Introduction and Overview

Definitions

Since this is a “back to basics” course, we will start with the basics. A motor speech disorder is any disorder of speech that results from a neurological impairment. That neurological impairment could affect motor programming or motor execution. In this course, we are going to talk about dysarthria, which is the execution side. In someone with dysarthria, the programming is present, but the way that the program is executed is impaired as a result of some kind of weakness, paralysis, incoordination, or inadvertent muscle movements of the speech mechanism.

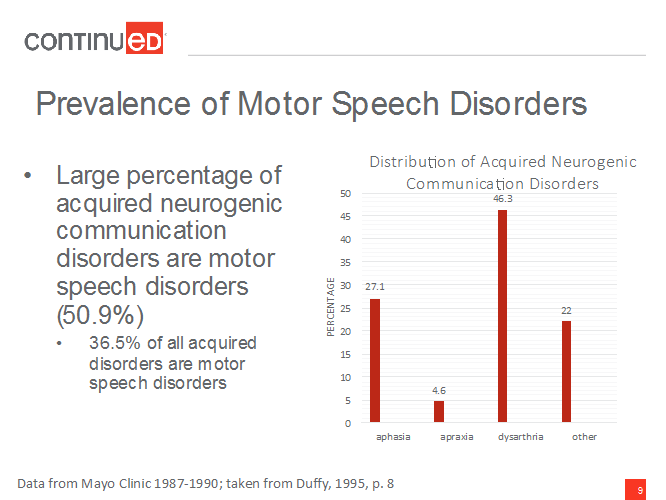

Prevalence of Motor Speech Disorders

Motor speech disorders are quite prevalent. Based on data from the Mayo Clinic (Figure 1), a large percentage (50.9%) of acquired neurogenic communication disorders are motor speech disorders. You can see that dysarthria actually outpaces aphasia as an acquired neurogenic communication disorder. If you are working in a medical setting, you are probably seeing these kinds of patients.

Figure 1. Prevalence of motor speech disorders.

Team Approach

It is no surprise that everything in speech pathology is a team approach. We want to work with other professionals in our practice. This is obviously not an exhaustive list, but we will definitely work with occupational therapy (OT), physical therapy (PT), respiratory therapy, and a whole host of different doctors, including primary care physicians, otolaryngologists, pulmonologists, and neurologists. If you are working with a child who has dysarthria, you may also have a psychologist from the school, the teacher, and/or special education staff on the team. Of course, our most important team members are the client and family. We always have to consider them when we are making our assessment and treatment plans.

Darley, Aronson and Brown Dysarthria Classification System

Overview

I will start with this basic background - the classical look at motor speech disorders - and discuss how it dovetails with different neurologic diagnoses. From there, I will talk about how to assess these disorders.

Darley, Aronson, and Brown worked at the Mayo Clinic, and in 1969, they developed a configuration system for dysarthria. They started with six types.

Flaccid. One type of dysarthria is the flaccid type. When you hear the word flaccid, it makes sense that the physiology underlying this type of dysarthria is weakness. What happens in this type of dysarthria is that there is a problem with nerves in the final common pathway - also called lower motor neurons (LMN), or cranial nerves and spinal nerves - as those nerves are heading out to their final targets. That causes weakness or sometimes paralysis in the muscles, resulting in flaccid dysarthria.

Spastic. The physiology with the spastic type is probably obvious. At a neural level, there is bilateral damage somewhere in the cortex, in the upper motor neurons (UMN). This could be in the pyramidal system or the extrapyramidal systems. Either way, bilateral damage can cause spastic dysarthria.

Ataxic. Ataxic dysarthria is due to a problem in the cerebellum. With this type, the key word is incoordination. Someone who has ataxic dysarthria or ataxia in the limbs will seem very uncoordinated in their movements. They may have problems with stepping or reaching, tending to overshoot or undershoot their targets.

Hypokinetic/hyperkinetic. For hypokinetic dysarthria, the neural basis is related to a problem in the basal ganglia. You will notice that hypo- and hyperkinetic dysarthria look similar not only in their spellings, but also because they both have the neural basis in the basal ganglia; however, they are opposites. Hypokinetic means that we have reduced range of movement, rigidity, and stiffness in the muscles. Hyperkinetic is the opposite; we see extra involuntary movements that are called dyskinesias.

Mixed. All good classification systems have a “mixed” category. This could be a mix of any of those other types. This can also be called “undetermined”; sometimes you see a patient with dysarthria and you do not know what you are hearing, and that is okay.

These categories are how we think about dysarthria in a classic sense, and are a good backbone for classification moving forward.

Unilateral UMN. Another one that has been added since the original six types were designated is the unilateral upper motor neuron type. I am not going to spend time on this type in this course. This tends to be milder form of dysarthria. The neural basis is unilateral cortical damage. So this is different from spastic in that there is bilateral damage in the spastic type; in the unilateral upper motor neuron type, the damage is just on one side. With this type, we will see weakness and maybe a little bit of incoordination. In general, it is a very mild dysarthria that often will resolve in a short period of time.

Childhood vs. Adult Dysarthria

Here is one caveat about these categories. When children have dysarthria, these categories tend to be less useful. Sometimes the terms “spastic cerebral palsy” or “hyperkinetic dysarthria associated with cerebral palsy” will be used for children. For dysarthria of childhood, the descriptors do not fit as well. With children, we always have to remember that development is occurring on top of everything; therefore, the interaction between development and the dysarthria can be less predictable than what might be seen with an acquired dysarthria in adulthood.

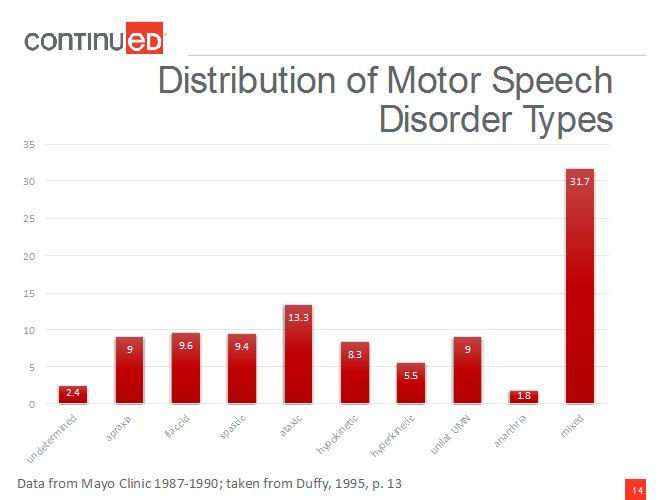

Distribution of Motor Speech Disorder Types

Here is the distribution of all of the dysarthria types (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Distribution of motor speech disorder types.

The data shows that the most commonly occurring type is mixed. This is why I say that knowing exactly which one of these a patient has is not the most important part of assessment. The types simply serve as a framework from which to start an assessment and structure your thought processes, related to motor speech disorders.

Why Consider Dysarthria Type?

However, classifying dysarthria type is important for a couple of reasons. One is that it commonly happens that speech symptoms are the first sign of a neurologic disease. As a speech pathologist, by knowing what type of dysarthria we are hearing, we can help the medical team determine what type of disorder or diagnosis they are dealing with, and what the care may entail. For example, knowing that we are hearing spastic dysarthria lets the medical team know that we are likely dealing with some kind of bilateral damage in the cortex, which can, in some cases, help direct where the medical assessments are targeted.

Knowing the type of dysarthria can also influence treatment decisions. If we see that phonatory changes are occurring as a result of weakness, as opposed to resulting from incoordination, we would think about strengthening. In contrast, doing strengthening exercises is not going to help with incoordination.

Again, these dysarthria categories are not an overall perfect fit. They definitely do not predict the impact of dysarthria on the patient's life very well, and that is something we always want to consider.

As a framework, I want to discuss the types of disorders that are seen with the different types of dysarthria.

Flaccid

The flaccid type is the most variable. The symptoms vary quite widely depending on what cranial nerves are involved. If cranial nerve (CN) XII that innervates the tongue is impacted, articulatory functions, and particularly lingual consonants, are affected. If there is damage to the recurrent laryngeal nerve that innervates most of the intrinsic muscles at the larynx, then there are voice problems. Therefore, always think very broadly about flaccid dysarthria and weakness.

Oral motor exam. With this type, there will be problems with actual weakness in the oral motor exam. As a quick review, the oral motor exam looks at the structure and function of the mouth and face. The lips, tongue, palate, and the voice are examined to see if there is weakness, asymmetry, or reduced range of motion in the structure and function of the oral musculature.

With flaccid dysarthria, there will be weakness and often reduced range of motion, for those articulators that are affected. If the jaw innervation is affected, when the person opens his jaw, it will deviate to the weak side. Similarly, if the tongue is affected, when he protrudes his tongue there will be deviation to the weak side. This is because that strong side is overtaking the weak side and pushing on it such that it deviates to the weak side. We will often see drooling with these patients, particularly if they have tongue weakness.

Articulation. I am going to go over a few symptoms here related to how these patients sound, from an articulation standpoint. With every dysarthria type, there is often imprecise articulation of some kind because that is the defining characteristic of dysarthria. But, if the flaccid dysarthria is really only impacting the velopharyngeal system and/or the voice system, then we will not see imprecise articulation. If the tongue, the lips, and the jaw are all intact, there may not be imprecise articulation.

Resonance. There might be issues with resonance. If the person has problems with the velopharyngeal port, they may have hypernasality and/or nasal emission. Here is a quick note about distinguishing hypernasality from nasal emission. Hypernasality is a true resonance issue; it sounds more “nasally.” Nasal emission is not a resonance issue, even though we describe it that way sometimes; it is turbulent, audible airflow through the nose. It sounds a little “buzzy,” almost like a voiced fricative, but it does not come from the oral cavity. So, while both hypernasality and nasal emission can result from reduced velopharyngeal closure, they are different concepts.

Prosody. People with flaccid dysarthria often use short phases. If they have respiratory or laryngeal involvement, they cannot support longer phrases; they need to shorten those phrases because they run out of breath. They may also have monopitch or monoloudness as a result of laryngeal difficulties as well.

Phonation. Often, people who have phonatory or laryngeal involvement will have a breathy voice. We might hear audible inspiration, where the vocal folds are not fully opening for inspiration. When that happens, turbulent airflow might go through the vocal folds during inspiration causing a raspy type of sound as the person breathes in.

Associated neurological diagnoses. There are many diagnoses that go along with flaccid dysarthria:

- Brainstem stroke is a very common cause of flaccid dysarthria. The brainstem stroke could be unilateral or bilateral. The more severe it is, the more likely it can lead to locked-in syndrome, where someone cannot communicate, and often cannot move her body or at least much of her body.

- Guillain-Barré syndrome is a syndrome that has a relatively quick onset of weakness that can lead to complete paralysis. Typically, there is improvement, with many cases reported as completely recovering over time.

- Myasthenia gravis is a disorder that has weakness with muscle use. This is actually a disorder of the neuromuscular junction, so it is very much in that periphery where the nerve meets the muscle. A person using those muscles experiences weakness over time, but if she rests, the muscle will become stronger again. Sometimes it will recover completely to normal strength, but more often, the person is left with weakness and never completely feels like she used to. Again, rest is important to gain improvement.

- Muscular dystrophy is another common cause of flaccid dysarthria. There are a couple of types: Duchenne muscular dystrophy is a childhood type, and myotonic is a very common adult type.

Spastic

Oral motor exam. Spastic dysarthria has bilateral damage in the cortex in the upper motor neurons. Often, pathological oral reflexes are present. Patients may have a suck reflex, snout reflex or jaw jerk reflexes, all of which can be tested as part of the oral motor exam. Drooling may also occur with these patients.

We may see lability of affect; this is a distinguishing feature of spastic dysarthria. It does not happen in all people with spastic dysarthria, but it can happen. The person may fluctuate between laughing and crying for no reason. They may report that their facial expression does not really match their inner feelings. For example, a person may feel very happy and be crying. I know that happens to some of us, but it is not lability of affect. For these patients, it is more consistent and happens more regularly.

Alternating motion rates (AMR) - for example “pa-pa-pa-pa” - are often slow and reduced in range of motion, but they tend to be very rhythmic. We see impaired patterns of movement, but do not typically see weakness in muscles. It is not that, for example, the jaw is weak, like it is with flaccid dysarthria.

Articulation. With spastic dysarthria, individuals often have imprecise articulation. The one thing that is unique is that they sometimes have distorted vowels. We do not often see vowels impacted in the dysarthria types, but in some we do, and spastic dysarthria is one of them.

Resonance. Occasionally individuals with spastic dysarthria will have hypernasality. It is not just in flaccid dysarthria that hypernasality occurs. It tends to be fairly common if the velopharyngeal port neurons are affected. In spastic dysarthria, hypernasality can occur if the velum becomes spastic and causes problems with closure. However, that may not always happen.

Prosody. Some features are similar to those seen with flaccid dysarthria. Individuals will use short phrases, monopitch and monoloudness. In flaccid dysarthria, these characteristics are due to weakness. In spastic dysarthria, the muscles are tighter and do not have the same range of motion, so it is harder for people to make prosodic changes in their speech. Sometimes we hear excess and equal stress, meaning that the stress on every word tends to be the same, such that we do not hear that nice rhythmic, strong/weak pattern that we have in English. We might instead hear reduced stress where the level of stress placed on words/syllables is just lower overall. Another very common feature in spastic dysarthria is a slow speaking rate.

Phonation. With spastic dysarthria, individuals often have a low pitch. Unlike flaccid dysarthria where we hear a breathy voice, these individuals have a strained-strangled or a harsh type of voice. The strained-strangled voice – but not so much the harsh voice - is very indicative of spastic dysarthria. Sometimes there will even be pitch breaks because there is a lot of tightness in the larynx.

Associated neurological diagnoses. There are a number of disorders that cause spastic dysarthria. Spastic dysarthria is often one of the major components of mixed dysarthria. We will talk about that when we review amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), or Lou Gehrig's disease. That is a mixed dysarthria that is flaccid-spastic, and often, spasticity is the early component with flaccid characteristics presenting later on; sometimes though, it starts as a mixed dysarthria.

In traumatic brain injury (TBI) and in multiple sclerosis (MS), there is the potential to have any single type of dysarthria or any mixed dysarthria, but often for those diagnoses, spasticity will be a component of that mixed dysarthria.

The other thing to know about listening to these types is that it takes time. No one is good at this on day one. You have to take time and hear a lot of them. Perhaps you could work with someone who has been doing this a while and has a good ear for dysarthria types. They can say, “Do you hear that? Do you hear those articulatory breakdowns? Do you hear that harsh voice or that strained-strangled voice?” They can really help you.