Editor's Note: This text is a transcript of the course Reading Comprehension and the SLP: Foundational Understanding, presented by Angie Neal, MS, CCC-SLP.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Describe the difference between comprehension processes and comprehension products.

- Describe the currently accepted model for understanding language.

- Identify critical factors related to instruction in comprehension skills vs. comprehension strategies.

I'm really excited about this course on reading comprehension, mostly because many of the courses I've presented before are focused on decoding, phonological awareness, phonics, et cetera. But, we, as SLPs, do and know so much as it relates to reading comprehension. There is so much that we can contribute.

Why Is It Important for SLPs to be Knowledgeable About Reading Comprehension?

Oftentimes, we hear that SLPs don't teach reading, and to a certain extent, they're right. However, this is only to a certain extent because SLPs teach language across spoken and written modalities. Whether you call that reading or not may depend on the setting that you're in, but whether it's spoken or written, it is still all language. Really, it's just a shift in mindset that reading is not a naturally occurring process like language.

We are wired for language, and how we acquire language in the written modality is very much based on our proficiency with language in the oral modality. There are definitely differences between spoken and written codes. Syntax and vocabulary are less formal in oral than in the written modality, and in writing, there are exclamation marks and other conventions of print. But comprehension is built upon a foundation of language.

This is sometimes referred to as a "speech-to-print" approach or way of thinking. It's basically appreciating that when we start school, we are just mapping the sounds and words and sentence organization we've been speaking and hearing to print.

The Evidence Supporting the SLP Role in Reading Comprehension

Again, some say SLPs don't teach reading, and so I want to add one more caveat to that. If you are a school-based SLP, you are one of many professionals in the school building who support reading outcomes. We will circle back to that after we look at the evidence of the supporting role that SLPs play in reading comprehension and how it is intricately related to reading comprehension.

In fact, by third grade, children's language skills explain roughly 60% of the variances in their reading comprehension. Also, narratives, or the ability to tell or retell a story, are a bridge between oral language and written language because of the similarities between oral narratives and written language. That means we're considering vocabulary, grammatical structure such as elaborated noun phrases and subordination, as well as story structure (i.e., story grammar, character, setting, kickoff events, et cetera). What I particularly like about narratives is that they're clearly outlined in terms of what to expect at each developmental level.

There's a lot of research stating that by this age, they need to have this skill set related to narrative, and so on and so forth. So that makes it very easy for us as SLPs to identify specifically where the student is, and what skills they need to be taught.

In the world of language, many concepts are abstract and have moving targets, so to speak, for expectations. But narratives have an unusually clear set of expectations. Also, reading comprehension is a strong predictor of academic achievement. Directly targeting language skills can result in improvements in reading comprehension. Again, they're directly connected, which reinforces a language foundation for reading comprehension.

Finally, there are several specific studies that provide evidence supporting the SLP's role in comprehension. One study is of fourth-grade students who were provided with explicit vocabulary instruction. Results of the study showed significant positive effects not only on their vocabulary but also on reading comprehension.

As I stated earlier, whether it is spoken or written, it is still language. And the better we support language development, whether it's provided by us in special education, the special education teacher, the classroom teacher, the interventionist, or the school psychologist, the better we make those connections to language, the better our understanding of what the student's language needs are and what's necessary for them to comprehend, and how best to support instruction in those areas.

Other Professionals Who Support Reading

Returning to the other professionals mentioned earlier, let's discuss their roles and explore how we can collaborate effectively. First, let's consider school psychologists. Typically, they lead the MTSS or problem-solving team discussions and are responsible for assessing reading and reading comprehension. As speech-language pathologists, our involvement on this team is crucial due to our specialized knowledge of language. We can offer valuable insights through problem-solving approaches or comprehensive assessments. Our focus is on examining reading through a linguistic lens, considering syntax, morphology, phonological awareness, semantics, pragmatics, and narratives. This approach ensures accurate identification of needs and helps us establish clear goals for intervention.

Moving on to classroom teachers. They play a pivotal role in providing direct reading instruction from pre-K through 12th grade. Even though pre-K doesn't typically involve teaching reading per se, it lays the critical foundation for oral language development, which is fundamental for transitioning to print-based learning. Classroom teachers possess extensive knowledge of curricula, grade-level expectations, standards, and benchmarks for students' progress compared to their peers.

However, what remains unclear is the extent of information they receive regarding language during their teacher preparation programs or ongoing professional development. Notably, many teachers may not receive sufficient training in language-related areas. For instance, consider LETRS, an acronym for Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling, which provides valuable training for educators. The emphasis on the first letter of the acronym, "language," is crucial. LETRS is designed to impart essential knowledge about language to educators, making it a highly recommended resource for professional development discussions in your area.

Collaborating with classroom teachers is essential. They are at the forefront of gathering data that identifies challenges with grade-level assignments and assessments. As school-based SLPs, we rely heavily on this data to document adverse educational impacts accurately.

Next are reading interventionists. Their role is pivotal in providing targeted support for specific areas of weakness in students. As SLPs, we should collaborate closely with reading interventionists, especially in problem-solving scenarios where students are not progressing adequately or failing to close the gap with their same-age peers. Our role involves assisting in identifying appropriate targets for intervention, many of which likely have a language foundation. It's important to note that some intervention programs used by interventionists may adopt a one-size-fits-all approach or lack evidence of effectiveness.

Therefore, part of our responsibility is to examine the evidence presented in intervention manuals and ensure that the intervention aligns specifically with the student's needs. Delaying the addressing of specific needs only prolongs the time it takes to close the gap in skills, leaving students without vital information for longer periods.

Moving on to special education teachers. They play an important role in supporting reading. Collaboration between SLPs and special education teachers is paramount. While it may pose challenges due to time constraints, combining, sharing, and aligning goals is critical. By working collaboratively, we can address the linguistic underpinnings of reading and reading comprehension across different settings and perspectives. This concerted effort enhances our effectiveness and efficiency in closing the gap for students with diverse learning needs.

The National Reading Panel and Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA)

(20 U.S.C. § 6301, 2015)

To gain an understanding of the applicable laws in general education regarding reading comprehension, we need to discuss the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). Under ESSA, general education is guided by specific regulations distinct from those outlined in the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), which pertains to students with disabilities.

ESSA delineates the essential components of reading instruction, drawing from the findings of the National Reading Panel. This panel, a collaboration between the National Institute of Child Health and Development and the US Department of Education, conducted extensive research on how children learn to read and evaluated the effectiveness of various instructional methods.

The National Reading Panel's comprehensive review, encompassing 35 years of research and involving experts from diverse backgrounds, culminated in its 2000 findings. These findings emphasized that the most effective approach to reading instruction, inclusive of reading comprehension, entails explicit instruction in phonemic awareness, systematic phonics instruction, strategies to enhance vocabulary, developmentally appropriate language structure instruction encompassing morphology and syntax, as well as techniques to improve fluency and reading comprehension.

The emphasis on reading comprehension and fluency is indeed notable. Under ESSA, comprehensive literacy instruction hinges upon teachers' collaborative efforts in planning, instruction, assessment, and continuous professional development. This aspect of the law presents a significant opportunity for us to underscore the importance of providing collaboration and ongoing professional development related to the language underpinnings of reading comprehension, as mandated by federal law.

Given this, how can we support students and our general education colleagues by informing them about the foundational aspects of language for reading comprehension? How can we aid students and our general education peers in understanding the general language foundation for reading comprehension? How would you suggest accomplishing this through collaboration or professional learning opportunities?

Furthermore, ESSA mandates the use of valid and reliable assessments, which is particularly necessary when addressing concerns about reading comprehension. This requirement underscores the importance of data and diagnostic accuracy in identifying suspected weaknesses in reading comprehension.

What Do Alphabetic Reading Levels

Reveal About Reading Comprehension?

Let's examine three assessment tools or methods, and I'll let you decide on their validity and reliability. The first is alphabetic reading levels, where a teacher might assign a level to a student, such as "little Johnny is on level N," or set a goal for progress, like moving from level C to E.

Alphabetic reading levels primarily focus on the material rather than the individual student's strengths or needs. They lack evidence supporting measurable differences between levels (e.g., between N and M, or M and O). In essence, there isn't a clear and reliable distinction between these levels. Consequently, it is challenging for teachers to identify specific areas for improvement to help students progress to higher levels.

Furthermore, alphabetic reading levels provide little insight into students' strengths and weaknesses across critical areas such as phonological awareness, phonics, vocabulary, and language structures, including morphology and syntax. More importantly, studies indicate that instructional level placements in grades two through nine may not be beneficial; in fact, they could potentially hinder learning by limiting students' exposure to appropriately challenging material.

Oral reading fluency emerges as a more diagnostically accurate measure, boasting an impressive 80% correct classification rate. In contrast, the Fountas and Pinnell Benchmark Diagnostic Assessment System, which determines a student's alphabetic level, exhibits a significantly lower 54% accuracy rate in correct classification. As SLPs, we strive for an 80% sensitivity and specificity threshold, acknowledging that even then, there's a 20% margin for misclassification. A 54% accuracy rate is scarcely superior to chance, underscoring its limited diagnostic use.

What Does a Running Record

Reveal About Reading Comprehension?

Running records are another assessment tool. Often, educators provide running records as a form of data. They provide information on alphabetic reading levels, similar to what we discussed earlier. They also indicate accuracy levels, detailing omissions, errors, and substitutions in students' reading. However, they fail to address why accuracy may be affected. For instance, does the student struggle with vowel-controlled R words or multisyllabic words? Are they prone to substituting words based solely on the first letter?

Running records also assess fluency and the use of self-correction, which provides some valuable insights into students' self-monitoring skills. It will also provide information on what cues the student used to figure out a word, which we will discuss shortly. However, running records, like alphabetic reading levels, do not address students' skills in phonological awareness, phonics, vocabulary, morphology, syntax, and other areas crucial for comprehension. They fall short in answering the fundamental question: What specific areas do students need to learn or be taught to improve fluency and comprehension?

MSV/Three Cueing System

Next is the Three Cueing System, particularly MSV, which stands for meaning, structure, and visual cues. The MSV prompts students to consider whether the text makes sense, fits the storyline, sounds right, and matches the letters or pictures on the page.

However, none of these cues necessitate actual decoding of the words on the page. Instead, MSV directs the reader's attention away from essential alphabetic skills and phonemic awareness abilities, such as blending phonemes and pronouncing written words, which is necessary for decoding words of increasing length and complexity.

Therefore, what this indicates is that these three cues may actually help to explain why children begin struggling in third and fourth grade. If students have never learned how to decode words because they've been looking at the pictures and have been making a guess, then they're going to struggle to read text that has bigger words, fewer pictures, and more syntactically complex with harder vocabulary.

However, what's most concerning to me is that the strategies promoted by the three cue systems, particularly MSV, serve as a model for how poor readers approach text. Consider this: if you were to read something in another country's language without familiarity, you would likely rely heavily on visual cues, such as pictures, rather than decoding the words themselves.

Our goal is to cultivate skilled readers, and the true hallmark of a skilled reader is to not rely on any cues. In fact, a skilled reader can effortlessly read a list of unrelated words without context, which shows true proficiency in word recognition.

The Simple View of Reading (SVR, Gough & Tunmer, 1989)

I wouldn't be doing justice if I didn't touch upon the Simple View of Reading within Scarborough's Reading Rope before discussing The Active View. The Simple View of Reading, coined by Gough and Tunmer, states that reading comprehension results from the interaction between word recognition and language comprehension. It's essential to understand that reading comprehension can only occur when both sets of skills are present.

For instance, if you lack the ability to decode words but can comprehend the text when it's read aloud to you, would you achieve reading comprehension? No. (The equation would be zero times one, resulting in zero comprehension; see slide 16).

Likewise, if you can read the words but lack understanding of their meanings, would you achieve reading comprehension? No. Similarly, possessing only partial decoding and language comprehension skills would yield limited reading comprehension. In essence, a combination of both word recognition and language comprehension is needed to attain reading comprehension.

Scarborough's Reading Rope

Scarborough's Reading Rope serves to address the question: "What skills constitute word recognition and language comprehension?" This framework, introduced by Hollis Scarborough in 2001, extends upon the foundational work of Gough and Tunmer. Scarborough dissected the precise skills associated with each area, distinguishing lower strands for word recognition and upper strands for language comprehension.

Using the rope analogy, the intertwining of these skills shows the development of fluency and strong comprehension in reading. Understanding Scarborough's Reading Rope and the Simple View of Reading is important, particularly for SLPs, as they eliminate the guesswork for intervention.

If a student struggles with word recognition, formative assessments can be conducted in the three areas outlined in Scarborough's Reading Rope: phonemic awareness, phonics, and automatic word recognition. These assessments can be used to design an intervention or specialized educational program to target those skills specifically.

It's important to recognize that both the Simple View and Scarborough's Reading Rope underscore the necessity for interventions to be grounded in an understanding of the causes of reading difficulties. This understanding is rooted in how typically developing learners master reading skills.

I trust that this discussion is starting to show the significance of the language foundation in reading comprehension. It's imperative to recognize that when a student struggles with reading comprehension, the root cause may be poor word recognition. Therefore, our initial step involves examining word recognition skills, as they could be the barrier to proficient reading. Alternatively, the challenge might stem from underlying linguistic or language deficits.

Conditions such as language impairments or developmental language disorder are often linked to difficulties in word reading and comprehension. Notably, language deficits can impact both aspects of the Simple View of Reading or the strands of Scarborough's Reading Rope, highlighting the interconnectedness of language skills in the reading process.

I've frequently used the phrase, "A specific learning disability is simply a continuation of a language disability, a developmental language disorder," because it's language that is in the written form. Consequently, it's very rare to encounter a student with a language disorder who wouldn't go on to have reading difficulties.

This underscores the need for comprehensive assessments. It's insufficient for the SLP to conduct a language assessment, only for the school psychologist to address reading concerns a year later. IDEA mandates comprehensive assessments that encompass both language and reading domains. Even after a child acquires proficient decoding skills, our role in collaborating and supporting language remains critical. Language proficiency continues to determine comprehension or be an obstacle to comprehension.

Current Models of Language

Let's look at the evolution of language models. We are all familiar with the form, content, and use model, which originated in 1978. Subsequently, in 1983, the receptive-expressive model emerged. However, in 2006, research findings challenged the validity of the expressive and receptive explanation for language difficulties.

Current research indicates that oral and written language abilities, particularly during the school-age years, are best explained by a two-factor model. This model comprises the sound/word level and the sentence/discourse level, with memory playing a contributory role. Notably, there is no longer evidence to support the notion of a receptive-expressive language deficit. Our understanding of language has evolved based on evidence, revealing its multifaceted nature encompassing sound/word level, sentence/discourse level, and memory as contributing factors.

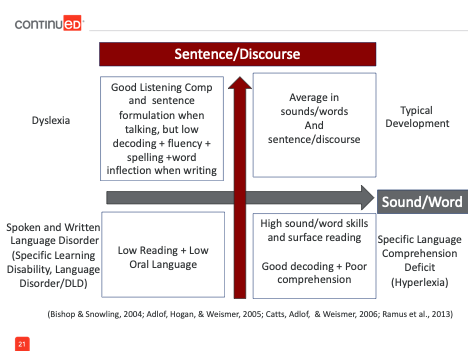

Quadrant Model

We can use the Quadrant Model to look at the classification of a disability (see Figure 1). By examining sound/word ability and sentence/discourse ability, we can lay out profiles of strengths and weaknesses that indicate the type of difficulty a student may experience. For instance, consider dyslexia. Students with dyslexia typically exhibit strong sentence/discourse abilities, enabling them to comprehend information when it's read aloud. However, they often struggle with sound/word level abilities, which can manifest as difficulties in decoding and recognizing written words. We can use this model to discern the type of difficulty.

Figure 1. Quadrant Model.

Implications for Comprehensive Assessment

This brings us back to the importance of comprehensive assessment. As outlined in the Code of Federal Regulations, evaluations must be sufficiently comprehensive to capture the nuances of a student's abilities and challenges. Given the strong correlation between language disabilities or developmental language disorder and later difficulties with reading, a comprehensive assessment is imperative.

Collaborating with school psychologists is crucial in conducting comprehensive evaluations. School psychologists play a pivotal role in assessing for specific learning disabilities, with listening comprehension and oral expression being integral components of the definition. This requirement has been a cornerstone of IDEA since its inception in 1975, and the body of research supporting it has continued to expand over the years. Remember, even the National Reading Panel came out just in 2000.

Let's look at their definitions of oral expression and listening comprehension. Oral expression refers to the ability to articulate wants, needs, thoughts, and ideas through appropriate syntax, grammar, semantics, and phonological structures. On the other hand, listening comprehension involves understanding the implications of explicit word meanings and sentences in spoken language.

Understanding the distinction between oral expression and listening comprehension, along with our evolving comprehension of language, helps explain why there may be discrepancies between assessments conducted by SLPs and school psychologists. It's important to note that while the school psychologist's assessment evaluates proficiency with academic language, the SLP's assessment focuses on fundamental communication abilities. As a result, our assessments are fundamentally examining different aspects of language proficiency.

Assessment: Comprehension Processes vs. Comprehension Products

Let's discuss the distinction between comprehension processes and comprehension products, as this differentiation carries significant implications for assessment and treatment. To illustrate this concept, consider your car. During its manufacturing, it underwent a series of processes or actions to become a functional vehicle. While you didn't witness every individual step or action, they were essential in producing a working car. However, if any part of this process is interrupted, faulty, or omitted, the outcome is a flawed product—a lemon, so to speak.

Comprehension Products

Comprehension products are observable outcomes—what we can see. This includes responses to comprehension questions, answers to multiple-choice questions, explanations to "why-do-you-think" inquiries, and the ability to construct an outline. However, it's essential to ask how they got there. What processes underlie them?

This distinction is particularly important because it prompts us to consider whether we are truly teaching comprehension or merely assessing it within our intervention and support frameworks.

Comprehension Processes

Comprehension processes are those things you can't see. You can't see making connections between prior knowledge and new information, recognizing inconsistencies or gaps in understanding, mentally visualizing the content when reading, and thinking about what will happen next in the text. So when we are reviewing students' work, specifically answers to comprehension questions, it's one thing to know if the answer was correct or not, but it's another thing to consider how they arrived at that answer. What specific processes interfered with obtaining a proficient product?

For instance, writing goals solely focused on WH questions overlooks the diverse nature of comprehension processes. Questions like "What is your favorite color?" differ significantly from math problems like "What is the product of 345 times 292?" It's imperative to shift our focus from writing goals for specific question types to understanding and addressing the underlying comprehension processes.

Assessment: What to Do First

In assessment, the first step when presented with a child experiencing difficulties is to ask, "Can the child accurately answer comprehension questions when the text is read aloud?" If the response is "yes, the student can respond accurately," according to the Simple View of Reading, we know the obstacle is with the words themselves. If we know the obstacle is word recognition, we need to look deeper and gather additional data on skills outlined in Scarborough's Reading Rope, such as phonemic awareness, phonics, and automatic word recognition.

If the child cannot answer the comprehension questions accurately, we must turn our attention to the other strands encompassed within language comprehension and Scarborough's Reading Rope. This includes assessing background knowledge, vocabulary, language structures (morphology and syntax), verbal reasoning, and literacy knowledge. However, there's another critical aspect to consider, which will be the focus of the remainder of this course.

The “Something Else:” Additional Factors Related to Reading Comprehension

We must consider the possibility of other contributing factors that may impact reading comprehension. Numerous studies have highlighted that challenges with decoding and listening comprehension persist even when these skills are at grade-appropriate levels. So, how do we discern the underlying obstacle? Here's where the "something else" comes into play.

These additional factors directly influence reading comprehension and may include comprehension strategies (or the lack thereof), difficulties with fluency, motivation, engagement, visual-spatial-perceptual skills/situation model/mental model, and executive function. While this list isn't exhaustive, it encapsulates the significant factors we'll focus on for the remainder of this course.

The Active View of Reading

This brings us to the Active View of Reading, which builds upon the foundation laid by the Simple View of Reading and Scarborough's Reading Rope. Developed by Duke and Cartwright, the Active View of Reading explicitly delineates all the elements contributing to reading comprehension, providing insights into potential causes of difficulty within, across, and beyond word recognition and language comprehension.

Unlike its predecessors, the Active View of Reading encompasses a comprehensive range of factors that influence reading. It acknowledges the significance of motivation and engagement, executive function skills, and strategy use—elements not explicitly addressed in the Simple View or the Reading Rope. Importantly, each of these constructs within the Active View model is amenable to instruction, meaning they can be taught or supported to enhance reading comprehension outcomes.

1. Comprehension Skills vs. Strategies

What's the difference between comprehension skills and strategies? Comprehension skills, as outlined in Scarborough's Reading Rope, encompass background knowledge, vocabulary, language structures, verbal reasoning, and literacy knowledge. These skills should become increasingly automatic over time, allowing individuals to employ them effortlessly. Consider how much language is embedded in those skills - language structures such as morphology and syntax, vocabulary acquisition, and verbal reasoning, which involves making inferences and predictions.

Comprehension strategies, on the other hand, are deliberate activities. They're goal-directed actions, and your goal is to control or modify your efforts to decode, to understand what you're reading, and to construct meaning out of the entire text. They are things we do purposefully. They may not be automatic until we are proficient readers, but they're all related to language.

When discussing comprehension strategies, it's important to acknowledge, especially when collaborating with teachers, that no comprehension strategy, absolutely none, can compensate for the inability to decode words. It's an indisputable fact. Regardless of how much time is dedicated to teaching strategies like identifying the main idea, summarizing, or making inferences, none of these tactics are effective if the fundamental skill of word recognition is lacking.

This underscores why strategy instruction is most effective and appropriate for students in fourth grade and beyond rather than those in third grade and below. While strategy instruction shouldn't be entirely disregarded for younger students, its effectiveness increases once students are proficient readers.

This helps explain why strategy instruction is most effective and suitable for students in fourth grade and beyond, as opposed to those in third grade and below. It's not to say that strategy instruction should be completely discounted for younger students, but its optimal application is for fourth graders and above, particularly once they have become proficient readers. It's also closely tied to the cognitive development of students in fourth grade and beyond. At this stage, their attention spans and memory capacities are notably higher and more robust compared to those of younger students.

In the lower grades, challenges with comprehension may not necessarily stem solely from decoding difficulties but rather from factors such as background knowledge and vocabulary. In fact, background knowledge and vocabulary play pivotal roles in determining reading outcomes, especially in the lower grades. You might initially assume that decoding is the primary issue, but consider this: if students lack understanding of terms like rural, suburban, and urban, and have never encountered urban environments despite living in rural areas, their comprehension can be significantly affected by their limited vocabulary and experiences.

Extensive scientific research underscores that teaching comprehension strategies can indeed enhance reading skills even in younger students. While it's most effective for fourth-grade students and above due to their refined skills and improved attention and memory, it remains valuable to integrate comprehension strategy instruction alongside other approaches for younger students.

I recently listened to an insightful podcast by the remarkable Dr. Tiffany Hogan, and she offered a brilliant metaphor for understanding the relationship between teaching decoding and reading comprehension. Often, people view it as a linear process, similar to a relay race, where you master one skill, pass it on, and move to the next. However, it's more like a parallel race, where you're developing decoding skills simultaneously with underlying language skills and strategies. This parallel approach ensures that when you reach the finish line, you possess all the necessary components for successful reading comprehension. Dr. Hogan's analogy beautifully captures this concept.

The National Reading Panel endorses several comprehension strategies. These include graphic organizers like Venn diagrams and charts, which help organize information. Question answering, where teachers pose questions to guide comprehension, is another effective strategy. Cooperative learning, where peers interact and discuss their learning, fosters intellectual discussion and improves reading comprehension.

Also, story structure, teaching narrative, story grammar marker, and instruction in the context of organization of stories improves comprehension of stories. The success in the treatment is more frequent and much better for poor, below-average readers because most good readers don't need the same instruction in narratives. Additionally, multiple strategy instruction at one time (i.e., doing multiple types of comprehension strategies all at once) is another effective strategy.

The National Reading Panel endorses comprehension monitoring because individuals with poor comprehension skills often struggle to monitor their understanding. This means they may read through a passage without comprehending it fully and fail to realize their lack of understanding. This is an important strategy for students.

Question generating emerges as the most scientifically supported comprehension strategy by the National Reading Panel. This technique involves reading a passage and then formulating questions about its content. Summarization, on the other hand, proves to be an effective strategy due to several reasons. It enhances memory retention of the material read, both in terms of free recall and answering questions. Moreover, summarization reduces cognitive load by condensing and synthesizing the main ideas in one's own words. Summarization techniques progress along a continuum, starting with basic structures like identifying beginning, middle, and end, first, next, then and progressing to more structured routines such as "somebody wanted, but, so, then," and advancing to complex forms focusing on main ideas, supporting details, and eliminating irrelevant information.

2. Fluency

Fluency, another component highlighted in the Active View of Reading, aligns with the Reading Rope model, where various skills intertwine to foster fluent reading and strong reading comprehension. Fluency, as depicted in the Reading Rope, hinges on three key aspects: accuracy (i.e., how precisely the text is read), automaticity (i.e., how quickly the text is read), and prosody (i.e., reading with appropriate expression, intonation, and phrasing). These elements collectively contribute to fluent reading and enhanced comprehension.

However, fluency is not an isolated skill despite often being treated as such. Frequently, IEP goals will state, "Will improve fluency from "X" number of words per minute to "X" number of words correct per minute. But fluency is not a standalone skill. It is intricately intertwined with reading skills. Consider this: if a fourth-grade student reading at a fourth-grade level is given an eighth-grade text, their fluency declines. Conversely, if that same student is presented with a second-grade level text, their fluency improves. This illustrates that fluency is influenced not only by word recognition but also by syntax and increasingly complex morphology. Thus, reading fluency reflects and is affected by language.

Fluency also reflects the student's grasp of language. Typically measured by words correct per minute, fluency serves as a powerful and accurate indicator of reading competence, aligning closely with comprehension. Over the past 25 years, theoretical and empirical research has affirmed its reliability and validity.

In contrast to the limitations of alphabetic reading levels, words correct per minute serves as a reliable metric for teachers. I often refer to it as the "canary in the coal mine" because difficulty with fluency is often the first sign that something is not working with a student's reading ability. From first to fifth grade, words correct per minute can effectively screen students for potential challenges and help diagnose underlying issues. Additionally, it serves as a valuable tool for progress monitoring, allowing teachers to assess the effectiveness of interventions and support strategies.

While words per minute is an important metric, we must also emphasize accuracy. Achieving at least 90% accuracy is essential for comprehending the text's meaning. Reflect on your own experiences reading; if you weren't at least 90% accurate in decoding the text, comprehending its meaning would have been challenging.

Moreover, there are certain things that fluency measures do not tell us about reading. They do not tell us about a reader's decoding skills, including phonemic awareness, phonics, and automatic word recognition. Additionally, fluency measures do not shed light on a reader's vocabulary, syntax, understanding of punctuation, or the visual aspects of context structure. Essentially, fluent readers must decode effortlessly to focus on comprehension. When readers expend cognitive energy on decoding and fluency, they have less capacity to comprehend the text's meaning.

The connection between fluency and motivation is pivotal. When reading feels like a tedious chore, characterized by slow and laborious effort, it's unlikely to foster motivation. As children progress through school, their reading requirements increase substantially. Consequently, if reading remains a struggle characterized by slow progress, meeting the grade-level reading demands becomes increasingly challenging.

3. Motivation and Engagement

Reading motivation includes the expectation that the material you're reading holds value and interest and promotes a desire to engage with the text actively. When you're genuinely interested in the content, you're more likely to remain focused, resist distractions, and immerse yourself in the reading experience. Conversely, if you've read material that didn't resonate with you, you're likely to be disengaged. Motivation and engagement are deeply intertwined with active self-regulation, involving the ability to monitor your focus, resist distractions, and stay engaged with the material. Interestingly, research suggests that motivation and engagement in reading predict reading proficiency beyond just word recognition and language comprehension. In essence, your willingness and desire to engage with the text can significantly influence your reading abilities.

4. Visual-Spatial-Perceptual Skills/Situational Model/Mental Imagery

Let's unpack the term "visual-spatial-perceptual skills," which might sound complex but is quite straightforward. This is the ability to create vivid mental images. Visual-spatial-perceptual skills, despite sounding complex, boil down to the ability to make mental pictures in your mind's eye. Research indicates a correlation between listening and reading comprehension and these skills, which are often assessed by school psychologists. In fact, non-verbal IQ measures in kindergarten were key predictors of eighth-grade reading comprehension. Nonverbal skills in first grade were predictive of fifth-grade reading comprehension.

This insight is particularly meaningful to me because, in my clinical experience, many students with developmental language disorder struggle notably with this skill. While they might identify objects easily in pictures (i.e., "Show me the dog"), they struggled to describe objects (i.e. "Tell me about your dog") because they didn't have that visual imagery.

Visual imagery or mental imagery is defined as the ability to sense, perceive, or experience sensations, sounds, sights, or tastes within your mind, even though they are not physically present. It's that ability to smell the fragrance of pine, taste the sweetness of sugar cookies, envision twinkling lights, or hear the jingling of bells while reading about winter holidays, regardless of the actual time of year. The ability to construct mental images is beneficial for listening comprehension and reading comprehension.

In terms of therapy targets, mental imagery holds significant importance for me. Why? Because it not only allows us to create mental movies while we read, visualizing the characters' actions as if they were in motion, thereby enhancing our overall understanding of the story like a movie, but it also allows us to make inferences or predictions about the characters and their actions.

Consider this: Authors don't explicitly describe every detail. Instead of writing, "The boy had one eyebrow up, and one eyebrow down, with his head tilted slightly to the right as he was thinking he was not sure which way he should go," they might write, "The boy had a quizzical look as he stared at the fork in the road." You have to be able to imagine what a 'quizzical look' looks like. Mental imagery assists with memory of the story and the story elements, even abstract ideas, metaphors, similes, other figurative language, et cetera.

Mental imagery serves this purpose as well. Consider a phrase like "His sadness was an ocean he struggled to swim across." Though it's figurative, it paints a vivid picture of the boy's deep emotional turmoil and the challenges he faced. Teaching mental imagery involves scaffolding and guidance. We start with basic elements such as categories, sizes, shapes, colors, backgrounds, locations, movements, functions, numbers, types, contents, materials, and parts. And that's just for single words.

Once we've mastered single-word imagery, we progress to more complex levels. We transition from single words to sentence imagery, paragraph imagery, and beyond. For instance, we may begin with a simple word like "dog" and then scaffold to build that image. We might describe it as a "Labrador retriever," specifying its color, size, and accessories like a pink collar. We imagine it as a small puppy chasing a squeaky orange ball thrown by a boy in a blue hat in a green grassy backyard. Instead of returning the ball, the dog indulges in chewing it. This process involves starting with a basic word, expanding it, and adding more to it. Eventually, we apply these skills to curricular texts.

5. Executive Function

Executive functions play a direct role in reading through cognitive flexibility, inhibitory control, working memory planning, and attentional control. Understanding how these skills contribute to reading comprehension is crucial. Reading demands that we concentrate on specific elements of the text (attentional control), build and maintain a situational model of the text while decoding (working memory), ignore distractions (inhibitory control), shift between reading and decoding or between figurative and literal language (cognitive flexibility), and plan and manage our reading progress effectively towards finishing the book.

As I mentioned earlier, executive function skills are responsive to intervention, and addressing them directly leads to improvements in reading, with the exception of working memory. While evidence supporting the improvement of working memory is limited, we can provide support through visual strategies and writing aids. When addressing executive function skills, especially in collaboration with special education teachers, we can significantly impact oral and written comprehension, including reading comprehension.

Let's consider some specific executive function skills. Cognitive flexibility involves the ability to shift between decoding meaning while reading and considering alternate meanings. This skill develops over time as vocabulary expands. Inhibitory control, particularly pertinent to autism, involves suppressing literal interpretations when they differ from intended meanings. For instance, "break a leg" does not mean to fracture a limb but a well-wishing phrase meaning "good luck." Working memory, as previously mentioned, is not readily trainable, but we can use various strategies to improve it. Working memory is pivotal for comprehension as it entails storing information while continuously integrating new data.

There are a few instructional implications to consider as I wrap up. An instructional implication to consider as we conclude is the concept of scooping, which supports working memory and mental imagery. Additionally, teaching figurative language is another instructional implication worth considering. In terms of fostering cognitive flexibility, educators can implement various strategies. For example, sorting a variety of items or words in different ways can be beneficial. Students can be given the same set of objects or cards and asked to sort them based on color, category, initial sound, function, location, and number of syllables, among other criteria. Encouraging students to explore numerous sorting methods can help enhance cognitive flexibility.

Questions and Answers

When working on visual-mental imagery, how does the child demonstrate that they can visualize or mentally see what you're telling them? I have tried to have the children draw the word or sentence, but it's not always successful.

I would say to do the opposite. Have them to you what to draw. Their words are drawing the picture. For example, if the word is "Christmas tree," they'll probably say, "Well, it has lots of angles," So, on a whiteboard, I would draw lots of angles. And they'll say, "No, no, no, that's not what I meant." And then maybe you'll finally get to, "Okay, it's a tall triangle." So then they may tell you to draw a big triangle. But would that look like a Christmas tree? No. So, their words help paint that picture of what their mind is actually seeing. This has been incredibly successful in order to get that first step level after we've gotten through category, size, function, and explaining all the different pieces and parts.

What do you mean by sentence and discourse level?

Sentence and discourse level is specific to syntax and discourse, and also related to narrative skills.

I have a student with a history of language disorder and she has been speech only. She now does not meet eligibility for language average scores. She's a great decoder but struggling with reading comprehension. Should the SLP still be on the team if she qualifies for specialized instruction for reading comprehension?

When you say that she has average scores, my first question would be, average scores on what assessment? Is it valid, and is it reliable? That would be my first question. My second question would be, especially if you're in the school setting, what does this look like in terms of her academic work, her curriculum?

So, my favorite thing has always been to look at their social studies tests. What types of questions is the student missing? Again, we want to make sure we ruled out difficulty with decoding. You have to rule that out first because if you can't decode anything or you can't comprehend anything, you can't read. But yes, there's definitely some value in keeping the SLP on the team to talk about those underlying language components, especially if they haven't been discovered yet.

References: See handout for a complete list.

Citation

Neal, A. (2024). Reading comprehension and the SLP: foundational understanding. SpeechPathology.com. Article 20653. Available at www.speechpathology.com