Editor's Note: This text is a transcript of the course, Incorporating Animal-Assisted Therapy into Speech-Language Pathology Clinical Practice: An Overview, presented by Sharon Antonucci, PhD, CCC-SLP.

Learning Outcomes

As a result of this course, participants will be able to:

- List skills and aptitude required for animal-handler teams.

- Describe benefits and challenges of SLPs also acting as animal handlers.

- Describe goal-writing for clients with whom animal-assisted therapy is incorporated into treatment.

Introduction

This topic is close to my heart, so I want to thank everyone for taking this course.

Animal-Assisted Activities (AAA)

The first topic I want to review is animal-assisted activities. For this, the animal-handler team will go to a location and make themselves available to a variety of people for spontaneous interactions. The handler does not come in with any individualized expectations or plans. Examples of these activities include visits to nursing homes or hospitals, public libraries, and college campuses.

Animal-Assisted Therapy (AAT)

Animal-assisted therapy is a clinician-provided service within that clinician's scope of practice. Everything that goes into a session requires a licensed clinician. Client progress toward individual goals is documented. Also, session plans and timing is dictated by clinical practice. Whatever is appropriate for that individual is delivered by that clinician, including the participation of an animal handler team.

Animal-assisted therapy is similar to any other technique that a clinician might use. Animals can serve as communication partners and communication facilitators. Remember that they are not manipulables or materials. Animal-assisted therapy is not a meet-and-greet or playtime with the animal.

It is also not about the animal being the clinician. The licensed human clinician is still providing treatment and the animal is a partner in that. Also, it is not therapy for the animal. We do not incorporate animals who do not want to be there. If an animal has not demonstrated enthusiasm for interaction or a tolerance for the rigors of therapy, we will not include them.

Service Animal

Service animals are another kind of distinct category of job for an animal. This is when an animal is trained to perform specific tasks for one individual with a documented disability. While they are not pets, they deserve the same love and care that any other animal living in someone's home deserves.

An important distinction is that service animals are the only animals who are protected by law regarding public access. Therapy animals are not as protected. Per the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), the only animals that can be considered service animals are dogs with some separate provisions for working with miniature horses.

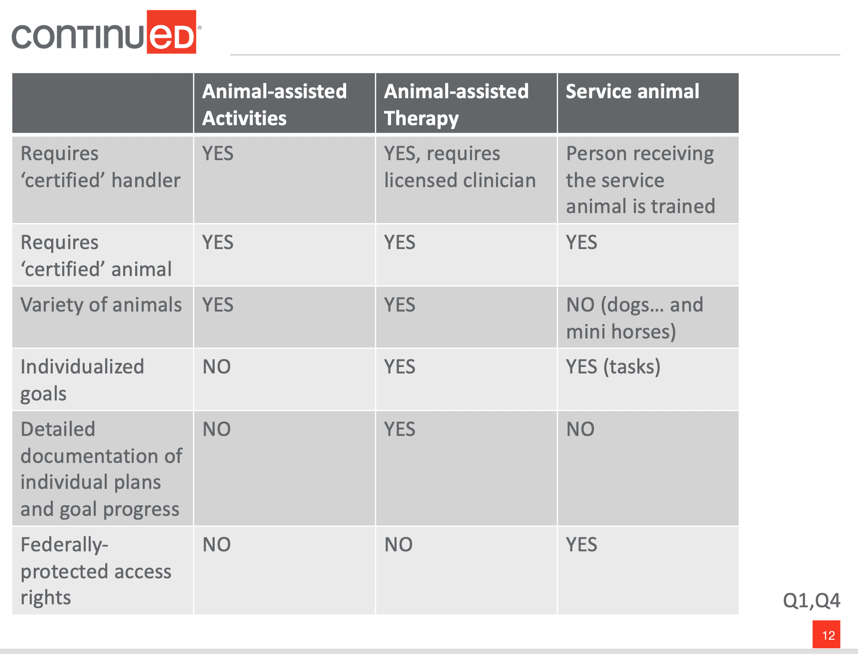

Figure 1 is a summary that indicates some differences related to handler status, status of the animal in terms of being certified, and so on. It also summarizes the differences between AAA, AAT and service animals:

Figure 1. Summary of AAA, AAT, and service animals.

AAT Evidence Related to General Health & Wellbeing: Nonhuman Animal

I also want to summarize the evidence related to the incorporation of nonhuman animals into treatment. One quote I want to mention says, “To know for certain that X is not exploiting Y, merely using Y, X must repeatedly make choices that substantively further Y’s welfare even when in conflict with X’s own prudential motives.” It is important to keep in mind the consideration of partnership versus exploitation when it comes to the animal. This highlights the dual responsibility that clinicians have, especially when clinicians are also acting as the animal handler in the context of animal-assisted therapy.

In terms of the animals who participate in therapy, it is important to ask ourselves if the animal benefits from the relationship. The evidence of domesticated animals’ benefit is different for more wild or exotic animals. When looking at the literature, most of the work is done with dogs. There is less information known about the potential benefits to other animals.

There is also variability relative to whether the animal participated in animal-assisted activities or animal assisted-therapy. People have looked at physiological measures of the animal's stress and comfort level, as well as behavioral measures. An important aspect is the familiarity with the location of the activity or therapy, as well as familiarity with the handler. You also want to consider the factors related to the logistics of the sessions. How long are the sessions? How frequently are the sessions occurring? How many breaks does the animal get during a session?

Therapy Animal Sessions: Becoming a certified therapy animal-handler team

It is important to consider certain factors when deciding whether to become a certified animal handler. There are a number of programs that can do the training and assessment to provide that certification. Many of them focus on dogs. Pet Partners certifies a wider variety of animals, including cats, rabbits, and domesticated farm animals. We can also have clinicians working with the animals rather than be the visiting animal handler team. They can work with a facility or resident animal. One organization that certifies facility animals is Canine Companions for Independence.

Rules of Thumb: Accepted Stories

Much of my information is informed by my experience with Pet Partners. I have done handler training with them and observed many animal handler evaluations. They are the organization with which I am most familiar, but there are commonalities across programs.

In terms of species that are accepted into animal handler training, this would include domesticated animals that have recognizable and documented cues. This way we can interpret when the animal is trying to communicate with us, whether it is interest, stress, or fatigue. There should also be evidence of a demonstrable interest in being with humans. Some of these animals include dogs, cats, horses, guinea pigs, and rabbits.

Ineligible or Inappropriate Species

Still Developing

Ineligible or inappropriate species include animals that are still developing. This refers to animals who have not yet reached their maturity. These animals are still forming their personalities and preferences. Also, they may still need their shots in order to keep themselves and others safe.

Wild & “Exotic”

Other animals that are considered ineligible are wild or exotic animals. There is not a lot of sufficient information to reliably judge the animals’ communications. Certain animals are meant to live in the wild, which means they would have to be held in captivity to be participating in these activities.

Dolphin-Assisted Therapy

Additionally, some work has been done in the area of wild animals around dolphin-assisted therapy and the potential problems in that kind of work.

Our Focus

The focus for this course is going to be clinicians working with certified therapy animals, as well as the special considerations for animal-assisted therapy. When thinking of a good candidate for animal-assisted therapy, the animal would need to demonstrate specific skills and preferences. Handlers also need to have knowledge and skills related to maintaining animal welfare and being clear about the different types of animal partners that are appropriate. There are benefits and challenges of the clinician acting as the animal handler. These factors relate to client candidacy, health and safety precautions, and liability related to using animal-assisted therapy as one of your techniques.

Therapy Animals

Therapy animals are commonly dogs, but unlike service animal designation, they do not have to be. Therapy animals must be domesticated for most certification programs. In terms of general qualities, there are health- and diet-related parameters that need to be maintained. For example, some programs will not certify animals that are fed a raw diet because of concern for possible transmission of sickness. The animal has to be in good health and be well-maintained in terms of hygiene and grooming. The animal needs to be what is considered reliable, controllable and predictable.

The animal should actively solicit interactions from people, not just quietly tolerate them. Therapy animals need to be accepting and forgiving of differences in people's reactions and behaviors. Participants may have differences in vocal quality or ways of movement differences, and the animal needs to be comfortable with all of those differences. Therapy animals should like to be petted and should remain calm in a variety of distracting situations.

Skills Required

Non-Human Animal

In terms of the skills that are required for the animal, here are some questions to consider:

- How does the animal manage activities of daily living?

- How well does the animal tolerate grooming?

- What is the animal’s overall health?

- How does the animal react in standard situations?

- How does the animal respond to strangers coming up to them?

- How does the animal respond to another animal being in the area?

- How responsive is the animal?

- How predictable is the animal’s behavior relative to basic obedience?

- Will the animal come when called?

- If they are an animal that would be carried, what are their basket skills?

Also, consider what the animal has to demonstrate regarding people skills:

- How does the animal feel about inappropriate petting?

- How does the animal handle interacting with large crowds of people?

- How does the animal deal with loud sounds, such as people yelling?

These are all a part of the skills and aptitudes that an animal needs to demonstrate in order to be certified as an animal that can participate in animal-assisted activities or therapy.

Animal Signals: Therapy Animals and Stress

One of the most important skills of a handler is to be able to recognize animal signals. This is when animals try to communicate with us. An example of this is displacement behaviors, which is when animals communicate that there is something bothering them by trying to suppress their reaction to it.

Signs of Distress

Here are some other signs of distress. A lot of these examples are appropriate for dogs because they tend to be the more common type of animal used in animal-assisted therapy:

- “Whale eye”

- Tongue flick

- Panting

- Hypervigilance

- Tucked tail

- Tense body, tense “hackles up”

- Backing away or cowering

- Growling/barking/snapping

- Differences in physical features may make it more or less difficult to “read” these signals

This topic brings up the discussion of particular breeds of animals. For example, it is not the case that Staffordshire Terriers or German Shepherds are ineligible. It is not about the breed, it is more about the animal's behavior.

Calming Signals

These are some other examples of the kinds of communication that animals may give us:

- Sniffing the ground

- Blinking, averting the eyes, turning away

- Yawning

Other Animals

If you are interested in working with a different kind of animal, you need to make sure that you are knowledgeable about and comfortable recognizing and responding to the cues that they might give you.

Handler

There are certain qualities that a handler needs to have. To be an appropriate handler, you need to demonstrate a pleasant, calm, and friendly attitude toward the animal at all times. This should occur regardless of how stressed you are or if the animal is doing what you asked.

Handlers also need to demonstrate that they are able to remain calm, irrespective of the circumstance. You have to be able to effectively read your animal's cues and act accordingly, whether it is taking them out of a situation or supporting them during an interaction. This can be done by having a light hand on them or just staying close.

Handlers should also want to protect and respect the animal’s needs while maintaining appropriate interaction with clients. It becomes a dual responsibility because you have two top priorities: the client and the animal. The main theme that is a part of the training curriculum is that the handler should always be acting as the animal’s advocate in all situations.

Handler Response and Responsibilities Around Animal Cues

It is the handler’s responsibility to be monitoring all cues and looking at how frequently the animal is distressed. For example, how long of a session can the animal tolerate before they start to demonstrate real fatigue? Is the animal demonstrating physical discomfort, such as limping or wincing?

It is important to remember that being an animal's advocate can mean knowing that they would want no part of being on an animal handler team and keeping her away from it, no matter how much we might want to do it with them.

Certification

Another important factor to keep in mind about certification is the result of the evaluation of an animal handler team. For example, if you are a certified handler, you can only work with the animal with whom you got certified. This is because the animal is always being assessed in relation to the skills and aptitude of the handler. It is about looking at the relationship between the animal and the handler. How well does the handler respond to the animal? How well is the handler able to attend to both the animal and whatever else is going on around them?

Clinicians as Certified Handlers

This brings up the question: should clinicians be handlers? I think that they can and should be certified handlers.

- Benefits

- More direct access and integration of animal into therapy

- Avoid training another person in SLP procedures

- Avoid potential complications associated with confidentiality

- Challenges

- Balance needs of client and needs of animal (ASHA CoE and animal welfare)

- Must be another person available in case of ER (client or animal) or planned break

There are benefits to being a clinician who is also an animal handler. This includes more direct access and integration of the animal into therapy. You do not have to spend time training another person for what is going to happen in the treatment, what kinds of clients they will be working with, ethics, confidentiality and so on.

However, there are also challenges that we need to be aware of as a clinician and a handler. You need to balance the needs of your client as well as the needs of the animal. For example, if you are in a private practice situation, you need to make sure that there is someone else in the vicinity who is available in case of an emergency. The client nor the animal can be left alone.

Clinicians Working with Other Certified-Handlers

There are benefits and challenges to a clinician working with someone else.

- Benefits

- Focus attention more exclusively on client

- May be easier to balance in cases in which you only have 1 or 2 client candidates

- Challenges

- Train non-clinician handler in procedures associated with SLP treatment

- Must train and supervise related to client confidentiality, facility requirements & restrictions

- More difficulty associated with logistics and scheduling

- Less familiarity &/or training time with the therapy animal

Another certified handler allows the opportunity for the clinician to focus more exclusively on the client. It may be easier to balance in cases where most of your clients are not animal-assisted therapy participants.

There are also challenges with incorporating someone who is not a clinician in your therapy. It means that you, as the clinician, will have less familiarity and training time with the therapy animal. It is also a possibility that a speech-language pathologist may be co-treating with another clinician, who is the certified handler. In that case, some of these challenges are not as relevant. In the hospital where I work, one of the recreation therapists is also the certified handler. We have a facility dog who lives with the therapist and comes in with her to work.

Client Candidacy for AAT

Whether you elect to be the certified handler or not, there is a lot that needs to go into thinking about client candidacy for animal-assisted therapy. This means looking at whether any inherent risks of involving a non-human animal in your practice are outweighed by the potential benefits.

For some clients, animal-assisted therapy is simply not an option. Here are some potential contradictions:

- Contraindications and precautions

- Risk : Benefit

- Contraindications = NO AAT

- Client or guardian declines participation

- Physician declines participation

- Open wound that cannot be safely covered

- Overt signs/symptoms of aggressive/violent behavior

- Policy, procedure guidelines would be violated

- Managing an environment in which there is a mix of appropriate and contraindicated clients

- Allergies

- Client contact and its alternatives

- Policies and documentation

One of the primary components of client candidacy is that there should not be any animal-assisted therapy in cases where there is a danger of harm, either to the client or the animal.

Another point related to client candidacy is that you may be in a situation where you need to manage an environment with a mix of appropriate and contraindicated clients. What alternatives can you pursue with respect to keeping the population separate as needed? We also want to consider alternative animal-assisted therapy activities for someone who is interested but may have a health contraindication.

Client Procedures

In terms of some procedures, a number of permissions are typically appropriate to acquire before engaging in animal-assisted therapy such as the client's permission, if they have a guardian, their physician, as well as other clinicians who are also working in your environment who might be impacted by the presence of the animal. It's often appropriate to get a history from the client about their own history with animals, whether they've had companion animals in the past or any other history they might have with animals. Determine what their health history is and what their infectious disease risk is relative to the possibility of being in the presence of zoonotic diseases, which are diseases that can be transmitted across species. Is the person is immunocompromised, for example?

Again, are there any behavior contraindications as I mentioned earlier? Do they demonstrate aggression or violent outbursts? Typically AAT is not suggested for a client who has hallucinations or delusions.

Finally, animal fears or phobias are important to keep in mind. Animal-assisted therapy is not aversion therapy. It's not the job of the animal-assisted therapy team to help someone get over their fear of an animal. So that wouldn't be an appropriate client.

AAT in Speech-Language Pathology Clinical Practice

In terms of clinical practice factors, how do I change my goals in the context of AAT? The answer is you do not. Your goals are your goals for whatever the needs of the client are, whether they are centered around motor or speech, voice, language, and so on. It is about the method that you are using to target those goals that you are incorporating.

In terms of how we measure effects, speech and language gains are documented as they typically would be. This could be about a standardized assessment battery, particular responses to certain target items, and so on. We also want to measure the effects of the animal's participation and look for gains that may be solely resulting from participation with the animal. This may require not only item-specific measurement, but language sampling, looking at conversation-based goals, or pragmatic goals. You will also want to look at client satisfaction with the treatment, as well as quality of life ratings.

Here are a few examples of the behaviors we may be targeting in treatment and what that potential AAT method might look like (Click HERE).

For example, a client with aphasia may have a goal related to increasing the length and meaningfulness of utterance or increasing the number or type of words in the lexicon. AAT methods could include providing cues of increasing length to the animal or being asked to name concepts associated with the animal.

Outcome measurements would be any standard clinical measures that you may use, such as language sampling, mean length of utterance type-token ratio, and so on. Another example is increasing topic initiation and topic maintenance with either a familiar or unfamiliar partner.

A team method could be having the client introduce the animal to a certain number of new people using a certain number of words. You may have them tell pieces of information about the animal to another person, or respond to questions about the animal from another person. Again, the opportunities you have for outcome measurement are the same that they would be in any other clinical context.

Additionally, I included other examples that you can use as thought experiments. I recommend engaging in these if you are interested in other ways you could incorporate an animal-assisted therapy method to target speech-language behavior. It is important to be aware of how you could alter these protocols for someone who is motivated but cannot have contact with animals. Virtual opportunities might be an example of incorporating AAT. You can do a video call with an animal handler team and have the person write materials for a plan.

AAT Planning Process

In terms of planning, animal-assisted therapy is traditional therapy. You have access to all of the tools and strategies of traditional therapy, but now you are supplementing those with the capabilities and preferences of the animal that you are working with.

The typical cornerstones of good clinical practice are critical in the context of animal-assisted therapy. This includes all of the things that we would be doing before, during, and after sessions. Examples of this could be communicating with clients, communicating with guardians, and preparing plans with people that we co-treat with. You still want to think about health and safety and hand-washing procedures because they are important in the context of animal-assisted therapy.

Also, you still want to reflect on how the session went. What worked and what did not? How was the animal responding? Are there things that need to be tweaked to increase the benefit? Document these aspects before, during, and after sessions, and then communicate any revisions to the rest of the team.

Environment Assessment

In terms of environmental assessment, think about where you might be doing animal-assisted therapy. You want to think about who on the staff is available and willing to be involved. Consider the clinician and handler responsibilities, as well as any support personnel that might be available to help in emergencies.

This gets us into client interactions. This includes the clients being served in the AAT program and those who are not, but are still coming into the environment. What is the environmental activity level? Is it a busy hospital? Is it a quiet private practice? Is it a grammar school versus a high school? How does that inform your thoughts about where the sessions will take place? How long will the animal be involved in the session? Keep in mind for both the client and animal what environmental distractions might be present.

You also want to do your best to remember that animals have different sensitivities than we do. They see, hear, and smell from a different perspective. Smells that we might not even notice might be off-putting or distracting to an animal. They also perceive motion differently. Be aware of movement in the background because it might not be distracting for us, but it may be for the animal. Think about the environment from the animal’s perspective, as well as yours and the clients.

Health and Safety

In terms of health and safety, infection and safety control policies and procedures need to be respected. It is important to have conversations with your infection control staff about the possibility of incorporating an animal into your treatment. You need to know who needs to be contacted and informed about the presence of the animal.

If you are the handler, what is going to be happening with the schedule and what kind of animal is going to be present? Make sure that all the documentation around the animal is up to date. This includes vaccinations, inoculations, and so on.

Any staff members or other contacts that need to be involved include infection control staff, if your facility has such staff. If you are the first person who is going to be doing AAT wherever you practice, it is often appropriate or required that you have a facility policy agreement in place. This way, the parameters of what is going to happen and what is allowed to happen are agreed upon by everyone involved before the program is initiated.

AAT Documentation: Some Considerations

In terms of documentation, it is important to keep in mind that AAT is not a separate field of practice. It is a method that clinicians incorporate within activities appropriate to their clinical scope of practice. Animal-assisted therapy is neither the goal nor the behavior. It is instead an activity that is incorporated to help the client progress toward their goals.

In your documentation, you will record the goals and behaviors being addressed. You will also document whatever activities were implemented to help move the client toward that goal, including whatever the animal-assisted treatment activities were.

Liability: Some Considerations

Here are some points relative to liability:

- If you are a clinician-handler

- Professional liability insurance

- Volunteer insurance provided by certifying agency

- Documentation of permissions and health/safety checks

- If you are working with another handler

- Professional liability insurance

- Documentation of client/guardian/physician permissions

It may be the responsibility of the handler to maintain his/her own volunteer insurance and maintain health/safety related to animal, but it is also your responsibility to confirm and document.

Depending on whether you are covered by your employer, you may need professional liability insurance. Some of the organizations that certify animal handler teams might provide volunteer insurance.

Even if you are not the handler, it is still the clinician’s responsibility to document any permissions that are required and to make sure that they have records related to the health and safety of the animal and the handler.

Summary

In this discussion of animal-assisted therapy in the context of speech-language pathology, I have included a handout of references.

Questions and Answers

Are there any studies showing the efficacy of virtual animal-assisted therapy versus in-person?

I am aware of a few studies that have looked at whether the live animal is integral to animal-assisted therapy. Some incorporated virtual animals in the context of animal-related television as opposed to, for example, a Zoom meeting with an animal. However, there is not a ton of information on this and this is an area of inquiry that is ripe for additional studies. Hopefully, some of you will be contributing to that evidence base.

Can the cost of purchasing an animal specifically for animal-assisted therapy be written off as a business expense?

I have never heard anyone talk about it. Most of the people I have interacted with who do animal-assisted therapy already had an animal that they felt was appropriate. They then proceeded with the training and certification. The recreational therapist at our facility applied to be eligible with Canine Companions for Independence. It is possible that an employer might take on some of the costs if the animal is of residence. From my own perspective, being a pet parent is full of both joy and work. However, I do not necessarily advocate getting an animal just because you want to do animal-assisted therapy.

If you have one client that you are doing AAT with, what do you do with your animal for the rest of the day in the work environment?

If you only have one client, would it be more feasible to work with someone else who is a handler too, so they can come and go? If it is your own animal, is there a place where the animal can rest for the remainder of the day? Is there another staff person available to monitor the animal? It is a logistical hurdle that is going to differ depending on the clinician. For example, I know clinicians whose entire AAT practice was being run out of their home. There may be another family member who could take care of the animal while the clinician works with a client.

Do you have any examples of challenging situations that you had to deal with in the context of doing animal-assisted therapy in your own practice? How did you deal or overcome that hurdle?

As someone doing animal-assisted work, my experience is specific. This is because I have primarily done it in the context of going to a client's home and working with them and their animal. This would be as opposed to bringing one of my animals into the setting. In that case, their animal was not certified and it was in the context of a research project. You need to be flexible if you are not getting the result that you need with the animal. Are you prepared with techniques to re-engage the animal’s interest? Do you have alternative ways of targeting your goals?

Citation

Antonucci, S. (2020). Incorporating Animal-Assisted Therapy into Speech-Language Pathology Clinical Practice: An Overview. SpeechPathology.com, Article 20422. Available from www.speechpathology.com