Introduction

This course is Part 1, which will cover the information on dentition. Part 2 (Course 8412) will focus more on mouth care. The impact of dentition, or sometimes the lack of dentition, is a very important consideration when assessing a patient’s ability to handle specific diets and food safely. Oftentimes, lawsuits that I deal with usually have a connection between the dentition and the diet the patient was on, as well as supervision, so we need to be very careful with these considerations.

There is a connection between dentition, hearing and perception of texture and taste, which often comes as a surprise to people. So all of these factors are connected when we're looking at how pleasurable mealtime is for our clients.

In this course, we are going to discuss the impact of aging on dentition, the connection between chewing and saliva, the impact of dentures/lack of dentition on chewing, and also the diet selection.

After this course, you should be able to describe changes that occur with aging that impact dentition and chewing abilities. You'll be able to describe challenges because of the lack of dentures, the lack of natural teeth and the impact of dentures in the elderly population. You will also be able to identify the impact of poor or no dentition in selecting diets.

If you haven't noticed, we are phasing out the National Dysphagia Diet, and moving into the International Dysphagia Diet Standardization Initiative. I suggest you familiarize yourself with those different diets, especially the bite size. When a patient dies from a choking incident, if there is an autopsy, they are going to measure the food that they take out of the airway. If that doesn't match up to your diet levels, we have some serious issues. So, we will talk about that framework.

Impact of Aging

Muscle Mass Changes

There are a lot of changes with muscle mass as we age, and one of the disorders that might be listed in a patient's chart is sarcopenia. This is the wasting away of the muscle fibers and muscles that are used, especially for chewing. Lingual sarcopenia is aging changes with the tongue. There is a loss of muscle mass and the tongue doesn't have the range of motion. So when we start seeing sarcopenia, it may actually be listed in the patient’s chart as a generalized weakness or deconditioning. This is, in fact, sarcopenia, but it just hasn’t been given that name.

The muscle fibers that are recruited for swallowing are muscle fiber type two. These are the really fast, explosive muscle fibers. We swallow and then the muscles rest for the next presentation of the bolus. When there is malnutrition, those muscles don't have the energy to move as effectively, efficiently, or as fast as they should.

There are many variables that come together which means that there are changes to a number of muscles. The masseter and the medial pterygoid muscles are typically the muscles that are affected with chewing, however the temporalis is worth mentioning as well. Those muscles work together for that up and down movement of chewing.

The density of the masseter and medial pterygoid muscles is also lost. There is about a 40% loss in density which causes a change in the bite force. That is something that should be recognized when doing evaluations. We need to take a look at not only the dentition but how strong or how weak that bite force is. A patient is not going to move off of a puree diet to a texture if their bite strength hasn’t been addressed. It would not be safe to move a patient up the food chain if the jaw force, bite force, how easy or how hard it is to break down food is not addressed.

As our patients age, they begin to complain about the food in the facility, “They didn't cook it. It's too tough.” They blame the food for their difficulties when actually it is the muscles. The food really hasn't changed in how difficult it is to chew, what's changed is their muscle strength. We see this in individuals who have dentures because there is a change in the muscle mass and a change in the strength of the chew when individuals have dentures rather than their natural teeth.

Elderly and Chewing

As we age, there is a decreased number of functional pairs of post-canine teeth which are the premolars and molars. Functional pairs, meaning, that the upper and lower teeth meet properly to break down food. The molars and premolars are actually the ones that break down the food. Again, with aging there is decreased strength for breaking down the bolus. If a patient doesn’t have those back teeth, they are then using teeth that are not meant for chewing. Teeth that are used for biting and cutting don’t have the strength for chewing.

The other thing that happens when we chew is that up and down movement in the jaw stimulates the parotid salivary gland to produce saliva needed to form a cohesive bolus. However, a prolonged chew can actually flood the bolus. There are a couple of reasons why a prolonged chew can occur. The patient may not have the strength to break down the bolus very quickly, so they keep chewing and that floods the bolus. According to the literature, the other reason a prolonged chew can occur is because the person can’t build up the pressure in the oral cavity to act as the plunging force. Regardless of the reason, the more you chew, the more saliva the parotid gland is secreting. So, instead of the saliva actually allowing the food to come together as a cohesive bolus, flooding occurs which increases the distance between the food particles causing fragments all over the oral cavity. That, in turn, can cause premature spillage or poor oral containment.

When assessing or observing patients, it’s important to look at the teeth. How many do they have? Are they missing any premolars or molars? If so, that will cause some additional problems.

If a patient is put on a thicker consistency, such as purees, that will require a lot more driving force of the tongue. A lot more tongue strength is needed and a stronger pharyngeal contraction is needed. Putting a patient on a thicker liquid can actually make it harder for them to swallow. Thinner purees can actually be better for our patients. Always consider the individual needs of the client. However, if the food is extremely pasty, many patients are going to have a problem swallowing it and that is a choking hazard.

Hearing

When we lose our sense of hearing and it becomes less acute, we know that there is increased difficulty hearing others speak. However, what was not realized until recently is that during the process of chewing, we're sending information in those sounds through bone conduction to the brain, and that helps to perceive texture. If you've ever worked with special-needs children, some of them are extremely sensitive whenever they are chewing certain foods because they can't stand the noise. They need to have the smooth, bland diet because the crunching is unbearable. But we need that crunch to perceive texture. When that information goes to the brain and we perceive that there's texture, the brain then sends information back down to the mouth, saying, "This is how you need to adjust the chew to deal with that texture." If a person has dentures, they’re not going to get that input or the information to adjust the chewing. That is why we see changes with dentures and why there is a coarser bolus.

Teeth

As we age, the surface of the teeth become much flatter. Older patients’ dentition is often very flat and worn down. Those teeth aren't going to be as effective with the chewing process. Also, as we age, we chew longer and use more chewing strokes. But despite chewing longer and chewing more, we still don't have chewing efficiency. Again, we're missing that strength.

In regards to swallowing, it is documented that food that is safe to swallow is about two millimeters in particle size - not bite size. There is a big difference. Particle size means the food is processed and it is the size that is found to be “swallow safe”. The International Dysphasia Diet Standardization often talk about a bite size of four millimeters or 15 millimeters. They are very, very specific about the bite size. Even a soft food will require multiple chewing cycles to produce a two-millimeter particle size.

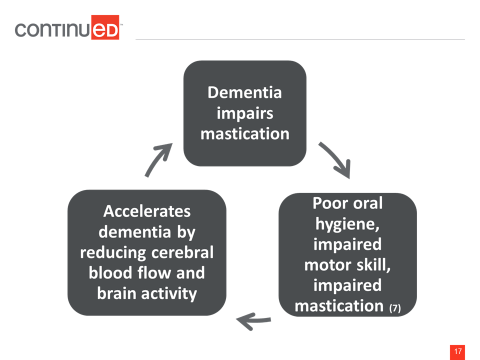

Dementia impacts a person’s ability to chew and many individuals with dementia have poor oral hygiene. Staff members are not very willing to do oral hygiene with these patients because they are concerned about being bitten. Individuals with dementia sometimes bite, even unintentionally, and it can be very painful. I can recall a nurse who got his thumb too close to a patient’s mouth and the patient actually bit the thumb off. So, a lot of the staff is very reluctant to do mouth care because of the risk to their fingers from the biting.

Reduced blood flow and brain activity accelerate dementia and when the downward spiral of dementia occurs, it is very difficult to slow it down. Once it starts, it just continues (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Dementia’s impact on oral health.

Saliva

Saliva changes as we age. The composition is different and the flow rate slows down. The different enzymes and the sodium and potassium levels change in saliva, especially if for those who are diabetic. In healthy, non-medicated individuals, by age 70 the average flow rate of saliva is almost half of an individual in their 30s. Again, this is not due to a disease process or medications. Saliva flow is reduced by half for the healthy individual.

Xerostomia is also present. Saliva is critical for forming a cohesive bolus. It helps to bind the food particles together. If saliva is not present, it is very difficult to process food. This is why we are often asking for extra sauces or extra gravy on the side to make the food moist. Xerostomia changes our sense of taste and the ability to keep dentures in place. One way that dentures are kept in place is that they suction on the bone, and saliva is needed for that to happen. If a person has dry mouth, they may end up with floppy teeth. Imagine what happens if a person with floppy teeth puts food in their mouth. They're not going to be able to control much of anything.

By adding disorders and medications to the mix, along with the aging factor, there are going to be a lot of changes with saliva. There are some medications that cause decreased production, and some that cause increased production in secretion. It will vary depending on the patient's medical history and medications.

The average person generates a large amount of saliva, more than ½ a liter per day. We are unconsciously swallowing saliva about once every minute, or every two minutes in the younger individual versus the older individual. So there is this routine of swallowing. If we have dry mouth, there's nothing to swallow, and that can actually impact the opening of the upper esophageal sphincter. When we swallow food, liquids and saliva, the UES opens and closes. We are using the UES and exercising it. If a patient has dry mouth, then they don't have saliva to swallow in between meals. Their swallowing is less frequent and that muscle can lose its elasticity.

Saliva Glands

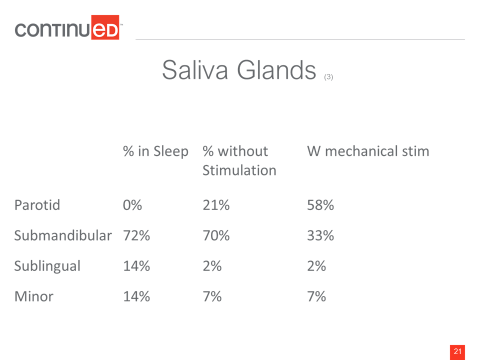

There are a number of glands that produce secretions. The percentages that each gland produces while sleeping, when there is no stimulation and with mechanical stimulation (i.e., chewing) are provided in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Percentage of secretions produced by saliva glands.

The parotid gland is the gland that secretes most of the saliva when chewing. It is activated by the up and down movement. So if we have a patient that has a diet with texture, we will see a lot of that up and down movement which then stimulates the saliva production from the parotids. During sleep, the submandibular gland is the one that's most productive and decreases the secretions when chewing. Sublingual and minor glands also contribute, but not as much as the parotid or the submandibular gland.

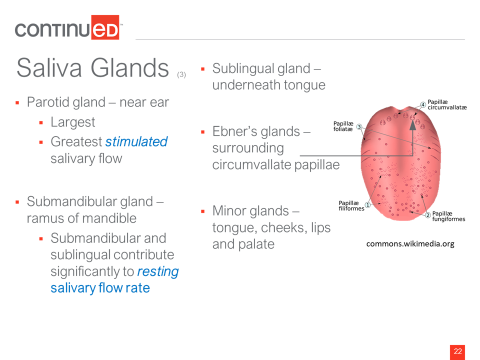

Looking at the glands, the parotid is near the ear and is the largest of the glands. It creates the greatest saliva flow when it's stimulated. The submandibular glands are located around the ramus of the mandible and contributes significantly to resting salivary flow rate. So there's no stimulation, this is just what happens during the day. The sublingual gland is under the tongue, and produces saliva as well. The submandibular and sublingual glands produce a viscous, or an elastic saliva that is thicker. The parotid gland secretes something that's much more watery.

There are Ebner’s glands on the tongue around the papilla and there are also minor glands located on the tongue, lips, cheeks and palate. The minor saliva glands are the tiny bumps that can be felt if you put your tongue in the anterior sulci between your bottom teeth and lower lip.

Figure 3. Location of Ebner’s glands and minor glands.

Types of Saliva

The parotid gland produces the watery saliva and the submandibular and sublingual glands produce the elastic or viscous saliva. That elastic saliva actually adheres to the surface of the mouth and protects the teeth from acid, such as the acid from certain foods or acid that is reflux coming up from a laryngopharyngeal reflux disease. Those secretions coat the teeth to protect the enamel surface. Saliva contains mucin, which gives the saliva that slimy characteristic. Mucin helps lubricate the food and helps form that cohesive bolus.

Highly elastic saliva is not moist and it is a very slow, spreading saliva. It doesn't flow very easily throughout the mouth. In comparison, the inelastic saliva that is produced by the parotid is basically watery and gives the perception of moistness.

Saliva Flow Rate and Viscoelasticity

Different beverages, chewing gum, and mint produce significant differences in the saliva flow and the elasticity. Therefore, what is consumed can create different types of saliva in the mouth. Acidic beverages stimulate the highly elastic saliva from the submandibular and the sublingual glands. It adheres to the surface so the acid can flow over the teeth and doesn’t damage them. Flavorless chewing gum, because of that up and down movement with the jaw, is going to stimulate the inelastic saliva from the parotid, which closely resembles water, and gives the sensation of moistness.

When chewing food, there is a “buffering effect” from saliva. So five minutes after you've consumed the food, there is a rise in the pH level and saliva/food are a bit more acidic. Then after about 15 minutes, the pH falls back down to about 6.1. The higher the pH number, the less acidic the saliva or the food is. That pH variation protects the oral tissues and teeth.