Editor’s Note: This text is a transcript of the course, ICF Framework and Narrative-Based Interventions: Lessons from a Care Provider Turned Cancer Patient, presented by Janelle Lamontagne, M.Sc., R.CCC-SLP.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, readers will be able to:

- Describe the role of the ICF framework and evidence-based practice in assessment and intervention planning.

- Explain the importance of incorporating narrative-based practices into the assessment of clients within the medical setting.

- Identify 2-3 ways that narrative-based practice can be utilized to provide holistic, client-centered care.

Introduction

I will be talking about the international classification of functioning framework, evidence-based practice and narrative-based assessment and intervention. As for copyright and permissions, the Bloom's Taxonomy graphic that I'll be showing is released under Creative Commons Attribution license and attributed to the Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. Additionally, I own all the photographs in the course.

I have been working at Brandon Regional Health Center in Brandon, Manitoba since 2013 as a part of a team of three SLPs. I'm fortunate that I've been able to follow my patients across their entire continuum of care. We service 300+ beds, we attend to adult psychiatry, geriatric psychiatry, the emergency department, ICU, acute care and surgery, palliative care, rehabilitation, as well as waiting placement supportive care and chronic care. The reason I list all of those areas is because we have a really unique set up in that the same SLP will follow the patient across all floors. For example, I may initially see a patient in the emergency department, then they end up in the ICU and then they go to rehab. I follow them across all those areas which gives me a really unique opportunity to get to know them. Because of that opportunity, I have been beside my patients while they receive life-changing diagnoses and have also made really difficult life-changing decisions.

While that is one of the reasons I am doing this course, I also have a very personal reason for being passionate about narrative-based practice. Two years ago, my life took a very drastic turn when I went from being the healthcare provider to the patient. On May 10th, 2017, I was unexpectedly diagnosed with a cancerous brain tumor, a grade three anaplastic astrocytoma and was told that I had three to five years to live. When I say unexpectedly diagnosed, I really mean it. I had zero symptoms and I won't go into the whole series of events that led to the diagnosis because that would take way too long. But let me just say that if it was on Grey's Anatomy, no one would believe it. They would think it was too farfetched.

The tumor is located in the premotor cortex of my left frontal lobe right next to Broca's area. As an SLP, initially, all I could think about was of all the locations it had to be there? Why couldn't it be in the occipital lobe or even in the parietal lobe? That would be a little bit better than right in the area that controlled speech and language.

I went in for my surgery within a month of the diagnosis. I had met with my neurosurgeon and he didn't have to twist my arm when he recommended that we do an awake craniotomy to monitor my speech and the movement in my right arm and right side of my face. So, on June 29th, 2017, I underwent a 10-hour awake craniotomy. I was very fortunate that I had a nice surgeon who decided to only shave the part of my head that he had to. I ended up with 29 staples in the shape of a horseshoe.

Since my operation, I have undergone six weeks of daily radiation therapy concurrent with low dose chemotherapy, which was followed by 12 rounds of high dose chemotherapy. I actually finished my last round of chemo this past October. Throughout this whole process, I was struck with the question, how do people with no medical background get through this? When you are diagnosed with cancer or any other life-threatening disease, you instantly go into survival mode. You stop processing nearly everything other than your fear and your grief. Your life is completely upended and everything “normal” is gone in a flash. Your diagnosis, along with the subsequent treatments manifest themselves in so many physical and psychosocial ways and unfortunately, traditional medicine and traditional therapy do a pretty poor job of addressing these areas. So, what can we, as a profession, do to change that?

International Classification of Functioning (ICF)

Speech-language pathologists are to use the International Classification of Functioning framework (ICF) in our assessment and planning intervention. The ICF provides a holistic way of evaluating and supporting a person's functioning in real-life situations. It provides a framework for the SLP to consider more than just the obvious communication disorders. When using the ICF, the SLP begins by identifying body functions that are impaired. Then if possible, body structures that might account for the impairments and functions are identified. Next, the SLP evaluates how these impairments limit a client's ability to carry out specific tasks, particularly those measured by standardized assessments.

Frequently, assessments and intervention for communication stop at this level. The SLP asks if the client has or does not have the capacity to do a task. The ICF however, also considers how the communication impairments may restrict the client's ability to perform actual tasks in real-life activities and participate in a variety of social activities. Many factors beyond the presence of an actual communication impairment may influence a client's performance and participation. Because of the limitations of standardized testing, a communication deficit may not manifest in speech, vocabulary, syntax or conversation with the clinician in a structured situation. Yet it may manifest itself in more challenging life situations. Additionally, other contextual factors may influence performance and participation.

These contextual factors can be of two different types: personal and environmental. Personal factors can include other symptoms or deficits related to the health condition beyond the communication disorder. For example, exhaustion or nausea, comorbid health conditions such as diabetes and psychosocial factors such as fear of the disease, depression, sense of loss, financial worries. Environmental factors can include the available support of family and friends, the attitudes of those family and friends and services and policies related to the actual healthcare system.

Gathering information regarding performance, participation and the contextual factors influencing that performance and participation requires allowing persons to tell their stories in interviews. I'm going to use myself as a case study throughout this whole course. If we quickly look at the ICF in terms of my case, my health condition is cancer. My body functions and structures impacted is the left frontal lobe of my brain. My activities that are impacted are my career, social life, ability to volunteer, even activities such as getting groceries were impacted at one point. My participation was greatly reduced in all those activities and in life in general.

The environmental factor, which greatly impacted me was that my family lives in a different province. My neurosurgeon, radiation oncologist, and medical oncologist are all in Winnipeg, which is a 2+ hour drive away. I made four-hour round trips for every treatment. Both my brain tumor and young adult support groups were based out of Winnipeg as well. It was very isolating living here because it's a smaller rural facility and didn't have as many resources available.

The personal factors which influenced my functioning - and to an extent still do and probably always will - are chronic fatigue and nausea. Since my diagnosis and surgery, I have struggled with anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder from the surgery itself. It's not very fun, to have your skull sawed and drilled while you are wide awake. So, I blame a lot of my anxiety and depression on the fact that my frontal lobe was played with while I was awake. The research actually shows that the incidence of PTSD in cancer patients, which is one in five, is similar to that of combat veterans.

Evidence-Based Practice (EBP)

Current Research

I want to take a deeper look at each part of the triad that forms EBP. As we all know, good research is invaluable. It should form the foundation of everything that we do as SLPs. If we don't stay up to date on research, we really have no business practicing. That being said, when we think about research, we have a tendency to think about what is quantifiable. We tend to equate research with graphs, statistics and measurable results (e.g., Doing x intervention with y population should result in z outcome).

While quantitative research is invaluable, sometimes it isn't necessarily practical when working in certain settings or with certain patients. Have you ever had a textbook patient? I've worked with hundreds and hundreds of clients and have yet to meet one that follows all the rules. Due to core morbidities, our patients often do not meet the checklists of the experimental groups and research. Therefore, even meta-analysis, the gold standards of research don't necessarily 100% apply to our patients. If research evidence was the end-all-be-all to assessment and intervention, we would be out of work. A well-designed task analysis of assessment and treatment could pretty much do our jobs for us.

Since I have used myself as a case study, let's look at the research evidence for patients and patients with brain tumors. The majority of the literature on brain tumors and speech-language pathology focuses on types of brain tumors, characteristics of related speech and language impairment and strategies for addressing the impairments. However, brain tumors may cause a wide range of neurological dysfunctions including aphasia but the treatment strategy for this population is still understudied. Furthermore, cancer-related language disorders are considered secondary to brain cancer in the medical field and therefore are undertreated.

Just a side note, I'm really excited that there's starting to be more information out there on the way chemo brain affects patients and what the role of the SLP actually is in that population because that's something that I feel hasn't really been looked at. I'm currently taking a 32-hour course and it has some really good information on treating cancer patients. All the research evidence that I just shared focuses on the assessment and treatment of language disorders in patients with brain tumors. But what about the psychosocial support? In a meta-analysis of over 6,000 articles on treatment of brain tumors, Ford and colleagues reported that only 1% addressed the broader psychosocial needs of the patient and the family. That's a bit disheartening.

Clinical Expertise

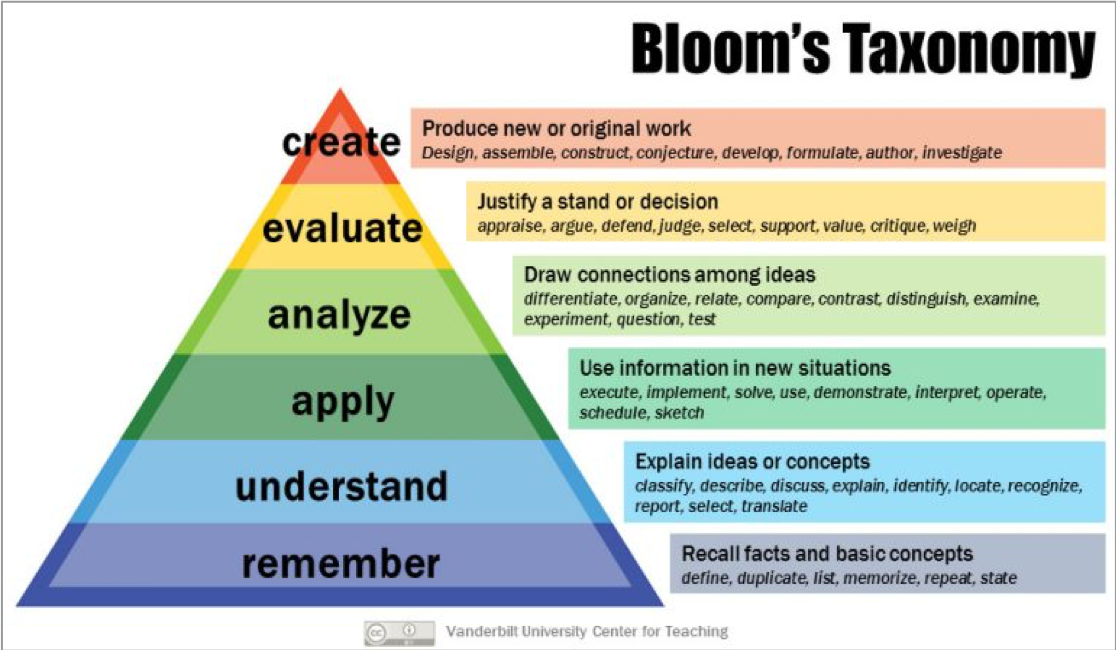

Let's move on to the second piece of evidence-based practice, clinical expertise. SLPs are required to have a master’s degree to practice. When we look at Bloom's Taxonomy (Figure 1), at a minimum, we should be at the second level from the top which is ‘evaluate’.

Figure 1. Bloom's taxonomy.

Our justification shouldn't just be, “Well, I read this article once.” We need to think critically. As clinicians, we have the responsibility to take the case history and prior medical history of our patients, to talk to our patients about their goals, analyze our mental library of knowledge pertaining to this situation, which includes previous experiences with similar populations and justify why we are doing what we are doing. All of these factors converge into clinical expertise.

My example of how this pertains to my case is in regards to my neurosurgeon's clinical expertise. As I was asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis, much of the research evidence would suggest a wait and watch treatment approach - wait until I start having seizures, migraines, cognitive decline or motor problems before offering surgery. Brain surgery is always risky, so the wait and watch approach is a conservative treatment plan. However, when my surgeon looked at my overall health, the location and size of the tumor, and my age, he suggested surgery and possibly chemo and radiation right away. He then recommended an awake craniotomy in the intraoperative MRI suite so that he could be more aggressive as they would be able to monitor my speech, language, and motor movement. Throughout the whole appointment, he provided research evidence that used his own clinical expertise to justify his suggestions and develop an operative plan specific to me.

Client Values

Let's look at the third section of the triad and the one I'm the most passionate about. The third part is client values. What matters to the client? This should be one of the first questions that any patient is asked after a diagnosis. What matters to you? However, this piece is often missed in healthcare or seen as less important than research evidence and clinical expertise. As SLPs, we pride ourselves on helping people communicate, giving them a voice and helping them regain their voice. Sometimes though we are really bad at listening to what they want to tell us.

As a whole, healthcare professionals tend to focus more on their own agendas and goals for the patient than the goals of the patient himself. As a patient and a healthcare provider, I was able to advocate for my values throughout my journey whereas many of our patients either don't have knowledge of the healthcare system or are too intimidated to speak up for themselves, so their values may be dismissed. How can we change that?

Relationship Between the ICF and EBP

First, let’s go back and see how the International Classification of Functioning and evidence-based practice converge. That joining will guide us into narrative-based practice. To review, the World Health Organization International Classification of Functioning begins to look at functioning in terms of diagnoses, affected body structures and the impact they have on a person's activities and participation. It then investigates the environmental factors and personal factors that influence participation.

Then, we have evidence-based practice and each part of EBP corresponds with a certain amount of ICF. So, current research pertains to the health condition, the body functions and structures and activities. For example, in my case, research would be geared towards brain cancer, the areas of the brain impacted and what impact the affected areas have on certain tasks. The current research would, hopefully, also provide information on treatments to improve those tasks. Client values looks at participation, environmental factors and personal factors. So, as a patient, I just want to get better and be able to participate in my life fully. But I need people to recognize the limiting factors - anxiety, depression, PTSD, fatigue, nausea, finances, family support and access to additional psychosocial supports. Lastly, all components of the ICF should be integrated by our clinical expertise.

What is a Narrative?

Now that we have an understanding of how the ICF and evidence-based practice come together, how can we use narrative-based practice to assess our patients in a way that uses both? A narrative, according to the dictionary, is a way of presenting or understanding a situation or series of events that reflects and promotes a particular point of view or set of values. When I read this definition, a few keywords stick out to me: understanding, events and values. Narratives are the stories we tell ourselves and others based upon our values and our understanding of certain events that occur.

Here is a simple scenario to highlight this. Pretend you're driving to work one morning and this other vehicle come speeding up behind you, pulls in front of you and proceeds to cut you off. My knee-jerk reaction may be to think, “Look at that person. She just cut me off. She obviously has no care for her safety or the safety of others. Maybe she should've left her house earlier this morning if she's in such a rush.” That would be my narrative of the situation. The driver's narrative however, may be that her three-year-old just fell off the play structure at daycare and is being taken by ambulance to the hospital and she needs to get there as fast as she can. She may even be completely unaware that she was speeding or that she even cut you off. The point is that narratives are subjective based upon your knowledge, your ideals and your interpretations of what is presented to you. There is increasing awareness of the value of narrative-based practice in client-centered care and speech-language pathology.

Narrative-Based Practices

Narrative-based practices in which SLPs listen to clients personal narratives of their lived experiences enable SLPs to gain an understanding of factors that influence a client's performance and participation in a real-life setting and to develop intervention programs that consider the needs and values expressed by the clients.

Narrative-based practice can seem quite daunting in terms of time management. However, it can lead to better or functional outcomes in a shorter period of time. The easiest way to incorporate narrative-based practice into assessment is through obtaining your case history. This doesn't replace the need for a thorough chart review as the patient's perspectives and knowledge of their medical histories may differ greatly from the medical teams, but it will provide a lot of insight into what parts of the patient's medical situation are the most important to him or her. Furthermore, you will learn the areas of rehab the patient is actually interested in.

The Compliance Conundrum

I want to segue into something that I'm very passionate about and is a problem that has occurred more times than I would like to admit since I've been working. In the past I've had patients, and I am sure you have too, who were labeled as noncompliant by the medical team. In most cases, the noncompliance could be categorized in one of two ways. Either the patient didn't listen to the plan of care or the patient was viewed as unmotivated. Sometimes this perceived noncompliance and lack of motivation results in patients not receiving the best of care from their medical team and this is heartbreaking. We are letting our egos get in the way of providing quality care. We, meaning the entire medical team is often forgetting a key piece of the puzzle: patient autonomy. It can be so easy to get caught up in this idea that, “Well, they're not participating in therapy the way that they should be, so they're not motivated. They don't want to get better.” Well, what are we doing in therapy that they find unmotivating? We shouldn't be doing anything in therapy that the patient doesn't find motivating.

To give you another example, I myself have made so many perceived bad decisions since my diagnosis. I went to a music festival the day after my 29 staples were removed from my head. I have put myself at risk of infection by getting multiple tattoos since diagnosis. I've traveled extensively across Canada and the US, everywhere from Niagara Falls to Las Vegas to San Francisco to Newfoundland to Boston, all with a compromised immune system. I even did a road trip from Saskatchewan to New Mexico while I was on chemo. I went back to work one month after completing my chemo. So why was I so noncompliant? Why was I willing to compromise my health in so many different ways? Well, the memories that I've made far outweigh the risks for me. And fortunately, I've had a medical team that not only respected but supported my choices. My medical team asked me the key question that I would really like you remember from this course. “What matters to you?” My medical team asked me that question and it had a tremendous impact on my journey.

Ethnographic Interviewing

Let's discuss additional questions that are important to ask in narrative-based practice. One of the ways of obtaining information for narrative-based practice is simply through ethnographic interviewing. There's a lot of information available on this topic so I am going to highlight some of the questions and types of questions that I find the most useful.

Descriptive Questions

There are five types of descriptive questions. First are grand tour questions which are intended to encourage a person to talk about their broad experiences. They tend to ask a person to generalize how things usually are. For example, “Tell me about a typical day with your family.” That would be a grand tour question.

Mini tour questions are the same as grand, but they ask the person to describe a specific activity or event. They usually follow responses to grand tour questions. For example, “You mentioned that you like to go on family outings in the afternoon, can you describe an outing that you've gone on?” The question relates to the grand tour question, but it gets a little bit more specific.

Example questions are more specific than both of the tour questions. They take some idea or experience and ask for an example. If the patient says, “I'm just not myself anymore.” You could respond with, “Give me an example of what the old you used to do.”

Experience questions ask about experiences in a particular setting. “Tell me about some of your experiences with your oncologist.” They tend to get at those atypical occurrences. You will get the extremes, either good or bad. Consequently, experience questions are best asked after numerous grand tour and mini tour questions so that you, as the interviewer, have information about what are typical behaviors for this person and are not under the assumption that this atypical experience is the norm.

Lastly is native language questions. In medicine and in speech-language pathology, there's a lot of jargon. We need to make sure we understand how people are using words and that people understand how interviewers and other professionals are using the same words. Native language questions are useful for these purposes. They ask people to describe the terms and phrases they would most commonly use which allows us to understand what these terms mean to the person. For example, “You said you don't want palliative care, what does the word palliative mean to you?” Many people believe that palliative care means that you're imminently dying, there's no hope and basically the medical team has given up on you. However, that is not at all the case. Palliative care is more for quality of life and symptom management than anything. Here is an example from where I work. Our hospital is divided into 2 centers – a general center and the A.B. Center. One floor of the AB Center is actually the palliative floor and the rehab floor is below that.

Once people are medically stable in the general center, they are transferred over to the AB Center for rehab. We have to be very careful when we say that they're going over to the AB Center because it's a small community and nearly everyone who is a patient has known somebody that goes over to the center for palliative care. We have to be very careful of telling the patient that we are transferring them over to the AB Center because they may interpret that to being transferred over to palliative care and they are dying. Again, that is an example of why it is so important to understand what people's interpretations are of certain words and certain phrases.

Structural Questions

Another type of question for ethnographic interviewing are structural questions. There many different types and get to more of the bones of what the person's thinking and what they're feeling because they require a specific answer.

- Strict Inclusion - X is a kind of Y (e.g., “What kind of things did the doctor say.”)

- Spatial questions - X is a part of Y (e.g., “What are the steps to your treatment regimen? What steps do you go through every time you go for chemo?”)

- Cause and Effect - X is a cause of Y (e.g., “What things are causing you to feel depressed? What has been the result of telling your family how you feel?”)

- Rationale - X is a reason for doing Y (e.g., “What are your main reasons for wanting to come down to therapy?” “What are your main reasons for skipping PT today?”)

- Location for Action - X is a place for doing Y (e.g., “Where are the places that you like to spend time with your friends? Where are the places that you feel most comfortable?”)

- Function - X is used for Y (“What items do you use to make eating easier?)

- Means-End - X is a way to do Y (“What are the ways to inform your family how you are doing?” “What are the ways to keep you from getting sick? What can we do to help A, B and C get better?”)

- Sequence - X is a step or a stage in Y (e.g., “What are your steps for getting ready in the morning?”)

- Attribution - X is an attribute of Y (e.g., “What are the attributes of the people who have been the most helpful for you?”)

There are many different questions that can come from these formulas. I gave one or two examples for each type, but they are limitless.

Asking the Right Questions

Not all questions are created equal. There's a fine line between interviewing a patient and interrogating a patient. While we want to obtain as much information as possible, it is important to not ask too many questions and not ask multiple questions at a time. When interviewing a patient, it is helpful to start broad by asking questions such as, “What does a typical day look like for you?” or “How has your life changed since you were diagnosed with cancer?” Based on their answers, you can show the patient that you are listening attentively by restating a theme that they have mentioned and probing further into that topic. For example, “You mentioned that you haven't been able to work. How has that affected you?”

Personally, since my diagnosis, I have been seeing a psychosocial oncology clinician and he has been really good at asking me the right questions. As an SLP, I like to think that I know where people are going when they start asking me questions and what their agenda is but he's caught me off guard several times. He has picked out themes in my thoughts and behaviors that I was completely oblivious to. I remember one particular session when I struggling with my prognosis of three to five years and I was telling him that it was difficult to find the balance between pessimism, realism and optimism. I felt that if I accepted my prognosis then I might as well just give up then and there. He asked me a question that I will never forget: “What does hope mean to you?” I hadn't even realized that our whole discussion up until that point surrounded the concept of hope and my fear to hope for a future. If he hadn't been listening for a theme in what I was saying, I'm not sure how the session would have ended up. I'm not sure that mentally and emotionally I would be in the place that I'm in today. So, by starting broad and restating and probing certain themes, the information you can obtain during the interview is limitless.

It is important to remember, however, that silence is also a very powerful tool. We have to allow our patients time to process our questions and formulate their responses, especially when we are dealing with patients who have been given really bad information or diagnoses or are going through chemotherapy and radiation. I know for myself, if my processing had been tested right after I was diagnosed, I would have been in trouble because I wasn't processing things as quickly.

Your mind has so much going through it that it kind of weeds out what seems to be less important. We really have to give that extra time to allow individuals to consider our questions and form their responses. Also, the nice thing about silence is that sometimes it makes people uncomfortable and gives people the urge to break the silence. We can use that to our advantage as well.

Words of Caution

Now that we've discussed some of the types of questions to ask, I'd like to provide some words of caution. First is listen to learn, not to judge. Our foremost priority should always be our patients' well-being. Our intervention choices should never be colored by our personal biases. When we are asking for people's narratives, sometimes we hear information about them that could potentially color our judgment of their character and we should never allow that to affect our approach to providing them the best intervention possible.

Secondly, avoid “why” questions. Why questions can come off really harsh and critical. Instead of asking your patient why she feels a certain way ask what has caused her to feel that way. That takes the point of the question off of her and on to “what” – “What has caused you to feel that way?”

Third, we should never ask questions just because we're interested. Information that is obtained should be assessment or intervention based. Sometimes patients just really need to talk to somebody and you'll be that person. You'll learn more information than needed and that's okay, but we shouldn't go fishing for information just out of curiosity sake.

Fourth, when dealing with people in vulnerable, emotional states, it is important that we remember our scope of practice. As empathetic care providers, it can be so tempting to try to fix things by giving advice. However, we must be cognizant of our roles and make the appropriate referrals to other team members as needed. I know I am on the phone with our social worker almost weekly to have them help out with those areas.

Case Study

So now that we've discussed what types of questions to ask, I'd like to share my experience as a case study to show the potential differences between the narrative of a medical team and the narrative of a patient. This is information that could be pulled right out of my medical chart and is the narrative that my medical team would have.

I am a 31-year-old female with prior medical history of acquired Von Willebrand disease, which is a bleeding disorder. I was diagnosed with a grade three anaplastic astrocytoma in 2017 at the age of 29. I had a debulking craniotomy June of 2017, followed by 30 radiation treatments concurrent with low-dose temozolomide which is a type of chemotherapy. That was followed by subsequent high dose chemotherapy for 12 months, monitored by three-month MRIs which have remained stable. My overall prognosis was three to five years. Again, that is the medical team's narrative.

Personal Narrative

Here is my story. While I'm sharing this, I would like you to pay attention to the differences between the narrative of the healthcare team versus my narrative. I'm going to share this story as if I were the person who was asked the right questions. Here's a little background information. I have a rare, severe bleeding disorder called acquired Von Willebrand disease. Basically, my blood doesn't clot on its own. The machine that’s doing the testing actually times out before my blood clots. On April 29th, 2017, I randomly had a vein rupture in my upper arm.

Because of my bleeding disorder, I ended up in the ER for treatment. I reacted to the treatment and ended up back in the ER four days later with a severe migraine. Because I had just had this spontaneous vein rupture, my hematologist was concerned about a brain hemorrhage. He ordered a CT scan – and boom - brain tumor. I was 100% asymptomatic. Everything felt so surreal. How did I have a golf ball-sized tumor in my head and not know it? Especially in the area of the premotor cortex and Broca's area. I was told at that time that it was likely low grade and I should be fine once it was removed. I shouldn't require any chemotherapy or radiation and that it was likely benign.

A few appointments and MRIs later, I was in for a 10-hour awake craniotomy. I honestly don't remember anything from the time I was diagnosed until my surgery. It's just a big blank. I must've just gone through the motions. I know I went to work until June 23rd because I have reports I wrote during that time. I'm not sure how accurate they are, but I know I worked up to six days before surgery. But I have zero recollection of that time. I think it was just processing.

Back to my brain surgery. For the surgery, I was given IV sedation (similar to going to the dentist) and local freezing to my scalp. I remember the sounds of my head being bolted to the table. I remember the feeling and the noise of the bore holes being drilled and my skull being sawed. Like I said earlier, to this day, I have PTSD from that. I saw a psychologist for exposure therapy which has helped dramatically. I no longer have a panic attack or feel like I'm going to be sick when I hear sawing or drilling.

When I went back to work after 18 months off, of course they were doing renovations on the floors. There were several times when I had to leave a floor as soon as I heard a drill or saw turn on because I was going to either burst into tears or pass out. It's much better, but I still don't enjoy those sounds and they still make me feel quite sick.

The rest of my surgery consisted of the surgical team mapping my brain. I was connected to all sorts of electrodes and was asked to speak and move my right arm throughout the operation so that everything could be monitored. I had actually told my neurosurgeon that I didn't care if my arm became paralyzed during the surgery as long as he got the whole tumor. In fact, I didn't tell him when I could feel him probing the area that controlled my arm. But the electrodes on my arm gave me away though and he knew I was lying. (I don't know if any of you watch the Show House and how all patients lie, but that is what my neurosurgeon said to the resident as he's working on my brain, “See patients lie. I was affecting her arm.” We talked about politics, work, you name it. At the point when they asked me about work and I said, “Oh, I do videofluoroscopic swallow studies quite often” they decided that they didn't really have to worry about my speech that much longer.

Ten hours later my head was stapled shut and I was taken to the recovery room. Despite neuro checks every hour throughout the night, I felt great the next morning and I'm not exaggerating at all. I actually said the next day, “Oh, I don't think I'll have to be off work for six weeks. I think I can go back next week. Little did I know. I thought I had come out of surgery with no deficits. Well, that was until I tried to send my first text. That was the moment that I realized that I had right neglect and apraxia in my right hand. These deficits became increasingly apparent when I was no longer able to print my name and lost my cutlery at every meal. I nearly shoplifted once I got home because my mom and I went to get groceries and I picked up a couple of things in my right hand. I completely forgot about them and went to leave the store. I don't know that brain surgery would have been a good excuse had I been caught, but luckily my mom caught me before I had to find out.

Four days post-surgery, I was discharged home. The three weeks following my surgery went really well. I was sure that the tumor was gone and that life would resume to normal. I just had to wait the required four weeks before returning to work. I spent time at the lake and joked about how lucky I was to have a month off in the summer. Then I got the call that my neurosurgeon wanted to meet with me. What followed were words such as cancer, chemotherapy, radiation, life expectancy, fertility preservation, et cetera. I remember crying the entire two-and-a-half-hour drive home from the hospital and pretty much every day after that for a while. I would fluctuate between anger and sadness and apathy daily. At times, I wondered what was even the point of treatment? I'll be dead in three years anyway. But I proceeded.

Two weeks later, treatment started. Brandon wasn't able to offer the type of radiation treatment I needed, so I made the five-hour round trip to Winnipeg every day for six weeks. My hair fell out and I had radiation burn on my scalp. I'm so lucky that I didn't experience some of the headaches that other people do, but my fatigue was awful. With every step I took, it felt like I was dragging around 100-pound weighted blanket.

Chemo also kicked my butt. I had five days of treatment, followed by 23 days off for 12 months. I needed platelet transfusions and ended up in the hospital for IV hydration. One of the hardest things about chemo was that I was off work and so I had five days of chemo, which I felt horrendous. And then the following week I would start feeling a bit better and I have one week of nearly normal and then it would start over again. During that one good week, I really felt a loss of identity. If I wasn't an SLP, what was I? What was my purpose? I had just gone to school for six years to become a speech pathologist. I didn't know anything else and now that's taken from me. What am I supposed to do with my life? I needed something.

So, I began fostering puppies for the Humane Society. I was already a foster failure with my first dog, so I should've known I'd end up keeping another. But I think my stats are overall pretty good. I've only kept two out of seven. I finished chemo the end of October 2019 and throughout that whole process, my goal was to return to work.

I rushed back to work within a month of treatment and that's when I crashed. All of this stress and anguish and pain of what I had gone through hit me. I couldn't function. That's when I actually started seeing a psychologist to help me process and grieve everything that I'd been through. I am now in a much better place and I'm so happy and fortunate to be back to work full time. That being said, it has been very emotionally taxing to work with other cancer patients or those with terminal diagnoses. However, I also find it so very rewarding because I feel like I have a unique perspective. I've been given a glimpse into the other side.

That brings us to this moment. Why did I tell you all of this? I shared my story because narrative stories are important. In order to relate to our patients and provide the best services possible, they have to feel like they can speak to us. There is a quote from Brene Brown, “We're wired for story. In a culture of scarcity and perfectionism there's a surprisingly simple reason we want to own, integrate, and share our stories of struggle. 'We do this because we feel the most alive when we are connecting with others and being brave with our stories.” I know that for me, as a patient, telling my story has been freeing. It also can be very scary and the amount of vulnerability you feel when you tell your story can be overwhelming. But it has helped me tremendously come to terms with everything and helped me move forward. And I truly believe that we need to offer our patients that opportunity as well. As a health care provider, hearing the stories of patients allows me to connect, empathize, and find meaning in their actions.

I'm sure you could see from my narrative that my hospital records leave a lot out. They leave out the decision, the struggle I went through when I had to decide in less than 24 hours whether I was going to preserve my fertility and in doing so delay my cancer treatment. They left out how hard it was to tell my little brother and little sister my prognosis. They left out the guilt of being a patient and the guilt of what you're putting your family through. I know it's completely irrational, but that is a very real part of being a patient.

When I look back at how I practiced prior to being a patient, I think of all the times I told patients when they were struggling, “Just lean on your family. Your family wants to be there to support you.” Now, I could just slap myself because that's the last thing you need to hear as a patient. You are feeling so much guilt and that's really not a helpful answer.

Therapy Ideas Guided by Narrative-Based Practice

Let’s discuss the ways we can use narratives in therapy. Narrative-based practice is essential to providing holistic client-centered care. We need to treat the patient, not just the disease. Narrative-based practice informs us of client values and guides us into establishing treatment goals, addressing participation and functioning in daily activities. Furthermore, listening to patient's stories provides us with insight into environmental, psychosocial and motivational barriers to success. Because client goals are so personal and individual, it is impossible to provide specific tasks that can be used with all patients. But I can give you some activities that I, as the patient, would find meaningful if my ability to communicate was limited.

Use What’s Important to the Patient

- Brainstorm a bucket list - What are the things the person wants to do before it's their time to go?

- Recall the names of family members and friends

- Formulate lists of questions for health care providers - This is an activity that is very important because, in my experience, it is really difficult to remember everything you want to ask your doctor in certain appointments. Have that list of questions and if we, as therapists, can help them formulate those lists, that's huge.

- Script important conversations with friends and family

- Develop outlines for a memoir

- Voice or video record special memories

- Plan their legacy

- Describe the occasions behind family photos

These are just the tip of the iceberg. There are so many other ways we can incorporate narrative-based practice into intervention. We just have to be willing to take the time to listen to our patients.

Facilitate Active Participation in Life

- Help organize an anniversary supper

- Help sequence steps to go bowling - That's actually something that I've recently done with a patient and that was his goal. When he goes home, he wants to be able to go bowling again. So, we've been sequencing what you need to do to go bowling.

- Practice calling a friend to invite them to visit - We want to make sure that we are allowing our patients to participate as fully as possible in their lives.

- Follow a recipe to bake a birthday cake

- Identify factors limiting participation and brainstorm solutions

Ask the patient what are some of the things that are limiting their participation. What are some of the things that are making it hard on life and find different solutions. Sometimes patients get caught up in, “Well, I can't do this anymore and I can't do that anymore.” But there are actually solutions to help them. We just need to think outside the box a little bit.

Here are a few examples of when I have actually used the question, “What matters to you?” and how I've incorporated patients’ answers into therapy. The first example is a patient that was in the ICU for quite a while. She had respiratory failure and had a really difficult time being weaned off the ventilator. She was just kind of multiple organ failure, septic, and just all-around a very unhealthy person by no fault of her own. She was always this very spunky lady and I could always count on her to make me laugh when I saw her. When I was first assessing her, I asked if I could take her teeth out to clean them before we did the swallow assessment. I didn't realize that she still had her own teeth and she said, “Well, that would be quite nasty of you.” That was the type of personality she had and who I was expecting to see this one day when I walked into her room. What I found was her sobbing and completely distraught because she felt so ill and for such a long time. She just kept saying, “You know, I'm just done. I just wanna die, I can't do this anymore.”

I tried to console her as much as I could and I wasn't getting anywhere. Finally, I asked her (and I should have asked it sooner), “What matters to you?” And she instantly said, ''My husband. He's such a good man and he has dementia and it's not fair that he has dementia. Right now, he doesn't know where I am and he doesn't know what's going on. He will be so scared and I worry about him.” I asked her where her husband was. It turns out that he was actually in our center for geriatric psychiatry because she was the caregiver and when she was hospitalized, there was no one able to take care of him at home. For therapy that day, once we got through everything, we wrote a note for her husband. She had macular degeneration, so she dictated and I wrote it for her. That was our therapy - writing a note to her husband that I could take up to the floor and read to him, get his response, and bring it back to her. So, just asking that question, “What matters to you,” made a tremendous difference. It went from a completely hopeless therapy session to one where we made meaningful progress and a meaningful difference in her life. After that, she was her happy, spunky self. I'm happy to say that she made it out of there.

Another example of using the “what matters to you” question and incorporating it into therapy, is I had this gentleman with a stroke and severe Broca’s aphasia. He couldn't even say his name when I first met him. We were trying to figure out a way to help him participate more fully in life. So, I asked him, “What matters to you?” Not in as many words, we had to do a lot of gesturing, he told me that he wanted to be able to go out for lunch or breakfast with friends and to keep up to the conversation. Our therapy was printing off all the menus of all the restaurants he went to with his friends and practiced ordering food.

I was the waitress and we role-played. I would say, “Good morning, sir, how are you today? What can I get you to drink?” He would verbally tell me what he wanted to drink and we did that for quite a while. This was a gentleman who didn't really see the point of therapy at times. He had very poor insight in self-monitoring, but this was something that was hugely important to him, to be able to go out for coffee with the guys.

Summary

In summary, the International Classification of Functioning framework and evidence-based practice encompass essentially the same concepts. We must move past traditional assessment and intervention towards participation and performance in a real-world setting. Narrative-based practice allows us to do that. It allows us to ask the most important question in my mind and healthcare and that is, “What matters to you?”

I'd like to finish with a quote: “All sorrows can reborn if you put them into a story or tell a story about them.” I really like the way that sums up narrative-based practice.

Questions and Answers

The ethnographic interview questions are used for more than just assessing the patient, correct?

Yes. I personally feel that it can be used kind of as a dynamic assessment throughout any therapy session actually. It's not just to be used just in the assessment phase because our patients change and their wishes change so frequently that if we stick to what our initial assessment says, we're not paying attention to what we need to.

I don't have any questions, but just wanted to say great job. This was an incredibly practical training full of immediately implementable tips and strategies. Thank you for sharing your story with us. You are a wealth of knowledge and incredibly inspiring person and therapist. I was certainly thrilled to see you were the presenter today.

Oh, thank you.

You do not mention use of standardized measures, so how do you assess deficits in conversation, vocabulary, syntax et cetera or is that not important?

That is definitely important. I do mention at the beginning that as part of the ICF we do use those standardized assessments. But a great supplemental part to look at participation is the narrative-based assessment. I definitely use the CLQT and other assessments otherwise how do we know really what we're focusing on? But the narrative-based part is to find out what matters to the patient in order to focus our therapy towards treating those deficits in a meaningful manner, if that makes sense.

Do you include any caregiver training and if so, what do you like to see as a focus?

It honestly depends on the patient and the patient's wishes as to how active I am with caregivers. Caregivers obviously play a very important role. But I also know as a patient that sometimes I just wanted therapy on my own. I didn't want to have to burden my family members. It depends on the patient, I would say. If the patient's open to caregiver training, I think that's wonderful. With the gentleman I mentioned with the stroke, his wife came and sat in with us for one session each week minimum just to carry over any of the recommendations and help interpret the patient because at times I didn't know what he was like pre-stroke. So, she would tell me what he really enjoyed doing and ask if “such and such” was something we could incorporate into therapy? So, ultimately, I think you have to use your clinical decision making on how much to include the caregivers based upon the patient's wishes.

Are there ever times that you may ask a caregiver, and I don't know if this is outside of our scope of practice, what they would like?

It depends a lot on whether the patient has the competency and the capacity to make their own decisions. I have had patients who aren't able to make their own decisions. So, a lot of that does fall more on the caregiver. Yeah, that's a tough one. I don’t really have an answer for that.

Have you ever had a situation where, depending on the communication abilities of a particular patient and you're getting a good feel from the family that they want what’s best for their loved one, that you would ask the family what would the like?

That gets dicey too because sometimes the families goals aren't the patient's goals. As long as I think a patient is competent and has the capacity to can make their own decisions, I would never go to the family without their permission. I think that's stepping over boundaries and taking away their autonomy.

What is the first thing you do when you meet a patient for the first time? Use your narrative assessment and ethnographic interview to collect communication skill data? How long are your sessions? It seems narrative assessments can be time-consuming as people do love to talk about themselves.

Yes, you're exactly right. The first thing I do is try to establish rapport with patients. I introduce myself and start asking the grand tour questions. I find that if we jump right into the standardized assessment, that can be a little off-putting for patients. So, I usually just try to get some of their personal narrative first. I am fortunate with where I work that I don't have specific time limits for working with patients. As we all know, some people really do like to talk. So, one of the little tricks I do is to tell one of my colleagues is f I'm not out of the room in 15 minutes, they need to page me overhead. That way you're not offending the person by having to leave, but you can actually move on to the next person.

How have you graciously managed talking to and treating patients who have not yet received their prognosis or diagnosis, but just went through a resection or biopsy?

Oh, that's a big one. I find it so hard when I know the information and the patient isn't informed yet. It's a very, very difficult situation to navigate because sometimes there's a pretty big delay between the pathology results coming back and the healthcare team knowing what's going on before the patient finds out. I usually just use hypothetical scenarios and say, “You know, we don't know what's coming. We don't know what is going to happen, but if A, B and C were to happen, here are some of the things we need to start looking at or start working towards.” Then I just give tidbits of information because it's very overwhelming as the patient with how much you're given. I don't like to bombard people, but I also like to give them a little bit of preparatory information because there's nothing worse than being in that limbo and not having a plan.

Citation

Lamontagne, J. (2019). ICF Framework and Narrative-Based Interventions: Lessons from a Care Provider Turned Cancer Patient. SpeechPathology.com, Article 20333. Retrieved from www.speechpathology.com