Editor's Note: This text is a transcript of the course Disability Inclusion: What Healthcare Providers Need to Know, presented by Kathryn Sorensen, OTD, OTR/L, ADAC

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Describe ways to ensure disability is included in the DEI conversation.

- Identify at least 3 ways to support emotional, social, and family impacts on disability.

- List ways social stigma and societal attitudes impact people with disabilities.

Introduction

Thank you all for being here today and for having me. I am an OT and professor, and I have osteogenesis imperfecta (OI). I'm hoping that you'll learn more about that in this course; however, what works or doesn't work for me may not be applicable to clients you have with osteogenesis imperfecta. If you're not familiar with this, it is also known as brittle bone disease. I have had it since birth. It is genetic. There are different varying degrees of severity of OI. I'm on the middle to less severe side of things.

This past weekend, I was visiting my nephews, who are 4 and 1 1/2 years old. I was tackling them, picking them up, and carrying them with my wheelchair. People always wonder if they can hug me or fist-bump me. Yes, you can do that. But it has had a profound impact on me as far as my mobility goes.

Growing up, I experienced multiple fractures in my femurs, resulting in permanent damage to my growth plates. Consequently, I now use a wheelchair full-time, primarily for safety reasons and to maintain my physical fitness, particularly my well-defined biceps – a topic that often comes up in my presentations.

Interestingly, in the era of virtual meetings, like Zoom, when remote work became widespread, I sometimes forgot to mention my disability. You currently see me seated at my office desk, but during an in-person encounter, my wheelchair use would be apparent. There was no need for me to make a deliberate disclosure. At the outset of the pandemic, there were moments on Zoom when I'd throw in a wheelchair-related joke, catching some people off guard, especially those who didn't know me well. It prompted me to pause and say, "Oh, by the way, I have a disability and use a wheelchair." So, the pandemic served as a reminder for me to disclose my obvious physical disability. I want to emphasize that when I do make wheelchair jokes, it's never intended to be mean-spirited. I make them because I use one.

Growing Up With a Disability

With that clarification, let me share a few pictures of myself. I'm 41 years old and grew up in northern New Jersey, just outside of Manhattan. I was born with Osteogenesis Imperfecta (OI). Throughout my life, my legs have endured a significant amount of trauma. While I haven't experienced an excessively high number of fractures, considering OI standards, maybe between 10 and 15, I have undergone more surgeries than I've had birthdays – a total of over 47 surgeries.

Here's a picture of me in kindergarten for context. I'm the person on the far right, in the front row, wearing the purple striped shirt.

Figure 1. Presenter in kindergarten.

As you can see in this photo, during my kindergarten years, I stood at roughly the same height as everyone else in my class. Back then, I didn't rely on a wheelchair or any mobility devices. For those of you who work with kids, especially in elementary or middle school, I'll be sharing more about what I wish healthcare providers would be aware of, as well as my personal story.

The most challenging period for me began around third grade and continued through high school. Third grade was the year when I first became aware that people were noticing my differences. In kindergarten, I knew I couldn't run alongside the other kids, but I didn't fully comprehend the implications of having a disability. As I grew older, people often asked me when I first became aware of it.

I had always been aware of my condition, but it wasn't until third grade that I realized others viewed it negatively. That's when people started saying things like, "I don't want to play with you because you can't participate in certain activities, like riding a bike." For those of you working in the school system, I want to highlight the profound impact my third-grade teacher had on me during this period.

She was a true gift. When I couldn't join my peers outside due to a broken leg or other limitations, she would assign me special projects in class. These tasks ranged from organizing crayons by color to cutting out heart shapes for Valentine's Day activities – seemingly simple things, but they made a world of difference to me. I always felt a sense of love and importance during those moments when I had special projects to work on, not because I was excluded from recess activities but because I was given a unique task. Even during events like field day, my gym coaches would entrust me with the whistle or have me hold a clipboard. My teachers consistently found creative ways to ensure I could participate in some capacity. This support meant the world to me, especially as I navigated my own emotions about my peers noticing my differences.

I share this experience to encourage all of you to explore ways to help the children and clients you work with feel included in experiences with their peers. It can make a world of difference in their lives.

One thing I wish people had understood back then is that children, even those without disabilities, can struggle significantly. Nowadays, it's even more evident. Reflecting back, I wish I had been in therapy. I wish my parents had encouraged me to seek therapy or that someone had recognized the challenges I was facing and suggested it.

Osteogenesis Imperfecta is a genetic condition; I inherited it from my dad. Interestingly, both my older brother and younger sister also have mild manifestations of OI, but unlike me, they don't experience any mobility impairments. Interestingly, neither my brother nor my sister has ever experienced a fracture due to OI. While my dad did have a couple of orthopedic issues during his childhood, it wasn't as pronounced as what I faced daily. It was a unique and often challenging experience for me, and I understand that it was difficult for my parents as well. Witnessing their child undergo numerous surgeries and cope with pain took a toll on them emotionally. At times, they struggled with their own feelings, which occasionally made it challenging for them to provide the support I needed.

When people inquired about how I was doing, I was often labeled as a "trooper." While this might have made things easier for everyone else, it meant that I frequently put aside my own thoughts and emotions in the process.

When I discuss this topic, I'm often asked, "How can you tell if a kid is struggling?" My advice is to assume that they are, especially in today's world with the internet and social media. Back when I was in elementary school during the late '80s and early '90s, we didn't even have the internet, and that was challenging enough. I can only imagine how much more difficult it is now, with the barrage of societal messages suggesting that disability is a negative aspect, promoting feelings of inadequacy, and encouraging constant comparisons.

People often inquire about aspects like whether I had a birthday party that year, and the answer is probably not. Attending birthday parties? Rarely. Instead, consider asking about friendships. What did I do with my friends? I'd mention sitting together at the lunch table, but truthfully, they weren't genuine friends. They were just people I sat with, listening to their weekend plans, only to hear about their weekend activities on Monday – activities I wasn't invited to because of my disability.

Many kids with disabilities, including those I've spoken to, are into online gaming. It's wonderful that they have an outlet and a sense of connection, but it's not a substitute for the experience of interacting with peers in person and forming genuine connections at school. I cannot stress enough how crucial it is for all of you working with individuals with disabilities to ensure that they have someone to talk to. Understand that not everyone will immediately seek it, and not every parent may initially agree with it. However, the best course of action is to at least extend the offer and encourage it.

UNC Rowing Team - 2003

During my undergraduate years, I enrolled at the University of North Carolina. I decided to try out for the rowing team, motivated by a bet with my physical therapist. He bet me that I would successfully pass a sports physical, something I never believed I could achieve. He actually said to me, "If you pass that sports physical, and I bet you will, I'll take you to a Yankees game."

As a devoted Yankees fan who grew up in northern New Jersey, I knew what I wanted from that bet. I could see myself seated behind home plate, possibly in the dugout, and enjoying an ice cream served in one of those iconic mini baseball hats. My physical therapist simply responded with, "Whatever you want." With that in mind, I decided to go for the sports physical, fully prepared to be laughed out of the doctor's office.

When the doctor said, "You're cleared." I couldn't believe it. I had OI, and she was giving me the green light for sports. She clarified that I wasn't cleared for contact sports but emphasized that I could absolutely join the rowing team. At that moment, I realized that I had made an error in the bet. I hadn't bet on trying out for the team; it was merely about passing the sports physical. So, I arrived at UNC and took my chances, trying out for the rowing team as a walk-on.

At this age, my arms were unbelievably toned. I had initially assumed I would be rowing, but it turns out that rowing primarily engages the legs, and I stood at just 4'1" and weighed around 105 pounds. So, when I walked onto the rowing team scene, I confidently announced, "Hey, everyone, I'm here to try out for the rowing team!" Their response, however, took me by surprise.

They asked me, "Can you yell?" I responded, somewhat puzzled, "What does yelling have to do with rowing? Of course, I can yell. I'm from New Jersey, and I have a brother and a sister." Then came another unexpected question, "Can you swim?" I chuckled, thinking we'd be in a boat on the water, and replied, "I thought we'd be in a boat. But yes, I can swim."

To my amazement, they explained that they needed me as a coxswain – someone small, lightweight, who could yell and swim. Once again, I wondered about the swimming part, but I agreed, and before I knew it, I became the coxswain, the person at the back of the boat responsible for making calls and steering.

It turned out that I was the perfect fit for the coxswain role because, in the boat, you essentially act as dead weight, and the lighter you are, the better. So there I was, standing at just 4'1", as a varsity athlete at the University of North Carolina.

Here is a fun fact that tends to find its way into every presentation I give: I actually hold the unofficial record in the weight room for the most pushups in a minute. Yes, I managed to beat sports legends like Michael Jordan, Vince Carter, and Mia Hamm. Since it's an unofficial record, it can never be officially broken. If any of you happen to know Michael Jordan, Vince Carter, or Mia Hamm, please do let them know that you know someone who outperformed them in an unofficial athletic competition.

After graduating from UNC as a varsity athlete, an achievement I had never imagined was possible given my disability, I decided to pursue a career as an occupational therapist. This choice was influenced by my physical therapist and doctors, who provided me with the encouragement and support I needed.

I then headed to the University of Southern California (USC), and at that time, I was using crutches full-time. Suddenly, I was enrolled in classes called: Physical Disabilities. It was a bit overwhelming because I had never truly addressed the emotional, social, or mental aspects of my disability before.

September 20, 2005

My parents came out to USC to visit me for the weekend, and I had just dropped them off at LAX (Los Angeles International Airport). When I returned to my apartment, which was on the main campus of USC, it was raining. I was still using crutches because I had recently undergone surgery to replace my right MCL (medial collateral ligament) on my right knee. Consequently, all my weight rested on my left leg, and as I stepped out of my car, I fell and fractured my left hip. The date was September 20, 2005, a day I'll always remember.

I remember thinking, "Oh no, I just broke my left hip," and my parents had already left, unable to return immediately to help me. My friends rushed me to the hospital, where I had just spent a week before undergoing surgery to have screws implanted in my hip.

When I returned to my apartment, my life had changed dramatically. I now relied on a wheelchair full-time because I quite literally didn't have a leg to stand on – and that's not a pun. It was the harsh reality; I had recently had my right knee surgery, and now I had a broken left hip. This transition from being ambulatory on crutches, free to explore places like Italy, where I had traversed all seven hills of Rome without any physical limitations, to suddenly being in a wheelchair was a monumental game-changer. I had to learn how to operate a vehicle with hand controls and adapt to tasks like grocery shopping from a wheelchair.

Although I had been born with a disability, September 20, 2005, marked the day when I truly experienced and comprehended the profound limitations it could impose on my life. Following that life-altering incident, I was very angry and in a dark place. I want to emphasize that suicide is a profoundly serious matter, and although I didn't have an active plan, I did think about it. I questioned my existence, wondering why I was here, especially when it felt like a series of unfortunate events kept unfolding before me.

I internalized this belief as a child and young adult, including my time in graduate school. Securing clinical internships during grad school proved challenging due to my preexisting hip injury, a decision I now fully understand. However, I felt a sense of rejection and struggled to find my place. Eventually, I settled for internships in California, as my cousin resided in the San Jose Bay Area, and I opted to live with her for a while.

After starting a new job in San Jose, I joined a local wheelchair tennis team to stay active. Within a few weeks, my coach recommended I compete in a tournament in Napa despite my beginner skills. There, I met an opponent who volunteered with an organization that distributes wheelchairs globally. She invited me to join a trip to Thailand in January 2008. I was anxious about the unfamiliar food but didn't consider the challenges of international wheelchair travel with strangers.

Thailand 2008 - The Moment My Life Made Sense

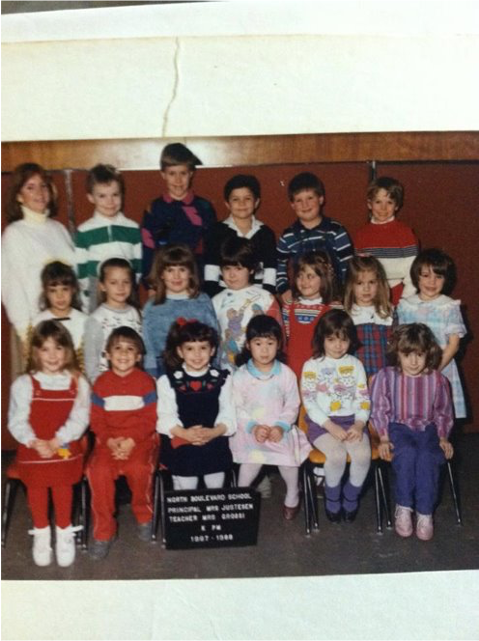

Our first stop in Thailand was an orphanage for children with disabilities to donate wheelchairs. In the photo below, I'm in an orange shirt fitting kids into wheelchairs. Drawing on my OT background, I intuitively knew which chair would work best for each child. I noticed a girl who I immediately recognized as having OI like me. While I had met others with OI, this was the first time I could directly help someone with the same condition. It was incredibly meaningful to connect with her through our shared disability and improve her mobility and independence.

Figure 2. Presenter and young girl in wheelchair.

At that moment, everything came into sharp focus. I had an intense physical reaction - ringing in my ears, tunnel vision, and a burning inside. Initially, I thought I was having a medical emergency, but then I clearly heard a message that this experience was the purpose of my disability. My OI wasn't random bad luck or something I deserved, but a gift. This was the day my life made sense - I realized I could uniquely connect with and help others with disabilities like the girl in the photo. She helped me see that my condition equipped me for a meaningful purpose. I finally understood why, and had a picture of the moment it all came together.

After this trip, I was invited to participate in more service excursions and public speaking opportunities about my experiences. I began finding my passion and realized I wanted to pursue becoming a professor. This inspired me to go back to school to earn my clinical doctorate.

Basilar Invagination

In 2015, while home for a wedding, I fell in the middle of the night and hit my head on a nightstand. My left arm went numb - a bad sign. Back in California, doctors initially thought it was a pinched nerve, but the numbness didn't fully resolve. It turned out I had a condition called basilar invagination, causing compression in my neck, vertebrae, and skull. This was unrelated to my fall, but the head injury led to swelling that allowed its detection. Otherwise, it could have gone unnoticed for years until an accident caused catastrophic spinal cord damage.

I ended up needing neck fusion surgery. For three months, from April to July 2016, I was in a halo brace for stabilization. Though scary at the time, finding this condition may have prevented a severe injury down the road. Once again, my disability journey led me to growth. It was horrific, yet also one of the most meaningful experiences of my life. I felt truly loved and supported during those three months in the halo brace. Friends brought meals every other day, helped bathe me, did my laundry - they just showed up. Seeing people rally around me in my time of need was incredibly moving. I realized my value and worth as a person and how my disability only strengthened my relationships. It was a tremendous gift to feel that outpouring of love, which I hadn't fully understood before.

In 2017, I graduated with my doctorate and joined the faculty at UNC, moving back to the East Coast. Things were stable until 2020, when I developed double vision. It turned out my basilar invagination had compressed the abducens nerve controlling lateral eye movement. Finding care was challenging during the pandemic, but I located a surgeon at Northwestern who had performed my needed procedure on others with OI.

On October 8, 2020, I underwent anterior and posterior cervical decompression surgery to address the basilar invagination. After being given paralysis medication for intubation, my throat unexpectedly swelled, and the doctors couldn't get the breathing tube down. They called a code blue and started CPR as my blood pressure dropped. I had to undergo an emergency tracheotomy and was put on a ventilator. I awoke in the ICU, unable to speak, restrained, and confused about what happened. It was very traumatic.

The surgery was postponed for a week to let my tracheotomy heal. The 16-hour anterior decompression was ultimately successful, but the intubation complication was frightening and risky. I returned to the ICU for recovery.

Three days later, I underwent the posterior decompression. Removing the tracheotomy tube took longer than expected. I then developed a blood clot in my thigh. In total, I spent nearly a month in the Chicago hospital during the pandemic with strict visitor limitations. It was an incredibly challenging time.

But what mattered most was having caring healthcare providers. They became my support system when I was alone and recovering from multiple complications on top of complex surgery. I had one friend and later my sister with me. The psychiatric team consulted me in the ICU before I could even speak. I'm open about struggling with depression and anxiety in addition to OI. My first communicable question, after making some sarcastic joke to show my cognition was intact, was whether they had an IV version of my SNRI medication. I knew that without stabilizing my neurotransmitters, I wouldn't be okay after going nearly 4 minutes without oxygen. When they said they didn't have it yet, I panicked - the only time during those three harrowing weeks.

The psych team was essential. They quickly got me an IV version of my critical SNRI medication to stabilize my neurotransmitters. Once my mental health was addressed, I could cope with the rest. Mental health is more important to me than physical issues like bone density. I still meet weekly with my therapist - it's the most important thing I do for myself. I wish this option had been raised earlier, though I may not have been open to it before. Just knowing therapy was available would have been huge.

I'm adjusted to my disability after 14 years of therapy processing my experiences, not because of my childhood. Mental healthcare is lifesaving yet often overlooked, especially for those with disabilities facing medical trauma. I cannot stress enough the importance of offering psychological support.

Overview

To understand me and where I'm coming from, there are seven things that I wish healthcare providers knew in any setting:

I.The hardest part

II.Accessibility matters

III.Dream about the future

IV.Keep the bar high

V.Listen

VI.Never underestimate your impact

VII.The best part

The Hardest Part

People tend to view my disability through a biomedical lens. The biomedical view of disability is limited. It focuses solely on what is "wrong" with my body, like my bone density. But disability is more than just medical issues. There are other important perspectives, like the social model. This recognizes that societal barriers and stigma also disable people with differences. For example, when I go to order food and get passed over because people assume I couldn't be there alone, that's the social model.

In addition to social barriers, environmental barriers are another key aspect of the disability experience. Inaccessible built environments prevent participation regardless of one's capabilities. For example, I may be able to drive independently, but without a curb cut, I cannot get onto the sidewalk from my car. Or a missing accessible bathroom stall prohibits my use of a facility. In these cases, it is not my osteogenesis imperfecta preventing access but rather lack of accessibility accommodations that should legally be provided.

Then, there is the functional model. An example of this is having a pinky amputated. This may not be the end of the world for some people, but for a classically-trained piano player, it would be a significant disability and a life-altering change if they can't make a living due to losing their pinky. So, these are the four primary perspectives on disability.

Attitudes of Healthcare Providers. The majority of healthcare providers are trained in the biomedical model, while individuals with disabilities make up nearly a quarter of our population, with many of them facing invisible challenges. Notably, higher prevalence rates of anxiety and depression have been observed among this demographic.

Even within the healthcare system, where we all work, people with disabilities encounter discrimination. They frequently report negative experiences, and I have personally experienced this bias as well. The two situations where I feel the most social discrimination are at the grocery store, where people often express undue admiration for simple tasks like buying bread, which can be frustrating. Moreover, at the doctor's office, the challenges are more obvious. Accessing a doctor's office and using examination tables can be extremely difficult, as they are often not designed to accommodate individuals in wheelchairs.

People with disabilities often miss out on important healthcare screenings like cancer and STD checks because there's this mistaken belief that they're not in relationships with any kind of sexual activity. It's like people think that just because you have a disability, you're not a normal person who might need these screenings. This misconception means they don't get the attention they should, and they often face physical barriers that keep them from accessing these essential services.

Medical schools often overlook the importance of disability education. While they extensively cover illness and injury, disability is frequently left out of the curriculum. Additionally, many of these programs are designed by individuals who don't have disabilities themselves, which raises some concerns.

I'd like to highlight a couple of recent studies, one in 2021 and another in 2022, conducted by the same group. In these studies, they surveyed 714 practicing physicians from across the United States. Brace yourself for this unsettling finding: A staggering 82.4% of these physicians believed that individuals with significant disabilities have a lower quality of life compared to those without disabilities. As someone who identifies as having a significant disability, I struggle to find the right words to respond to this statistic. It makes me feel unseen and undervalued.

It's disheartening to note that only 40% of physicians consider themselves competent enough to provide the same level of care to people with disabilities, not even going above and beyond basic equal care. Additionally, just half of them agreed that they genuinely welcome patients with disabilities, and a mere 20% or 18% acknowledged the prevalent unfair treatment of people with disabilities within the healthcare system. It's quite astonishing and underscores the unfortunate reality that healthcare providers, in this case, physicians, often lack an understanding of the experiences faced by individuals with disabilities.

There is an urgent need for substantial improvements in disability education within medical training and, I would argue, across all healthcare professions. Some individuals have expressed the view that accommodations for people with disabilities are burdensome. In fact, one specialist even went so far as to claim that people with disabilities tend to make a big deal out of nothing and are an entitled population.

When it comes to something as basic as being able to use the bathroom like anyone else, yes, I do believe I'm entitled to that, and I won't shy away from that assertion. It's true that we've encountered patients who may exaggerate symptoms or try to exploit the system, and these cases can cast a shadow over the rest of us. However, in general, I don't know anyone with a legitimate disability who is asking for more than equal access to facilities and spaces, including the ability to use the restroom like everyone else.

Half of doctors have been found to harbor negative attitudes towards individuals with disabilities, which can result in delayed or inadequate care for their patients. To those 82% of doctors who believe that people with disabilities receive the same level of healthcare as others, let me share an example from my own experience. I reside in North Carolina and receive healthcare services at a university, and I had an encounter just two months ago that illustrates this issue. Last year, at the age of 40, in 2021, I had my first mammogram. When the time came for my follow-up mammogram this year, the renewal letter arrived, offering various new locations for me to choose from, along with an invitation to schedule my appointment online. As I went through the online process, it asked me questions like, 'Have you had a mammogram before?' and 'Are you part of the university system?'

Then came the unexpected question: 'Do you use a wheelchair?' I wondered why this was relevant but answered 'yes.' It then asked, 'Can you stand unassisted?' This question left me puzzled. I thought, 'What do they mean by unassisted? I can stand if I'm holding onto something for about five minutes or without support for a minute or two.' I decided to be honest and selected 'no' since I technically needed some form of assistance or contact guard, even if it was just my own wheelchair. Surprisingly, after that, it provided only four locations where I could make my mammogram appointment.

I was holding a letter that mentioned seven new locations, so I retraced my steps within the system, changed my response to 'I don't use a wheelchair,' and suddenly, I had 11 options for appointment locations, including one conveniently close to my home. However, the four options given when I indicated I used a wheelchair were all around half an hour from my house, requiring me to pass by three other locations just to reach one that was wheelchair accessible.

So, I decided to give the university a call and express my confusion, saying, 'What's going on here?' Their response was, 'Well, you know, we can't guarantee your safety at those other seven locations, so for safety reasons, we've restricted you to these four.' To which I retorted, 'You've just recently opened up seven brand-new locations; they have to be accessible.' They countered with, 'Well, they are accessible, but we can't ensure your safety there.' I pressed further, asking, 'What's the difference between the four you're offering and the other seven?'

Their explanation was that the four designated locations had two mammogram technicians on hand, while the other seven had only one. In other words, because I use a wheelchair, they insisted I had to go to a location with two techs. That's when I reminded them that such a practice is illegal. The law requires healthcare providers to offer the same level of service to everyone at every location. I made my case to them, and they promised to review their policy. I haven't had a chance to follow up this week to confirm if they've made the necessary changes, but it's a reminder that sometimes we have to stand up to the medical system and assert that certain practices are both illegal and discriminatory.

The irony of the situation hit me when I actually went to get my mammogram. Surprisingly, I didn't even have to leave my wheelchair during the procedure. The mammogram machines had a low enough position that made it entirely feasible. I couldn't help but wonder why they hadn't considered this in their initial assessment. To make it even more frustrating, the location I visited was among the seven initially denied to me.

Their explanation was equally baffling. They said, 'Well, sometimes people can't lean over on their own.' It was clear that if they wanted to ask a pertinent question, it should have been, 'Can you lean over on your own?' instead of the incorrect, 'Can you stand unassisted?' The fact that they thought it was appropriate to direct individuals using wheelchairs to different locations than everyone else was not only wrong but completely illegal.

This incident underscores the importance of healthcare providers being aware of these issues. First, we must ensure that such discriminatory practices are not occurring in our own workplaces. Second, we need to advocate for accessible healthcare experiences in the facilities we visit for our own medical care. Sadly, this topic remains largely overlooked within healthcare professions, but it represents a significant concern for people with disabilities.

Discrimination at the Doctor's Office. Another frustrating aspect of my experiences in doctor's offices involves instances where I feel discriminated against. One of these situations is when I'm pushed into a waiting room without anyone even asking if I need assistance. It's like they call my name, 'Katie,' and I turn to grab my jacket, and suddenly, I'm being moved involuntarily. I'm thinking, 'I'm from New Jersey; you don't just push me around without asking." In general, people sometimes talk to me as if I'm a child. They'll say things like, 'Oh, look at you; you're so cute.' But when you're a nurse about to give me my COVID vaccination, talking to me like I'm in a stroller, my inner Jersey girl wants to say some very unkind things.

DEI Efforts. In broader discussions of diversity, equity, and inclusion, disability often takes a backseat. Even though I have a deep affection for my university, UNC, I must point out that it serves as a prime example of how diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives are abundant for nearly every minority group, except for people with disabilities. It's not a criticism but rather an illustration of the pervasive gap.

Interestingly, while 90% of companies claim to prioritize diversity, only a mere 4% include disability as part of their diversity efforts. This glaring omission is telling. Research consistently demonstrates the undeniable connection between disability and feelings of loneliness. It's not merely about physical isolation, such as in my case with OI, that limits my mobility; it's also about the loneliness that stems from the absence of disability in conversations about diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Stigma. Shifting slightly, it's worth noting the distinction between congenital and acquired disabilities. A study has shed light on the fact that individuals with congenital disabilities, those present from birth, can face even more pronounced stigmatization than those who acquire disabilities later in life. In my case, despite being born with OI, I felt a heightened sense of stigma when I began using my wheelchair full-time. It's almost as if I've experienced both being born with a disability and acquiring it, and I can attest that the former has been significantly more challenging.

Adapting to life in a wheelchair posed its own set of challenges, but being perceived as someone with a disability fundamentally altered how others interacted with me. It's a starkly different experience from individuals who may have acquired a disability later in life due to a spinal cord injury from a car accident or other factors. Understanding these nuanced distinctions within the disability community can be complex.

Basic Etiquette. Healthcare providers often make assumptions about what I can or can't do, especially when it comes to things like getting on the exam table. I wish they would just give me a moment to demonstrate how I handle things. Offering assistance or asking if I need help is perfectly fine, but assuming that I can't do something is incredibly frustrating.

Talking. As SLPs, you are well aware of the different communication needs of your patients. When someone has a language impairment, you don't automatically raise your voice or slow down your speech. Similarly, if there's a translator or interpreter present, you know to address the person directly, not their interpreter. Also, there's no need to change your tone to speak to the individual as if they were a child. I'm 41 years old, and I outgrew that phase about 39 years ago.

Communication. It's crucial not to assume that just because someone has expressive aphasia, they also have receptive aphasia. Furthermore, kids with disabilities often comprehend more than we give them credit for. I remember in fourth grade, I could explain what a derotational osteotomy was and name all the anatomy involved. People sometimes underestimate the understanding and knowledge that kids with disabilities possess.

When it comes to addressing patients, it's essential to use their names, not just refer to them as 'the OI in room four' or any other condition. I'm Katie, or simply the patient in room four. It's a simple yet meaningful gesture that acknowledges our individuality.

As for interacting with someone in a wheelchair, there's no need to go to extreme lengths to adjust your posture, like squatting or kneeling, unless it's comfortable for both of us. If you're at ease, I'm at ease. Just asking if I'd like a chair or some other form of adjustment is considerate without making it a spectacle. Ultimately, it's about treating people with disabilities as you would anyone else—respectfully and inclusively.

Accessibility Matters

We do not talk about the ADA enough in healthcare. We're not talking about disability enough, and accessibility issues are pervasive. Take, for instance, the typical check-in counters you find in many places, including medical offices. These counters often have a lower section that should ideally be 36 inches high, in compliance with the ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act). However, what I frequently encounter, especially in doctor's offices, is that while they have these lower counters, they're often unstaffed.

Alternatively, I may approach the higher part of the counter, but the computer screen is so high that I can't see over it, and no one comes over to assist me at the lower counter, as they should. Often, these lower counters end up cluttered with plants, brochures, or other items, rendering them inaccessible for those who need them. Accessibility truly matters.

As an occupational therapist, I consistently emphasize the importance of enabling people to engage in meaningful activities. For example, I have a deep passion for sports, and two years ago, I purchased a $100 ticket to a basketball game at the university. The sports facility has a capacity of 21,000 seats, yet they only allocate eight wheelchair-accessible seats. Shockingly, they were selling tickets for people in wheelchairs for seats that weren't accessible. The result? Throughout the game, everyone around me stood, and I couldn't see anything. It was a frustrating experience, and I couldn't help but raise my concerns. Fortunately, they are working on addressing these issues, but incidents like this are far too common.

Another thing that can drive me a bit crazy is encountering wheelchair-accessible bathroom stalls that have doors that open inward, making it impossible to get in and close the door behind me. To tackle this issue, I've taken to carrying little wrenches with me. When I encounter such stalls, I remove the stopper, open the door, and flip the stopper around, effectively making it accessible.

Here's a prime example: a seemingly brand-new parking lot or a well-maintained one, possibly belonging to a newer building. They have the ADA parking spot and a loading zone on the side—great. However, there's no curb cut. So, I find myself having to navigate all the way around the building, often in the midst of traffic, just to reach a curb cut. It feels counterproductive and, more importantly, unsafe.

Independence. Some examples of how I am independent include having a front-loading washer and dryer, which makes doing laundry much more manageable. My stove has its knobs conveniently placed on the front, eliminating the need to reach over hot burners. As someone who loves cooking, this feature is a game-changer.

In my kitchen, I have a pullout counter at a lower height, specifically designed to accommodate my needs. Additionally, I've installed a grab bar in my bathroom, although I realized I needed one closer to my tub, so I added a standing grab bar there. These seemingly minor modifications play a significant role in promoting independence and improving the quality of life for people with disabilities.

It's surprising how many therapists and healthcare providers may not be fully aware of the intricacies of ADA laws and related regulations. One such law that can significantly benefit people with disabilities is the Fair Housing Act. Under this law, individuals living in apartments have the right to request various accommodations, and apartment complexes are obligated to provide them free of charge, such as:

- Front loading washer dryer

- Stove with knobs on the front

- Adding grab bars

- Lowering closet racks/cabinets?

- Reserved parking spot even when spots are not reserved for other residents

- Charging upper unit price to a lower unit when the upper unit is not accessible

Even if a client's challenges at home aren't directly related to their therapy or healthcare needs, it's crucial to inform them about the Fair Housing Act and the rights they possess.

People are always inspired to know that I drive. I'm 41, single, and my van is my dream car. I use hand controls, and I just want you all to know that things are possible. Every public transportation system must have what's called paratransit. So, make sure you understand that your clients might be missing a lot of therapy by not being able to come to your clinic. It may not be that they're defiant; they simply might not have access to transportation. Knowing about these possibilities is crucial for healthcare providers to be aware of the services and laws that protect people with disabilities.

Being able to engage in activities like playing tennis and skiing is a great joy for me. My youngest nephew loves being held and "driving" my Firefly. My older nephew is a big fan of going to the park. They live in Manhattan, where there's a conveniently accessible park near their house. Thanks to its accessibility, I can easily accompany Harrison up the slide, making it a fun experience for both of us.

So, in your community, do you happen to know if they're constructing a new park? If they are, it's essential to check if it includes a ramp for easy access to the top. Some playgrounds only provide a small transfer landing, but after that, people with wheelchairs often face challenges, as they may have to crawl to fully enjoy the playground.

Are you ensuring that your communities are accessible, not just as a speech therapist for your clients but also for your neighbors and future neighbors? Consider the possibility that your future grandkids might want to visit, and if you ever end up using a wheelchair or face mobility challenges; accessibility becomes even more crucial.

As an example, at UNC, we have the iconic old well, and I was the first person to convince the school to install a ramp, allowing people with disabilities to take a drink from it. These small changes matter greatly.

Speaking from personal experience, I love to travel. I've been to places like the Great Wall of China, Paris, and Australia. However, many of these destinations are not accessible to people with mobility challenges. But thanks to my mobility device I want to emphasize that I'm not promoting or profiting from it. I want you to know that having access to innovative mobility devices like this can make a tremendous difference in the lives of people with disabilities. It opens up a world of opportunities and experiences that would otherwise be inaccessible.

I want to strongly encourage all of you to familiarize yourselves with the basics of the ADA law, not only for your clients' benefit but for the betterment of your community as a whole. It's important to understand these laws and their implications.

To echo a familiar phrase, it's essential that if you see something that's not accessible, speak up. The ADA places the responsibility on individuals with disabilities to identify and report inaccessible conditions, and this is a significant shortcoming. However, if more people like you and I understand these laws and are willing to advocate for accessibility, we can hold establishments accountable and drive positive changes.

By collectively raising awareness and insisting on accessibility, we can make our world more inclusive and welcoming for everyone. It's a responsibility we all share, and together, we can make a significant impact.

Dream About the Future

One aspect that doesn't receive enough attention when it comes to living with a disability is the future. As a child, I was filled with anxiety about it and would avoid thinking about what my life might look like beyond high school. Questions like, "Could I get married? Have children? Find a job? Drive a car? Live independently?" haunted me. The future was a daunting concept, and nobody seemed to talk about it.

Even something as innocuous as being a bit stubborn, which can be a valuable trait when it fuels determination, often wasn't discussed openly. My parents, for example, would never say something like, "Katie, you're so stubborn; I hope we have six kids just like you." Or suggest that I meet someone because they use a wheelchair. It felt like discussions about the future were shrouded in silence.

Speaking of dating, it frustrates me when people tell me, "You'll find a special guy someday, but he's going to be special." This implies that it's somehow more challenging to love me because of my disability. My friends are incredible people, but they're not extraordinary just for being friends with me. In fact, they get good parking spots and may appear virtuous in public for being friends with me.

I once had a friend pick me up from the airport, and she simply grabbed my bag, threw it in her car, grabbed my wheelchair, and threw it in as well. We drove off, and she started laughing. I asked her why, and she said, "The guy at the curb just praised me for being such a great person because I'm friends with you." I couldn't help but retort, "You didn't even come inside to help me with my bag; what's going on?" She had barely paused the car to pick me up.

It's essential to break the stigma that society has attached to being friends with someone with a disability. It's not a special act; it's about genuine friendship, just like any other. Let's open up conversations about the future and challenge these misconceptions together.

Don't Lower the Bar

I'm often told that I'm an inspiration, and it tends to happen in unexpected places, like the grocery store—where most of my "inspirational" moments occur. One time, I was buying ice cream, taking advantage of a buy one get one free deal, when a guy approached me and placed his hand on my shoulder, saying, "You're such an inspiration." To be honest, I was a bit puzzled. My response was something like, "Well, you can get the same deal with your club card." It took me a moment to realize he was probably referring to the fact that I was buying ice cream while sitting down. But really, should that make me inspirational? It shouldn't. Yes, I have mobility challenges, but buying ice cream should not be considered an inspiring accomplishment.

What I consider genuinely impressive are things like climbing the Great Wall of China. There, with the help of friends who carried my wheelchair, I pulled myself up using the railing the entire way. Those are the kinds of feats that can be inspirational, but everyday tasks like buying groceries or getting dressed should not lower the bar for what we expect from people with disabilities. Let's raise our expectations and hold everyone to the same standards.

Find ways to connect with people, including your clients. Whether it's discussing sports, the latest movies, or even something like "The Bachelor," these shared interests can be bridges that bring people together. So, make the effort to find those points of connection.

Listen

Listening and truly understanding your clients is paramount. I once had an experience where I broke my leg and nobody believed me. After surgery and having the external fixator removed, I was a sophomore in high school, and I kept telling everyone that my leg wasn't healed, and I begged them to put me in a cast. It's not something you'd typically expect a 15-year-old to request. Unfortunately, no one listened, and I went home that night, inadvertently twisted my leg in my sheets while in bed, and re-broke my tibia. It led to another derotational osteotomy, and I was incredibly frustrated because nobody had paid attention to my concerns.

This story illustrates the importance of listening to your clients. While not every client will necessarily require exactly what they ask for, research shows that a strong doctor-patient relationship, which includes active listening and understanding, is a key factor in patient satisfaction.

Don't Underestimate Your Impact

I cannot stress enough the importance of recognizing your impact as a healthcare provider. Your role is absolutely crucial. Especially when working with individuals with disabilities or those who have experienced trauma, you have the privilege of entering a sacred and vulnerable space in someone's life. For many of your patients, it might be during the worst period they've ever faced. But for you, it could just be another routine day.

Take, for example, October 8, 2020, which happened to be a Thursday. It might have been just another day at the office for the anesthesiologist or a routine consultation with the psychiatrist who visited my room. However, for me, it was one of the most traumatic days of my life. My anesthesiologist had to perform CPR. The psychiatrist played a significant role in helping me maintain my mental stability throughout the ordeal. Then there's Wade, my physical therapist, who encouraged me to try out for the rowing team. Karen, my occupational therapist, visited me at home while I was in a halo brace. During those trying times, I had a couple of emotional breakdowns, and one of them was with her. I just felt seen and understood in those moments. There was Bill, who initiated my thyroidectomy, and Jake, who rushed in from down the hall to perform my emergency tracheotomy despite knowing nothing about me. The nurse and my doctor from Chicago also played pivotal roles in my recovery.

I have to mention Lauren, my nurse, who provided comfort during a particularly challenging moment. When I was wheeled back to the operating room for the third time and couldn't have a friend with me due to COVID restrictions, I started quietly crying. Lauren didn't say a word; she just reached out and held my hand. I'll never forget that moment because it was exactly what I needed, and she saw that without any words exchanged. It's a testament to the profound impact that healthcare providers like them can have in our lives during the most trying times. I also had two very supportive and encouraging SLPs who did my swallow study that cleared me to eat pudding again.

The Best Part

I wish people could see the positive side of having a disability. Sure, there's a lot of physical pain; I won't deny that. Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) has been physically traumatic for me, and I'm not trying to downplay it or minimize it. Being in a halo was a terrible experience. However, as I mentioned earlier, having my friends around, especially my best friend, made a huge difference. I remember one of my first days home with the halo, and I threw up all over myself while wearing the bulky vest. My best friend, who was my roommate, had gone out to run errands and said she'd be back in 20 minutes.

I couldn't wait, so I called her just five minutes after she left and said, "I just threw up all over myself." She rushed back home and lovingly cleaned me up. The look in her eyes is something I'll never forget. People often say their friends would do anything for them, and I've experienced that firsthand. These are the friends who flew across the country to be with me when I was in the halo. Being able to use my life and my experiences for something positive, something unique that others can't do because they haven't been through it, is incredibly rewarding.

I can encourage parents in other countries and let them know that their kids can go to school, too. Using my life as a gift to help others is the part about having a disability that often goes unnoticed. People tend to focus only on the challenges and the negatives.

The 82% of healthcare providers or physicians who believe my quality of life is subpar don't really get what I'm about. People often wonder how I ended up where I am today, and one vivid memory takes me back to my childhood. I can still picture our old dining room from back then. I was under the table, hiding from my sister because sharing a room with her was making me crazy. My mom had draped a long tablecloth over the dining table, creating a neat hideaway. I must have been around seven or eight years old, just lying there, taking it all in.

In that moment, I felt a wave of self-pity wash over me. Surprisingly, even at such a young age, I had a bit of an epiphany. Looking back, it's kind of funny, but I had a choice to make. I could either let my circumstances bring me down or use them to make my life better. And it wasn't just about having a positive attitude – I get it, that doesn't magically fix my bone density. But it does open my eyes to opportunities to help others and turn my disability into a force for good. Those opportunities wouldn't exist if I stayed stuck in the negativity.

One valuable gift you can offer your clients is to help them discover alternative ways to leverage their disabilities for positive outcomes. When working with kids, especially, it's crucial to provide them with hope. One of the most reassuring things I heard during my own challenging childhood was, "It gets better as you grow older." I clung to those words like a koala gripping a bamboo tree, even if it's a bit of an odd analogy. But it perfectly captures how tightly I held onto that hope. I thought to myself, "They said it's going to get better," and you know what? It did, and it continues to improve. I now enjoy truly incredible friendships and a fulfilling life.

Life will keep presenting its challenges. For instance, if I were to undergo another neck surgery or fusion, there's a good chance I'll lose my ability to drive, and that thought terrifies me. However, I've learned that I'll cross that bridge when I come to it, and I'll find a way to cope. It's essential, especially when working with kids or anyone facing adversity, to emphasize that things will improve. When people ask questions like, "Will I ever be able to drive again?" one comforting response can be, "We'll address that when the time comes."

Reflecting on my own experiences growing up, I recall asking my doctor whether I could accomplish certain things, and he never outright said yes or no. Instead, he consistently replied, "I don't see why not." Now, as a healthcare provider myself, I appreciate that response immensely. It avoids making unrealistic promises or causing unnecessary discouragement, yet it leaves individuals with a sense of hope and possibility.

Top 10 Reasons Why It's Awesome to Use a Wheelchair

To wrap up, I compiled a list of 10 reasons why using a wheelchair is pretty awesome. One undeniable perk is that my arms look ridiculously good - no Photoshop tricks involved; those pictures are the real deal. Then there are the parking privileges; they alone make it worthwhile. During the holidays, my friends seem to materialize out of thin air, always eager to accompany me to the mall. I can't help but suspect it's just for my parking pass, but hey, that's alright. I'll go along with it.

Once, I managed to sneak an entire tray of nachos into a movie theater - a feat that wouldn't be as smooth without my wheelchair. Another advantage is that I don't need to double-knot my shoes in the morning, granting me an extra four precious seconds of sleep. And let's not forget my built-in cup holder, a handy feature even when I'm not sporting my halo.

Additionally, I've been bumped up to first class on flights about three times. I figure, "I can walk on the plane if I'm seated in the first few rows, so why not put me in first class?" On one memorable occasion, I conquered Disneyland's Space Mountain six times within an hour - a thrill that never gets old. I find immense amusement in observing people's reactions when I ride escalators in my wheelchair. Plus, my wheelchair tires are more budget-friendly than buying new shoes, and the best part? I can wear just about any shoes I fancy, even those six-inch stilettos. My feet don't hurt! And, I am undefeated in musical chairs.

Summary

I'm not trying to downplay the fact that living with a disability can be tough. It's not a walk in the park. The most challenging aspects often revolve around social and environmental barriers. While the physical hurdles are significant, there are medications and adaptations that can help with those.

When I'm in pain, I have access to medication for relief. When I wanted to learn how to drive, I could adapt my car to make it possible. But what's really disheartening is how people sometimes perceive me because of my appearance, especially within healthcare settings. It can be demoralizing.

And then there are the environmental obstacles, whether it's in hospitals, healthcare facilities, or public bathrooms. Imagine going to a restaurant, having a few drinks, and then being told by the manager, "We've never had someone in a wheelchair need the bathroom before, so it's not a problem." Trust me, it's a problem for me.

I genuinely hope that all of you will take the time to learn the basics of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). This includes understanding restroom accessibility, the rights of people with disabilities when flying, and parking regulations. By advocating for accessible communities, you can help ensure that individuals with disabilities can navigate the real world with greater ease.

Remember, no matter how much progress we make within clinical settings, if we send people back into a world that's not accessible, we're not fully preparing them for the challenges they'll face. Accessibility should be a fundamental aspect of our communities, ensuring equal opportunities for everyone.

Citation

Sorensen, K. (2023). Disability inclusion: what healthcare providers need to know. SpeechPathology.com. Article 20621. Available at www.speechpathology.com