Editor's Note: This text is a transcript of the course Executive Functioning for School-Age Children: It's More Than Being Organized, Part 1, presented by Karen Dudek-Brannan, EdD, MS, CCC-SLP.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Define executive functioning and it’s impact on academic, social, and emotional functioning.

- List 2-3 common challenges multidisciplinary teams face when supporting executive functioning.

- Describe barriers to generalization that occur when utilizing common service-delivery models.

Introduction

I've been working with school-age groups since I started in the school systems. When I took on the role of a school Speech-Language Pathologist (SLP), I felt quite overwhelmed by the multitude of things to address in language and understanding my role in literacy, as well as being on the school team. Adding the executive functioning piece made it even more challenging to grasp how they all fit together and what my specific role as an SLP entailed, along with determining effective intervention for both of those aspects.

So, when it comes to this topic, there's a lot to cover. In mentoring clinicians, I take a structured approach. We start by identifying what we're actually addressing, the skills involved, and how we, as clinicians, can develop solid operating procedures and protocols to support these skills. Once that foundation is in place, we move on to working effectively with our teams. The initial step is gaining a solid understanding of the problem, the skills, and how the symptoms manifest and recognizing common challenges in how school teams are set up.

This guidance is applicable not only to those directly working in schools but also to those dealing with school-age populations in various settings. To start, let's look at some common symptoms you might encounter when working with a school-age population. These symptoms often arise in students dealing with a range of academic, social, and emotional skills, making it challenging to pinpoint where to start with intervention. We aim to categorize these symptoms based on the descriptions provided by teachers when referring students.

Attention

Diving into one of those key categories that frequently crops up is attention. Many students, especially those grappling with language issues, often face additional learning challenges, and this often manifests in inattentive behaviors. These are the children that, when teachers, parents, and others interact with them, notice signs of inattention or being off-task. On the flip side, there's the possibility of hyper-focusing, where they might not be paying attention to what they're supposed to but are intensely focused on something else. This can make transitioning from one activity to another a real struggle because they get locked onto one thing. So, that's a significant cluster area to monitor.

Learning

Considering the associated learning issues is also critical. When we connect this to aspects such as language, which is a common focus for SLPs, we often encounter difficulties in problem-solving and inferencing. This challenge extends beyond the academic realm and seeps into various functional areas. It's not just about understanding concepts in school; it also extends to everyday tasks like knowing how to climb stairs or following instructions from parents, such as cleaning their room. The struggle is very apparent when it comes to problem-solving and making inferences during tests at school.

A recurring theme is the difficulty these children face in learning from their mistakes. Reports often highlight situations where they go through a lesson, yet the next day, it seems they've forgotten what was covered. This ties into a larger issue of poor generalization, a common thread we observe with language, academics, or social skills.

Behavior

Another significant area is behavior issues. One notable pattern is emotional reactions not aligning with a situation. There's a struggle in gauging what constitutes a big problem versus a small one. Something seemingly minor might trigger a disproportionately huge emotional response, indicating a challenge in understanding the emotional magnitude of situations. This can manifest as anxiety, particularly in new situations where the child might need that extra push to step out of their comfort zone.

Moreover, there's the classic task avoidance. Whether it's something new and unfamiliar or just a task perceived as difficult or uninteresting, we often see students avoiding it. This can range from reluctance to engage in new or unfamiliar activities to outright refusal to tackle challenging or perceived boring tasks, like repetitive math assignments. Writing assignments, a significant challenge for many, often become an area where this task avoidance is prominently observed. Reports may mention instances of refusal, leading to labels like defiance, but it's essential to understand the underlying challenges these students face in these situations.

Organization

The organization aspect, especially in the realm of executive functioning, is a key area that often comes to mind. It's one of the most common external symptoms associated with executive functioning challenges. Take, for instance, the student who's consistently missing assignments and deadlines, frequently misplacing their belongings, and struggling to keep track of where everything is. A poor sense of time management is evident, as they may not be fully aware of the passage of time while engrossed in an activity, leading to delays and taking longer than expected to complete tasks.

This lack of time awareness can result in falling behind the class, still gathering their materials while others have moved on to the next assignment. There's also the challenge of estimating how long tasks will take, a distinct skill from sensing time during a specific activity. Planning ahead becomes a hurdle, whether it's realizing that there are 10 minutes left in class or understanding when it's time to catch the bus. All these factors contribute to what often gets labeled as disorganization, as these students struggle with coordinating and managing their tasks and responsibilities effectively.

Social

Finally, social executive functioning skills or social skills often come up. While it might not be immediately associated with executive functioning, when we consider the array of skills mentioned earlier, such as emotional reactions and attention, social skills also come into play. For instance, there are instances where a student may not actively participate in conversations. They might struggle to join in, make comments, or follow the flow of a discussion. Alternatively, if they do engage, it might come off as blurting out, whether in a classroom setting or during informal conversations with peers or adults. These individuals may tend to make off-topic comments or give the impression of dominating the conversation.

There's also a phenomenon known as info-dumping, where they share extensive information on a topic they're passionate about without necessarily gauging the interest or attention of their conversation partner. Moreover, there could be difficulties in interpreting others' actions or understanding how they come across to those around them.

These Behaviors Do Not Indicate Someone Is...

When engaging in the above behaviors, do they take note of how others are responding? These are the typical clusters of behaviors we frequently encounter and are likely familiar to you. You may have students on your caseload exhibiting some or all of these traits, perhaps perfectly describing a couple of students you're currently working with. So, what do these behaviors mean? Unfortunately, they often get mislabeled.

These behaviors do not imply laziness, even if there's a tendency to avoid certain tasks. However, this interpretation is unfortunately common. They also don't suggest someone is unintelligent or incapable. Additionally, it doesn't mean they cannot improve these skills, despite the challenges they may present as learning problems and certain cognitive difficulties. Even if they struggle with forming social relationships and, in some cases, appear disinterested in interacting with peers, it doesn't necessarily indicate a lack of concern for friendships, a disinterest in having them, or a lack of empathy. Even when they may come across as rude or not considerate of someone else's feelings, it doesn't necessarily mean they cannot empathize with others.

These Behaviors Do Mean...

If these behaviors don't point to the mentioned misconceptions, what do they signify? Generally, they often indicate that the person might be struggling with executive functioning challenges. All the behaviors and clusters I just detailed can be linked to executive functioning challenges. Unfortunately, these challenges are sometimes misunderstood as choices, willful defiance, or even attributed to an inherent personality flaw. In reality, they could be tied to specific skills that need attention and support.

What is Executive Functioning?

To navigate these challenges effectively, the first step is understanding what executive functioning entails. If we were to look it up, the general definition is that executive functioning refers to the set of mental processes occurring in our prefrontal cortex, allowing us to self-regulate and engage in goal-directed behavior.

What People THINK Executive Functioning Is

Many people often link executive functioning with traits like organization, task completion, and being on time. However, it's important to remember that these external symptoms result from internal processes happening in one's head, influencing external behaviors.

Understanding the symptoms and behaviors is critical for recognizing when a student needs intervention in this area. However, it's equally important to understand how these external symptoms align with internal processes so we know how to intervene. When implementing strategies, we want to be aware of the intricate mental processes at play. One common mistake, even with well-intentioned interventions, is overlooking these internal mental processes that are at play when doing simple day-to-day tasks that may seem mundane or common sense.

Many aspects that may be second nature for individuals with strong executive functioning skills often need explicit teaching for those who struggle with these areas. While executive functioning is a hallmark characteristic of ADHD, it also manifests in autism, individuals with a Developmental Language Disorder (DLD) profile, those with dyslexia, or individuals who have experienced a brain injury. Although interventions must be tailored to specific diagnoses, there's a common thread in addressing these diverse challenges. It's about recognizing that executive functioning difficulties cut across various conditions.

When it comes to executive functioning, there's a common perception that someone with good executive functioning is organized. They show up on time, effortlessly keep track of their belongings, and consistently submit assignments on time. While these external behaviors indicate strong executive functioning, they represent only a fraction of the whole picture. Teams working on interventions might have some components in place, often concentrating on these visible aspects but possibly overlooking the broader spectrum of executive functioning challenges and their associated internal processes.

How Executive Functioning is Defined

When clinically defining executive functioning, it encompasses various areas, and the complexity arises because these skills, much like language, have a bidirectional relationship—they impact and influence each other. These mental processes are interrelated, making it challenging to isolate them, which adds a layer of complexity to the intervention process. So, let's look at these mental processes and discuss how they intertwine. Additionally, I'll explore a couple of different organizational approaches to effectively understand how to support children in navigating these challenges.

Attention. The first area is attending, which involves the ability to filter out irrelevant information and recognize when you're off task. It's about sustaining effort towards a task—can you maintain focus on one thing while filtering out the surrounding distractions? Noticing environmental cues is important. For instance, if you're gazing out the window but should be focused on your teacher, can you recognize the cues that signal, "Hey, it's time to redirect your attention over here"? This capacity to attend is foundational and intertwines with various other cognitive processes.

Working Memory. Working memory involves the capacity to take in incoming information and retain it in your mind, whether verbal or non-verbal. The crucial aspect is using this information to complete a task immediately at hand. Consider the example of remembering and typing someone's phone number before we had cell phones. This task relies on working memory—you have to hold the information in your mind and promptly use it. Whether it's verbal or non-verbal information, like setting up something visually and recreating it elsewhere, the ability to hold and use this information in real-time is vital. Difficulties in working memory can impede staying on task and engaging in goal-directed behavior if you are constantly forgetting and unable to retain information.

Strategic Planning. People commonly associate strategic planning and organization with executive functioning, but the key lies in being able to see and feel the goal and its steps. It's not solely about language but envisioning a mental picture of the finished outcome. Consider cleaning a messy room—can you not only see the end goal of a clean room but also picture yourself executing each step? This visualization is important for cognitive strategies, as it allows you to verbalize the language associated with the steps.

If you struggle to picture the end goal vividly, it becomes challenging to estimate how long a task will take or where to find the necessary information. This inability to envision and feel the steps makes it difficult to engage in effective strategic planning. This goes back to noticing environmental cues. Being able to visualize and plan involves understanding the surroundings and the necessary steps to achieve the goal.

Initiation. If you struggle to see and feel the end goal, initiating a task becomes a significant challenge. The ability to envision what a completed task looks like and mentally walk through the steps is critical for starting the task. Initiating a task is closely tied to attending to the right things—it's about focusing on the essential elements that lead to the completion of the goal. This overlap underscores the interconnected nature of these cognitive processes. Initiation is also essential for estimating how long tasks will take. If you can't initiate and get started, accurately gauging the time required for a task becomes difficult. Additionally, transitioning from one task to another relies on effective initiation skills.

Inhibition. Inhibition is closely tied to attention. Let's say you've envisioned yourself cleaning that room, and you're in the midst of the task. How often have you found yourself getting distracted? The ability to inhibit involves restraining yourself from deviating off task, redirecting your focus, and resisting impulsive actions. It's about staying within that goal-directed behavior and having the attention to understand the impact of your actions.

Inhibition isn't only related to goal-directed behavior; it extends to social situations as well. For instance, when listening to someone, can you inhibit the impulse to interrupt with a thought that pops into your head? This skill is vital for social interactions, as interrupting can have consequences, impacting the flow of conversation and potentially affecting others. Inhibition plays a dual role—helping in task-related goal-directed behavior and fostering effective social interactions.

Fluency and Shifting. Fluency and shifting are not just about planning steps and inhibiting behaviors but also about generating ideas fluently. This involves ideational fluency. When faced with a task, your mind generates options and solutions—thinking about how to get it done. For example, when driving somewhere, you might mentally explore possible routes, considering contingencies if there's construction. The ability to generate options for tasks is essential. Ideational fluency is dynamic. In the midst of a task, if something isn't working, you can generate alternative options and ideas. It's about the flexibility to shift and adapt your approach based on the evolving situation.

In the process of generating ideas, we need to assess their quality. This involves not just considering options but also evaluating whether they make sense given the situation. It's about saying, "Here are my options, but this one doesn't align with the current circumstances."

Fluency extends beyond tasks—it plays a role in conversation and social interactions. When conversing, the ability to think of different ways to respond is linked to fluency. It's about considering various ways to act in a given situation. Additionally, it involves considering the context and relevance of the ideas being generated.

Shifting and fluency are intertwined because as you engage in a task, you must have the ability to notice when the plan needs adjusting. We are making constant adjustments to our day-to-day activities. For example, while cleaning your room, you might initially envision the end goal and the steps to achieve it. However, as you progress, you may realize that certain aspects were overlooked, like a part of the closet that needs rearranging. Shifting involves adapting the plan in real-time based on the evolving situation, and fluency allows for generating new ideas and options as needed. You can recognize your progress and your mistakes.

Additionally, time awareness is critical, especially when under time constraints. Whether cleaning a room or getting ready in the morning, knowing how long tasks take is vital for making timely adjustments. For instance, in the morning routine, we gauge how much time each step requires, allowing us to adapt and ensure we leave on time.

Shifting is also important in communication. If we say something to someone and realize they don't understand, we must be able to shift our approach, clarifying and adapting our communication. This situation requires not only fluency in generating alternative ways to convey our message but also the ability to shift and adjust our communication strategy based on the feedback received.

Self-Monitoring and Regulation. Self-monitoring and regulation serve as umbrella terms encompassing all these executive functioning skills. It involves maintaining an awareness of our behavior and understanding its impact. This includes recognizing how our behavior influences the environment around us, progress toward specific goals, and the experiences of others.

Breaking down these executive functioning skills, it becomes evident why someone lacking them might struggle with tasks like turning in assignments, appearing disorganized or off-task, and struggling with time management. But this is why these are the underlying skills that actually impact the output.

What Executive Functioning ACTUALLY Is

What is challenging is how to teach these skills effectively. In my work with clinicians, I've explored various approaches to organize this information, making it more tangible and accessible for individuals. Below is another way that we can look at executive functioning.

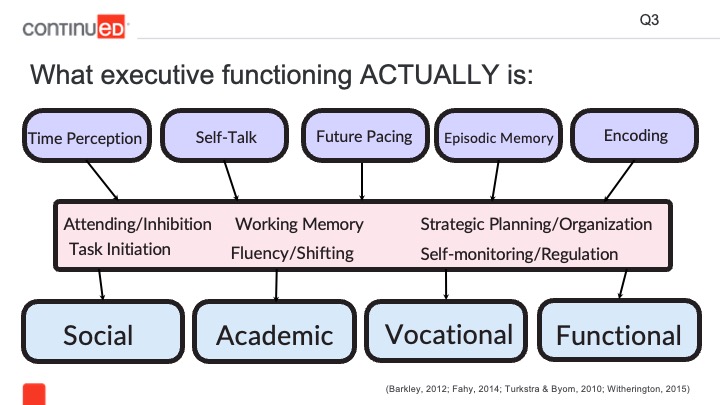

Figure 1.

Looking at Figure 1, the middle section in pink shows all of the areas that were just described. The bottom section in blue shows those areas affected by the skills in the pink section, so we are impacted socially, academically, vocationally, and functionally. These skills are essential in a job setting, and their absence can significantly impact your ability to function effectively. In daily life, managing tasks such as planning meals, organizing, and getting ready on time becomes challenging without these skills. Our goal is to condense these skills into a more manageable set, allowing for targeted intervention. While the items in purple at the top of the chart may not have a direct one-to-one correlation with those in pink, there's substantial overlap. Addressing the five skills at the top of the chart will also address various aspects lower down on the chart, like time perception - can you sense time, and do you understand what time means?

Children with executive dysfunction often struggle with time perception. When you tell them "five minutes," it might not hold much tangible meaning for them. This lack of sense of time makes it challenging for them to self-motivate, especially for tasks that they find undesirable and take a short amount of time. While you might perceive five minutes as manageable, for a child with executive functioning issues, it may seem overwhelming to them if they don't have a sense of time. This impacts their ability to plan and navigate through tasks effectively.

Maintaining focus and keeping up with daily routines, such as getting ready for school, relies heavily on a clear perception of time. Without this sense of time, children with executive dysfunction may find it challenging to stay on task and efficiently complete the necessary steps to prepare for school and leave on time.

Another critical skill is self-talk. This internal dialogue is essential for various aspects of our day, guiding our attention, helping us redirect when off task, enabling strategic planning, and allowing for real-time evaluation of our actions.

This internal dialogue and monologue allow us to regulate and reflect on our actions. For example, when I go downstairs, I might think to myself, "What do I have in my fridge for dinner?" I mentally plan the steps, talking myself through the process. While we all engage in this internal self-talk, it often goes unnoticed because it's so ingrained. Children with executive dysfunction may not naturally have this skill of internal dialogue, impacting their ability to inhibit and plan effectively.

Additionally, the emotional regulation piece is integral to self-reflection and executive functioning. When faced with frustration, the ability to talk to oneself in a manner that promotes calmness, focus, and regulation is part of this critical skill set. Children with executive dysfunction may struggle with this aspect of self-reflection and emotional regulation.

Future pacing is the ability to think through what I should be doing right now to reach a future goal. Whether it's a task five minutes from now or an assignment due next week, it's the capacity to pace into the future and work backward to plan the necessary actions to meet the goal.

Future pacing requires a combination of skills, including engaging in self-talk, utilizing time perception, estimating how long a task takes, and envisioning oneself completing various activities. This process allows individuals to plan effectively, considering the necessary materials, environment setup, and self-advocacy for their needs.

Episodic memory is closely related to these skills, encompassing the ability to reflect on past experiences and apply them to current situations. Children who appear to not learn from their mistakes often struggle with episodic memory. They may lack a vivid mental picture of past experiences, making it challenging for them to plan for the future by drawing on lessons learned from similar situations.

Episodic memory is necessary for planning for the future. It helps with building time perception skills to know how long something will take, how to plan for that, and what should be done right now. Additionally, episodic memory contributes to self-regulation, especially in new situations that are similar to past experiences. By drawing on past knowledge, individuals can navigate new scenarios with less nervousness and greater preparedness.

When episodic memory is lacking, individuals may struggle with task avoidance. The inability to draw on past experiences for success can lead to heightened nervousness in unfamiliar situations.

The encoding process is vital in our mental processes. Whether we are using it for future pacing or recalling past experiences through episodic memory, both instances engage our mental imagery so that we can see ourselves taking specific steps. When it comes to using cognitive strategies and employing self-talk, encoding is essential. This process involves translating those mental images into language, which is an important step for using cognitive tools such as lists, planners, and written notes.

Organizing this framework provides a practical approach to addressing executive functioning skills in the context of day-to-day challenges. While all of these aspects are relevant and important to be aware of with our students, we also need to pair them with internal processes, including the clinical technical terms highlighted in pink in Figure 1, as well as the condensed concepts in purple. My goal with this model is to show how I address executive functioning in a systematic way that builds executive functioning skills, enabling students to apply them in various situations.

Four Common Approaches for EF Challenges

I'd like to share some common challenges we often face in our teams and the typical service delivery models we use. It's essential not to dismiss these approaches, but there's a need to be more intentional in implementing them, especially regarding executive functioning. I'll discuss four commonly used methods and illustrate where the disconnect often occurs. The theme is that these approaches are not necessarily wrong but may be incomplete. We should strive to use them more effectively and supplement them to gain a more comprehensive understanding.

Approach #1: Talk Therapy

The first approach is talk therapy. As an SLP, I acknowledge that we typically don't position ourselves in the mental health space. However, when it comes to executive functioning, issues related to self-regulation often arise. Children exhibiting signs of anxiety, especially in new situations, challenges in making friends, constant task refusal, or extreme emotional reactions, might be referred for talk therapy.

Executive Dysfunction and Anxiety. Continuing on the topic of executive functioning and anxiety, we want to address the interplay between the two. While anxiety can undoubtedly exist independently, there's an ongoing debate about whether executive functioning challenges contribute to anxiety or vice versa. The core issue lies in the chicken-or-egg dilemma. Consider the impact of a weak sense of time perception – for those who effortlessly grasp what 15 minutes means, they have a mental image, perhaps visualizing a quarter of a clock or recalling a task taking that duration. They automatically associate meaning with the number 15. However, for individuals with executive dysfunction, this time frame might appear vague, lacking clear cognitive associations.

So, when communicating with a child who struggles with executive dysfunction, expressions like "It's only 15 minutes" might not resonate as expected. The negotiation process and attempts to convey that the task won't take long – all of these efforts can be challenging. Without a clear ability to envision the future, understand the passage of time, or visualize success, the task remains vague and abstract. In the moment, the child might perceive the demand to engage in an undesired activity as overwhelming, leading to feelings of panic and anxiety.

What looks like anxiety or task avoidance may stem from the overwhelming feeling caused by the inability to envision the future, understand time, or talk oneself through the situation. For individuals with executive dysfunction, the lack of a clear mental image associated with the passage of time makes tasks seem daunting. Without the ability to engage in self-talk that reassures and guides us through challenging moments, the perceived difficulty of the task can contribute to anxiety-like responses or avoidance behaviors. Again, anxiety can certainly exist for other reasons, but this can be a contributing factor.

Additionally, individuals with strong executive functioning skills can rely on mental imagery to navigate difficult tasks. You might still feel nervous, yet you can visualize yourself succeeding. In contrast, weak executive functioning makes the task seem vague and challenging. This is why task avoidance and anxiety may manifest, even in situations that might seem familiar.

Discussing these challenges in talk therapy can be tricky. While it's essential to provide a safe space for children to express themselves, we're asking a child with a developing brain to explain their behavioral and emotional responses. There are many adults who also struggle to explain their executive functioning challenges and lack the necessary language skills to benefit fully from talking about specific situations. They might find it challenging to remember details or explain their actions, simply knowing they didn't enjoy the experience. It's not about removing these approaches but rather ensuring they are done in conjunction with support that addresses the executive function issue.

Approach #2: Behavior Charts

I'd like to discuss another aspect related to talk therapy. Often, children may engage in discussions during therapy sessions but still exhibit signs of anxiety in other settings like the classroom, at home, or during extracurricular activities. Parents might express challenges, mentioning, "It's difficult to get them to sign up for activities; they prefer doing the same things repeatedly." For those in a school setting, teachers may share concerns despite their conversations with therapists. Even after discussing classroom expectations, some behaviors persist. To reinforce therapy efforts, people often resort to using behavior charts. This is common when dealing with children facing challenges like not following directions, difficulties with transitions, not completing multi-step tasks without prompts, refusals, off-task behavior, or struggling with emotional regulation and extreme emotional reactions.

The next line of thinking is, "We need some kind of strategy in the classroom to provide structure." And that thought is in the right ballpark. However, in terms of behavior management, especially when dealing with behaviors like task refusal or staying on track with multi-step tasks, what's visible externally is just the surface. Internally, there's a mental aspect impacting the ability to show motivation outwardly, and it might be mistakenly perceived as laziness or defiance. When considering the internal processes needed for self-motivation, these are the mental steps that must happen.

We need to be able to envision that end goal and also visualize the reward that comes with achieving that goal. Rewarding ourselves is a common practice, and we can mentally anticipate how fulfilling and satisfying the experience will be in the end. This is how we navigate through tasks during the day that we may not particularly want to do. Moreover, in the moment when we don't feel like doing something, we must consider the choices and weigh the options of one activity versus another. It involves visualizing the necessary steps, estimating the time required, contemplating potential obstacles, and generating various options for completing the task at hand.

Then, we must encode those steps into language. To engage in self-talk about the steps, we need to have a mental picture and pair it with language. In situations where a visual aid or a list is necessary, like when shopping and needing to remember items, we might need to write some of it down. Knowing when to employ these strategies is crucial. Following that, we have to initiate the task. While in the process, we need to constantly evaluate our progress, keep an eye on the time, consider the anticipated outcome, and weigh our choices, especially when faced with tasks we find challenging or unappealing, experiencing boredom or frustration.

We need to keep reminding ourselves of that outcome, which requires our ability to future pace. Additionally, we must use our episodic memory to reflect on past experiences, as it helps us consider potential consequences. When we simply implement a behavior chart or system, especially if it involves sticker charts, we aren't effectively activating or teaching these internal skills necessary for self-motivation. Stickers or abstract rewards may not be immediate or tangible enough, as the true reward often lies in something else the individual is working towards.

If a child struggles with time perception, the actual reward might be too distant in the future, making it insufficient for self-motivation. Moreover, self-reflection and self-talk are essential, and a sticker chart doesn't provide the tools to help children develop time perception or track their progress effectively. It lacks the experience they need to internalize and store the experience in their episodic memory. Therefore, the first step is to realize what we are actually asking children to do.

I want to emphasize that relying solely on rewards and punishments is not about eliminating consequences for children. We want to let consequences occur or establish structures with immediate consequences as part of effective intervention. However, we need to go beyond just focusing on consequences. Teaching the necessary skills is essential because you can't incentivize a child to use skills they haven't acquired. Skills like future thinking and visualizing processes are what enable us to initiate and persist through challenging tasks. It's essential to view motivation and persistence as skills, not just personality traits. Therefore, the goal is not to eliminate consequences but to use them in conjunction with skill-building, not in isolation. Often, people think that behavior problems are all about rewards when it's really much more than that.

Approach #3: Checklists/Planners

Checklists and planners, much like the behavior chart problem, are frequently used in classrooms to teach students organizational strategies. This approach is often taken when children exhibit challenges in following directions, completing multi-step tasks, missing assignments, are reported to have poor time management, or frequently lose personal belongings.

Using checklists and planners can be helpful when supporting children with their homework. The idea of creating a checklist or filling out an assignment notebook seems reasonable as a way to provide structure. However, a potential challenge arises with the retrieval aspect of this strategy. Executive functioning involves the ability to pay attention to relevant information, including environmental cues. These cues guide individuals on which tools to use for a particular task.

For instance, imagine a child in elementary school entering the classroom where peers are already taking out their assignments. The environmental cue here is an indication for the child to retrieve their materials, planner, or any necessary tools from their bag. However, if the child lacks the skills to use these cues, they might struggle with knowing which tool to pull out at the right time, resulting in difficulties with retrieval.

Lists are frequently recommended as an executive functioning strategy, but in reality, they are not. Using lists can be helpful in specific contexts, but we must recognize their limitations. Lists, while not inherently bad, are somewhat superficial when it comes to addressing executive functioning challenges.

To elaborate, consider what happens internally when you use a list. Like the behavior chart, you need to envision your end goal, visualize the steps involved, consider the necessary materials, estimate the time required, and think about potential obstacles and relevant options. You need to know what goes on the list and have the language to write those items down. We engage in initiating the steps, evaluating the ongoing process, shifting and redirecting as needed, and reminding ourselves to reference the list. Additionally, episodic memory, self-talk, and visualization play important roles.

However, the common practice with children is often limited to copying from a board or having them write down a pre-provided list. This approach may miss the opportunity to develop and reinforce the internal executive functioning skills essential for effective task management and organization. We've essentially overlooked many of the internal processes necessary to understand how to use a list. By bypassing these internal steps, we end up doing the executive functioning for them. This approach denies them the opportunities to develop the skills needed to effectively use whatever strategy is at play. It's crucial to perceive these tools as tools, not executive functioning strategies. They serve as tools that come into play when we're already using executive functioning skills and engaging in internal planning. These tools, in themselves, do not teach executive functioning skills. While they may be appropriate to use in specific situations, it's essential to recognize that the tools are not the strategy. They are resources we may use while actively teaching the skills.

Approach #4: Social Skills Groups

Lastly, social skills groups. As mentioned earlier, many of these skills significantly impact our relationships, affecting our ability to engage with others in unpredictable situations that demand the use of working memory, as well as the ability to shift, redirect, and reflect. When children encounter challenges in their social interactions, a common intervention is using social skills groups.

Factors frequently leading to referrals for social skills groups may include difficulties in maintaining conversations, lack of initiation in conversations, interruptions, excessive focus on personal interests, and engaging in one-sided conversations. So, these individuals engage in conversations, sharing information extensively without necessarily observing the reactions of the other person. They may tend to isolate themselves, avoiding social scenarios, particularly when they perceive a high degree of structure or when something feels new and unfamiliar. Additionally, they may face challenges in reading the room. The struggle lies in their ability to approach a situation, join a conversation, and use environmental cues for strategic planning and successful engagement.

Academic Versus Social Skills

It's important to distinguish between academic skills and social skills because groups and therapy lessons are often structured in more of an academic format. In many cases, the skills required to participate in an academic therapy-type setting, especially if it's adult-led with scenarios, questions, and answers, involve tasks like asking and answering questions, describing narratives, retelling stories, or explaining what to do in a given situation. While these skills are relevant and necessary for academic and social contexts, they don't give students everything they need. What's essential for students to navigate unstructured situations is the skill of situational awareness. This involves reading the room, knowing where to find information, considering real-time responses and thoughts of others, and being able to inhibit, initiate, and respond.

This skill set is very different from sitting with a therapist in a social skills group, where you may have to explain how you would respond in a hypothetical situation. Many of us have experienced planning a reaction in our heads, envisioning ourselves in a situation, but when it unfolds, it doesn't go as planned. Adjustments, nervousness, or unexpected events may occur, requiring practice in reading specific cues and context to be successful. Both skill sets are important and should complement each other. However, addressing social skills solely in an academic context may only give students practice within that framework. Often, the focus is on rules and politeness, which, in some cases, can further isolate them if they appear rote, awkward, or overly formal, making them less relatable to their peers. They don't know when to pull those rules out at the right time, and that's just not how kids interact with each other.

Planning for Therapy vs. Planning for Service Delivery

When planning therapy, we need to consider time perception, self-talk, future pacing, episodic memory, and encoding, understanding how these internal mental processes impact children across various settings. To provide a tangible strategy for building these skills, I'll cover the details in Part 2 (Course 10791), but here's a quick overview before concluding. Shifting your mindset from planning for therapy to planning for service delivery is a critical step. Today, I discussed numerous strategies applicable in various settings, both in therapy and in the classroom.

To successfully address executive functioning, we must consider therapy-specific aspects like protocols, lesson plans, and materials. But that is just the first step. While therapy is essential, it alone cannot effectively address executive functioning challenges for the reasons discussed earlier. We need to look at the big picture, incorporating training, coaching, consulting, and sharing our knowledge with others. Direct intervention remains crucial, but expanding our approach allows us to train others and impact students in real-life situations. Especially in social contexts, students benefit from practicing with eyes and ears in genuine situations with someone reflecting back with them. They need that practice. This is where we need to be creative in planning our interventions and look for opportunities to do interventions in the community or classroom outside of the therapy room.

Additional Resources

- Executive Functioning Implementation Guide: drkarendudekbrannan.com/efschools

- Executive Functioning Training: drkarendudekbrannan.com/efleadership

- Find these “De Facto Leaders” Podcast Episodes on podcast directories or defactoleaders.com

- EP 101: How school therapists can lead schools in providing district-wide executive functioning supports

- EP 107: How to make social skills intervention evidence-based and neurodiversity-affirming

- EP 110: Empathy, masking, and situational awareness

- EP 122: Executive functioning for college students: Beyond checklists and planners (with Jill Fahy)

- EP 125: Time perception, anxiety, and future pacing

References

Please see additional handout.

Citation

Dudek-Brannan, K. (2024). Executive functioning for school-age children: it's more than being organized, part 1. SpeechPathology.com. Article 20641. Available at www.speechpathology.com