Editor’s Note: This text is a transcript of the course, Neurogenic Dysphagia in Older Adults with Motor Disorders, Part 1, presented by Jeanna Winchester, PhD.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- List the bodily systems involved in the swallow and describe their breakdown in dysphagia.

- Describe the relationship between the neurological and cognitive systems to the swallow and dysphagia.

- Describe the relationship between neurogenic dysphagia and hospital readmission rates.

I'm really honored to have this opportunity to speak with you today. What's really interesting about this course is that it began with something that is within my wheelhouse which is working with older adults with various types of neurodegenerative disorders and different types of neurogenic issues. Then, of course, the coronavirus outbreak occurred so I have added some information about that as well. I thought that was important to include because as we'll see, particularly with dysphagia, speech disorders, and with the aging population, there are going to be some long-term effects of having such significant acute respiratory distress occur in an aging population.

There is a lot going on right now and there's a lot of information out there. What we're going to try to do is put it together, present it in a cohesive way, and hopefully can take that information into everyday practice.

Dysphagia & Aspiration Risk

Dysphagia is so prevalent. It's the sequela of many chronic and complex conditions. We see it in stroke, in Parkinson's, and various types of dementia, which is really where my expertise comes in. I look at the systems surrounding neurogenic dysphagia but then my real expertise is looking at some of the dementia cases. We will be exploring Lewy body dementia in this course but I want to make sure to emphasize that there is a cognitive impairment component to almost every case study we're going to discuss. This cognitive component will be discussed throughout Parts 1 & 2 of the series.

Many studies have looked at the prevalence of dysphagia and the elderly community. Just being 55 years or older, there is a wear and tear that happens with the swallow and this is prevalent in the elderly. To add any sort of comorbidity or condition - it doesn't have to be a degenerative condition - even something like asthma can predispose the patient to a higher aspiration risk and more at-risk of dysphagia.

Generally, estimates show that there's a dramatic increase in community-dwelling adults that have conditions associated with dysphagia. That point is now an understatement. With the COVID-19 pandemic being a respiratory condition, inherently we are talking about the junction of the GI system, the respiratory system, our vocalizations, our neurology, our cognition, and all of that happens in the head and neck. Having such a dramatic viral outbreak occur in the respiratory system will have long-lasting effects on this dysphagia community.

Very likely, there is going to be an explosion of dysphagia-related cases following such a significant pandemic. That's because of aspiration pneumonia. Again, the very thing that these patients are at risk of is the contents penetrating the vocal cords, entering the respiratory tract, and taking up residence in the lungs. This is what a respiratory infection is, this is what a viral infection is and they aspirated the content. If they touched something on a surface that had the virus, then they touch their mouth, they have to swallow that. Perhaps they aspirated those contents, or it was from their nasal pharynx and there was a post-nasal drip of some sort. They absolutely aspirated those contents for the virus to make its way to the lobes of the lungs. So right away, we're in the ballpark of speech-language pathology expertise. This is the community that we need to be speaking to and we're likely to see a really large increase in aspiration pneumonia risk, aspiration risk, and possibly chronic dysphagia-related degeneration in many patients recovering from coronavirus.

In general, aspiration is a general mechanism and it is associated with inhalation. Let's not talk specifically about coronavirus - it's easy to talk about it because it's so prevalent right now. But it could be the flu, pneumonia, or reflux contents and they are aspirating very acidic gastric contents. Aspiration itself is a general mechanism of anything penetrating the laryngeal barrier that should protect the airway. When it crosses that barrier, it is aspiration. Aspiration actually occurs all the time. Even young and healthy individuals aspirate their oral secretions, particularly during sleep. We do it at various times throughout the day, although with activity and moving around, we are more likely to cough those out. In Part 2, I will talk about the effects of sedentary lifestyles, sarcopenia, malnutrition, and how the lack of activity can really drive this forward.

We also know that the amount of contents aspirated really makes a difference. For example, a small aspiration of oral contents, such as a little bit of saliva, may not do too much damage. But any amount of aspiration of acidic reflux coming from the stomach can burn the lungs. So, what gets aspirated is another important point, especially when we bring it back to COVID-19.

Aspiration Risk with COVID-19

Patients with COVID-19 are more likely to have thrush and other microbiomes in their oral pharyngeal and laryngeal cavities, especially if they were intubated or on any sort of artificial ventilation. As you return to more face-to-face contact with patients, or even in telehealth practice, be sure to review the oral health of the patient, especially if they have dentures, to see if there is evidence of thrush.

Chest wall capacity is going to be affected because of what COVID-19 does. The virus destroys the tissue of the lungs and the airways begin to collapse. This is kind of a really, really aggressive emphysema in an acute respiratory distress type of scenario.

Even after the virus is gone, these individuals are going to have a very difficult time with the scar tissue and being able to expand their lungs. The cough reflex will be affected because of the scarring and absolute exhaustion. All pharyngeal and laryngeal sensitivity and their motor responses will also be impacted.

Patients with COVID are going to have an additional burden of upper respiratory and lower respiratory disease. In addition to possibly any other comorbidities, this population is likely to have both acute asthma from the scarring, and possibly chronic asthma. For example, if they weren't diagnosed with COPD but they were on the path and were already deficient, this may put them into that final diagnosis or put them on that path.

There will be nutritional demands due to the virus. We know that the elderly already have an issue with malnutrition. Dysphagia brings malnutrition. Then a viral attack on the body can cause a significant loss of resources in the body, which we describe as malnutrition or electrolyte loss.

Simply being admitted to a SNF puts these individuals at risk. We know that community-acquired infections were already a problem. Now we have a pandemic that ravages communities, so just being in the community itself puts them at risk.

Finally, there are other super infections that are likely to become the topic of the fall and winter of 2020 and then going into 2021. As I said, it really depends on when you take this course. In the future, there will be many more topics coming out and I encourage you to continue to stay educated in the next few years and continue to look back at how the body reacts and responds as a person suffers through an acute respiratory infection. Individuals with COVID will now be at risk of something else such as MRSA, Cdiff, SIBO. These are already issues of community-acquired infections and rampant in populations that have dysphagia and in populations that are already at a high risk of aspiration.

I encourage you to keep this list of risks with you as you begin to re-enter this patient population and begin to treat the after-effects of this pandemic. You are likely to see, at a minimum, issues in this list and it'll probably be a much larger list as we go forward.

Bodily Systems Affected by Dysphagia

I want to review the bodily systems affected in dysphagia. I will review several but there are more. I co-authored a publication in 2015 that discusses these bodily systems of dysphagia which is available at: www.jwphdllc.com/jwphd-publications.

In the publication, we discussed that, at a minimum, there are five bodily systems affected by dysphagia: respiratory, neurological, cognitive, gastrointestinal and muscular.

In regards to the respiratory system, essentially, you have to hold your breath for 1-2 seconds to complete the swallow. A person who has difficulty with this (e.g., holding their breath), can aspirate in the middle of the swallow.

Neurological and cognitive systems are pretty intuitive, especially for SLPs. There is clearly a significant neurocognitive component to swallowing. The muscular component is fairly intuitive as well to this audience so I don’t want to spend much time reviewing it. But I do want to discuss how these systems interact, especially with the gastrointestinal system.

You may not have thought about this before, but the GI system begins in the pharynx. It is, obviously, supposed to move in one direction, going from the mouth all the way down. But any time something from the esophagus comes back into the pharynx, it is considered reflux, and that is dysphagia. That is a breakdown because the material should only move in one direction. That is very important to remember because reflux can be associated with medications, intubation, mechanical ventilation, sedentary lifestyle, etc. We may have patients who are likely to have more GERD. If they're in the hospital, they will probably be put on Pantoprazole or some other form of that to help with the GERD. But when they go home, they're going to have a massive reflux rebound. Their respiratory system will be compromised and they will have neurocognitive and muscular issues. With the reflux occurring, the acid may start to burn the lungs.

Together, these systems can really snowball out of control and that is because there's an evolving and accelerating effect of dysphagia-related decline across these bodily systems. The evolving nature of the decline can be described with a waterfall. At the top of the waterfall, we have the first inclinations of dysphagia and it just starts falling off the cliff. The below image is a waterfall that has been frozen. We see the effects of the waterfall, even with the freezing temperatures the water is still flowing.

Figure 1. Frozen waterfall metaphor.

But what I love about this photo is the evolving effect. You really see the effect of the waterfall on the surrounding area by seeing how it's frozen. All of the snow occurred because that water fell and the evolving nature of those effects has changed the landscape of the area. What I also love about this photo is how small we are by comparison and it really puts it in perspective that things can snowball out of control. There's an evolving and an accelerating effect, particularly now with this new respiratory-compromised population that we will be dealing with for the next number of years. We have to remember our place, but this is who we are relative to such an enormous problem. We can also have a very significant evolving and accelerating effect by managing this dysphagia.

Just to continue with the metaphor, if you were to put a dam at the top, it would stop the waterfall. Our dietary modifications and other compensatory effects can be the dam and we can stop the waterfall, that evolving and accelerating effect of dysphagia. If you learn anything from this series, I hope you take away this: the effects increase over time, and the devastation increases. But you can change it in the same way that we can change the power of these mighty rivers and these mighty waterfalls.

COVID-19 Affects the Respiratory System of Dysphagia

With anyone who might have any compromised respiratory component such as COPD, emphysema, chronic bronchitis, acute asthma, MERS, SARS, COVID-19, or even the flu, we are going to want to look at oral, pharyngeal, laryngeal, tracheal, bronchial, and lobar effects. We are going to want to have conversations with PT, OT, and respiratory therapy because, again, this is a snowball effect and can devastate many systems. Together, as an interdisciplinary team, we can really make a difference because of those long-term consequences of tissue scarring and dysphagia.

COVID-19 Affects the Neurological & Cognitive Systems of Dysphagia

COVID-19 is going to affect the neurological and cognitive systems of dysphagia minimally because of the fevers. There will be some apathy, aggression, defiance, and depression that will be specific to the elderly. There is also discussion of a possible encephalopathy with COVID-19 where the virus might be attacking the central nervous system itself. Some of the very first cases were misdiagnosed as Guillain-Barre which is an enigmatic neurological disorder that has inflammation and flu-like symptoms. It makes sense why it was misdiagnosed, but it might also be because there's a subset of COVID-19 patients that are actually having neurological encephalopathy. It will be important to continue to check on those findings.

Not all patients, but there may be a subset of the population that is actually having some brain hemorrhaging occur, either secondary to the virus or a version of the virus. At a minimum, if any patient has a cognitive impairment and they have a high fever, that high fever and inflammation exacerbate the cognitive impairment and the dementia. This will have an effect on long-term medical compliance.

That's the second point I hope you take away from this course and apply in your everyday practice. For the next few years, medical compliance will be very difficult and that may be something that you really have to work on with your patients. Follow up on those who are cognitively impaired. Are there telehealth ways that you can help these individuals adhere to their treatment without being right next to them in the room? That's something to consider as you look at how this might be impactful in your everyday practice.

I highly recommend that if you're working with patients who are over the age of 55, have a cognitive impairment, and coronavirus, make a referral to a neuropsychiatric physician or mental health nurse because there seems to be a neurological component. There is a broader availability of neuropsychiatrists via telehealth now. As of March 17th, they can see patients over video and teleconferencing in their homes and can assess things like apathy, aggression, and depression that might impede medical compliance. If you're going to give your patient a neurocompensatory technique, it's a good idea to check on them to see if they are actually able to do it or if they need a counselor or somebody to help them stay consistent with the treatments that you're recommending.

Defining Neurogenic Dysphagia

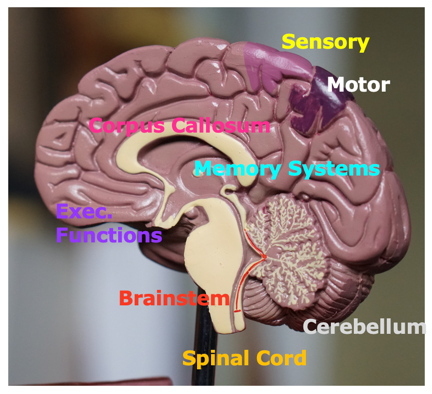

It all comes down to defining what neurogenic dysphagia is. Deglutition begins in the brainstem. Cranial nerves, the cerebellum, spinal cord, and cortex work together to execute the swallow. There's no specific one side of the cortex that is going to do this. One side may be dominant over the other which may have a little to do with handedness.

There's a temporal arrangement of all these structures - the respiratory system, the neurological, the cognitive systems – and they all have to work together. The respiratory system is responsible for breath-holding. The entire pharynx is going to have to rock forward so the GI system can open up in the form of the upper esophageal sphincter (it's naturally closed when the pharynx rocks forward). It pulls the upper esophageal sphincter open to allow the bolus to enter the GI system.

The neurological, muscular, and cognitive system should come together and coordinate all of the movements in order to close the larynx, close the vocal cords, retrovert the epiglottis, cover the airway, rock the whole thing forward, open the GI tract, and have the bolus safely transit into the GI component. But here's the tricky part. The upper esophageal sphincter has to close. The pharynx has to recuperate to its original respiratory configuration so you can passively breathe again. That recuperation component may be difficult for anyone with acute respiratory distress for any reason, but especially for COVID-19, for scarring, and for any of the case study conditions that will be discussed in this course. The reason it can be difficult for the pharynx to recuperate is because there's a lot of sensation and motor action happening. Your nervous system is constantly modifying it. For example, if something tastes bad, if it's salty, if it's hot, if you're just in a bad mood, then the swallow does something different because all of those things matter. Taste, pressure, temperature, nociceptive (i.e., touch), and general somatic stimuli (i.e., Do you have a headache? Is the dog barking? Is someone mowing the yard outside? Is someone talking to you and you're laughing in the middle eating?) are all things that happen at the same time. Your nervous system, cognitive system, muscular, respiratory and GI systems must all come together through the brainstem's central pattern generator to make this all happen. The brainstem is going to act like an extension of the cortex. It's going to modify our breath, our heart rate, and all those autonomic systems. It helps to make sure that everything comes together so the cortex can process it.

We are much more than our brain, we are really amazing neurological system, and there are many parts to that system that work. Many of them come together for the swallow, especially the reticular formation of the brainstem. It is a multiregional, multisensory coordinated experience and this portion of the brainstem modifies all those different autonomic and voluntary sensations. For example, let's say I'm laughing and I start to realize that I'm going to choke so I voluntarily cough. All of that is a very complex movement and if that sensation goes well, I keep eating and I continue my experience.

The swallow consists of the act itself, the neuromotor part, as well as our perception of the experience. Many individuals in long-term care and the elderly have very negative experiences because of what's happening with their dysphagia when they try to eat. This negative experience might cause them to choose to isolate themselves. The isolation can exacerbate the problem. It becomes a very multiregional, multisensory, highly coordinated experience.

The reticular formation in the brainstem controls a lot. The pontine pneumotaxic center is the center that controls breath rate. So, the same part of the brainstem that's controlling the swallow is regulating your breathing. It's also regulating all of the cranial nerves that are involved in the swallow: trigeminal, facial, glossopharyngeal, vagus, and hypoglossal. All of this has to come together in order for the swallow to happen. One thing I tell my medical students is that just because humans do it well doesn't mean it's an easy thing to do. It just means we're evolved to be really, really good at it.

Our brainstem has made it so that everything can be coordinated for us in an unconscious way. The brainstem is really the unconscious component of everything. It controls basic inspiratory and expiratory rhythms and depth. It can modify based on feedback and levels of carbon dioxide. For example, if you're laughing too hard, your brainstem is going to adjust based on how much oxygen and carbon dioxide you have. Think about how that is artificially affected if you're on mechanical ventilation. We don't know what the effects of it will be, but we're starting to see that a certain percentage of patients, not everybody (the majority of patients really need mechanical ventilation), but a small set of the population actually got worse on mechanical ventilation. It made the problem worse.

Why would that happen in that population? Could it be that the mechanical, artificial ventilation threw off their basic rhythms? It's hard to determine right now, but we are seeing some smaller subsets of patients where the ventilators weren't a good idea. Our own body is controlling our breathing and mechanical ventilation does artificially affect that. The body has to constantly adapt to the artificial levels of ventilation that are happening. So the question is if that stressed out that subset of patients?

The spinal nerves of the peripheral nervous system are located in the cervical and phrenic plexuses, which are behind the collarbones. The thoracic nerves are located at the superior portion of the sternum where the sternum meets the neck and the cervical portions of the head and neck. All of these are going to be affected in the face, larynx, tongue, diaphragm, shoulders, neck, the muscles in primary and secondary respiration, and even our abdominal muscles.

Not being able to exhale, not having control of the abdominal muscles, and having sedentary lifestyles can really affect the ability to hold the breath long enough to complete the swallow. If a person can't hold their breath long enough, they may try to breathe in the middle of the swallow and then end up aspirating.

All of these different systems – motor, sensory, neurological, etc. – come together. The below graphic shows the complexity of the swallow just in the neurological system alone.

Figure 2. Neurological system.

There are many different cognitive functions associated with the swallow: executive functions, memory systems, interhemispheric coordination, the brainstem, the cerebellum. I haven’t talked much about the cerebellum but something like chronic alcoholism would affect the cerebellum. There are many different diagnoses that can result in neurogenic dysphagia. The diagnosis can cause dysphagia or it can be exacerbated by dysphagia. In truth, what will likely happen is that the diagnosis may cause dysphagia, the dysphagia will exacerbate the diagnosis and then there is a terrible feedback loop. That is how dysphagia and neurogenic dysphagia can spiral out of control.

Case Study: Parkinson’s Disease

This brings us to our first case study. Parkinson's disease is a neurological disorder that is considered an upper motor disease. Upper motor diseases affect the central nervous system while lower motor affects the peripheral nervous system.

The substantia nigra of the subthalamic region of the thalamus sits in the deepest parts of the cortex between the brainstem and the cortex. The purpose of the thalamus, like Grand Central Station, is to send neuronal signals everywhere. In Parkinson’s, this part of the body is not making enough dopamine. That can happen for various reasons: chronic cocaine or heroin abuse, genetics (although that's only 2% of the population), exposure to a heavy metal like lead that might have poisoned their body, or they are just prone to a loss of dopamine later in life. For whatever reason, this imbalance between dopamine and acetylcholine manifests as the tremors that are characteristic of Parkinson's disease. These slow, writhing movements are called bradykinesia (“brady” means slow and “kinesia” means movement). It's important to break down that word because later I will compare this to Huntington's disease.

Parkinson's itself is associated with a form of Parkinsonian dementia. Because we are losing dopamine in Parkinson’s in the cortex, there are cognitive ramifications to changing any of the neurotransmitter levels. There are cognitive consequences of not having enough dopamine or taking L-DOPA as a substitute. So, Parkinson's has its own form of dementia.

This case study, from 2018, is looking at the effects of significant respiratory infections in Parkinson's patients. This is not specifically related to coronavirus because there is not much data at this time on Parkinson’s and COVID-19. However, there are a lot of lessons that we can learn in general for Parkinson's and significant serious respiratory infections that take them to the emergency room.

The researchers looked at admissions between January 2007-December 2013 and compared a number of clinical features, laboratory data, and various outcomes. They looked at patients who had these infections and then divided the group into those who had Parkinson's disease and those who did not.

Of the 1200 episodes of infection in Parkinson's patients and the 2400 other non-Parkinson's patients, it was found that the Parkinson's patients had fewer comorbidities. They also had a lower severity of infectious disease. This could be because Parkinson's patients are already cautionary, and so their behaviors are a bit different, especially if they have a caregiver or if they're in an assisted living facility. This would change their behavior and change the level of comorbidities in serious infections.

However, when they did have an infection that was serious, they stayed in the hospital much longer than the control group. What happened to them was much more serious, they stayed in the hospital much longer and they battled those effects for much longer compared to the control group. Additionally, the incidences of respiratory tract and urinary tract infections were higher in Parkinson's patients. The relationship of urinary tract infections to dysphagia or respiratory disease is that urinary tract infections will cause a fever. UTIs are contributing to some of the malnutrition and loss of electrolytes.

One of the more effective ways to diagnose and manage dysphagia, as well as aspiration, comes from imaging. So, how do we make the appropriate choice? I want to use some of my experience from PET, MRI, and X-rays as an example. When determining if you should choose the modified barium swallow (MBS) versus FEES for imaging, it really depends on what you're looking for. Let’s use an X-ray versus an MRI as an example. If I broke my arm, the bone can be seen in an X-ray and that's the equivalent of a modified barium swallow. The modified barium swallow is an X-ray. So, if it's quick and dirty and you can get something from the modified, that is the same thing with an X-ray. It’s quick and dirty, it's cheap, it's available, and many people can do it. If you can get information from the X-ray, go with the X-ray. However, there are things that an X-ray can't see by its very nature. That’s where an MRI comes in and FEES is like an MRI. If I tore a muscle or a ligament, if I have a neurological disorder or an issue with fluids, those things are not capable of being seen on an X-ray. In the swallow, there are some similar correlates to reflux that can't be seen on an X-ray because they're fluid or tissue-based. A FEES is going to be great for that. So it comes down to what you are looking for. If you need something a little more complex then use the FEES.

In a study by Tomita et al. (2018), there were a lot of choices between FEES versus modified barium swallow in Parkinson's. I bring that up specifically because Parkinson's disease, Huntington's, and many of these neurogenic dysphagia disorders that I'm talking about today have a lot of applications. I really recommend using these imaging studies because you can see many different aspects that are important. For example, evaluating chewing, transferring, aspiration, and total swallow time will relate to something significant like mortality. When these factors can be managed through imaging, we can improve measures of quality of life.

Case Study: Huntington’s Disease

Huntington's is very similar to Parkinson's but it's a different neurotransmitter. Huntington's is a genetic disorder that is very likely to happen in males in their mid-30s, especially if their grandfather had it and their father did not. It is fatal, and unfortunately, there is no treatment.

In Huntington’s, GABA is throwing off the balance between dopamine and acetylcholine. All three of these chemicals have to be in balance. A different part of the subthalamic region is affected in Huntington's disease. There are tremors but they are choreatic tremors which are wild, flailing tremors. Remember, in Parkinson’s we see the slow-writhing, slow-moving, shuffling feet resting tremor. Huntington’s may have a resting tremor but is more “wild”, and if a person specifically has choreatic movements, it’s going to be much wilder and flailing and erratic.

Unfortunately, there is no medical treatment. There are some dopamine receptor blockers but those are going to cause some other issues. In both Parkinson's and Huntington's there are issues with dysarthria and that is because anything that happens to the central nervous system is going to affect the peripheral nervous system. These individuals will have muscles that won't respond regardless of what they want to happen.

Similar to other forms of neurogenic decline, those with Huntington’s will have fear, anxiety, and a number of other cognitive-related issues. It will not necessarily follow a one-to-one fashion meaning, the cognitive decline will be at a different decline than the neurological decline. In fact, it's like dysphagia and will probably be circular. The neurological, the cognitive, and the swallow will deteriorate like a snowball, and they will circle back and affect each other and exacerbate each other.

In looking at these case studies, there is actually a lot that we can do. The topic itself is poorly explored in Huntington's disease because the population passes away very quickly, and it's harder on clinical trials in populations that know that there's nothing that can be done. But what they do see in the very few studies that have been published is that dysphagia should be assessed very, very early in patients with Huntington's and Parkinson's patients, especially in the presence of clinical markers. Additionally, frequent reassessments are necessary.

Longitudinal studies show that for OT, PT, and speech your interventions in swallowing and activity have significant quality of life improvement markers in these populations. Although collaborating with the physician and coordinating with the nurse practitioners and other medical teams is important for the pharmacological treatment of Huntington's, the rehab team is essential in the quality of life for Huntington's for rehabilitation, compensation, and caregiver training.

Case Study: Lewy Body Dementia

Lewy body dementia (LBD) is a term that encompasses both dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease with dementia. Lewy bodies are protein plaque that are building up, “body” means a tangle, a ball of hair, or a tumbleweed. If you have ever watched a western and the tumbleweed goes across the street, imagine if that tumbleweed was made up of a bad protein and that plaque body was being stuck in parts of the neurons. That's literally what's happening in LBD. There is this protein aggregate called the Lewy body that accumulates in the neural pathways of these patients. (As an aside, this disease has nothing to do with Parkinson's. You can have Lewy bodies by itself, you can have Parkinson's by itself, and you can have both. Lewy body dementia is an over-arching term to encompass all of those patients. This protein, called alpha-synuclein, accumulates on the tissue and eats away at it. It gets stuck between the neurons and stops dopamine transmission. Basically, the dopamine can't “jump” the synapse if there's is a giant protein tumbleweed in the way, and the plaque blocks the chemical from making it to the next neuron.

Currently, there are no disease-modifying drugs. This is similar to Alzheimer’s disease, even though Alzheimer’s has a different kind of plaque problem. In Parkinson's, Lewy body dementia, and Alzheimer's, the pharmacological interventions are trying to get the plaques to leave the brain. Under normal circumstances, the body naturally removes the plaque from the brain. But for some reason, especially with the elderly, the plaques are not leaving the body, they build up, and cause these forms of dementia.

With COVID-19 and LBD, there is a small amount of very preliminary evidence that silent aspiration risk is going to be huge in this population. This population, especially following tracheal penetration of intubation, pharyngeal retention and aspiration were present. However, patients with LBD are not likely to feel it, so they're not likely to complain of swallow dysfunction. You may have to assess and really utilize your clinical skills because this is a population that may not be able to feel it, which means they can't complain. So, your investigative skills and assessment skills as a clinician could be so important here.

Neurogenic Dysphagia & Return to Hospital Admission Rates

All of these factors associated with neurogenic dysphagia affect hospital admission rates. Being on an altered diet, presence of dysphagia, being sedentary, being isolated, risk of respiration, and/or being in the nursing home is going to predispose that individual to return to the hospital over and over again. Half of those patients are not likely to survive that over the course of 12 months. There's a very high mortality rate over 12 months. Now we must add the COVID-19 infection diagnosis to that list.

AHCA & the Coronavirus Pandemic

The American Healthcare Association (AHCA) has a wealth of information available. I want to highlight the FloridaHealth.gov/COVID-19 website. The AHCA really encourages you to go to that website because they believe it is the most accurate and up to date. You can also call 866-779-6121 or go to COVID-19@flhealth.gov if you have more questions. It’s recommended that when assessing these patients, you need to follow basic procedures regarding facemasks, isolation, precautions, and hand hygiene.

PPE is the word of the day for everyone, but if you work in a diagnostic facility where you are performing the MBS remember that there are appropriate respiratory collection procedures and you need to review your IPC practices.

Neurogenic Dysphagia & Return to Hospital Admission Rates

All of the factors discussed in this course are going to increase the likelihood of return-to-hospital admissions:

- Previous Hospital or SNF Admission

- COVID 19

- Neurogenic Condition

- Cognitive Decline Dx

- Speech/Language Impairment Dx

- Altered Mechanical Diet

- Use of Respirator/Ventilator, G/NG-Tube or Placement of Tracheostomy

- Co-morbid Respiratory-related Dysphagia Dxs

And just a reminder that G-tube placement and tracheostomy are just as biasing as a ventilator. If you have a patient that has a trach, was on a ventilator, and has a G-tube in place, a combination of those factors is very likely to snowball that patient out of control, especially if they're on a G-tube and they can't do PO trials of the different consistencies.

Management of Dysphagia in Acquired & Progressive Neurologic Conditions

The management of dysphagia typically involves looking at the cranial nerves. We want to do voluntary swallow tests. Be careful with doing test trials of ice and water because these patients are likely to have silent aspiration and are not likely to cough or complain. The voluntary cough may be impeded but you really need to assess it, so be careful with those test trials.

Questionnaires and other forms of self-report are not going to be very effective, again, because of that silent aspiration problem. How can they report it if they can't feel it? That’s why it is important to follow the gold standards of either doing an MDS or FEES.

Be sure to specifically look at weakness, spasticity, rigidity, hypo/hyperkinesia, ataxia/dysarthria, and other forms of discoordination. Additionally, dietary changes that you do can be so effective, and there are significant consequences if these measures are not put into place.

SLPs are integral members of the interdisciplinary team. Your follow up assessments and coordinating with the team help with monitoring patient progress.

Speech, language, cognition, and swallowing have many different neural substrates and they share that brainstem component, that unconscious autonomic component. This means that speech, language, and/or cognitive problems have a high likelihood of coexisting with dysphagia in patients with neurological disease.

The Role of OT in Management of Feeding & Swallowing Disorders

The role of OT in feeding and swallowing has been declining. I imagine that this is about to change because there's a broad need for OTs in dysphagia. The role of OT is still an ideal fit because there are many components that OTs can review during their sessions that complement what PT and speech are doing. OT can be an integral member because they can relate it to the other activities of daily living.

So as we look to broaden OT and their role in dysphagia, it may be that relationship to sarcopenia, malnutrition and other factors that I will address in Part 2. It’s with activities of daily living and quality of life where OTs can really add to what SLPs do in their therapy.

OTs are also going to be in the patient’s home and witnessing the patient's behaviors quite a bit more. So, as a referral source, SLPs should talk to their OTs more because they are able to observe the patient in their regular activities of daily living and may provide some insight that an SLP will not see in their structured therapy sessions. There is a fundamental difference in the way that OTs and SLPs perform therapy. What that OT observes can be so vital. If a person has silent aspiration but is not complaining to you, the OT may be able to see some other signs and provide a referral to you.

The Influence of PT on Oropharyngeal Dysphagia in Acute Stroke Patients

PT is extremely important in the management of dysphagia as well. On particular study compared a control group to a group of patients who received medical treatment for dysphagia plus physical therapy specifically related to muscles of the neck, head, and the upper respiratory airway. The researchers found that there was a significant improvement in those patients relative to other dysphagia patients who just had speech alone. After physical therapy, a coordinated treatment between speech and PT and OT, there were improvements across all variables in the one group compared to the other one who got speech alone.

These results show that an interdisciplinary program is not only true in theory, but it is absolutely true in practice. Another study also suggests that with stroke patients, when PT was brought in to do the dysphagia support and provide massage therapy and acupuncture, especially to the head, neck, collarbone and other components of the respiratory pathway, the patients who received acupuncture had improvements in dysphagia relative to those individuals who received speech alone.

In conclusion, neurogenic dysphagia has a really broad implication, even before this global pandemic broke out. But because of COVID-19, in the next few years, we're likely to see a real burst of patients because some of the chronic effects of this are going to be severe.

Questions & Answers

Have there been studies regarding aspiration of coronavirus and inhalation as a transmission source?

That is an incredible question. They have not yet been published. That's exactly what I have been looking for and it’s great that you're starting to make those connections because who knows what's going to happen. We do know, with other forms of respiratory infection, how easily it is to cross-contaminate, and some of those ventilators were getting split. Absolutely, I'm glad to see that you are making those connections because that could be a real issue and hopefully that'll start to become noticed soon.

References

Agency for Healthcare Administration (2020) Novel coronavirus update for health care facilities and providers. Agency for Healthcare Administration. Available from: https://ahca.myflorida.com/docs/Novel_Coronavirus_Update_for_Health_Care_Facilities_and_Providers.pdf

Ciucci, M., Hoffmeister, J., Wheeler-Hegland, K. (2019) Management of dysphagia in acquired and progressive neurologic conditions. Seminars in Speech and Language. 40(3), 203-212. DOI:10.1055/s-0039-1688981.

El-Tamawy, M.S., Darwish, M.H., El-Azizi, H.S., Abdelalim, Taha, S. (2015) The influence of physical therapy on oropharyngeal dysphagia in acute stroke patients. Egyptian Journal of Neurology, Psychiatry and Neurosurgery. 52(3), 201-205.

Komiya, K., Ishii, H., Kadota, J. (2015) Healthcare-associated pneumonia and aspiration pneumonia. Aging Disorders. 6(1), 27-37.

Larsson, V., Torisson, G., Bulow, M., Londos, E. (2017) Effects of carbonated liquid on swallowing dysfunction in dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson's disease and dementia. Clinical Interventions in Aging. 12,1215-1222. DOI: 10.2147/CIA.S140389.

Paul, S., D’Amico, M (2013) The role of occupational therapy in the management of feeding and swallowing disorders. New Zealand Journal of Occupational Therapy, 62(2), 27-31

Pizzorni, N., Pirola, F., Ciammola, A., Schindler, A. (2020) Management of dysphagia in Huntington’s disease: A descriptive review. Neurological Sciences. 153, 1.

Su, C., Kung, C., Chen, F., Cheng, H., Hsiao, S., Lai, Y., Huang, C., Tsai, N., Lu, C. (2018) Manifestations and outcomes of patients with Parkinson's disease and serious infection in the emergency department. BioMedical Research International, DOI:10.1155/2018/6014896

Xia, W., Zheng, Tang, Z. (2016) Does the addition of specific acupuncture to standard swallowing training improve outcomes in patients with dysphagia after stroke? A randomized controlled trial. Clinical Rehabilitation. 30(3), 237–246.

Winchester, J. & Winchester, C. (2015) Cognitive dysphagia and effectively managing the five systems. Perspective on Gerontology, Available from: www.jwphdllc.com/jwphd-publications.

Citation

Winchester, J. (2020). Neurogenic Dysphagia in Older Adults with Motor Disorders, Part 1. SpeechPathology.com, Article 20389. Retrieved from www.speechpathology.com