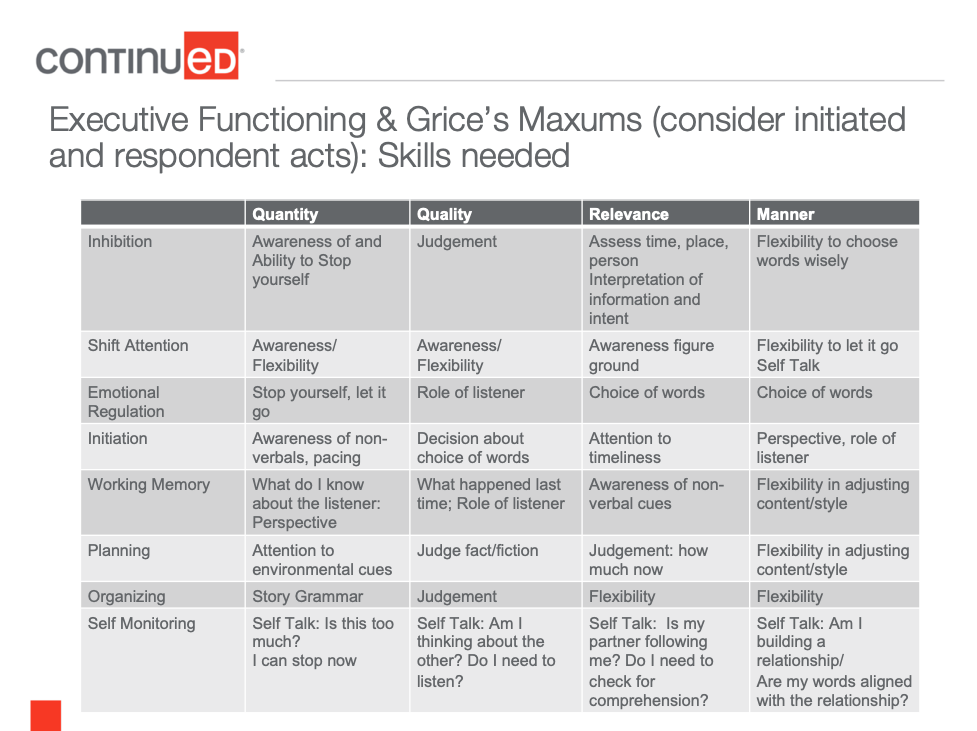

The below table summarizes what we've just discussed and applies the executive functions to quantity, quality, relevance, and manner. It can be used as a “go-to chart” to address the various executive functions (e.g., If this is happening, then I'm going to do the following.)

Figure 2. Executive functioning and Grice's maxims: skills needed.

Let’s look at the executive function, organizing, as an example. If your client has difficulty with organizing and it's impacting the quantity of their social interaction, you can use a story grammar approach. If their organizing (or inability to organize) is influencing the quality of their social interaction, you can work with them on making judgments and using some rating scales to judge their effectiveness. If the problem with organizing is flexibility of thinking and it affects relevance, there are some strategies that you can work on to address flexibility.

Critical Aspects

There are some critical aspects to think about as we move into strategies. The first one is perspective-taking. This is the client's ability to interpret the context, the person's intent, and their own intent. Do we talk to our clients about perspective-taking? Do we ask our clients, “How do you think that person feels?” Do we ask, “Why do you think that person said that?” Are we engaged in activities that encourage perspective-taking, which also encourage self-monitoring and flexibility of thought? Do we talk about that or do we simply say, “You are off-topic” or “You can ask that question four more times and then all done.” Those two strategies are not effective because they don’t address the reason why the person is asking those repeated questions or why they are off-topic. Instead, we need to address the underlying nature of the problem.

Another critical aspect is helping our clients manage both internal and external distractions. For example, we may need to help with shifting attention. Recently, I was working with a five-year-old boy and I touched his back. He immediately pulled away and put his hand on his shirt. I created an internal distraction. My intent was to be kind, but his sensory system was such that it created a distraction and caused him to lose his train of thought.

The next critical aspect is flexibility. Do we engage in work with our clients that encourages them to be flexible? Are we providing choices and responding to their intent? Are we encouraging that or are we so regimented in our interactions and our activities that we are actually encouraging inflexibility?

Diane Williams often talks about how we can be so over-programmed in our interventions that we're not supporting the development of flexible thinking or problem-solving. Do we jump in to solve their problems? That would inhibit flexibility.

Do we engage in behaviors, as therapists, that encourage our clients to judge or reflect upon what just happened (e.g., “How do you think that went?” “What do you like about how that went?”)? Are we engaged in conversations with them that support the development of executive functions or are we just giving our clients feedback and want things to be done a certain way?

Do we draw our client's attention to things they need to be aware of? For example, “When you go in the cafeteria, I want you to be aware of who is sitting at the table and if they're talking.” Are we talking to our clients like that? What would happen if we did? Would we be supporting executive function?

Are we encouraging them to assess an interaction? Can they recognize when there is a violation? If there was a violation, we can teach them that they can go back and repair it. Ask them, “What can you do to make it better?” A lot of times, particularly with the younger children, if there's a violation, we have the child sit in time out or they lose something. There's some kind of punishment. But do we ever move back to repair it? It might be wise for the person to take a moment and remove themselves from the interaction and calm themselves. But when I have somebody take a moment to calm themselves, their task is then to figure out how are they going to make it better? What's your plan? When they come out of “time-out” or their “thinking chair,” they need to follow up with their plan. They can make an apology, write the person a letter, whatever it might be that they want to use to repair that violation.

The last critical aspect is emotional regulation which is so connected to self-monitoring. We have all learned so much about the importance of being in a calm, alert state in order to have an effective interaction. Otherwise, you're just too aroused or under aroused to bring any kind of cognitive energy to the interaction.

For many of our clients, these two executive functions are very critical. We spend a lot of time working on helping them come to a calm, alert state so that they can be ready for the interaction. We can't work on anything else until they're able to sustain a calm, alert state.

Application of Executive Functioning to Social Functioning

Let’s consider the connection between cognitive skills or executive functions and social skill development. We want to provide the individual with some tools that can build the bridge between their cognitive ability and their social skills. Our intervention can act as a bridge between cognition and social skills. We want to engage in activities that will strengthen those cognitive skills, those executive functions, so that our client can be more effective socially.

T.H.I.N.K.

There are a few different methods to do that and one of them is the acronym, T.H.I.N.K. We can describe it to our clients as the five rules that we will follow and think about as we interact.

- Truthful - Was what I just said truthful?

- Helpful - Did it help to build the relationship?

- Inspiring - Did it inspire that person to want to be connected to me?

- Necessary - Was it necessary? Was it something related?

- Kind - Was it kind?

We could very easily take this acronym, and turn it into a 1-5 rating scale where our clients rate themselves on how truthful they were, how helpful they were, how inspiring they were, et cetera. We could rate them and then discuss if our ratings are similar or very different. If the ratings are different, we could have a discussion to provide clarity about what truthfulness is, for example. If I think the client is a 2 in truthfulness and the client gave themselves a 5 then they are not demonstrating awareness of that rule.

These types of rating scales use some simple terminology and we can change some of these words. But these five words are very useful in thinking about Grice's Maxims. Using this as a rating scale is very useful to learn more about your client's awareness and perspective and self-monitoring.

Problem-Solving Tree

A problem-solving tree is basically where you have a situation such as Charlie is sitting at your seat in the cafeteria. So, what can we do? If you do A, what might happen? If you do B what might happen? We actually illustrate what the options are so that they can then make a choice. It’s a way to make a plan.

In many ways, this is taking a social story and turning it into a problem-solving tree with more options. Remember, the goal is to build executive functions so that our clients have choices for how they want to behave. There is not just one way. We want them to be flexible.

I have a young lady who is getting a PhD, and as she's working with clients, sometimes she has difficulty if they “don't know their script.” That is how she describes it. She has an idea of what they are supposed to say. So, we've been using problem-solving trees to help her understand that if our client says A, then we need to make a different choice. This is a much higher-level example with a brilliant person with autism who is using this problem-solving tree as an effective strategy. It may also be effective for some of you who are working with high school students who want to start dating, want to tell jokes, or want to interact. We can illustrate these social skills with a problem-solving tree and talk about flexibility and awareness of what their partner is doing.

What If…

As we go through the problem-solving tree, we should be aware that our clients might not have deep knowledge of mental state verbs such as, “I want you to think about this. What do you know about this? Is that a guess? We may need to do a lot of work teaching those mental state verbs, especially if we’re working with younger individuals or more involved individuals. When was the last time you asked a person with autism, “What do you think about that?” We need to be asking that question more often if we want our clients to develop executive functions.

Our clients might not have causality (e.g., if A then B). Additionally, we have students who have a really hard time losing. A problem-solving tree may be really helpful for that because playing a game, and possibly losing a game, requires planning for what to do if you lose. Being able to manage your emotional state and inhibit any actions that could be maladaptive requires executive functions. The problem-solving tree can help with discussing this in advance.

Self-Talk

Another strategy is self-talk. Vygotsky, a well-known child psychologist from the 1930s, talked about the importance of self-talk. He stated that what separated typically-developing children from those with disabilities was the absence of self-talk. Children with disabilities were not talking to themselves. They did not have that internal voice. It’s that internal voice that we use to inhibit our actions and to keep ourselves calm. We need to do more work and teach children with autism to engage in that positive self-talk to manage their behaviors adaptively.

I like to use “one-liners,” or quick statements, to help with self-talk and self-monitoring. If you are trying to figure out what the self-talk line should be to teach a child or client, think about what you say to them all of the time. For example, you might say, “Eyes on work” or “Keep safe hands.” Those are quick statements that our clients and students can start saying to themselves so that we don't have to.

Some examples of quick statements include:

- See it & Say it (or Save it)

- Need it or Leave it

- Action or Passion

- Do it or Glue it-stop

“See it and say it” (or save it) can help with impulsivity. The child sees something happening, do they need to say it or should they save it (i.e., keep it to themselves). An example would be, “You're going to go in the classroom and there are going to be students who are misbehaving. You need to think to yourself, ‘See it, say it, or save it.’”

You can write the statement down for them too. I had one young student who had different stickers that represented different self-talk statements. This allowed the teacher to touch the character on the sticker and that would be the student’s self-talk line. I had another client who had a recipe box with the little cards in it that had the different self-talk lines for different contexts, such as playing on the playground or taking a test. So, play around with this idea and if you find that your client really needs to develop more self-talk to manage impulsivity, self-monitoring, or emotional regulation, you can create different ways of doing it.

Another self-talk statement is, “Need it or leave it.” The student asks him/herself, “Do I need it or should I leave it?” “Do I need to say this or do I need to just let it go?”

“Action or passion” refers to, “Do I act or do I show kindness?” “Do it or glue it” means, “Do I do it or do I glue it and stop?” This is a phrase that they might say to help them manage their impulsivity.

Another word for impulsivity, planning, self-monitoring, and emotional regulation might just be saying the word, “pause.” They learn to say to themselves, “pause,” to take a breath and pause. They can write it down or you can write the word down and then tap on it and they say it, “pause” or “put it on pause.”

Another self-talk phrase is, “Stop, think and make a plan.” I use a stoplight when I'm working with young students. Red is stop, yellow is think and make a plan, and green is whatever the plan is going to be. I will Velcro plan options that they can pick and put on the green light for their plan. This is done proactively. For example, before the child goes into the hallway to stand in line, I ask them, “What are you going to do?” They will say, “Stop, think, and make a plan.” I ask, “What's your plan?” They respond, “Stay in line.” So, a picture of staying in line goes on the green light.

Another word might be “steady.” They can say this word to themselves to manage that impulsivity. If there is the tendency to ask questions repeatedly, we can teach them to say to themselves, “Steady. Stop, think, and make a plan. I'm going to write my question down.” A similar word to steady is "settle." This self-talk word can really help with emotional regulation.

Circle of Friends

You may be familiar with the idea of creating circles and talking about the relationship between you and another person. How close you are to this person? What would you say to this person based on how close you are to them?

Circle of Friends (https://www.circleofriends.org/program-description) is actually a diversity and inclusion program for understanding each other's perspectives. It is equitable meaning it's not a situation where there is a peer mentor who doesn’t have autism and he or she is going to take care of the person who has autism. This is truly two people learning about each other. The person who doesn't have autism is learning from the person who has autism and relating to that person as an equal versus continuing to look at him or her as less or having a disability. The dynamic of a social interaction immediately changes when that philosophy is adopted.

Key Points

Let’s move on to the key points. First, everything that I've discussed in this course needs to be done proactively. We need to be thinking about and developing executive functions before the problem occurs and we need to do it consistently. We need to be integrating strategies to work on those executive functions all the time.

As we develop these cognitive skills, we are supporting social functioning. What strategies and tools are we using to do that? Are they effective? If they are not effective, we need to change them.

Additionally, instead of having our clients wait for us to say, “good job,” which is an extrinsic reward, we want to work on self-evaluation, self-monitoring, and emotional regulation so that they can recognize for themselves when they need to make a different choice. In the clinic, I do not allow the graduate students to say to clients, “Good job.” They need to say, "You worked really hard on that. What did you like about that?" I do not want our clients becoming so tied to our meaningless “good job” that they can't evaluate for themselves.

Lastly, we want to link to the individual’s personal goals when we can. When we have clients who are capable of talking about things like would like to do, we need to talk with them about the skills that they will need to get there and link that back to executive functions.

Questions and Answers

What are tips and strategies that you suggest for nonverbal clients to increase their executive function skills?

I did a presentation on play for speechpathology.com and in it, I talked about habits of the mind. You can watch that course (Course: 9391) or you can look up, “Habits of the Mind” to see a list of different habits that encourage individuals to be learners and develop those executive functioning skills. Persistence is one of the habits of the mind and is linked to executive functions, working memory, etc. One tip would be to not solve a problem for a non-verbal client. If a non-verbal client, for example, is trying to open up a busy box during play and they can't do it, very often, we put our hand over theirs and we turn it to open it. Instead of doing that, wait for them to ask for help. Let them take your hand and put it on the box to open the item. In that way, they're learning flexibility. They're learning how to request help and they're learning how to persist. We are encouraging them to develop problem-solving skills.

Again, look at those habits of the mind and how they are defined. Then, ask yourself, “What can I do in my therapy to support the development of these skills?" A phrase that I like to use is a “child-size problem.” If I'm working with a child and they have a problem that is a child-size problem, then I let them have their problem. I don't step in and solve their problem in therapy. However, if I am a parent and I have to get out of the house, I might step in and solve their problem because we're running late. But in therapy, I don't need to do that. I can let them have their problem.

What is a strategy that you can use to develop the ability to code shift in an interaction?

By code shifting, I'm assuming you mean relating to how well they know the person. I think doing those relationship circles and mapping people out (I'm really big on using any kind of visual that you can create and look at where that person falls in their relationship). Then looking at what you might say to somebody who is related to you in that way or close to you in that way. The peer program out of UCLA does a lot of work with code shifting. If you're not familiar with that, they have some excellent ideas there. For me, it starts by mapping the person out onto some kind of graphic and then talking through or making lists of what is okay and what isn't okay to do or say with somebody based on their relationship to you.

How do you redirect children on the spectrum who deliberately exhibit maladaptive behaviors when interacting with others because they enjoy the negative reaction, even if they are aware that their behaviors are inappropriate?

That's an interesting question because of the whole issue of “they're doing it deliberately.” What they're looking for is social interaction, and they're getting it because it's really big, right? They are getting a big response. So, I would also ask myself, are they under-responsive and, therefore, need that big reaction in terms of emotional regulation? The other thing I would do, and I'm assuming that this individual's probably lower functioning, is to use problem-solving trees or social stories with them. I would use the “stop, think, and make a plan” self-monitoring with them because you know how they're going to behave. You know that they're going to do something maladaptive to get attention to get this big negative reaction. So, we need to really be proactive either with a social story, a problem-solving tree, or “stop, think, and make a plan.” I had a client that I used “stop, think and make a plan” with when he was younger because he was very much like that. He would run up to somebody and kind of tackle them. But he had so many sensory needs. We used “stop, think, and make a plan” and then we would evaluate. I would say, “You did really well walking in the hallway. If you do this five more times, you can do X (you build in a behavioral reward system there). So, those are three things that I would consider depending on the student’s level of functioning. It might be that you start with that stoplight of “stop, think, and make a plan” and have Velcro options of, “I keep my hands to myself” or “I say nice things” as the positive adaptive behavior.

In regards to topic shifting, what do you suggest to help individuals with difficulty changing topics or students who focus on one topic? Do you have any strategies for that?

I would start with looking at their story grammar knowledge. If you could transcribe one of their narratives and look at what kind of story grammar it has, you might be surprised to see that their story grammar is not true story grammar. It is more content-related or more expository in nature. Then, I would work with them to develop story grammar that has a who, what, when, where, why, character, problem, setting, and evaluation. It might be that they really need some work on developing true story grammar versus just relying on expository text. After working on that, they might be able to shift topics better. But my hunch is that they're relying on expository text versus story grammar.

References

Audet, L. (2019). Linking Cognitive Processing, Psychosocial Development and Social Competency to Intervention for Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder Level 1 Severity. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interests Group pp.1-9

Audet, L. (2017). Communication interventions to assist in transitioning adolescents and adults with ASD beyond high school. ASHA Webinar.

Audet, L., Devine, M., Donnelly, K., Hamilton, J., McCloskey, M., Neal, B., & Springford, M. (2018). Perceptions of the needs of college students with ASD: An awakening for SLPs. E-poster presented at American Speech-Language-Hearing Association Annual Convention, Boston, MA.

Benson, J. D., & Sabbagh, M. A. (2017). Executive functioning helps children think about and learn about others’ mental states. In M. J. Hoskyn, G. Iarocci, & A. R. Young (Eds.), Executive functions in children’s everyday lives: A handbook for professionals in applied psychology (pp. 54–69). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Bodner, K. E., Engelhardt, C. R., Minshew, N. J., & Williams, D. L. (2015). Making inferences: Comprehension of physical causality, intentionality, and emotions in discourse by high-functioning older children, adolescents, and adults with autism. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 45, 2721–2733.

Campbell, J. M., Steinbrenner, J. D., & Scheil, K. (2018). The role of play in the social development of children with autism spectrum disorders. In R. Hawkins & L. Nabors (Eds.), Promoting prosocial behaviors in children through games and play: Making social-emotional learning fun (pp. 85–116). Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science Publishers.

McConnell, D. A., Chapman, L., Czajka, C. D., Jones, J. P., Ryker, K. D., & Wiggen, J. (2017). Instructional utility and learning efficacy of common active learning strategies. Journal of Geoscience Education, 65(4), 604–625.

Semrud-Clikeman, M., Walkowiak, J., Wilkinson, A., & Butcher, B. (2010). Executive functioning in children with Asperger syndrome, ADHD-combined type, ADHD-predominately inattentive type, and controls. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40, 1017–1027.

Citation

Audet, L. (2021). The Role of Executive Functions in Social Interaction. SpeechPathology.com, Article 20490. Available from www.speechpathology.com