Introduction and Overview

Before I begin, I would like to conduct some polls. The first question is, “When seeing patients, how many of you engage them in conversation?” This could be asking patients about how their day was, whether they enjoy the food at the hospital, the type of show they watched over the weekend, or whether they have any pets. Based on the poll, I see that the majority of you talk to your patients; very good. The second question is, “What type of topics do you usually discuss with your patients?” Do you ask them about their family members -- especially grandchildren? Do you talk about their previous work experience, or things that they enjoy doing, such as interests or hobbies? Do you ask if they watched anything on the news, and discuss these current events? It looks like most of you talk to your patients about interests and hobbies.

Patient-Centered Care

Preferences in Aphasia Rehabilitation

I would like to begin this course by discussing the importance of patient-centered care. Patient-centered care is at the heart of discourse intervention in aphasia. Imagine yourself coming across a newly established restaurant in your neighborhood, and upon entering, you realize that only the chef is allowed to choose a meal for you, based on his own impression. Some customers might be mandated to eat a high-carbohydrate diet, or might be placed on a low-sodium diet without considering the patient's preferences. If the restaurant owner prolonged this policy, most customers would probably complain about it and the restaurant would eventually close. In like manner, it is very important for us to tailor our treatment to what our patients prefer.

What exactly do persons with aphasia (PWA) want? In 2011, Worrall and colleagues examined the goals of patients with aphasia, and they found that essential goals included: increasing independence and respect; obtaining more information about aphasia, stroke, and services; communicating opinions; and engaging in social, leisure, and work activities. So, the majority of the goals highlighted the importance of activities of daily living to persons with aphasia. In fact, a recent study by the Cleveland Clinic has shown that in addition to the physical limitations of patients who have had a stroke, quality of life in stroke survivors was affected by feelings of isolation, or the lack of participation in social activities.

Life Participation Approach

To address the need for patient-centered care, several approaches were developed. Simmons-Mackie and colleagues (2008) introduced the Life Participation Approach, whereby clinicians were encouraged to facilitate successful participation in persons with aphasia. This meant providing communicative support systems in various communication environments, or promoting advocacy in social actions. If we were to look at blogs of patients with aphasia, we would see that social action is very much promoted via testimonies of surviving a stroke.

The life participation approach also emphasizes the importance of having intensive and individualized aphasia therapy. This means providing them with activities that will give make a meaningful impact on communication in real life. This goes well beyond the physical limitations of the stroke, and closely looks at the person's emotional well-being and their life activities and how satisfying these are, or looking at social connections - who they deal with - and how satisfying these are.

Living with Aphasia: A Framework for Outcome Measurement (A-FROM)

Another model that centered on patient-centered approaches was developed by Kagan and Simmons-Mackie (2008). It is called Living with Aphasia: A Framework for Outcome Measurement. This is a reinterpretation of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) framework, but it is tailored more specifically to the needs of persons with aphasia. With this model, they consider the impact of aphasia on life areas that are important to persons with aphasia, as well as to their family members. The theme of living with aphasia becomes central to various domains. One domain is personal identity, feelings and attitudes, and how these affect a person's life. Another domain is language and related impairments. We also look at communication and language environment, as well as participation in life situations.

To digress a bit, this reminds me of a quote from a woman who had aphasia. She said, "People think I have a thick accent. They often ask me what my country of origin is. I want to tell them that I come from ‘a land called, Aphasia.’” That really is how it is. We want to see how patients are doing in various life contexts, while trying to deal with their aphasia as well.

The Life Participation Approach offers persons with aphasia outcome measures that are person-centered. In other words, the person with aphasia often determines and chooses the relevant outcomes, and judges what is most meaningful in his or her life.

Functional Communication in Aphasia

Functional communication is very essential; it is part of patient-centered care. Patient-centered approaches really put the patient at the core of aphasia rehab. In many respects, patient-centered care is very closely tied to establishing functional communication tasks. This means setting up contexts that are natural and personally meaningful to the person with aphasia.

Why is it important to establish functional communication in aphasia? What they are finding is that there is very limited transfer to untrained items, especially given the short period of time that we see our patients. Also, Hinckley and colleagues (2001) discovered that there are significant gains in communicative competence when contexts are practiced in therapy. Again, given the limited amount of time we see patients, it is very important to go back to patient-centered care.

Discourse

This brings us to the topic of discourse. What exactly is discourse? Discourse is language that is beyond the boundaries of isolated sentences. It is the manner through which sentences are combined to form meaningful wholes. We can look at discourse as connected language.

This concept developed from the field of sociolinguistics when Labov, in the 1960s, looked at speech styles in New York. It was also used in interactional sociolinguistics, and was studied by several fields, including anthropology, history, sociology, linguistics, psychology, education, and, in the 1990s, speech-language pathology.

Genres

There are different discourse genres. The most popular one used in speech-language pathology is narrative discourse. Simply put, narratives are stories. We use these when we ask our patients to describe picture sequences, or have them read a paragraph and then recall the story later. We can also look at this by asking them to tell the story of their stroke, or a memorable experience, or a frightening experience.

Another type of discourse is procedural discourse. One of the more popular elicitation methods used in research is, "Tell me how to make a peanut butter sandwich"; and the patient is asked to give the steps.

We will cover conversational discourse later on. This is when the person with aphasia is conversing with another person.

We also have expository discourse, wherein there is one subject, with details that are logically related to that subject and that may not necessarily be in chronological order. Say, for example, we ask our patient to talk about stroke. They can discuss the symptoms of the stroke, the causes of the stroke, and the risk factors behind stroke. These are not chronologically related - unlike a story - but they all revolve around one topic.

Why Consider Discourse in Aphasia Rehabilitation?

Why is it important that we consider discourse in aphasia rehab? Well, from the patient's perspective, patients with aphasia choose to speak about their life experiences. They want to reconnect with their families and focus on communication that helps them with activities of daily living. If you were to put yourself in your patients' shoes and you only had very limited language, where would you want to put all your effort? This idea was underscored in the 1970s by the work of Holland and Sarno, wherein they would emphasize functional communication rather than linguistic accuracy for persons with aphasia. Persons with aphasia “communicate better than they talk,” in that there is very little relationship between the severity of the language impairment and the ability to communicate in daily life.

Also, from a clinical perspective, we want to get a comprehensive analysis of what our patients can and cannot do by examining how they perform in social contexts. Another important reason to consider discourse is that discourse allows us to examine the cognitive and linguistic aspects of expressive language via natural forms of communication.

I would like to unpack this thought. What are the various cognitive tasks that are required of us when we engage our patients in discourse? Well, discourse is a complex task that involves executive skills, working memory, and long-term memory. For example, say you were to ask your patient to talk about his wedding day. The patient would need to recall information from his memory. He would need to select what to include and what not to include. He would need to remember what has been said and try to organize what he is about to say, while accounting for what the listener may or may not know and also while maintaining that same topic.

Discourse can also be used to identify meaningful changes in communication that may not be detected on standardized battery tests.

Studies on Discourse Intervention in Aphasia

Let’s look at what we know so far about discourse. In 1991, Osiejuk did a single case study on discourse therapy, and found that discourse therapy increased the amount, complexity, and organization of information when patients were asked to produce stories and procedures, despite grammatical and reference errors. In aphasia, there is a tendency for the patients to have anomia (naming difficulties), so they tend to resort to referencing using indefinite pronouns such as “he, she, it, that, and this.” Osiejuk found that despite these errors, the persons with aphasia are still able to tell a story and give procedures.

Kempler and Goral (2011) tried to compare drill-based versus communication-based treatment for aphasia. In their study, they had individuals name verbs. They would show a picture card and the person would say, “eat” or “sleep” or “drink” in their drill-based treatment. In the communication- or discourse-based protocol, the individual was asked to request an object, or a card. They found that the drill-based treatment had a small positive effect on verb naming, whereas the communication-based treatment had a pronounced effect on sentence and narrative structure. They thought that the communication-based approach resulted in better outcomes because it allowed participants to exchange information and use intact conversational and pragmatic skills in order to get their message across.

More and more studies are being published that compare discourse treatment for word retrieval to basic naming tasks. What they are finding is that after discourse treatment - as opposed to object-naming treatments - patients show more communicatively appropriate responses and improved word retrieval abilities. Another important study, done in 2016 by the Max Planck Institute, used crossover randomized controlled trials. They had patients name cards, and then the treatment would be randomized and they would cross over to more discourse-based tasks. They found significant improvement in language performance on standardized aphasia test batteries when verbalizations were produced in the context of communication and social interaction, as opposed to during naming tasks.

Neuroimaging studies. What might be the reason behind this? A series of studies done by Egorova and colleagues (2014, 2016) showed increased brain activity when utterances are embedded in relevant communicative contexts. These studies compared requesting objects from a person to simple naming of pictures, and found stronger neurophysiological and neuroimaging responses in the brain when patients are engaged in communication tasks. Broca's area and the precentral gyrus are more strongly involved when a person is asking for an object in a communication context, versus during simple naming tasks. In other words, the human brain benefits most when linguistic forms are practiced in communicative interaction.

Discourse and personal relevance. The keyword here is relevant; relevant communicative settings. A study by Holland and colleagues (2010) suggests that treatment should emphasize topics that are very personally relevant to the individual. According to them, persons with aphasia derive meaning from sharing personal stories. There is a preference for sharing a stroke story or a memorable experience as they engage in conversation. They may want to converse with their family more, especially grandchildren, or to seek and provide information, or to discuss interests. Later on, we will be discussing both narrative and conversational discourse.

Narrative Discourse and Aphasia Rehabilitation

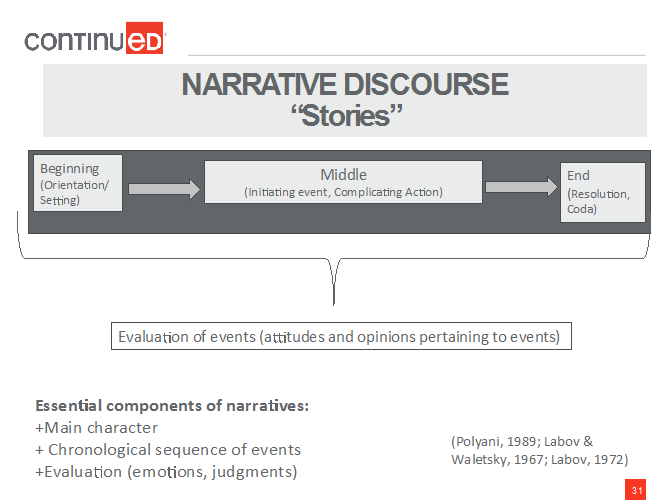

What are narratives? Simply put, narratives are stories. The stories have a beginning, a middle, and an end (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Components of a narrative.

But in addition to the simple narrative structure, we also have an evaluation. We evaluate; i.e., we provide attitudes or opinions pertaining to what we experienced.

The main components of narratives are that they have main character, following a chronological sequence of events, and they evaluate via emotions and judgments.

Why Study Narratives?

Why study narratives in aphasia? Narrative stories play a central role in almost every conversation. They are also ecologically salient, meaning that they are necessary communications that sustain day-to-day interactions. They also have multiple functions. We produce stories to share and evaluate our life experiences. We also use them for reminiscing. The elderly use stories to transmit wisdom. We also use narratives to tap autobiographical memories in various memory systems. There are more and more studies that show how, among the elderly, auditory and visual memories are relatively preserved when the elderly talk about meaningful personal experiences. Say, for example, an older person is talking about a memorable vacation. What she may retain are the sights and sounds, or the music that was related to that vacation.

Another reason why we study narratives is that it is a means of studying communicative competence -- the ability to successfully get the message across via words, gestures, or writing. Narratives enable clinicians to appreciate cultural patterns and individual variations in communication. In a study that my colleagues and I (2016) did on stroke, stories, and bilingual aphasia, we discovered certain themes that were unique to the culture, such as whether a person comes from a collectivistic - or family-oriented – culture or an individualistic culture, the role of the family in making decisions, and even the patterns of code switching in bilingual aphasia.

Narratives also allow the clinician to see the person and not just the diagnosis. When persons with aphasia are given the opportunity to reflect on and express their identity, we see who they are and their perspectives on life events.

Eliciting Narratives

So, how do we elicit these narratives? Tasks and activities must represent daily communication contexts that are naturalistic or realistic. We can ask them what their favorite topics are, pastimes, or significant milestones in life. We can also tap into experiences in a patient's memory peak or memory bump – typically, memories from late adolescence into early adulthood, such as a first job or the first child or the first marriage - which tend to be preserved. Rubin, a psychologist who specialized in memory, conducted several studies that document how the elderly tend to remember events in the memory peak.