Introduction

Before getting started, I do have some disclosures to share. I am the owner of SMARTER Steps which is a consulting business for special educators, therapists, administrators & parents. I receive royalty payments or honorariums as a presenter. I am the co-author for a book named SMARTER Steps Guide to Creating Smarter IEP Goals. I do not have any relevant non-financial disclosures to share.

In addition to serving as an SLP in multiple settings, I've served in a variety of roles in the school, in administration and as a regular education teacher. I have served almost every position around the IEP table which leads me to this topic that I'm so passionate about. I am going to discuss student-driven IEPs which is also referred to as “student-led IEPs” in the literature. What I plan to focus on specifically is increasing participation at all levels.

The concept of student-driven IEPs has been growing. In the last decade, there's been a lot of increased discussion amongst educators about including students and increasing their participation in the process. But, to date, there haven’t been very good ways to help students become involved. There hasn't been a lot of sensible routine practice at it in this regard. There are a lot of benefits and, fortunately, the benefits outweigh the barriers. It just hasn't become routine practice yet.

There are over eight million students who have IEP services annually. Many of those students do not have a well-designed transition plan into the community. A lot of students continue to struggle with many aspects of independent living including jobs and long-term relationships after graduation. How do we change that? How do we help our students in the long run?

Student-Driven IEPs

Dr. Paul Wehman explains transition in this way, “Transition is an outcome-oriented process that is individually driven by the student's vision of adult life. Post-school goals should drive the transition planning process…” The annual IEP should be the tool that outlines the specific steps to get the student there. As educators, we tend to focus primarily on academic skills related to district or state standards. While that's important, preparing students to participate in the IEP meetings can offer other opportunities and help them learn and practice critical life skills. To me, life is about being able to handle yourself with strength and dignity in the toughest of situations. Those of us with advanced clinical degrees know that life is about doing that.

Self-Determination

Michael Wehmeyer points out that self-determination is a combination of skills (2003). Skills, knowledge, and beliefs allow a person to engage in goal-directed, self-regulated, autonomous behavior. That, obviously, looks different for everyone. We have different goals, different interests, and different desires. We all make choices and have different problems. All of these factors together contribute to the function of a person's actions or behaviors that can help, or in some cases, hinder us from becoming a primary causal agent in our own life. All of these variables indicate that teaching self-determination must be specifically designed to meet the individual student's needs. It's not a cookie-cutter approach. We have to have an understanding of the student's strengths and limitations and really get to know them. We need to understand what students believe and what goals they want to set in order to effectively help them increase their self-determination skills.

There is an analogy that describes self-determination in this way. If students floated in life jackets for 12 years, would they be expected to automatically know how to swim if those jackets were suddenly taken away? Probably not. This situation is similar for students in special education. In many cases, they're not taught how to self-manage or self-direct their own lives before graduation. That can cause some real problems for our students. Some reflection questions that I use to help guide me through this process with students: How do my students learn responsibility? How do they learn to be independent thinkers, critical thinkers or problem solvers? How can I teach them to identify their own needs and advocate for themselves? Student-driven IEPs correlate with more positive post-secondary outcomes such as employment, independent living and even community inclusion.

Current Research

Wehmeyer and colleagues conducted a five-year longitudinal study in 2013 to find a causal relationship between providing self-determination instruction and improved student outcomes in the long term. The purpose of the study was to examine the effects of various interventions that promote self-determination. They used a randomized trial placebo control group and studied 50 different schools across the Midwest. 493 students with diverse disability diagnoses and their teachers across different campuses were included in the study. The results of this study support Dr. Wehman's earlier explanation of transition. They found a logical connection between self-determination and student-driven IEP meetings and reminded us that the IEP is the most important document developed regarding the student's abilities in their educational program and life skills after school.

Critical issues are discussed and important decisions are made at the IEP meeting. The researchers point out that if the IEP is developed without the student or with only token involvement, then the student learns that his or her voice doesn't matter. They also learn that important decisions are best made for them. This, of course, can compromise and even sabotage any subsequent self-determination lessons down the road.

The study suggests that interventions to promote self-determination can result in significant changes for students. Students who participated in self-determination interventions over a three-year period showed significantly more positive patterns of growth than students who were not exposed to lessons during the same time period. This is significant because it's the first study to really examine the causal impact of direct interventions on student self-determination. It also supports previous studies indicating that if students with disabilities are provided explicit instruction and opportunities to participate in their educational planning, then they can enhance their self-determination and critical life skills. Since promoting self-determination skills have been linked to a more positive adult and post-secondary outcomes, teaching these skills should become best practices.

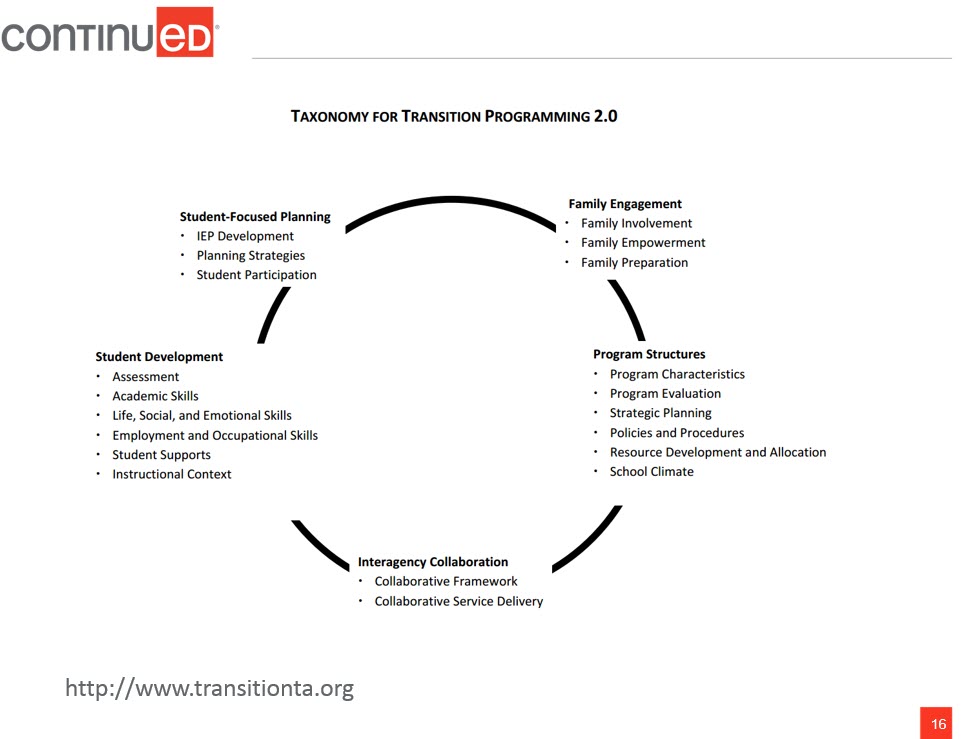

In 2016, Paula Koehler developed the framework in Figure 1. It was designed to organize effective practices related to post-school outcomes. She further breaks down this framework to include evidence-based practices and the skills that they target. Student involvement is highlighted in both the planning and development of their futures.

Figure 1. Koehler’s model for transition programming.

This model shows that intervention focuses on increasing student awareness of things that we take for granted such as basic life skills, awareness of individual strengths, and functional limitations. This framework was designed to help students increase self-determination and self-advocacy skills.

Historical View of Disability

It's important to review the historical views of disability in the school setting. Of course, in the past, disabilities were rarely viewed as an interiorized state similar to health problems such as an individual pathology (i.e., a problem that resides within the person). Within that context though, disability is understood as a characteristic of that person and they're often seen as pathological or broken. Over time, this perception has developed into negative stereotypes of people with disabilities. I think that's particularly true with cognitive disabilities. One major example was with the introduction of mental age estimates which I believe led to “infantilization” of people with disabilities.

Although I plan to cover a lot of information in this course, one idea that I want to highlight is that as a society we tend to underestimate the abilities of students with disabilities. Because of this, we often require less of them which in turn prevents the development of many essential life skills. Sometimes, we unintentionally thwart a student's self-confidence or self-esteem and inadvertently their independent living skills.

Traditional Programs

Before discussing a program that promotes self-determination and self-advocacy skills, we need to understand the nature of previous programs. The traditional programs tended to underestimate student's abilities and focus more on controlling their surroundings. They were designed to meet that perceived diminished capacity and other negative stereotypes that had developed over years. In doing so, a student's opportunities for growth were really limited. Today, we know that children need opportunities to practice skills and experience successes as well as failures. Students need to learn to be reflective and show some analytical skills so they can improve. If we're controlling those opportunities, we're controlling their outcomes. So, it's really important to remember that. Children with limited experiences will become adults with limited skills. Furthermore, the research suggests that these adults are at risk of having long-term difficulties in the workplace, managing their finances, having unhealthy relationships and may even become socially isolated.

The idea with student-driven IEPs is to offer a contrast to traditional programs. By increasing a student's participation in their own IEP development, we can help them discover their abilities and push them forward to reach their maximum potential. The focus shifts from deficit-based to strength-based. In addition to the long-term benefits, there are two essential benefits of increasing participation in the here and now. First, student participation can create a collaborative climate which is something we all strive for in IEP meetings. And second, it really focuses on increasing student skills.

When we talk about creating positive collaborative climates, we need to keep in mind that the primary educational goals for students include success and happiness in life, the “big picture” stuff. Student input in their own education can increase buy-in. It can increase effort and overall self-determination skills. The second major benefit is that student-driven IEPs are fostering skill development. We're essentially acknowledging that students will be adults and that they need these skills for successful, independent living.

Student Involvement in Education

By implementing more student involvement in the IEP process, we can help them have more input. With more input, students begin to take an active role. We want to shift them from that passive role where we're dictating the IEP meeting and increase their participation into a more active role. Student-driven IEPs tend to focus more on strengths and accomplishments rather than the child's disabilities. When an IEP meeting focuses on growth and effort, of course, that atmosphere tends to be more positive. Therefore, it makes sense that true collaboration is achieved easier without team members being on the defensive. Students also learn about the IEP process and documentation when they become involved which can have tremendous benefits, especially with helping them gain greater insight about the time and effort that we put into their IEP development. That's something that I think is really lacking. It's a great thing to help students gain perspective from the educator's role. It facilitates empathy and understanding. It heightens the awareness of our time, our responsibilities and the challenges that we can face while developing their IEPs.

Benefits for Parents

Parents also find that student-driven IEPs provide benefits. In my experience, their participation will also likely increase. Parents can see firsthand the student's growth while participating. This positive atmosphere allows for increased IEP development over the traditional IEP meeting where teachers show up with their already-prepared document and read the parts to the family. That is something that we do for our comfort but it doesn't necessarily make the parents or the students feel comfortable. Obviously, we have to get through all the pieces of the IEP and we have to cover everything that's mandated. Hopefully, as we continue, you will see which approach has more collaboration and a better feel to it.

I would like to share an example of a young woman, Michelle, who has Down Syndrome. When she was in school, her IEP team made all the decisions for her. She really had no say early on even into high school. In fact, Michelle really wanted to take a typing class but her teachers told her no. They believed that because her fingers were too small, she wouldn't be able to type. However, Figure 2 shows her working on a very detailed craft project. Given that task, do you see her as having limited finger movement? The teachers worried that she wouldn't be able to keep up in class and succeed simply based on the curriculum standards.

Figure 2. Student example.

IDEA Transition Definition (20 USC 140 (34))

Let's review the IDEA Transition definition and what the law mandates. It states that activities for a disabled student should be designed with an outcome-oriented process which promotes movement from school to post-school activities. That has to be a focus in transition. The second point is that it must be based on the student's needs. That means you must consider student preferences and interests. Lastly, it must include instruction-related services, community experiences, and all of those post-school living objectives when appropriate to help them acquire daily living skills and functional vocational evaluation.

Michelle ended up advocating for herself in our IEP meeting as she challenged the team to change their mindset. Instead of making her conform to the core standards as they were written, she encouraged the team to make accommodations and modifications to help her succeed. She requested that they provide her with adaptive equipment and provide similar but modified instruction. The really fantastic thing is that Michelle went on to type 45 words per minute and used the skill in her first job after graduation.

Research shows that the education of students with disabilities can be made more effective by ensuring their access to the general education curriculum. We can specifically design instruction to help students meet and access the general curriculum. So, with regard to Michelle's case, I didn't feel like Michelle's teachers told her the right things. They told her that she couldn't take a typing class because her fingers were too small. They didn't believe she could successfully learn how to type. It seemed that their reasons really aligned with those traditional views of her disability. Ultimately, they were limiting her personal growth. She didn't meet the school's expectations to successfully participate in their curriculum as they had it designed. Yet, they weren't willing to modify the curriculum. Their solution was to just tell her no. Looking back at that federal definition, it appears that they didn’t follow those regulations.

The important thing for Michelle is that the soft skills she gained while advocating for herself in school, has helped her in life. She started her own business. She's currently the owner of Company MEA which is a local photo scanning and personalized crafting service. With support, she's gained higher-level job skills, such as acquiring grant funds, marketing to local entrepreneur groups, advertising in social media and even running her own business. She continues to seek guidance and support from others around her and wants to increase her knowledge and skills. She's really driven to improve.

What does all of this mean for students while they are in school? How important is student participation in the IEP process? These are questions that we should start asking ourselves. There is a district in Georgia that summed it up in this way: student-driven IEPs are a matter of practicality. Students are required members of the IEP team at the transition age. They've found that students weren't able to be productive members of transition conversations or planning when prior inclusion opportunities weren't provided to those students. The district also pointed out that at age 18, rights are transferred to students. Parents can only access student records with student permission or a court order. As you can imagine, many of the students were signing themselves out of special education or dropping out of school. They reported that many of the students with disabilities simply were not graduating.