Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- List the causes and modifiable risk factors for dementia and the significant role of hearing loss in the equation.

- Describe the implications of the communication changes and behaviors that occur with dementia and their implications for speech-language pathologists.

- Describe the hearing interventions options that have proven successful for persons with dementia and hearing loss and criterion for use and referral.

Introduction

I want to introduce myself because many of you probably do not know me since I am an audiologist. I have been practicing audiology since 1976. I received my PhD from Columbia in 1980. My focus has always been on a public health perspective. I had considered a PhD in public health, but I chose to get one in audiology; however, the focus of my research and that of my collaborators is public health. My research is very clinical, and focuses on the individual patient and the role that hearing loss plays in successful interventions. My first study was on social isolation and hearing loss, and the second program of research I did in 1983 was on dementia and hearing loss. At the time, most people were not interested in these topics, but now they are exceedingly timely.

Demographics: Aging, Hearing Loss and Dementia in the 21st Century

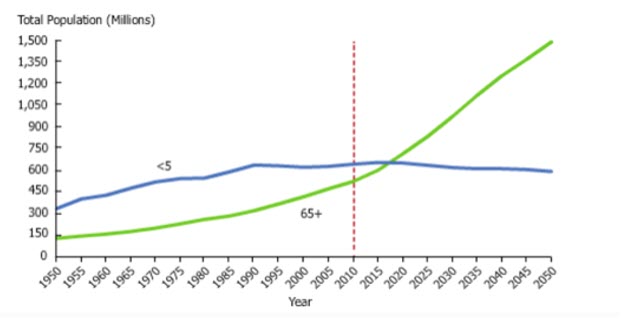

I first want to familiarize you with the demographics of aging. In Figure 1 - and I am sure it is no surprise - the number of individuals 65 years of age and older is on the rise, and the number of individuals under five is leveling off. We are facing a demographic revolution.

Figure 1. Demographic revolution.

Aging in the 21st Century

People who age in the 21st century differ from the people we started out working with when we were practicing 20, 30, or 40 years ago. Older adults are now healthier, they live longer, they are retiring later, they are socially and politically engaged, and they are dedicated to living purposeful lives.

Hearing Loss in the 21st Century

I will suggest that the ability to hear and communicate is critical to people as they age because social engagement is key to longevity. The rapid growth in the number of people who have hearing loss in the 21st century is profound, and this is attributable to the fact that most people are living longer. As they live longer, they suffer from chronic conditions. We have, presently, about 44 million people with hearing loss, and this number is expected to nearly double by 2061 when it is projected that there will be 74 million. It turns out that the number of adults with hearing loss will increase to the point that people are going to be living 30 to 40 years with mild to moderate hearing loss because of the longevity factor. Many of the patients that you are going to be working with are likely to have hearing loss. Most of the people that you will be working with will not have hearing aids, which is the primary solution for hearing loss.

Interestingly, hearing loss recently became the fourth leading cause of years living with a disability. It increased from the 11th leading cause in 2010 to the fourth leading cause in 2013 and 2015 because of all the studies that have been published showing the negative health outcomes associated with hearing loss. Hearing loss is associated with many risk factors. It increases the risk for falls. Hearing loss increases the risk for hospital readmissions. It increases the risk for shortened mortality. Therefore, hearing loss is a major chronic condition to which you should be paying attention.

Dementia in the 21st Century

Let's move on to the discussion of dementia. With the rapidly growing older population, there is a dramatic increase in the number of people diagnosed with dementia, such that presently about 50 million people are living with a dementia diagnosis. It is projected that by 2050, 152 million people will be diagnosed with dementia. Alzheimer's disease accounts for 60% to 80% of the dementia cases, so it is the primary cause of dementia.

Dementia, as I am sure you are well aware, is costly. Because there are about ten million new cases every year, the long-term medical and end-of-life care costs are tremendous. If global dementia care were a country, it would be the 18th largest economy in the world. The $818 billion spent on dementia is mostly due to costs related to primary care by family members. It is the seventh leading cause of mortality. It is a very significant condition, and it is obviously on the rise. The financial and social burdens are tremendous.

Dementia is the greatest global challenge for social and health care. What we know about hearing loss is that while it is a challenge, hearing loss intervention provides one of the greatest opportunities for early detection and prevention of the onset of dementia. We will talk more about that later.

More than 90% of people with dementia have hearing loss. Most persons with dementia and hearing loss do not use hearing aids. Dementia and hearing loss are both under-diagnosed in primary care; they are often diagnosed in later stages. We know that fitting hearing aids earlier may have a mitigating effect on the memory loss trajectory. So I highly recommend that you think about hearing status in the patients with whom you are working.

Scenario

Here is a typical person that you may run into: Mrs. S. works hard to follow what others are saying, especially in noisy environments, at parties, at office gatherings, or on the street. Her cognitive energies are focused so much on trying to understand what is said and trying to remember people's names that it is difficult for her to remember much of what is said. The conversation at parties with friends tends to go on, and within a couple of minutes, she has lost track of what is being discussed. She is guessing at responses, making noncommittal replies, and nodding her head as if she understands.

All of this happened to me yesterday with a friend of mine. Nobody knew that she could not understand one thing that anybody was saying, but she shook her head so it looked like she understood. When she walked away from her friends, she had no idea what was being discussed. Is this hearing loss? Is this dementia? Is this both?

Dementia Facts

What is dementia? Is it a disease? Is it a term synonymous with Alzheimer's disease? Is it an umbrella term for a group of symptoms involving cognitive deterioration? Is it a wastebasket term that is overused? All of these answers are right. It is a general term, and it is an umbrella term for a range of conditions that affect the brain. It is a group of symptoms affecting the ability to process thought. It affects memory, of course, as well as thinking, behavior and social activities - severely enough to interfere with daily living and independent living.

Some characteristics of dementia are that it is progressive, and it is gradual in onset and often overlooked. Communication is impaired, as you are well aware. People with dementia have difficulty performing activities of daily living. There is memory loss, impaired reasoning, and a decline in the ability to learn new information. Physicians say that when it is serious enough to affect at least two cognitive functions, such as memory, attention, thinking, or language, dementia has started showing its face.

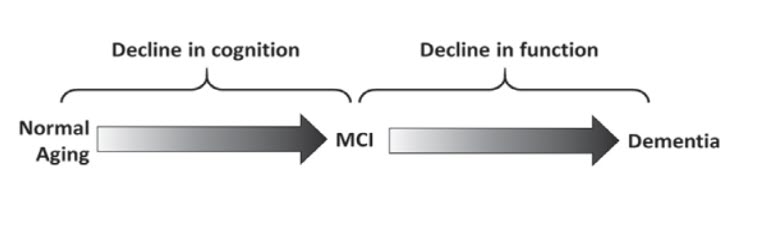

What is interesting about dementia is the decline and the trajectory. It is not a normal part of aging. With normal aging, there is a slight decline in cognition. Then as some people age, they develop mild cognitive impairment (MCI). A significant percentage of people with mild cognitive impairment progress on to dementia, and become unable to function independently and perform activities of daily living. So it is the decline in function that distinguishes between MCI and dementia - the inability to take care of oneself and to function independently (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Not a normal part of aging: the trajectory (Moga, et al., 2017).

Dementia is multi-factorial. It affects all regions of the brain and connections between the different regions of the brain. For example, the parietal lobe is affected, and so we have the communication difficulty; impairment in the frontal lobe leads to problems in judgment and executing basic tasks; impairment in the temporal lobe interferes with language, hearing, and recognition; and of course, the effect on the hippocampus interferes with new memory.

As I stated earlier, Alzheimer's is the major cause of dementia, accounting for about 60% to 80% of dementia cases. What distinguishes dementia, and what you should recognize about dementia, is that because it is a highly variable condition, it is under-detected in primary care. It is typically only detected at the later stages. The Gerontological Society and the Alzheimer's Society have developed a toolkit for helping primary care doctors recognize and identify dementia earlier.

There are individual differences in the amount of pathology required for the initial expression of clinical symptoms. This is very, very important: there are significant differences between individuals with regard to when the pathology expresses itself. Some people with neuropathological brain changes do not have dementia. We know that people who have good cognitive reserves can tolerate more neuropathology before they develop dementia. This is significant, and this is why it is very important to encourage your patients to remain engaged; engagement is protective against a decline in cognition. It is also important to make sure that your patients’ hearing is maximized because it is important for engagement and therefore is protective as well. Less cognitive reserve leads to earlier development of dementia. The reserve that people demonstrate may be related to the anatomical substrate of the brain, to cognitive adaptation, or to resilience; we are not sure, but there are a number of variables that influence this.

What is most interesting to me is that engagement in leisure activities really makes a difference in terms of onset of cognitive decline. If individuals participate in six or fewer leisure activities they are at greater risk for developing dementia, as compared to individuals who engage in more than six leisure activities. Engagement is very important because it contributes to cognitive activity, which strengthens the functioning and plasticity of neural circuits.

What we know now is that if an individual has hearing loss, he is not as active and not as engaged, and this is one of the possible reasons why hearing loss contributes to dementia. Make sure that you encourage your patients to remain engaged as much as they can.

Definitions of Dementia and Hearing Loss

Let's look at the definition of dementia and the definition of hearing loss. I have come up with my own definitions of dementia and hearing loss because I think that there is a lot of overlap. Dementia, as we have discussed, is a complex, multi-factorial process. It is a group of syndromes. Age-related hearing loss (ARHL) is an auditory, cognitive-based condition that interferes with communication, cognitive function, and performance of everyday activities. There is impaired processing of emotional prosody, impaired auditory encoding in the cochlea, and impaired decoding at the level of the brain. Because of the difficulty communicating and maintaining interpersonal relations, there is a tendency for people with hearing loss and people with dementia to disengage from social interaction.

Communication Deficit Trajectory

The communication deficit trajectory is interesting. We have a loss of memory, which impacts the ability to remember words and their meaning. There is increased difficulty using words to express needs and feelings, and understanding what others are saying. As people progress to a more advanced stage of dementia, there is an increased reliance on gestures and tonality when words fail. So, there is a need to communicate. The ability to communicate is impaired. However, the need and desire to communicate remains stable. What you have to do as a communication specialist is to find the best way in which individuals with dementia can communicate, and communicate with them using those methods. It turns out that using gestures can be an important mode of communication for people as they advance into later stages of dementia.

Hearing Loss and Dementia

Let's look at hearing loss and dementia, and how the two are related. You probably remember from audiology courses in graduate school that the ears help you to hear, but it is the brain that helps you to understand, use, interpret, and decode what it receives from the ears.

Which is it, Dementia or ARHL?

Try to visualize some of the patients that you see, and look at some of the overlap and the features that distinguish dementia from hearing loss. Both dementia and age-related hearing loss occur insidiously and frequently go unrecognized. Both are frequently attributed to aging. There is often a delayed recognition of dementia, and there is very much a delayed recognition of hearing loss. These delays are detrimental to the health outcomes that people experience. Earlier detection may improve patient outcomes.

There is a stigma associated with the diagnosis of dementia, and as you know, there is also a stigma associated with showing others that you have a hearing loss. This is why most of the people who wear hearing aids try to hide them. They do not want anybody to see them. I would argue that they should not hide the hearing aids because if people know that someone cannot hear, then they will modify their behavior.

General practitioners are often dismissive and not helpful in terms of diagnosing either hearing loss or dementia. General practitioners are not required to screen for hearing loss in asymptomatic individuals, and they are not required to screen for cognitive deficits either. What I mean by that is that the United States Preventive Services Task Force does not advocate screening for cognitive issues or for hearing loss.

Hearing loss and dementia are both a threat to safety, especially in the home. They are both associated with increased risk for falls. People with dementia are at greater risk for falls and people with hearing loss are at greater risk for falls. If you have dementia and hearing loss, that increases your fall risk significantly.

There is a cognitive reserve deficit in both cases, in terms of remembering, responding, analyzing, and thinking. It may surprise you that hearing loss is associated with memory loss. But when people are trying to concentrate on understanding what others are saying, they are using a lot of their cognitive reserve. They are bringing in the frontal lobe, especially, to help them decipher what is being said, and therefore they are not going to be able to put much information into memory. Sometimes, as I experienced yesterday, people with significant hearing loss may look and act like they understand but they walk away and have not really heard anything. Then they appear to misremember or not remember what was discussed.