Introduction and Overview

The topic in this course is near and dear to my heart. Dementia is my area of specialty but I spent the first 10 years of my career working in research. Two of the intervention strategies that we looked at during my time in the Research Institute were spaced retrieval (SR) and Montessori. I was able to not only research these interventions, but to use them regularly in my current practice and in teaching my graduate students in our clinic at Kent State University. So I am happy to share all of this information with you.

Know that this is an overview, so we are going to hit the highlights of both techniques in this course and then I can always dig deeper into your questions via email after this course as well. I recommend that you take a look at some of the resources and references that I have listed at the end of the course for additional ways to learn more about spaced retrieval and Montessori.

As we get into the details about each of these techniques, how many of you are familiar with or use the spaced retrieval technique? It looks like a few of you are using it or at least have some familiarity with it. Hopefully, I will be able to give you a little more information not just about what the technique of spaced retrieval is, but also some ways to use it, and some creative ways to establish prompts and so on. The next question is how many of you are currently using Montessori techniques with the dementia population? It looks like there are many of you who are not quite familiar with it; but that is why you are taking this course, right? I think that it will be exciting for you to learn a different twist on some ways to intervene with persons with dementia.

I want to disclose that I am a co-author of a book called “Here's How to Treat Dementia,” and some of these methods I will be discussing are mentioned in that book, and I do receive financial compensation for that. I would also like to acknowledge that I would not be here without the work of many other people, and I want to take a second to acknowledge those who have been involved in the research of both of these intervention techniques, as well as in the implementation and use of them, and giving feedback about their use and so forth. I worked for a number of years in Menorah Park Center for Senior Living, in Beachwood, Ohio where the Myers Research Institute was housed. They do wonderful things there, and a lot of the research and information that I am sharing in this course was done on their campus and with their support. The State of New York Department on Aging really provided some great insight as we did some grant studies with them looking at how to implement spaced retrieval across a system. We wanted to see what things get in the way when you are trying to train staff and trying to get everybody on board using a new technique, and what things really help support programs. We did that with spaced retrieval in three long-term care facilities in the State of New York, and had some great support from their Department on Aging as well as all of the facilities that we worked in. We learned some good lessons, and I will be sharing some of those with you today as well.

Hearthstone Alzheimer's Care, in Massachusetts, is a great proponent of the Montessori technique. I encourage you to look into what they are doing. They continue to conduct research related to Montessori and many other things as well. Northern Speech Services is a great support in terms of allowing us to provide online education related to some of these interventions. The National Institute on Aging and the Retirement Research Foundation are great resources as well. And I was remiss in not putting up the National Alzheimer's Association. They actually funded a grant that allowed us to look at using Montessori methods to improve family visits to nursing home residents. That study led us in a lot of great directions and helped us understand this method more, and how to encourage non-professionals to use it.

Dementia Review

I want to start by doing a brief review of dementia. I am sure all of you are intimately aware of what dementia is, what its characteristics are, symptomatology, and so on, but I always think it is good to briefly touch on some of those points to provide a nice foundation as we get into discussing how and why different intervention techniques can work.

This information was provided through the Alzheimer's Association. We need to keep in mind that dementia is not a specific disease; it is a descriptive term for a collection of symptoms that can be caused by a number of disorders that affect the brain. Alzheimer's disease could be one of those disorders affecting the brain, and that actually accounts for about 60 to 80% of dementia cases. Vascular dementia, which occurs after stroke, is the second most common type of dementia. I get a lot of questions about the difference between dementia and Alzheimer's disease, particularly from my home health clients and their families, and our clients who come for outpatient therapy at our university clinic. There is a lot of confusion out there. Does he have dementia? Does he have Alzheimer's? What are the differences? So it is important for us as practitioners to really understand those differences and be able to relay correct information.

I typically talk about it as dementia being the descriptive term. It can include things like language disturbances, problematic behaviors, difficulties with activities of daily living, and personality changes. When these kinds of symptoms are occurring, I tell families that these tell us there is something bigger in the system that is going on. You may see the person not being able to quite remember the name of something, or chronically not remembering certain people's names or what they did earlier in the day, asking the same question over and over again, starting to show some difficulty with basic sequences of how to get themselves dressed, do their grooming, or other typical things around the house. Perhaps they always made their coffee in the morning and now they are struggling with the steps that go into that. There may be changes in personality; perhaps they were once quite active and engaged in things and now they are pulling away, or tending to be a little bit more aggressive. These things tell us that something bigger is going on. It is almost like when you have a fever. That tells you that something else in your system is not quite right. It might be the flu, it could be something else, but the fever is a symptom of another problem. When we see these changes in language or behavior occur, we know we need to look a little deeper. It is important, then, for the family or the person to talk to their physicians and get a full work-up to understand what might be happening.

Memory and Dementia

Memory is extremely complex, but it is part of what we deal with as speech-language pathologists in terms of our intervention work with persons with dementia. The primary characteristic, the hallmark thing that we think about when we talk about dementia or Alzheimer's disease, is difficulty with memory. So it is important that we have at least a cursory understanding of how it works. I encourage you, if you want a little more help understanding memory, check out a course that my co-author Jenny Loehr and I did back in May: “Alzheimer's 101.” We get into a little bit more detail about memory there. But for the purposes of this course, let's talk about what memory is.

We know that memory is dependent on organizing incoming information. We have to attend to something and then we have to have highly developed encoding skills in order to work with that information, either immediately or to store it for long-term use. We know that memory is critical to our ability to acquire language, to develop higher-level thinking, and to effectively make decisions. In its most basic form, we might think that memory is all about remembering that person's name or what we did a few minutes ago; but it also is key in terms of being able to learn new things in order to make decisions. We have to remember what the consequences might be so that we can make a decision based on what may have happened to us previously when we did something. Memory is critical for a number of different functions, so that is why it is important for us to know how to effectively work with it. We need to improve, to the degree that we can, patients’ memory function so they can continue to be as active as possible, make choices about their lives, and learn new things, in order to be productive members of society.

Memory Stages

When we think about stages of memory, we first think about attention, as we just mentioned. You have to attend to something, then encode it, store it, and retrieve it. All of these things are very interactive processes, so they are all going on at the same time. The ability of one process affects the quality of another. In order to encode something well, we have to pay attention to it. Today, if you want to remember what spaced retrieval is, you are going to have to listen and pay attention to me for as long as you can, and then you are going to have to think about ways that you can make it meaningful for yourself so you can remember it. You might do something like create an acronym for it. What does spaced retrieval stand for? Or you might visualize someone trying to remember something up in space. We all have different strategies that we use to try to process and make information meaningful, and then encode it.

Then we have to work on storing it and retrieving it. The more we do those things in terms of storing it well, practicing using the information, and using it frequently (the retrieval piece), the better we are going to get at remembering it. All of those pieces are interactive and dependent on one another, so if we can make everything effective at those different stages we should be in good shape. If one stage is a little weaker than another, then we have to think about how we can beef up those weaker areas, and hopefully then see improvement. A deficit in one stage can lead to deficits in another stage; we already covered that.

Memory Definitions

When we think about memory definitions we can talk about working memory, short-term memory, long-term memory, and so on. Again, these are things that I think we all really know well, but our families or caregivers or nursing assistants in facilities or in home care might not quite understand some of this. It is important for us to have good working definitions of these things so we can educate other people. It helps them understand what we are doing and what we are consequently going to be asking them to do as part of carryover and generalization of the things we do in therapy.

With working memory and short-term memory, we are talking about the ability to use information as it is being processed. An example is remembering a phone number. Someone gives it to you, you quickly pay attention to it, and you use it immediately. Typically that information does not get stored into long-term memory. You use it and it is gone. We tend to see this type of memory being affected first with Alzheimer's and other dementias.

Long-term memory relates to information from short-term memory that is retained permanently. The way that happens is through that good encoding and use. It is information that you are using on a regular basis. Think about when you were in grad school studying for an exam and you kept reading your notes over and over again and thinking about ways to make that information meaningful. That was helping to transfer that information that was previously in short-term memory without a lot of meaning to long-term memory. You found ways, with the repetition and so forth, to memorize it and get that information into long-term memory. You might have also done exercises like sitting around with your study group and talking about things, or writing everything down. With that continuous rehearsal and then retrieval, the information becomes something that is stored more permanently.

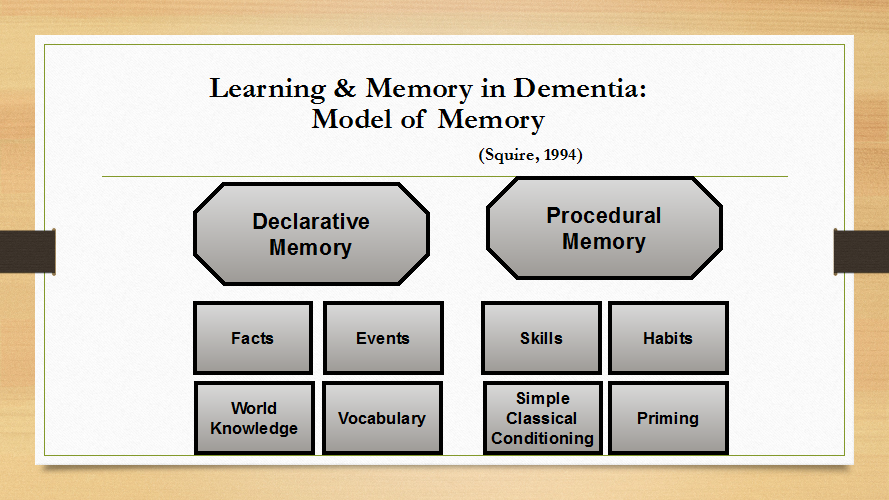

Subtypes of long-term memory include declarative and procedural memory. Those are important as we discuss intervention methods, because procedural memory in particular is less impaired with the progression of something like dementia. We want to capitalize on strengths, so procedural memory is a part of long-term memory that is important for us to understand and know that we can use.

Both storage and retrieval aspects of long-term memory can be affected by dementia. Unfortunately we are not going to be able to get around everything. Dementia and Alzheimer's disease are going to be progressive issues. We cannot necessarily stop that progression, but we can improve on the person's ability to use information and capitalize on strengths that are present in order to make them as functional as possible for as long as possible, and really improve their ability to engage with life.

Model of Memory

Figure 1 shows a model of memory that I use frequently in educating families and patients.

Figure 1.

This is a model of long-term memory, and again, there are two parts of long-term memory. So we know that short-term memory/working memory can often be impaired earlier in the progression of dementia, and that long-term memory can stick around a little longer. This model is great in terms of being able to clearly understand what is spared and what is a little bit more impaired. This is the work of Dr. Larry Squire. This is a 1994 citation and it has continued to be an accepted understanding of how long-term memory works; it is “the gold standard” in terms of understanding memory. I have included this reference at the end of your PowerPoint so feel free to look into his work to understand memory a little bit further.

Declarative memory. For our purposes, this model is saying that long-term memory can be divided into declarative memory and procedural memory. Declarative memory holds things like facts and events; things like who we are, what we did the previous day, where we live, and that kind of thing. It also holds information such as our knowledge of the world; e.g., understanding that Paris is the capital of France. World knowledge is something that we have learned in life, but that is not necessarily tied to who we are or our own autobiographical memory. The final thing that we see stored in declarative memory is vocabulary -- the language piece. This includes being able to remember what something is called, and being able to understand what someone else is telling you.