Editor's Note: This text is a transcript of the webinar, Management of Behaviors During Feeding and Swallowing Intervention, presented by Dr. Rhonda Mattingly, Ed.D, CCC-SLP.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- List three ways to analyze the communicative intent of a client's behavior around eating/drinking.

- Identify three types of communicative intent being presented through a client's behavior.

- Describe three methods for responding to a child's behavior related to eating/drinking.

Introduction

I hope that after completing this course, you have an appreciation for why behaviors occur on a whole-person level with feeding and swallowing. I also hope that you will understand the neurological implications and relationship between behaviors and feeding and swallowing.

Behavior

What is behavior? Behavior is basically the way a person acts. These are actions that may or may not fit into socially accepted norms. There are a few things to consider about behavior. We must keep in mind that social standards are going to vary across cultures. Not every culture is going to find one behavior tolerable or intolerable, it is going to vary. Also, we have the concept of neurodiversity which embraces the viewpoint that brain differences are normal variations and not deficits. It emphasizes the uniqueness of a person's individuality and cognitive functioning in that manner. Behavior can get a little "messy" because are many different norms and many different factors that should be considered.

Principles of Behavior

The first principle is that behavior is mostly learned. Secondly, behavior occurs for a reason. Behavior is not random. A behavior continues because of intentional or unintentional reinforcement and it ceases when it's ineffective.

Analyzing Behavior

How do we analyze behavior? We can first look at the ABC model of analysis, which stands for Antecedent, Behavior, and Consequence. The antecedent is basically the event, action, or circumstance that occurs before the behavior takes place. The behavior is simply the behavior itself. The consequence is the action or response that follows the behavior which will either reinforce or not reinforce that behavior from occurring again. This model of behavioral analysis is used in cognitive behavioral therapy, applied behavioral analysis, and verbal behavioral therapy. It can be very helpful in analyzing and determining what somebody is trying to communicate with their behavior.

Analyzing the Antecedent. Let's look at analyzing the antecedent with the following example in mind. Before doing that, consider the following example. Most of us have probably run a stop sign or stop light at some point, whether it was inadvertent or on purpose. Running the stop sign is our behavior. What is the antecedent? What were the circumstances around the behavior? You were driving a car. Who was there? You were there. What was happening just prior to running the stop sign? You were motoring down the road with your car. What was the environment? It was the car. If the behavior's reoccurring, what is the usual location? If you've done this before, was it always at this particular stoplight, or is it at all stoplights? When has it previously happened? Was it when you were in a hurry or when you didn't see a police officer sitting there? You are looking at what preceded that behavior. In this example, it's breaking a traffic law.

Describe the Behavior. Next, we look at the actual behavior. When we're looking at an actual behavior during this analysis process, we're going to describe just the facts. I say "just" because it would be really easy to say, "Oh, Bob ran the stoplight. He's a really bad person. He's a lawbreaker." But if we start making judgments and assumptions, then we're not focusing on that behavior anymore and that impacts how we deal with that behavior or help manage that behavior.

Acknowledging the Consequences. This is when you describe the response to that behavior. You determine whether the response will increase the likelihood of the behavior recurring and determine whether the response will decrease the likelihood of the behavior recurring.

Back to our stoplight example. You run the stoplight and maybe it's a stoplight that you've run many times. Maybe you do this because it's a stoplight that is too long, there's nobody around, or the police are not around at that particular stoplight very much. That's your behavior as far as stoplight goes.

Looking at the consequences, what was the response or the consequence to that behavior? Let's say one day you ran that stoplight, there was a police officer there and you got a pretty hefty ticket. At that point, is that consequence going to increase or decrease the likelihood of that behavior occurring again? Most likely, a big ticket is most likely going to deter most people from doing it again. However, if you find you can run that stoplight every week and never get caught or never get a ticket, then that may actually increase the likelihood of that behavior recurring.

So, we have to look at the consequence as to how much it is reinforcing or decreasing the likelihood of a behavior to occur.

Types of Reinforcement

Positive reinforcement is when we add something or give something that makes it more likely that a behavior recurs.

Negative reinforcement is when we take something away that increases the likelihood of the behavior. For example, if something is unpleasant and I take you out of that situation or take that negative stimulus away, that is going to reinforce that your behavior will occur again because it's worked. I've taken something away that you didn't want to have to deal with.

Punishment is kind of in between positive and negative reinforcement. Basically, you're getting something or something's being taken away, but it's in a negative connotation. You are paying a cost for it to some degree and it's going to probably decrease the likelihood of that occurring again.

Extinction is when you remove a reinforcement that's been continually given and thereby the behavior begins to go away and is ultimately extinguished because you're no longer reinforcing it in the way you've done before. Keep in mind though, that extinction is not permanent. It can be long-lasting, but if you begin to regive that type of reinforcement that was making that behavior more likely to occur, then whatever you've extinguished can come back.

Behavior as Communication

According to the literature, a person can communicate four different things with behavior:

- I want attention

- I want access to something

- I want to avoid something

- An automatic response – It's happened so many times before and therefore I'm on "auto-pilot"

Meet TB (Case Study)

Let's meet TB, the subject of our case study. He is three years and 11 months old. He was referred for a feeding and swallowing evaluation due to a really restricted diet and frequent food refusal. His medical history includes a term birth, vaginal delivery, and no complications. Current health indicates that he's had some frequent constipation over the past six months, but not prior to that. His developmental history shows gross and fine motor development were within normal limits and his speech and language were within normal limits. Socially, he lives with his mom and dad. His parents both work outside of the home and TB goes to preschool two days per week. When he's not in preschool, he's cared for by his maternal grandparents three days per week and they do live very close to him. So, he has a lot of support.

I'm not sure how many of you work with children with feeding and swallowing disorders, but he is a child who you would look at and think, "Wow, I wonder why he has feeding and swallowing problems." The point is that, historically, a lot of the children that I've worked with have had pretty complex medical backgrounds and it makes sense. But, this child on the surface looks like he would be fairly easy to work with.

Nutritional Profile

Let's look at his nutritional profile. He eats glazed donuts, one kind of mac and cheese, pancakes with syrup and one kind of white bread, sliced. He will eat chicken nuggets and two kinds of deli-sliced turkey. He drinks milk, chocolate milk one time per week, and vanilla yogurt. He eats applesauce and pears without the peel. He eats French fries - but only one kind - and baked potatoes with butter.

This is an extremely limited diet for a child, especially for a child who is three years, 11 months and typically developing in terms of gross, fine motor and language. So, this is a real issue for him to have this kind of limitation.

Oral Motor Exam

His oral motor examination showed that his hard palate was slightly high. His soft palate was symmetrical and elevated just fine. His tongue was symmetrical and his tone appeared within normal limits. He could elevate and lateralize, and his range of motion was within normal limits. Lips were symmetrical, tone was within normal limits, and he maintained a closed posture at rest. Range of motion was, again, within normal limits. Cheeks were symmetrical, tone was within normal limits. Mandible was symmetrical. There was a little bit of effort when he performed lingual mandibular dissociation. So, if he had to move his tongue independently of his jaw, he could do it but at times there was some effort depending on the task. Dentition was natural and in good condition. He did have a hyperactive gag reflex and intermittently appeared to have some reduced breath support. But, again, he did not have a terribly involved oral motor examination.

Behavioral Observations

Consistent behaviors. When TB arrived at therapy, his utterances increased from the time he arrived to when he visualized food in the therapy session. So, if we had food sitting on the counter, he would automatically begin increasing his utterances when he saw the food. Verbalizations increased further as food items were presented, and he was a very verbal child with rich language. So, when the food came out, he would start to tell stories and jokes.

When his grandparents accompanied TB to therapy, he would frequently get up and sit on his grandfather's lap when non-preferred foods were presented. When his parents suggest new food items at home, TB refuses and cries if they encourage him more than one time. If they offer him one time, he's okay and will just say, "No." If they don't stop at one time, then he gets upset and cries.

When attending parties and preschool events, he refuses pretty much all food and liquid items and his mom pretty consistently has to pack preferred food items for him to take.

Inconsistent behaviors. He will throw game pieces, food, or other therapy items that are in the room. He gets up from the table and moves around the room despite his mom saying, "Come and sit down."

What's interesting about this is that he was very cooperative in many ways and it was really atypical for him to get up and throw game pieces, et cetera during the session. He typically used that language to keep control and would get in his grandfather's lap. So, these inconsistent movements are referring to those times when he was moving all over the place, not just sitting on Grandpa's lap.

Analysis

Let's look at some of TB's behaviors from an ABC model perspective. The first behavior I wanted to look at was his immediate increase in talking, storytelling, and asking questions. There was a huge increase in verbal utterances using all the language he had at his disposal. This behavior occurred when non-preferred food items were presented in the therapy session. That is the antecedent. As I said, he did increase talking even when he just saw the foods, but as the foods were presented in actual therapy, verbalizations increased even further.

The consequence, or the response, to this action was the grandparents laughing or commenting on how smart or how funny he was. Additionally, Mom would redirect and Dad would instruct TB to pay attention.

If we think back to the different types of reinforcement discussed earlier, the grandparents were positively reinforcing TB by giving him something that helps the behavior to occur again. When TB is talking and storytelling and asking questions, and Grandma and Grandpa are laughing and telling him how smart he is, he's really able to avoid those food items. Plus, he's also getting attention. Whether it was inadvertent or on purpose, he certainly is achieving his goal. With their laughter, they are helping him escape from the food items and giving him attention, so he's much more likely to do that behavior again.

Moving on to his mom redirecting him. TB really wants to avoid these food items. He may or may not be going for the attention with his grandparents but he is definitely wanting to avoid the food items. What kind of reinforcement is his mom providing with her redirection? She is positively reinforcing TB's behavior. He wants to avoid the food items. So, when she's redirecting, even though he is being told to get back on task, he's still achieving his goal of avoiding interacting with the foods and trying the foods. In fact, redirection is a positive reinforcer in most cases. With this mom, a lot of times when she redirected TB, she would allow him big breaks from the therapy session.

The second behavior is, "When non-preferred foods are offered at home, TB will typically say "no" if he doesn't want to try them." However, if the parents offer it more than one time, he'll really begin to cry and become upset. The antecedent to that behavior is the non-preferred food items offered in his home. The consequence of that behavior is that Mom stops offering the food once TB cries and Dad continues to offer the food, but reports becoming frustrated and ceasing to offer anything else.

What type of reinforcement is Mom providing when she stops offering the foods when TB cries? Is it going to be more likely that he does this again because she's positively reinforcing? Is she negatively reinforcing? Is she punishing or is it extinction? If we think about it, TB doesn't want to be asked more than one time for this food item. His mom completely stops asking after that first time, so she is basically allowing him to avoid the new food items that are offered by taking away her request. She's no longer requesting that he do that. She is negatively reinforcing the behavior by taking something away. She's not asking him anymore and that's probably going to increase the likelihood that he's going to do that again.

That particular behavior can be looked at in a number of different ways. But the main point is to recognize the intent of the behaviors he's showing. We would all agree that he is avoiding the food items, so when his mom just stops after that first offering, she is really reinforcing that he doesn't have to try that food.

What kind of reinforcement is TB's dad providing when he continues to get frustrated? If TB doesn't want the food, Dad will continue a little while but he gets frustrated and then he stops. The dad is negatively reinforcing TB because he does persist in asking. But then he gets frustrated and stops. So, TB learned that if I don't want those food items, I can begin to cry. I can begin to have this behavioral response and even though my dad will push for a little bit longer, he gets frustrated and ultimately stops, and I ultimately avoid having to try that food.

The last behavior to analyze is TB suddenly throwing game pieces, knocking the game off the table, and knocking other non-food items off the table. We could be doing something that wasn't even about eating and he would throw the things off the table or get up and move around the room a lot. But this only happened when TB's mom brought him to his appointment, which was interesting. The antecedent to the behavior is non-preferred and/or preferred food items presented during turn-taking. Within that task, we would do a lot of socially driven things. We'd also be doing other activities that were not necessarily about eating, such as playing games. During those activities, this same behavior would happen. So, the antecedent was us being in therapy and there are some preferred foods and non-preferred foods around. But ultimately this child, who's typically compliant and uses a lot of verbal and language to avoid, is now having this big outburst. When thinking about the antecedent, I have to look around and see what's going on. Who's in the room? Has this happened before? Yes, it has happened before and Mom was in the room every single time it happened. The consequence, in this case, was Mom redirecting and instructing TB to pick up the items. Again, this is positive reinforcement.

If you recall, earlier I said that most behavior is learned. I also said that the behavior will extinguish, but it can come back. What I want to point out in this situation is that with this behavior, we had to dig a little further and look through all of our antecedents to figure out that it was always when his mom brought him that he threw things. It's repeated and it was a certain day of the week too. Thinking back to his food and drink items, he only gets chocolate milk one time a week. His mom and I realized that this very atypical behavior for him occurred on the days he had chocolate milk before he had therapy. My point is that his response was not necessarily a learned response. This was a response because the child had some intolerance to some level of this chocolate milk. We also realized that if he didn't get the chocolate milk, we didn't see those behaviors.

I want to point that out because I worry a lot about children with feeding problems in therapy. If we are simply looking at their behavior and saying, "Oh, he's throwing game pieces and he's knocking the game off the table," without really considering why, then we may try to punish, extinguish, or use positive/negative reinforcement without really appreciating that there is actually a much deeper reason that the behavior is happening. He is actually trying to communicate that his body is not able to tolerate that food item.

I did end up referring TB for an allergy test and other testing to figure out what was going on with him. He did not seem to have anything going on, but allergy testing is only about 50% accurate. The best way to figure out what somebody's intolerant to or allergic to in terms of food is to do an elimination diet. In doing that, we did figure out that TB had multiple foods to which he was intolerant, although not necessarily allergic. Again, it is very important to appreciate that behavior can be learned. It's not random. It's occurring for a reason, but that reason can be communication - I want attention, I want access, I want to avoid. But when I get to that automatic one, it can be because there's something underlying and that's why we always have to dig as far as we can to figure out why somebody is doing something, especially when it seems so atypical.

Is TB a "Bad" Kid?

TB's behavior doesn't "fit" social norms, at least in our area. Social norms in our area are that you eat much more than that and there is a lot more diversity in what you eat. You go to birthday parties and you eat what's offered, for the most part. His behavior doesn't fit the social norms and it's resulting in limited nutritional intake.

His behavior's impacting and is impacted by his family and social interaction. But, he's not a bad kid. He has some behaviors which are mostly avoiding non-preferred food items. We also know that some of his behaviors are for a very good reason in that he is intolerant to many food additives and other items.

He is trying to avoid something that, in his brain, is unsafe. In his brain, he feels that this is unsafe and it's unpleasant. We have to understand the perception that he has, which is this food is unsafe, it's non-preferred, and it's dangerous to me. That perception is going to impact everything. It's going to impact how his feeding develops, how he feels about food and his interaction with his family.

Feeding and Swallowing Development and Disorder

To be able to discuss how multiple intolerances to food items and additives impact TB and his feeding, we have to look at how feeding and swallowing develop. Feeding development is based on multiple components. It's based on gross and fine motor development, such as postural stability and how do I hold myself up against gravity? It's based on sensory experiences, such as smell, taste vestibular, proprioceptive, tactile, interoception, and visual-auditory. Feeding and swallowing are also based on physical and physiological readiness such as breathing, digestion, and having structural integrity in order to eat and drink. The final important component is this concept of social and emotional interaction and how all of that comes into play. When anything goes wrong within some or all of these areas, that will impact a child's feeding development and relationship with food.

Feeding Progression and Motor Skills

Typically, this is broken down into stages. Stage I is a period of physiological flexion and primarily reflexive activity. You move into extension and start to get head and neck control. If you're familiar with feeding development, this is referring to early infancy, when the infant learns to suckle at birth, and then sucking starts around four to six months.

Stage two is when independent sitting starts to emerge. Your toys and hands are coming to your mouth, there is active lip closure, sucking, and munching patterns. At times, most children are introduced to liquids and puree/cereal. Again, this is about six to seven months of age.

Stage three is when we start to see crawling, reciprocal motion is beginning, and the infant is getting a pincer grasp. Additionally, some lingual lateralization and a vertical chewing pattern have emerged. This is starting to emerge around nine to ten months.

In Stage four we start to see walking and the ability to eat most foods. A vertical and diagonal chewing pattern is present and rotary chewing is emerging. A lot of different foods are introduced at this stage.

The point in sharing these stages is to appreciate that the motor piece is what's making these things possible. As my body begins to have more ability to do these movements, it gives my mouth and tongue, etc. more ability to have a relationship with food and to develop. Therefore, if I'm two years old and I'm not walking yet, that will impact my feeding progression. Again, there is a very close relationship between motor development and feeding progression. Many of the children that you see on your caseload will not have typical motor development so we can't expect them to have typical feeding progression either.

Feeding Progression & Physical/Physiological Components

Feeding development is also closely related to physical and physiological components. We need physiological stability to eat and drink. We need a functioning respiratory system, adequate muscle tone, and midline movements. We also need to be in a behavioral state that allows us to alert and maintain that state. Again, a lot of the children that we see in therapy will have had some compromised physiological status. They'll have compromised motoric ability and compromised behavioral state. If these children are also trying to eat, take in nutrition, and their status is not great in these areas, then that will impact how they perceive food and how they behave about food.

Sensory Function

Sensory function cannot be underestimated. This is a child's experience with food and liquid through smell, taste, feel, sight, sound, and balance. This is also how the child's head is moving in relation to chewing, their self-awareness, and where their body is in space.

There is a concept called interoception which is our awareness of the internal workings of our body, such as our respiratory system and our heartbeat. It's also about hunger and satiation. Think about children on your caseload who have a premature history or a history of not getting to choose how much food they're taking in. Think about premature infants in the NICU. Everything is determined for them based on what the doctor and the dietician say their needs are for neurological development, weight gain, etc. These infants are on a schedule, they get "X" amount of ccs per three hours or per four hours. It's not necessarily about when the infant is cueing it should be. When infants and children are dependent on G tubes, their hunger and satiation have been altered. They have been fed at times when they were not hungry. They have been fed past satiation, in many instances. And, certainly, their behaviors around that are going to be evident as you're working with them in therapy. Again, sensory function cannot be underestimated when it comes to the impact on feeding development.

Feeding Progression and Social-Emotional

Feeding is a reciprocal relationship between the parent and child. The attachment that is formed around feeding is supported when the parent is following their infant's signals relating to feeding. For example, the baby cries, Mom or Dad hears that and they feed the infant. The infant begins to stop sucking or shows signs that they don't want to keep going, and the parent respects that sign by stopping the feeding.

Individuation can only occur after attachment develops. For example, I can maintain myself within my environment and when I do that, I can also begin to attach to those people in my environment if I'm an infant or a child. That comes from, "I'm getting my needs met. My mom and dad are reading that I'm hungry. My mom and dad are stopping when I'm no longer hungry and therefore I have a great foundation for going out and becoming my own little individual for exploring, finding new ways to interact with food, and interact with all these different things." So, feeding progression is very closely related to social-emotional development. It's that idea of feeling safe because my parents are meeting my needs. Therefore, I can go out and be a little more adventurous now. With a lot of the children that we see, this is not the case and we start to see behaviors because parents get a little stressed out which can impact further feeding progression.

Components of Responsive Feeding Interventions-Parent Actions

Let's look at the components of responsive feeding interventions in the context of feeding development. This is an actual intervention approach for working with parents of children with feeding problems. It's also a very natural part of what we want to see in feeding progression.

We want parents to recognize and acknowledge the infant's and child's hunger and satiation. We don't want them to use food to soothe an infant if they're not hungry because that's not respecting that whole hunger-satiation cycle. We want them to introduce complementary foods in a timely manner and to provide a diverse and healthy diet. We want parents to introduce viscosities that are developmentally appropriate. If a child does not have the developmental appropriateness for a certain viscosity, then we don't want to give that to them. We also want parents to provide an environment that supports interaction without distractions and in a structured manner.

These are the things that we want to see in typical feeding development as well. We want parents who are attentive to the child or infant while they're feeding them. We want an interaction going on between the child and the parent and we don't want it to be skewed with a ton of distractions. We don't want feeding time to constantly be in front of the television, for example. We want it to be a structured, typical relationship in a good, solid environment.

With almost every child that I have seen for feeding therapy, some part of this feeding progression is altered. It might be a motor or a physiologic response. Maybe the digestive system isn't working. It can be an interaction among many different things because when these issues start to crop up, you will also start to see changes in their social and emotional development or their sensory experience. These components interact and create how that child feels about food and progression through the stages.

Swallowing

Swallowing is important to address because it's a very complex task. I've talked about children feeling safe or unsafe, and swallowing can be very frightening and/or dangerous if you don't do it well.

Swallowing is a volitional and reflexive activity that involves more than thirty nerves and muscles. Altered structures, function, or coordination can result in dysphasia. Disordered feeding may or may not include a swallowing problem, but swallowing problems are going to impact feeding. If a child is aspirating everything that is thin then their feeding progression is going to be altered. Somebody's going to put the child on thickened liquids and then they will not have a typical feeding progression.

Finally, the consequences of aspiration vary but can result in pneumonia. Therefore, we have to think about this with children. Children have an idea about how they feel and that is going to either propel them to do something further or not. If a child has swallowing issues, is frequently ill, and gets pneumonia, that's going to impact how they feel about food, even when they're allowed to have food.

We also have to think about behaviors in relation to children with feeding and swallowing problems. We need to consider what a feeding disorder is. The definition, according to Goday et al., 2019, is impaired oral intake that's not age-appropriate and is associated with medical, nutritional, feeding skills, and/or psychosocial dysfunction. This is a good definition, however, I would change the wording of "age appropriate" to "developmentally appropriate". So, when somebody has an impaired oral intake that's not developmentally appropriate and is associated with medical, nutritional, feeding skill,s or psychosocial dysfunction, then that is considered to be a feeding disorder. This is different than dysphagia. Dysphagia is a disruption to the swallow sequence that results in compromise to the safety, efficiency, or adequacy of nutritional intake.

Factors Influencing Feeding & Swallowing

People you see for feeding therapy or swallowing therapy come to you because there's a disorder or a disruption in some aspect of feeding and or swallowing. The question we have to ask is "why?" What's the antecedent to that disorder or disruption? What are some of the factors that influence feeding and swallowing?

Medical and genetic diagnoses impact feeding and swallowing. There are so many children who are born premature and when that happens, they are much more susceptible to respiratory complications, congenital heart issues, necrotizing enterocolitis, et cetera. Those medical diagnoses are going to impact that infant on so many levels. Potentially, it makes them unsafe for swallowing but a medical diagnosis of prematurity can result in respiratory compromise.

It can also impact the child's physiological status or motor status. It's definitely going to impact the child from a satiation-hunger standpoint. It's also going to impact the child in terms of the relationship with their parent, because the parent may not get to feed them as they normally would.

Developmental delays can influence feeding and swallowing, as can sensory impairments. If a child can't stand the way that something wet feels on their hands, it's unlikely that they are going to be able to interact with it with their mouth, tongue, or lips.

Social-emotional issues can influence feeding and swallowing. Certainly, some atypical social-emotional relationships can influence feeding and swallowing. Structural anomalies can definitely impact feeding and swallowing, particularly when they're not recognized and someone is trying to encourage you to eat and drink, and you're really not comfortable with that.

There is a multitude of other factors that also influence feeding and swallowing. Feeding is so complex, and swallowing is so complex, that any of these things alone can impact negatively. However, you can also appreciate the fact that these often coexist.

For example, a premature infant may be discharged from the NICU but still have some developmental delays. The baby may have some sensory issues because everything they've smelled, tasted, touched, and felt has been impacted by being in the NICU for a long time. Maybe the baby doesn't get to experience as much in the world because they are motorically delayed. There can be some social-emotional issues because the parents didn't get to bring the baby home right after they were born. Mom and Dad are constantly worried that the baby's not getting in enough food, so the way they feed their baby is different. There can be a huge relationship between these factors.

Neurodevelopment

Neurodevelopment must be considered when thinking about the behavior. Neurodevelopment is not only how the child is developing, but it's also how the brain is developing in conjunction with overall development and how synaptic pathways are formed. Every single thing that's going on with that baby is impacting how their development occurs. In the NICU, we spend a lot of time talking to staff about the fact that it's not about who can get the most volume in an infant, it's about how that infant's neurodevelopmental occurrences are taking place. For example, every time I get a baby out of a bassinet or a baby bed and put them in my lap nicely swaddled with a bottle in their mouth, they have an experience with that feeding. There are things going on in the brain. There are synaptic pathways that are formed or deleted because of those early experiences and because of all experiences. Therefore, we really have to appreciate what feeding development and feeding disorders do in terms of neurodevelopment.

Neurodevelopment interacts with feeding, swallowing, and behavioral communication. Let's say a child is born 14-16 weeks too early and they've been trying to do things that their body would not normally have to do. They would normally be in-utero, and the mother's body would be doing everything for them. But, instead, they've come early and now has to start with experiences that are very, very atypical and very unpleasant. They have to keep their body temperature up. They have to deal with external stimuli that are way more than they should be doing at that age. They have to deal with breathing. All of those factors are going to impact their neurodevelopment.

Then, as that neurodevelopment is occurring, we start to feed them and give them things that they have to swallow. Those experiences are going to impact which synaptic pathways are going to support feeding and which synaptic pathways are going to say, "Feeding is terrible and I never want to do it again." Quickly, you start to see behavioral communication because if I'm an infant or an older child and somebody has fed me while my pathways are just being established and I couldn't breathe, or I had terrible reflux or awful motility, then the synaptic pathways are saying that was an awful feeding experience rather than a good one.

The response is, "I got fed beyond what I wanted. I got fed too much and I started to reflux." Then that behavioral communication is, "No thank you. I don't want to do this, it's terrible." It is, therefore, so important that we think about that because these children experience this over and over again. When they're saying no or when they're avoiding, it's not so that they can just say, "Oh, I want to yank my mom's chain," or "I want to yank my dad's chain." It's because neural pathways, synaptic pathways, have developed and have been strengthened that say, "Food is bad, it's dangerous. It's unsafe to me."

Another similar concept is brain architecture. There's a study of epigenetics that looks at how genes and DNA are impacted by the genetics of your parents, as well as environment and experience. It's been learned and discovered that even though your gene sequences may be the same, environment and experience impact how genes are expressed. Therefore, we have to appreciate that a child's behavior is basically communication, and it may not even be something the child is aware of.

We are born with far more neurons than we need. We start to prune the ones that we don't need and start to develop synaptic pathways to support and encourage the continuation of the functions that we are doing. If we put this in the context of children that we see in therapy, they, too, are pruning things they didn't do early on in development. Those children who are not eating by mouth, for example, are not getting any reinforcement of that neuronal function. A lot of those pathways and neurons are going to be pruned and the synaptic pathways are not going to be established. It's going to be extremely atypical for somebody who's never developed these pathways to actually consider feeding and eating as a good thing.

Feeding disorders are highly stressful, not just for the child but for the parents, caregivers, and other people involved with the child. Therefore, we need to consider the stress response in children and their parents and families.

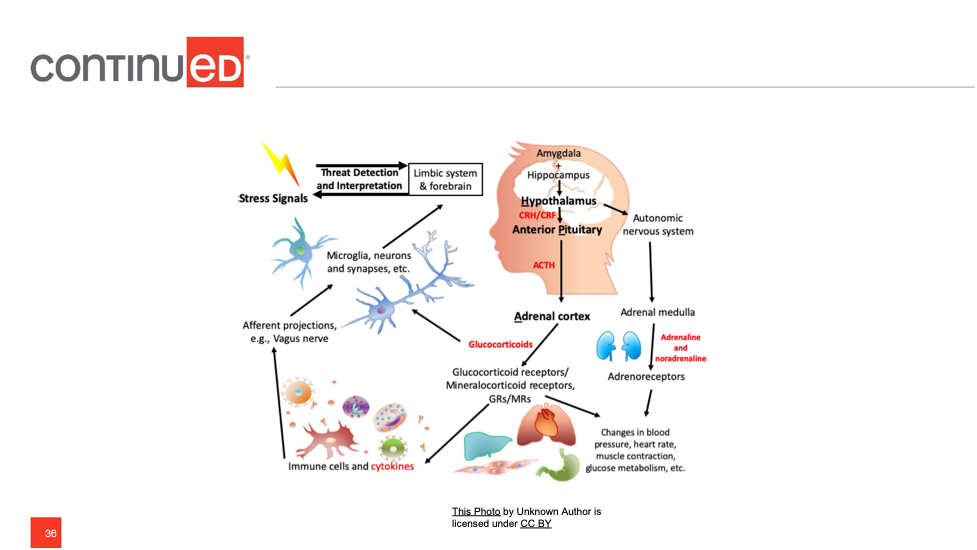

Figure 1. (See handouts for larger image.)

Looking at Figure 1, what happens? First, the amygdala picks up on some perception of danger and when that child has had all of these negative experiences with food or feeding, the amygdala is going to quickly send a signal to the hypothalamus. The hypothalamus quickly produces some hormones and sends that to the pituitary gland. The pituitary gland is going to very quickly start sending out the stress hormone, cortisol, which acts as a messenger to all of the structures of the body. This is going to happen when the child gets food items that really make them uncomfortable. If the stress is short-lived, then usually the amygdala can signal and the frontal cortex can jump in and essentially say, "Hey, prefrontal cortex, we're going to figure this out. It's all good, we can stop." However, if this is a chronic stress event, which feeding disorders typically are, then that chronic stress is going to change how things happen.

Before getting into the details of that change, let's discuss the sympathetic response that was described during that cortisol production. The sympathetic nervous system that is in action is the fight-flight-freeze system. We have increased heart rate, increased blood pressure, and increased respiratory rate. We have decreased communication, focus, and regulation. There is glucose being released, as well as adrenaline and noradrenaline being released.

Consider this example. Think about the scariest experience you could ever have. Maybe you're terrified of heights and you're on a really tall bridge. You're looking down and somebody keeps pushing closer to the edge over and over again and at that point, I come up and say, "I have a fantastic pizza. I've just picked it up, it's hot and you can smell it. Let's have a slice." At that moment, the mode you're in is, "fight, flee and freeze." You cannot even consider taking a bite of that pizza during that moment.

That is what happens when these infants or children are in this sympathetic mode. That sympathetic system is firing. We might be in a therapy session with them and some of the behaviors that you see are based on the fact that they're in this fight or flight mode. Their amygdala is overworking and the cortisol is overpumping.

The parasympathetic system helps us to rest and digest. This is where everything is normalized. We're getting optimal oxygen from the brain. Our cognition is open, we're creative and there's some self-regulation occurring. Those are all of the things that we want to see but when we have repeated chronic stress, we don't get to see that.

Chronic Stress

What is the impact of chronic stress? It can enlarge the amygdala causing it to activate more easily. The amygdala is like a watchdog. The perception of danger fires the amygdala and starts to say, "Hold on, wait a minute, this is bad." If it becomes enlarged and is activated more easily, then that is a problem for these children long term.

Chronic stress causes loss of cells and inconsistent prefrontal cortex activity. It also causes disordered storage of memories in the hippocampus that are reactivated by that stress response. Memories will be impacted, as well, by those experiences over and over again. There is also a decrease in neuroplasticity, which is when areas of the brain take over when one area is damaged. Unfortunately, some of these children have had very negative feeding experiences and have pruned a lot of the synaptic pathways and neurons that would have helped with that neuroplasticity.

What is the Language of Chronic Stress?

The language of chronic stress is the amygdala, cortisol, and that fight or flight response. It's fear, insecurity, and not feeling safe. And if I'm not safe, I'm going to show you behaviors with the intention of trying to be safe. We have to keep that in mind when we're working with children.

Parental Stress

Parental stress is definitely worthy of discussion. There are some research studies available and one group of researchers found that, when parents are chronically stressed, that can impair the mother and child's behavioral synchrony. This is referring to the sensitivity that the mother has toward the child. According to Azhari and colleagues, sensitivity toward the child's needs and ability to read their cues is impaired when parents have chronic stress (2019). They also found that there were neurophysiological mechanisms, in that not only were there behavior differences in sensitivity but there were actual changes in the functioning of the prefrontal cortex in the mothers with chronic stress which impacts their ability to problem solve and think.

The Neece group of researchers found bi-directional effects of parental stress and child behavior (2014). Basically, when children demonstrated behaviors that were not fitting social norms, the parents had higher stress. Then, the parents in turn would respond in ways that heightened the behaviors that the children were doing. For example, the child has behaviors around food and the parent has stress about that. The more stress the parent has about that, the more that behavior is seen in the child.

Landry and colleagues (2006) also found that parents with chronic stress have reduced responsiveness toward children. Additionally, the presence of insecure attachment with children when parents have a lot of chronic stress was noted in a study conducted by Tharner and colleagues (2021). One final research study, specific to feeding, found that the mother's self-efficacy (i.e., "Can I feed my child? Am I capable and competent to do that?") was decreased when the child had a feeding disorder (Aviram et al, 2014). One interesting piece of this study was that when the fathers were very involved, then a lot of their behaviors were associated with the child's behavior. For example, if the father is very involved and is working with the child during mealtime, and the child's behavior is considered to be negative, then the father's behavior mimicked that. They had a negative-type response as well.

Again, the research is suggesting that parental stress cannot be underestimated. These are the folks who are at home with the children all day, every day. Therefore, we have to consider their stress and how that's impacting the relationship with the child as well as their relationship with us as the SLP because they're the ones who we are working with and collaborating with frequently.

Therapeutic Intervention

Once we have an appreciation that children's feeding disorders have a reason and a history that's going to impact so much along the way, our therapeutic intervention is going to have to address all of those factors.

Comprehensive Goals

Let's think back to TB. Our comprehensive goals for TB are:

- TB will add 30 foods to his repertoire including 10 proteins, 10 starches, and 10 fruits and/or vegetables

- TB will enjoy a positive relationship with eating and drinking

- TB and his family will enjoy positive interaction during eating and drinking

We want this to be a relationship. We want to evoke some neuroplasticity during this process so that TB can start to have a relationship with food and be supported in a neurodevelopmental sense as well. We want to support the family in terms of their stress and their interactions with the child.

Therapy Approaches: TB

What therapy approaches did we use with TB that supported that relationship and advancement? First, we did a lot of oral motor awareness and functional training. We did food chaining and the sequential oral sensory approach (Toomey and Sundreth-Ross, 2011). We also did a lot of parent consultation and collaboration. (To be honest, TB's parents were terrific and it was fun working with them. I don't want to make myself look good and say I did all of these fabulous things. His parents were phenomenal.) Finally, we used behavioral strategies with TB because of those behaviors that we discussed earlier.

Therapy Approaches Described

For TB, first, was an introduction of non-food and food activities to introduce patterns needed for successful oral intakes. For oral motor awareness and function training, I'm not doing oral motor exercises. I was using food and non-food activities so that TB could learn about parts of his mouth and how to use them. Thinking back to what TB eats, he doesn't eat a lot of foods that require significant chewing. So, we have to consider how much is his tongue lateralized, and how often his tongue had to get into a socket and pull food out. How much has his tongue moved around? We wanted to encourage that movement.

Next is food chaining which is a feeding approach that encourages the intake of new foods that may be similar in taste, temperature, or texture to foods the child already likes and accepts. If you think about the neural pathway and how the child perceives food, it makes sense to help the child feel as safe as possible about this, and food training allows us to take foods that are already accepted and build from that so that we are not producing something that's drastically different. Food chaining allows the child to move into their interaction with food a little more safely.

The Sequential Oral Sensory Approach is another feeding approach that integrates motor, oral, behavioral, learning, medical, sensory, and nutritional factors. It is the idea that feeding is not just sitting down at the table. A four-year-old doesn't just automatically go into the kitchen, sut down and eat without having been impacted by everything that came before that. It's about smelling the food, seeing the food, and touching the food. It's 32 different steps. It's another way of saying to the child, "It's okay. This is safe." We're either reestablishing or establishing some new synaptic pathways by allowing the child to feel safe and to do things that will help them progress as we move on.

For parent/caregiver and consultation/collaboration we are working with parents and caregivers to develop goals that promote successful outcomes. I can't write a list of goals that the parent doesn't really drive and the child can't do. I don't live in their home. I don't go to the grocery for that family and make their meals. I need to write goals with the family and caregivers to make them valid.

Lastly, we have to think about behavior. We want to use that ABC model and implement strategies based on what behaviors we are seeing in the child. If I'm seeing a lot of avoidance, then I have to figure out what's the antecedent to that? Is it specific foods? Are they hot? Are they cold? We are considering all of those types of questions. Then, how are those behaviors being reinforced in the child?

Oral Motor Awareness & Functional Training. The oral motor awareness and functional training for TB included blowing, sucking, biting, chewing, licking, touching, and exploring. We wanted to promote oral awareness, new movement patterns, and familiarization with oral structures and function.

Let's go back to that proprioception we talked about earlier in terms of sensory. When I'm stressed, sometimes I grab some candy or potato chips. Why do I do that? I'm trying to organize and calm myself by biting into something. I can feel that sensation, I can taste the food, and all of those things that go along with sensory. Applying this to TB, he's had a very limited experience with those types of sensations because of the very limited intake of types of food. We want to give him some of those experiences, maybe not just directly with food, but to feel parts of his mouth that he hasn't used very much. That is why we did a lot of blowing, sucking, biting, chewing, licking, touching, and exploring.

Making Food Familiar (and Safe). Making food familiar also makes it much safer. If I have a child has developed synaptic pathways that say food is bad except for these four foods, then I am going to start selecting foods, with the help of the parents, that are similar to those preferred items because I want the child to feel safe. I want the child to have familiarity with those new items so that it's not just jumping to some new food.

I'm going to introduce those foods in a hierarchical approach. For example, if we're adding carrots into someone's diet and they can't even stand the sight of carrots, then we're going to have to start back at that sight point. We can't simply introduce foods and say, "I want you to eat this now." That's not going to work. They need to be in the room with it, see it, touch it, and follow all of the steps outlined in Dr. Toomey's SOS approach.

Additional Therapeutic Tools. As I mentioned, we're creating these goals with the family. Of course, if a family needs some feedback on a certain food that is too difficult for a child, then we have to provide our expertise in that area. But we want to have the family and the child drive the goals in relation to what foods to add in, etc.

After we implement these strategies with the families, we are collaborating with them. We are increasing familiarity by using some food training and SOS (at least that's what I did in that case). We are also appreciating the child as a whole child. Then, I can begin using behavioral strategies and other strategies to support developing a new relationship with food and achieving those goals.

- Ensure communication (AAC, Verbal, Sign, Gestures)

- Sensory strategies (Body breaks, Proprioceptive tasks)

- Provide parameters (Visual schedules, If/Then, Presentation)

- Food-related games, crafts, books (Food Bingo, Food Memory, Food Stamping, Food Jewelry, Spice Painting)

Ensuring communication – I need the child to have some way to communicate with me, whether that is AAC, verbal, sign, or gestures. Think back to the bridge analogy, if you're on the side of that bridge, you're terrified and you can't tell me that you're terrified and you can't tell me you don't want that food right at that moment, then that's not fair. We, as communication specialists, have to make sure that our clients can communicate. It also helps that person feel safer if they can communicate.

Sensory strategies - I absolutely dread going to the dentist. Every time I go, I need to use some sensory strategies. If they put the lead apron over me to take an x-ray, I don't want them to take it off. The weight of the apron is very calming for me. Body breaks are helpful in stressful situations. Let the person take a body break. Proprioceptive tasks, like carrying books around the room, can help a person feel where they are in their environment.

Providing parameters - if something is scary for you, parameters are very helpful. In terms of therapy for children, food can be very scary to them so we may want to present a visual schedule to show them what we are going to do in therapy that day. Then they can anticipate what's going to happen.

Visual schedules are also great for those who are in that "fight or flight" mode and are not able to process our oral language as well as looking at a picture. They can see when the task is going to be over and when the next task will begin.

Think about your presentation of food to the child. Let's say you've had a stomach bug, you've been sick for a few days and now I am telling you that you need to start eating again because your nutrition is gone and you're losing too much weight. So, I come in and present a huge plate of food to you. That is terrifying to you because you are thinking, "I've thrown up for the last week and now you've put this whole thing in front of me." That's really going to disrupt your feeling of security.

We can help our children out in those types of situations by providing parameters. I don't put tons of food on the plate for the child. I don't put the food out where they can see all of it. It's very much slow and gradual and in very small doses because I don't want to overwhelm them. I provide that parameter.

Food-related games, crafts, books - You can play food bingo, food memory, food stamping, food jewelry, spice painting, etc. We do these types of games and activities because we want to use neuroplasticity to develop some positive synaptic pathways so that the child can eventually eat a lot of different foods and feel safe doing it. If they don't have a lot of exposure to food or a lot of positive relationships with food, then we want to do some activities around food that can encourage a very positive relationship that may not have anything to do with eating. There are ways that they can interact with food but they're not necessarily having to eat it. They can just become familiar with it so it's not scary.

Additional therapeutic tools include using food in "other" learning activities such as counting, learning prepositions and colors, reading and verbal usage. Instead of counting blocks, have them count bites or pieces of cereal. Instead of looking at colors from a crayon box, let's look at strawberries, blueberries, bananas, apples, and all the different colors of food.

Natural food-related tasks are very important. If you have children on your caseload who have limited exposure to eating, they don't like food, or they have a feeding disorder, chances are they don't spend a lot of time in the grocery store with their parents or caregivers. There are other ways to make them familiar with foods that are not necessarily having them sit down and eat it, such as going to a farmer's market or a garden. Something where they're actually interacting with food in a way that they can tolerate.

Involve the child in goal setting if possible. Some children will be too young to do too much goal setting, however, you can involve them in some different foods. TB was able to set a few goals with us and that was very positive for him.

There should be some level of hierarchy and you can tie in activities like social events. For example, "I'm going to be able to eat this," or "I'm going to prepare this," or "I'm going to feed my baby sister something." You can have the child set up activities around the goals.

Finally, use and encourage positive language. This is very important. So many of these children have been told that they are not feeders. They've been hearing from families, "This is my eater, this is one is not my eater."

Parent consultation and collaboration. We can't underestimate parental consultation and collaboration. Parents are the experts on their children. We want to focus on the child's strength. We want to appreciate the emotional investment that the parent has and recognize their feelings about not having had this great relationship of feeding their child, which many of us have been able to enjoy.

We have to provide information to help them understand what's going on in this child's neurodevelopment. We want to respect differences in their perspectives and seek to find some common ground. We have to recognize that these parents have a lot of needs too. We have to be flexible.

Parents and caregivers are not going to function in the same way as they did on other days. Maybe they don't get a lot of sleep. Maybe they've gone to a family reunion and everybody there has told them how they can make their child eat better and now they're just in a bad place that day. We have to appreciate and recognize that when we're working with them.

Responding to Behavioral Communication for Improved Feeding & Swallowing

Earlier we discussed determining how to respond to children when they demonstrate behaviors that truly are communication. Here are some ways to respond:

- Acknowledge the communication

- Provide and encourage "functional" communication - Was TB avoiding foods by hyper-verbalizing and using a lot of extra language? In those situations, we want to provide him with structure so that he is speaking in a more functional way for us. He's not distracting from things and he's not using this extra language as a stress response. He's able to functionally communicate in that setting.

- Provide consistent parameters for that communication - If the child's communication is, "I throw things on the floor," then that's not okay. The child's communication can be, "I want to avoid this," but we want to provide the child with a way to say, "okay, I've got a spit-out bowl or I've got a specific, appropriate way to communicate that to my parents/therapist."

- Perform a task analysis for pre-feeding and feeding skills – When the child is responding or communicating through behavior, we need to make sure that they have all the pre-feeding and feeding skills they need. If they do not have those skills, we need to figure out where the breakdown is and help encourage that part.

- Provide skill-specific training which is part of neuroplasticity – If the child has real issues with chewing and they've only a munch pattern, then we're going to target that very specific skill as part of our session each week.

- Provide praise and encouragement.

- Target internal reward and motivation - We want the child to feel good about the food they're eating. We want them to feel good about their progress. We want the parents to feel the same way.

- Be consistent - If I'm working with a child and I get to the point where I've told the child, "Hey, you don't have to eat that. I just want you to poke it with the fork," and then suddenly I say, "I want to eat that," that is not ok. I have to be consistent. I have to be truthful. I have to honor what I say otherwise I'm going to make that child scared and we're going to go back through that whole sympathetic response again.

Neuroplasticity and Practice

There's been a lot of research about neuroplasticity. We want to induce plasticity in these children so that they can have a relationship with food and their parents can have a relationship with them and food. We know that neuroplasticity has to be a skill-specific practice. It has to be repeated and it has to be frequent. It has to be timely, meaning different forms of plasticity are going to occur at different stages of learning but we have to make sure when we're doing skill-specific introduction and experience, that it's at the appropriate time for the child in their development.

We also have to consider that there are other factors. How motivated is the child? How motivated is the family? Younger ages tend to be easier, there's more room for that plasticity at that point. Our environment is going to impact plasticity and our plasticity is going to impact the environment. We have to appreciate, too, that there's going to be interference. Plasticity can be good or bad but if somebody has not eaten for five years, we are not going to fix that right away. There is interference and it's going to take a while to actually get to where we want to go.

TB: Outcomes

Lastly, I want to share TB's outcomes. Initially, he had a very limited variety of intake. We wanted him to get to an acceptance of a minimum of 10 proteins, 10 starches, and 10 fruits and vegetables. He did achieve that.

"Social modifications" included TB attending social events. His mom always had to pack a lunch or pack some treats. By the end of therapy, he was attending social events without special food and liquid provided. He was eating at least some of the items at the parties and the various events successfully.

Family mealtime became much better. They were much more interactive, with minimal battles, which was wonderful for the family as well as the child. One thing his mom had mentioned early on was that they felt like they couldn't feed the child, which is so common for families with children with feeding problems. But they had low parental self-efficacy. Dad admitted frustration when he would try to get TB to eat certain things and he wouldn't do it. But both parents demonstrated a lot of great movement there. They demonstrated the use of strategies with reports of feeling able to feed their child. So, it was a very successful relationship with this family.

TB got back to those overall goals, as far as achieving the foods he wanted. Looking at other outcomes, he enjoyed and developed a positive relationship with eating and drinking. That was one of his comprehensive goals. Also, the comprehensive goal of TB and his family enjoying positive interaction around eating and drinking definitely occurred. Everybody felt much better about it.

This was a very successful case, but I don't believe it would've been if we had not appreciated all of the things that we've talked about in this course and dug in when we saw behaviors, instead of just trying to extinguish them.

Questions and Answers

In regards to the additional therapeutic tools, how do you implement the "If/Then" category while respecting the underlying cause of food aversion? I am picturing something like, "If you tolerate this carrot, then you'll get to play with blocks." That type of approach does not seem to consider the underlying cause and is purely behavioral.

I'm not going to say, "You have to eat that carrot." I don't know if you've taken Dr. Toomey's SOS, but if I have somebody who's really afraid of a carrot and it's something they really don't want, then what I'm going to say to them is, "If you can give mom this carrot…," "If you can cut this carrot in half…" We are not going to progress to, "If you eat this carrot, you get blocks." We're going to do it in very, very high levels of intricate steps of "climbing the ladder".

I do use "If/Then," but honestly, not that much. I try to build it in as part of a more natural, positive reinforcer. But I would not ever tell somebody, "If you eat this, then you get to do this." I might say, "If you hand that to Mom…, If you cut that up…" But I'm not going to push them for anything beyond that until they're ready and until they're comfortable.

Can you give an example of an extinction behavior on the part of the parent?

Let's think about TB's mom. She constantly redirects and that gives TB a chance to delay, delay, delay, delay. So, what we could do is have Mom stop redirecting and simply continue. We keep pushing ahead, continue the task, and encourage that to keep going without even saying anything.

I'm not redirecting so much as I'm actually just kind of continuing to push the tasks. For example, if we are poking an apple with a fork and Mom's saying, "Oh, come on, you have to come back. Come on, come on, come on," I'm going to reach over and poke the apple with a fork myself. I may encourage with a hand under hand to get him to do the same thing, but I'm not going to give him a delay of game.

References

A guide to working with parents of children with special needs (n.d.). https://my.vanderbilt.edu/specialeducationinduction/files/2011/09/Working-with-Parents-Guide.pdf

ASHA(n.d.). Pediatric dysphagia. https://www2.asha.org/PRPSpecificTopic.aspx?folderid=8589934965§ion

Aviram, I., Atzaba-Poria, N., Pike, A., Meiri, G., & Yerushalmi, B. (2015). Mealtime dynamics in child feeding disorder: the role of child temperament, parental sense of competence, and paternal involvement. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 40(1), 45–54.

Azhari, A., Leck, W. Q., Gabrieli, G., Bizzego, A., Rigo, P., Setoh, P., Bornstein, M. H., & Esposito, G. (2019). Parenting Stress Undermines Mother-Child Brain-to-Brain Synchrony: A Hyperscanning Study. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 11407.

Baer, D.M., Wolf, M.M., & Risley, T.R. (1968). Some current dimensions of applied behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 1,91-97.

Black, M. M., Trude, A., & Lutter, C. K. (2020). All Children Thrive: Integration of Nutrition and Early Childhood Development. Annual Review of Nutrition, 40, 375–406.

Corel, J.L. (1975). The postnatal development of the human cerebral cortex. Harvard University Press.

Delaney, A.L., & Arvedson, J.C. (2008). Development of swallowing and feeding: Prenatal through first year of life. Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 14(2), 105-117.

Dodrill, P., & Gosa, M. M. (2015). Pediatric Dysphagia: Physiology, Assessment, and Management. Annals of Nutrition & Metabolism, 66 Suppl 5, 24–31.

Filippetti, M.L. (2021), Being in tune with your body: The emergence of interoceptive processing through caregiver–infant feeding interactions. Child Development Perspectives, 15, 182-188.

Fraker, C., Fishbein, M., Cox, S., & Walbert, L. (2007). Food chaining: The proven 6-step plan to stop picky eating, solve feeding problems, and expand your child's diet. Da Capo/Life Long.

Goday, P. S., Huh, S. Y., Silverman, A., Lukens, C. T., Dodrill, P., Cohen, S. S., Delaney, A. L., Feuling, M. B., Noel, R. J., Gisel, E., Kenzer, A., Kessler, D. B., Kraus de Camargo, O., Browne, J., & Phalen, J. A. (2019). Pediatric Feeding Disorder: Consensus Definition and Conceptual Framework. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, 68(1), 124–129.

Goday, P. S., Huh, S. Y., Silverman, A., Lukens, C. T., Dodrill, P., Cohen, S. S., Delaney, A. L., Feuling, M. B., Noel, R. J., Gisel, E., Kenzer, A., Kessler, D. B., Kraus de Camargo, O., Browne, J., & Phalen, J. A. (2019). Pediatric Feeding Disorder: Consensus Definition and Conceptual Framework. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, 68(1), 124–129.

Jones, B. (Ed.). (2003). Normal and abnormal swallowing: imaging in diagnosis and therapy. (2nd ed.) Springer-Verlag.

Kleim, J. A., & Jones, T. A. (2008). Principles of experience-dependent neural plasticity: implications for rehabilitation after brain damage. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research: JSLHR, 51(1), S225–S239.

Landry, S. H., Smith, K. E., & Swank, P. R. (2006). Responsive parenting: Establishing early foundations for social, communication, and independent problem-solving skills. Developmental Psychology, 42(4), 627–642.

Morag, I., Hendel, Y., Karol, D., Geva, R., & Tzipi, S. (2019). Transition From Nasogastric Tube to Oral Feeding: The Role of Parental Guided Responsive Feeding. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 7, 190.

Morgan, C., Novak, I., Dale, R. C., Guzzetta, A., & Badawi, N. (2016). Single blind randomised controlled trial of GAME (Goals - Activity - Motor Enrichment) in infants at high risk of cerebral palsy. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 55, 256–267.

National Scientific Council on the Developing Child (2010). Early experiences can alter gene expression and affect long-term development (Working Paper No. 10).

Neece, C. L., Green, S. A., & Baker, B. L. (2012). Parenting stress and child behavior problems: a transactional relationship across time. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 117(1), 48–66.

Pérez-Escamilla, R., Jimenez, E. Y., & Dewey, K. G. (2021). Responsive feeding recommendations: Harmonizing integration into D\dietary guidelines for infants and young children. Current Developments in Nutrition, 5(6), nzab076.

Pérez-Escamilla R, Segura-Pérez S, Lott M. (2017). Feeding guidelines for infants and young toddlers: a responsive parenting approach. Nutrition Today, 52(5):223–31.

Shinglot, K.N., ( 2019). Human behaviour-normal and abnormal [PowerPoint slides]. Slideshare. Retrieved from: https://www.slideshare.net/DrKiranShinglot/human-behaviourppt

Stangor, C., & Walinga, J. (2014). Introduction to psychology: 1st Canadian edition. BCcampus. Retrieved from https://opentextbc.ca/introductionto

Sulzer-Azaroff, B., & Mayer, G. R. (1991). Behavior analysis for lasting change. Holt, Rinehart & Winston

Tharner, A., Luijk, M. P. C. M., van IJzendoorn, M. H., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Jaddoe, V. W. V., Hofman, A.…Tiemeier, H. (2012). Infant attachment, parenting stress, and child emotional and behavioral problems at age 3 years. Parenting: Science and Practice, 12, 261–281.

Toomey, K.A., & Sundess-Ross. E. (2011). SOS approach to feeding. Perspective in Swallowing and Swallowing Disorders (Dysphagia), 20(3), 82-87.

Ward, K. P., & Lee, S. J. (2020). Mothers' and Fathers' Parenting Stress, Responsiveness, and Child Wellbeing Among Low-Income Families. Children and Youth Services Review, 116, 105218.

Citation

Mattingly, R. (2022). Management of Behaviors During Feeding and Swallowing Intervention. SpeechPathology.com. Article 20521. Available at www.speechpathology.com