Editor's Note: This text is a transcript of the course, Dementia Diaries Part 3: Evidence-Based Intervention, presented by Amber B. Heape, ClinScD, CCC-SLP, CDP, CMDCP

Learning Objectives

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Explain the challenges of evidence-based practice use in practicing clinicians.

- Describe how to evaluate evidence-based treatment approaches for patients with dementia.

- Describe how to compose daily documentation that supports the evidence-based skilled services provided.

Introduction

Thanks to everyone for joining me today. These next two courses, Part 3 and Part 4, I get really excited about. Of course, we need the background and the history of the different types of dementia and the different stages. That gives us our foundation. But this course goes into the evidence-based intervention component and as practicing clinicians, this is what we do day in and day out. So I get really excited about this content. Part 4 covers functional therapy activities and I get very excited about that as well. So I'm looking forward to what all we're going to learn today.

Should We Even Treat?

I've had this question posed to me before, very early in my career when cognitive-communication therapy or therapy for patients with a type of dementia, wasn't very widespread. So this is probably 15 years ago or so. A clinician that I respected very much asked me, "Why should you even treat a patient with dementia? They can't learn anything, they're gonna get worse anywhere." Fifteen years ago, I was a different clinician than I am now. I was newly out of a Masters program, and just in the skilled nursing setting full-time. So I wasn't really sure how to answer that question. But today, I would answer that question by saying, "Well, let's say that the patient is going out and they have something going on with their osteoarthritis. The patient comes back and they're not able to walk. Should physical therapy come in and treat the patient? Well yeah, that would be standard practice." If a patient comes into our facilities who's had a cognitive decline, then why should we sit back after that period of normal spontaneous recovery, and not intervene? My answer is we should absolutely intervene. People with dementia can learn new things.

Systematic Review of Existing Literature

Drs. Hopper and Bourgeois and their colleagues actually did a great systematic review a few years back. When they looked at all available researched evidence at that time regarding cognitive interventions for patients with dementia, they found that patients with mild to moderate dementia can learn new things. With moderate to severe dementia, there's less evidence to support individuals learning new things. However, we know that we can work on compensatory strategies. Memory techniques were very successful in facilitating recall. But the researchers also noted that therapy tasks should be functional. They also noted that sometimes specific global assessments don't show a huge improvement, but when we look at all functional areas and specific tasks for that patient, that's when we can actually demonstrate the benefit of our services.

What is EBP and Why Don’t More Clinicians Use It?

What is evidence-based practice, and why don't more clinicians use it? I'm going to be very transparent. 15 years ago, if you had said the word evidence-based practice, it would have struck fear in me. I thought that evidence-based practice was some unreachable term that researchers knew about but practicing clinicians really didn't have access to unless we wanted to spend all day every day reading research articles, which I wasn't comfortable doing. Well, my outlook has changed a lot which is why I pursued a Doctorate of Clinical Science. I wanted to be that go-between, between the academic researchers and practicing clinicians. It has become a true passion of mine to add to the evidence base but bringing it to a level that anyone who's practicing can understand what evidence-based practices are.

Evidence-Based Practice

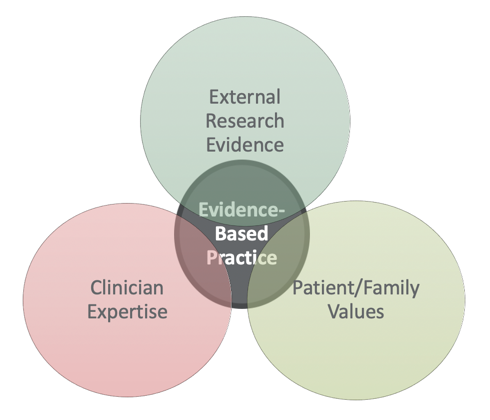

Evidence-based practice is a triad. It's not one single item, it's not just published research. External research evidence is one component of it. But, what is published as research may not be gold standard research or it may not be generalized to all the different populations. It may not be applicable to the specific population that we're addressing at any given point in time. That's why external research evidence is only one part of it. Plus, how would we ever find new treatments if we only depended upon that external research evidence? That's why evidence-based practice also looks at clinician expertise, as well as patient and family values. It is where those three components meet in the middle, that we have true evidence-based practice.

Figure 1. Evidence-based practice.

Why Don’t Clinicians Use EBP?

Douglas and colleagues did a study in 2014, on why clinicians did not use evidence-based practice. This really hit home with me because 10 or 15 years ago, I would have said the same thing. First, there's not a large amount of high quality double-blinded randomized control trials for every intervention. Those are the gold standard. However, there are so many minute factors and populations that we treat, that it's practically impossible to have perfect quality evidence out there for every single intervention with general visibility to all the different populations.

Also, there is not enough time to analyze or study what evidence exists. We lead very busy lives. We not only have our professional lives, but we have personal lives too. If you're working in healthcare, you have a nice little thing called "productivity" that drives your day in many instances. Just the time to search out that available research and then plow through it to see if it is good quality research or is it not? It's difficult to find the time for that.

Also, the inability or lack of knowledge in accessing evidence. Where do you find it? It's not just a Google search. And we know that research evidence that is peer-reviewed is much higher quality than just a website that says, "Hey, you should do this therapy." There is also inadequate training or a lack of confidence to apply evidence to practice.

But I have great news. ASHA has the ASHA Practice Portal. which is probably one of my favorite resources. If you go to the ASHA website, you can get to the ASHA Practice Portal. There are multiple full-time staff members at ASHA, whose only job is to access all of the available research that has been published in specific areas for diagnosis, intervention, et cetera, for all the different types of disorders or deficits that we see as SLPs. I encourage you to use this resource. It's part of what our ASHA dues pay for and it makes it very easy for us to access the evidence-base that's summarized for us.

Having No Intervention May Lead to Excess Disability

Another answer to the question of whether or not we should intervene at all is that having no intervention can cause that patient to have excess disability. That's a disability that we actually force on the resident because we do too much for them. If we have not fully assessed or intervened to see what strategies may work with that patient, then we don't have what we need to educate the staff on what the patient can do. That will lead to staff doing too much for the patient. That, in turn, causes staff to feel much busier, having less time to complete their duties and provide quality care or documentation. So, it's very important that when we intervene, we get the full picture. Caregiver education becomes part of our typical plan.

How Do I Begin Building a Cognitive Therapy Program

About 15 years ago, when I was just coming into skilled nursing, long-term care from a school system, I started noticing that there were patients who were having dementias because of infection and/or anesthesia-related decline. Patients were coming in with worsened cases of irreversible dementia after some type of medical comorbidity. When I started that therapy program, there had not been an SLP full-time in that facility. So it took a while for all of the staff to that I wasn't just talking to the patient. I was actually trying to make their jobs easier.

Once you find a core group of people who's willing to support and help in your cognitive therapy program, you will be surprised at how quickly that program becomes a vital part of your facility. The people who come in contact most with our patients are typically their CNAs or Certified Nursing Assistants. Anytime I've had students working with me, I tell then that a CNA has one of the lowest-paid, yet highest workload positions in the entire facility. They are the heart and soul of facilities. Nursing staff, therapy staff, social work, we're all a great part of that team. But therapy, and especially the CNAs staff, come into contact more and spend more time with the patient, compared to anyone else. So, get the CNAs to have some buy-in into your cognitive therapy program. Take the opportunity to celebrate Better Speech and Hearing Month having a quick little thank you get-together, where you actually tell them about the things that they can do to help your patients with dementia.

Evidence-Based Interventions for Patients with Dementia

In this course, we're going to discuss some of the evidence-based interventions for patients with dementia. I've picked the most applicable to adult healthcare that I see day in and day out which are:

- Cognitive Stimulation

- Validation Approach/Reality Orientation Approach

- External Memory Aids/Graphic and written cues

- Montessori-based interventions

- Memory training programs (spaced retrieval training)

- Caregiver training/counseling programs

- Computer-Assisted Cognitive Interventions (CACI’s)

- Environmental Modifications

- Reminiscence Therapy

Cognitive Stimulation

The first we'll discuss is cognitive stimulation and I've actually touched on this in the first two courses in the series. We know that 30 minutes a day, six or seven days a week of cognitive stimulation reduces that patient's speed of progression. The patients who had cognitive stimulation were about three times slower to progress into dementia. So like I have said previously, with early mild cognitive impairment, early dementia phases/stages, cognitive stimulation is something we need to teach the patient, and then have the patient be able to continue on their own, once they're off of our therapy caseload. It's not something that they do with us, and then they're done. Just as we tell students that they need to be life-long learners, our patients need to be life-long learners of knowing how to continue their cognitive strength as long as possible.

Cognitive stimulation not only improves function and wellbeing, but also quality of life. But there's not a lot of research that says this specific activity is best to do with patients.

Activities for Cognitive Stimulation. What types of activities could be included? You could do some memory training, use of mnemonic devices (e.g., "ROYGBIV", "Kings Play Cards On Faded Green Sheets"), those types of memory strategies, problem-solving. Anything that's multisensory - smell, taste, touch, sight, sound. Word games and puzzles are great for the patient to be able to do on their own. Social activities and using external memory aids are also great.

What is not beneficial for the patient is to do the same task over and over every single day. They're not activating those different parts of the brain when they do that. It's important that we talk with our patients, and say, "Hey, I know you love to do word searches. So if you want to do that five or 10 minutes a day, great. But we need to make sure you do some of these other activities as well." I know I've mentioned my mom on prior courses in this series and she loves Ruzzle on her laptop. She has one of the brain training apps, that's the free version. I tell her all the time, "Mom, you can't do the same task every single day. You need to mix it up." So some days, she plays Solitaire, some days she does Ruzzle, other days she does a word search, and other days she does crosswords. So, there are different things on different days that are going to work on different centers of the brain.

Reality Orientation Therapy vs. Validation Therapy

Our next two evidence-based practices are reality orientation and validation therapy. In my experience, reality orientation is really beneficial for those higher-level patients with mild cognitive impairment or early dementia. If a patient says, "Hey, today's Christmas," reality orientation would say, "Well actually, today's date is," and you give the accurate date. So we're actually re-orienting the patient to facts and to current events or surroundings.

Then we have validation therapy approach. The validation approach is really for those patients who are in mid to late stages where re-orienting them to the day of the week may not be the most beneficial, especially in those very late stages. If you want to see a great YouTube video, look at Naomi Feil and Gladys Wilson. It is a perfect representation of a validation approach. Naomi Feil, I think, is in her 90s now. She is a social worker, and she began this approach that really suggests that every behavior has meaning. Everything a patient does comes from feelings and their reality to them. So instead of negating that patient's feelings or reality, we validate what they're feeling, regardless of whether it's accurate or factual to us. We acknowledge that the statements they make have feelings behind them. We give positive words and gestures that give validation to that patient's feelings, and we use those to redirect the patient without that traditional reality-oriented redirection.

I was in a facility a few weeks ago and walked past a group of patients who were about to do some exercise. There was a lady sitting there sobbing uncontrollably. I put my hand on her shoulder because that's an example of positive touch - hand on her shoulder - and introduced myself. I said, "Why are you crying?" And she looked down on her lap and there was a baby doll on her lap. She said, "They're going to take my baby." Well, a reality orientation approach would have been to say, "That's just a baby doll. No one's going to take it, you're fine." Telling her that what she thought of as her baby was just a doll, in her late stages of dementia, is not going to be a positive experience. It canactually worsen problematic behaviors. So, what I said was, "Oh, that's your baby? What is her name?" She told me her name and I said, "Can I see her face? She is beautiful. Who does she look like?" And she said, "She looks like me." I said, "Well she is just beautiful. I can tell you love her very much, and you take such good care of her." She popped up with, "Well they can't take her." I said, "Oh no, we wouldn't want that. You take such good care for your baby. We know you love her. So let's just ask the nurse to look at her when she comes to give you your medicine, and that way, no one will need to take her." So we re-oriented her. She stopped crying and started rocking her baby. We actually sang to the baby a little bit and she was fine after that.

What was the logic behind that behavior? I don't know her life story. But I know that she was scared, she was insecure and possibly lonely. She needed someone to reassure her that it was all going to be okay. So that's what I did in that situation with the validation approach.

There is a small amount of research claiming that validation isn't useful. But there are many investigations, especially outside of the field of SLP, in the field of social work, that says it absolutely is useful. You'll find that with a lot of different evidence-based strategies, there will be an article somewhere that says it doesn't work. But then there may be nine that say yes it does. So we have to weigh our options and take everything with a grain of salt.

Validation Techniques. Here is a list of a few validation techniques that you can use. Of course, I've just told you about my recent experience and you look up Gladys Wilson and Naomi Feil, you'll see her use that genuine eye contact, physical touch, as well as observing and matching the patient's emotion.

- Listen with empathy

- Ask non-threatening questions

- Allow patient to maintain dignity

- Don’t negate everything the patient says

- Acknowledge feelings behind statements

- Reminiscence

- Paraphrase

- Use physical touch

- Use genuine eye contact

- Observe and match the emotion

- Use ambiguity if you don’t understand the meaning

External Memory Aids: Graphic and Written Cues

Next, we will discuss external memory aids. My favorite external memory aids are graphic and written cues. I had a patient come to me one day in tears. When I pressed her a little further to find out what was wrong, she said that she'd just gotten off the phone with her son and could not remember her grandchildren's names to ask about them. So what did we do? We made a family tree with all of the names of her children and grandchildren. I had to make a couple of phone calls and elicit their help. We made a graphic cueing system. where we drew and wrote on cardstock and laminated it. We put it in the top drawer of her bedside table and she learned that if she was on the phone with one of her children, she could pull out that graphic cue, and trace down and find the names of the children. Obviously, I don't have Alzheimer's. I've had family members who have it. But I can't imagine being a mother of two teenage daughters and all that that entails and one day not knowing their names. So, having something that could help preserve that would mean the world to me in that situation.

It's important to note that sometimes even in the later stages, reading can be preserved. So I've given you just a few examples here, of graphic and written cues, and external memory aids:

- Activity calendars

- Memo boards

- Memory books/memory wallets

- Appointment cards

- To-do lists

Montessori-based Interventions

Our next evidence-based practice is Montessori-based intervention. This is based on Maria Montessori who began her work in the early 1900s. I'm sure many of you have heard of Montessori schools before and we know that Montessori schools focus a lot on realistic practical learning. So when you think about Montessori-based interventions, that's what you think about: real-world, functional, meaningful activities. These activities can be individual or they can be presented in a therapy group. They should be appropriate, of course, to the patient's cognitive level.

Another big principle of a Montessori approach is breaking down a complex task. If, for example, there is a 6-step task, the patient may not be able to sequence six steps. So we break it down into two steps, and then the next two steps, and then the final two steps. This makes that complex task more simple. We also provide the cue and the guidance the patient needs to be successful. In Montessori interventions, the use of that functional, meaningful task really is based on the premise that muscle memory, things that the body is used to doing, like hanging up clothes on a clothesline or reaching into the cabinet for a can of soup, are things that people do throughout their lives. So, that muscle memory can actually be used to help patients with dementia in a Montessori-based setting.

Montessori Intervention Examples. Examples of Montessori-based intervention include meaningful items with familiar materials. We talked about the different stages in Part 2 and how certain stages need tactile stimulation. So, we may need to use actual objects for those patients. If the patients are in the very early stages, the may be able to use pictures or recipes. We have to categorize our materials into what may be beneficial for each stage of decline. We need to use materials that are easily recognized. In Part 4, I'm gonna give you a lot of activities that include occupational or hobby-based activities that can be very personalized for the patients. But the biggest takeaway that I want you to have from Montessori intervention, is that a functional therapy task is meaningful to the patient and can also be a positive indicator for quality of life.

Memory Training Programs

Next are memory training programs and the first is errorless learning. In errorless learning, the patient is taught only to respond correctly. We don't allow that patient to necessarily be incorrect. We immediately provide that prompt or cue for correctness, and then we decrease or remove those prompts once that patient can respond correctly on their own.

Vanishing cues is pretty similar, in that, as the patient becomes more comfortable with that learning, we reduce their reliance on our cues or our prompts.

Spaced retrieval is the final memory training program and it is my absolute favorite. Spaced retrieval training came about in the late 1980s. Some of you may not have been born then and some of you may have been out of high school then. I was in middle school in the late '80s. When this memory training technique came out it was a game-changer. There is so much data available that says spaced retrieval training is beneficial. I've even seen spaced retrieval successfully used to teach dysphagic compensatory strategies. It has also been used to teach specific information the patient needs about their health, et cetera. I've seen patients in my practice who could not remember 30 seconds during an evaluation, but with the use of spaced retrieval, they were able to remember those important facts for days on end.

The basic premise of spaced retrieval is, you give the patient a piece of information. It needs to be functional information and it should only be one fact or one group of facts at a time. You don't want to work on multiple different facts at the same time. It needs to be all related. It can be two or three steps, but it's one piece of major information that is used in a therapy session as you go through the spaced retrieval protocol.

So, you give the patient a piece of information, and then you ask the patient to systematically increase the amount of time that they are able to recall in response to a stimulus question that you will ask. An example of that could be that you have to wash your hands for 20 seconds with soap and water. Wash your hands for 20 seconds with soap and water. That is three small pieces of information that are all related to one. So, I would say that to the patient and then I would ask the patient, "What are you supposed to remember?" If the patient gets that right, then we double the time. We start at 30 seconds, we go to a minute, we go to two minutes. If at two minutes, the patient gets it wrong we go back down to the prior interval. That could look like, 30 seconds is correct, a minute is correct, two minutes is incorrect. So, we go back down to a minute. Another example - two minutes, correct. Four minutes, correct. Eight minutes, incorrect. What do we do? We go back to four minutes. We keep doubling that time interval every time the patient is successful in recalling that information. Then if they're unsuccessful, we back down.

Dr. Cameron Camp has done a lot of research with spaced retrieval. Jennifer Brush, Benigas and Bourgeois have done a lot of spaced retrieval research as well. Dr. Camp says is that once the spaced retrieval interval reaches 12 minutes, that information is actually transferred into the long-term memory. So, if we're going by that original protocol of 30 seconds, one minute, two minutes, four minutes, eight minutes, 16 minutes, once we get to that 16 minutes, we should be able to stop for the day. Then the next treatment session, we want to go back to see if they can still recall that piece of information that we trained yesterday - "Wash your hands for at least 20 seconds with soap and water." Using spaced retrieval, I've trained everything from the bingo schedule to a patient's doctors appointment, to hip precautions because the patient isn't supposed to lean forward during physical therapy, or locking the wheelchair brakes before sitting down. What are you supposed to do before you sit down? Lock your wheelchair brakes. There's a lot of different functional information. So, one of the best things you can do is ask the other therapy staff what you can do to assist a patient with learning a function task that they need to be able to do.

Caregiver Education/Training

There are several different caregiver education models. I kind of have preference for one but there are many different models out there. We know that when a caregiver is trained and educated, that there are more successful conversational exchanges with their loved one and they have improved quality of life. My favorite caregiver education is FOCUSED caregiver training which is designed to be used with family members of people with dementia as well as their caregivers.

The techniques of the FOCUSED program are:

- F - Functional and Face-to-face communication

- O - Orient to topic

- C - Continuity of Topic (should be concrete - no why?)

- U - Unstick communication blocks

- S - Structure the conversation with yes or no questions or choices

- E - Exchange conversation and encourage interaction

- D - Direct conversation - use short, simple sentences

When we're teaching staff to communicate, we can work with the CNAs, housekeeping, and the Activities Director, to really educate them on how to approach the patient so that when the housekeeper comes in, the patient doesn't think that, they are trying to steal her things when they go into her room. So, you bridge into that topic.

Teaching Staff to Communicate with the Nonverbal Patient

It's also crucial that we don't overlook the non-verbal patient. We want to teach staff that words aren't the only way that a patient can communicate. They can communicate through eye contact, facial expressions, body language, gesture, as well as touch. That reaffirming pat on the shoulder, the hand squeeze. If a patient's using hostile touch, what could that mean? We want to keep ourselves open to the fact that it's not just words that we have to look for.

In Part 3, I briefly talked about family counseling and how to ask the family certain questions in interviews. Another thing that I like to do with families is to explain why we're doing therapy and really involve them in the testing and the goal-making for their family member. Sometimes family members may just need to vent. So you just give them a chance to express how they're feeling, without rushing them along. Another thing you can do is ask the family, "What were some activities that your dad needed assistance with before coming here?" "What time of day did your mom typically eat her big meal of the day?" These are things that we need to know because they're part of that patient's normal routine.

As I said, I enjoy using that FOCUS caregiver education model to educate the families on the different types of communication modalities and the different information that I can get from questions, such as, "What was your father's appetite like?""What are your goals for your mom's rehab stay?" That's another great question to ask. Enlist those family members to be communication partners.

CACIs - Computer-Assisted Cognitive Interventions

CACIs include apps, computer programs, simulated reality tasks and are used to train patients to perform tasks of functional relevance. When I came out of graduate school, we were told to not use technology with older patients because they won't understand it. Those of you who work with older patients know that they all have cell phones just like we do.

There are interventions that do have some research, but it's really still emerging for what is most effective. If there's a brain training program that claims to prevent dementia, they're lying. Are there cognitive stimulation programs that are technology-based that could be used for stimulation? Yes, absolutely. There is a lot of technology being used right now as far as iPads, laptops and tablets, Surface Pros, etc, for our patients to communicate with their families, as well as in clinical practice and telepractice. But there are computer-esque programs, such as Never 2 Late, that are very good for patients with dementia, especially mild to moderate dementia. Also be sure that your patients with hearing and vision deficits are able to really see the screen or manipulate a touchscreen.

The research does suggest that CACIs are good for generalizing to real world tasks. But, specific global standardized test scores of cogniton, such as the GDS, may not change simply through the use of CACIs. What we have to look at are their different skills and abilities. If the patient can fix themselves a sandwich, and they couldn't before, that's a meaningful skill that the patient may need in order to go home. So, we can't lose focus on the specific skills and abilities.

Here are some examples of the programs that are available.

- It’s Never Too Late

- MULTITASK (large graphic library)

- BrainHQ

- Cognifit

- Brain Fitness Program

- Lumosity

- MindSparke

- Dakim Brain Fitness

- Happy Neuron

- Braingle

- Brain Age Concentration Training

- Queendom

- Elevate

- Peak

- Fit Brains

***These programs are examples and have not been verified***

I've not used all of them, I just listed some that are currently available. But be sure to do your own research to make sure that the program that you're using does have some functional research basis to it.

There are also many apps and I love using my iPad in therapy. You may have a different type of tablet, that's fine too.

- Tactus Therapy Solutions Apps (Free versions)

- Language Lite

- Visual Attn Lite

- SRT

- Category Lite

- Conversation Lite

- Scrabble

- Sodoku

- Memory!

- Just Say It!

- Sandwich Maker

- Unblock Me

- Ruzzle

- Brain Challenge HD

- Chain of Thought

- Fit Brains Trainer

- Word Warp

- Describe It

- déjà vu

- iMazing

- Conversation Starters- iTopics

- TherAppy Apps

- Story Creator

- MakeChange

- Answer Yes/No

- Text Twist

- Clockface Test

Tactus Therapy has a ton of really good apps and there are free versions. Tactus actually has a spaced retrieval training app, that keeps the time for you. You can actually put the information in, start the timer, and it will ding when that timeframe is up. I call it my Spaced Retrieval for Dummies app and I need that sometimes. You can also use different games that are online. I know people will say that you should never use a game with a patient. But my thought is that I'm an adult and I play games sometimes. We just need to make sure that the apps we use with our adult patients are adult-oriented. They're not something that's too childish.

Environmental Modifications

I've listed a few helpful hints for environmental modifications.

- Plants - make sure non-toxic

- Temperature - anticipate patient’s needs (they may not be able to tell you they are too cold or too hot)

- Hallways - med carts, linen carts, food carts should all be on one side of the hallway

- Color - use calming colors (not glossy, red, orange, etc.) Lavender, light blue, light green

- Homelike environment - fill walls with photos, memories, use quilts or bedspreads.

- Lighting - use soft lighting, drapes, blinds

- Toilet seat- other color that white

- Dining room - create homelike environment (tablecloths, contrasting placemats, soft music, china cabinet)

- Courtyard - wandering paths, benches to rest on, planters at different heights, bird feeders, secure environment

There are also some environmental things that should be avoided. For example, don't have wallpaper with small print. For someone who has a visual deficit, those tiny prints may look like bugs or roaches. Solid color walls are pretty good. My daughter used to get very upset at my mom's house because she had wallpaper with ivy on it. One of the pieces of ivy looked like a person's face to her. So, you have to be careful with the print on the walls. You need to avoid clutter. You need to avoid loud noises. Think about what type of loud noises we have. Bed alarms. When you're in school and the fire alarm goes off, what are you supposed to do? Get up, get out. Take cover, go away. Get from where you are. Sometimes those bed alarms sound like fire alarms. Could it trigger a memory that really actually increases the behavior? Of course. There are actually bed alarms that have voice prompts. You could have a family member program the alarm to say, "Dad, lay back down in bed and push your call button." Additionally, some hygiene products should be avoided because many could be poisonous.

Reminiscence Therapy

Reminiscence therapy uses all the different senses to evoke those positive memories in patients with dementia. It's used to decrease agitation and stress, and really establish a feeling of comfort and peace in patients with dementia.

How Do I Choose Which Approach to Use?

I get this question often. I kind of laugh when I say this, but they call it the practice of medicine for a reason. Even physicians don't always know exactly what treatment is going to benefit a patient the most, at that given time. We may think that a specific treatment is going to work with one patient, and it may not. As practitioners, we use our skilled judgment to determine if something is or isn't working. Maybe it's time I try a different approach. So the answer to this question really is that it depends on your patient. You just really have to know these approaches and be comfortable enough with them to have a good idea of the type of patient seems to do best with a given evidence-based approach.

Consider the Desired Outcomes When Choosing Therapy

We should always look at our desired outcomes when we're choosing goals for our patients. For example, let's say we have a patient on the GDS-5, where the patient can no longer live independently at home alone. Is that patient going to need medication management? No, the patient's not going back home so they're not going to need that medication management. That would not be a specific goal that we necessarily work on. If I have a patient who is a GDS-5, could I use money management? Some people would say no. But what if they want to get a drink or a snack out of the vending machine? What if they go out to the store with activities? Then, we may need to do more basic money management, counting out simple bills and coins, with that patient.

If someone is GDS-6, we may be working on following simple directions and answering simple questions. We're not going to be doing complex problem-solving with a patient who is a GDS-6. So really think about what we learned in Part 2, the different deficits in all of the different stages, and ask yourself if the goals you've set for this patient are appropriate for the anticipated discharge location, et cetera?

Documentation

Once you choose your approach, make your goals, and start your therapy, what do you do next? We all know - document. Documentation is something that I talk about day in and day out in my full-time job. I know I have said it over and over, but we must show the skill of our services. What makes the service we provide, complex to the point where it could not be done by any other professional? Why are we the ones who must give this service or this intervention?

Daily Notes Should…

We have to link those daily notes to our goals, and we have to show a progression. We can't do the same thing over and over and expect a different result. So I've given you some verbs here that are really just characterizing what we do, as therapists every single day.

- Analyzed

- Assessed

- Decision Making

- Demonstrated

- Developed

- Designed

- Educated

- Evaluated

- Facilitated

- Graded

- Incorporated

- Implemented

- Inhibited

- Instructed

- Modeled

- Progressed

- Provided

- Reviewed

- Selected

- Trained

Clinicians will ask if they can use the word "assess"? I tell them that we're assessing or grading performance every single treatment. If we're not, something's wrong. We may be designing a specific educational plan or a plan for stimulation. We may be evaluating that effectiveness. We may be modeling specific strategies for the patient. So use this list of words as you go through your skill in your documentation.

Daily Note Examples

The next few slides are examples of what daily notes for some of the different GDS levels may look like. You'll see that there is a complexity difference at each of these stages, that some of the evidence-based techniques that I use are used in multiple stages, and some are not. I want you to have some concrete examples of documentation for each of the stages.

GDS 2/3:

- Facilitated Montessori-based activity of executive functioning skills to improve patient’s ability to organize and self-administer medications properly at return home. Spaced Retrieval Training successful at 30 seconds, 1 minute, 2 minutes (x2). Patient struggled with memory skills over 2 minutes.

- Instructed patient in recall of safe transfer sequence with 7/7 acc and verbal cueing. Pt responded to safety questions regarding safe transfer sequence with accuracy in 3/4 trials(75%). Pt recalled walking sequence x 4 steps with difficulty recalling need to step first on weaker leg, right leg. Rehearsal technique used to improve recall of 4 steps in walking sequence with 4 rehearsals with errorless learning.

- Guided patient in completing sequencing pattern for transfer in 5/7 attempts with verbal cueing. Pt sequenced pattern for walking in 3/4 acc after multiple rehearsals and demonstration for improving comprehension. Pt recalled pattern with self-correction up to 5 min delay with 2/4 acc. Pt problem solved in structured task of Tangram completion with timely completion and mod assist necessary on 1/4 tasks, min assist provided on 3/4 tasks.

- Reinforced use of spaced retrieval strategy for increased recall of functional information. Pt recalled 4/4 functional information items at intervals of 30 seconds, 1 minute, 2 minutes, 4 minutes, 8 minutes, and to ¾ items at 16 minutes with min verbal cueing provided by SLP utilizing spaced retrieval strategy.

- ST graded recall of functional information in order to increase communication competence and safe integration within the environment. Pt demonstrated accuracy on 18/20 trials of functional information presented in lists of 5 items. ST assessed safety awareness and identification of potentially hazardous situations in order to increase safe interaction within the environment. Pt demonstrated accuracy of 10/10 trials independently of hazard recognition.

- ST graded recall of functional information in order to increase safe interaction within the environment. Pt demonstrated accuracy on 7 out of 10 trials given minimal verbal cues of information presented verbally with visual aid assistance. ST instructed patient and daughter on ways to maintain cognitive stimulation and activity when at home which includes, but is not limited to reading, word searches, crosswords ands puzzles. Daughter verbalized understanding and patient agreed to continue.

- Incorporated computer-assisted cognitive interventions to increase short-term recall skills. Instructed patient in use of personal device to increase cognitive stimulation upon discharge home this week. Patient demonstrated ability to access programs for intervention and ability to actively utilize 4/5 identified applications. Recommended 30 minutes of cognitive-stimulating activities per day upon discharge home (including computer-assisted interventions) in order to maintain gains made during plan of care.

GDS 4/5:

- ST facilitated delayed recall of novel information in order to increase safe interaction within the environment. Pt demonstrated accuracy on 7/10 trials given moderate verbal cues of ST selected items. ST graded 3 step sequencing of cognitive tasks in order to increase safe interaction within the environment. Pt demonstrated accuracy on 4/5 trials given minimal verbal cues for sorting and sequencing of 3 step ADL activities.

- Instructed patient in completion of Montessori-based task for sequencing ADLs. Chunking strategy used to maximize patient success. Computer-Assisted cognitive intervention task presented for patient word-finding skills. Patient presents with 15/20 correct, which is an improvement from the 10/20 correct last recording period.

- Skilled treatment provided bedside with patient oriented to person, roommate (by name), and confused to location/situation. Pt reoriented easily with visual/written cues. Pt reviewed information related to orientation to place/situation, and safety in personal room, then responded to wh- questions with 4/9 acc (44%). Rehearsal and rephrasing used to relay info regarding use of call button in a variety of situations; pt verbalized understanding. Pt demonstrated use of the button, and CNA responded in role play situation x1 rehearsal. Pt verbalized understanding.

- Pt oriented via written cues and responded to orientation questions without success. Pt difficult to redirect from environmental distractions this day. Pt problem solving during daily task of meal setup, with increased cueing necessary for scanning immediate environment for cues, and obtaining assistance from staff. Staff education initiated with x 2 CNA regarding need to consistently orient pt to call light, leave it in plain view d/t memory difficulty; verbalized understanding. Staff verbalizes that pt has not used the call light. Repeated role playing with CNA staff to model response to call light with pt demonstrating use of button.

- ST educated pt on safety instruments within the facility in order to increase level of safety and decrease risk of fall. Pt verbalized understanding and demonstrated use of call light. ST instructed pt on compensatory strategies to improve recall which includes but is not limited to chunking, lists and categorizations. Pt verbalized understanding of recall of compensatory strategies. ST graded recall of functional information in order to increase safe interaction within the environment. Pt demonstrated recall of 3/5 items independently but improved to 5/5 given moderate semantic cues.

- Instructed Pt in strategies for increased sequencing skills to facilitate increased participation and safety during ADL completion. Pt utilized problem solving skills to completed 4 step sequencing tasks using ADL pictures with 4/10 trials with mod verbal and visual cueing provided by SLP.

GDS 6:

- Developed graphic cues for patient due to perseveration of “where am I?” Patient was able to utilize graphic cue in 2/5 attempts. Errorless learning approach utilized to redirect patient in simple communication tasks with staff. Instructed CNA staff on effective communication with patient: i.e. using short sentences, yes/no questions instead of open-ended ones. Staff verbalize compliance.

- Guided pt in completion of convergent naming task with 0/6 acc; max cueing. Oriented x 1, difficulty with facility orientation. Pt responded to wh- questions regarding wants/needs in 3/6 attempts

- Patient seen in am for skilled speech therapy services. Treatment focused on verbal expression at the word level. Training provided for use of open -ended phrase and sentence completion to produce accurate words. Patient able to imitate correct words; however, unable to spontaneously generate words. Poor comprehension and inaccurate word responses.

- Patient sitting up in geri-chair. Treatment focused on verbal expression training to improve ability to express wants and needs and to communicate effectively. Names of objects modeled for the patient with patient able to imitate ¼ trials. Unable to spontaneously produce name of words. Auditory comprehension tasks addressed identification of objects in a field of 2 yet 0% accuracy. During treatment patient noted to have marked difference in cognition. Vitals taken with O2 saturation at 88% on 2L of oxygen and heart rate at 114. Therapy discontinued and patient care transferred to nursing.

- Facilitated bedside treatment, with patient presenting with increased alertness. Patient presented with eye contact, followed visual stimuli of "yes" and"no" cards in 4/10 attempts using eye gaze. Patient used head nods, "yes" in 5/10 attempts given visual and verbal cues and "no" in 2/10 attempts given verbal, visual and tactile cues to respond to questions related to things within his visual field, orientation to environment, pain and body temperature.

GDS 7:

- Assessed patient’s nonverbal communication of wants/needs and pain. CNA present for the assessment and provided input on patient’s usual patterns. Patient judged to grimace when in pain, and grasps nearby objects or people when she is in need of something. Attempted use of communication board for hungry, thirsty, and bathroom scenarios. Patient was resistive today, so strategy will be attempted again tomorrow. Patient reacted positively to music stimuli, and calmed when instrumental music was provided.

In Part 4, we're going to discuss the therapy tasks and activities that we can do as a clinician, and we will bring in that skill documentation to describe those activities and/or tasks.

Questions & Answers

When you have an interval with spaced retrieval, are you silent or do you do some other types of tasks, sort of as a distraction? What do you do during the times in between when you're checking their recall?

I don't throw a bunch of other verbal information at the patient. I may have them work on some type of activity that they enjoy. I've had patients who liked doing puzzles or crafty-type tasks. So they may do that while we're in between intervals. I've also had patients who were doing the exercise bike for another discipline. Well, they can exercise between our intervals. So I don't just sit there and look at them. That would be very awkward. They don't want to look at my face for that long either. But what I don't do is throw a bunch of language at them during that time.

I do spaced retrieval with patients - I work from home. I only see patients about one to three times a week. Is that too low of a frequency to work on spaced retrieval? Some of the research I've read about spaced retrieval is based on at least five times per week frequency of therapy.

The beauty of this is, if you have patients at home and they have a communication partner, or a family member that's able to assist, you may be able to train that family member to do some home practice. If your client has the app, then you could actually put the prompt into the app. It will allow you to type in that information and the patient could do at-home practice as well. So that would be a way you can kind of get those extra attempts in.

What is the difference between errorless learning and vanishing cues?

Functionally, there's not a ton of difference. In errorless learning, they're not allowed to make errors. In vanishing cues, they may be allowed to make some errors but you're just pulling the cues back. But functionally, they're extremely similar.

If you are filling those spaced retrieval intervals with tasks like crafts or exercise, then how do you document that? Can you be assessing some type of measures of social engagement or responsiveness during those types of activities? How do you account for that time?

You could have them participating in some type of pragmatic activity. They could be doing a sequencing task or a problem-solving task during those time intervals. That would still be therapeutic. As I said, I just wouldn't fill the time with a lot of either written or spoken language because too many words can get jumbled up.

Do you have any specific recommendations for some of the cognitive stimulation computer programs or any recommendations for higher-level patients? I've heard of Lumosity, and Elevate and BrainHQ. Do you know of any resources that might help me evaluate the differences between them and the pros and cons of each one?

I've done It's Never 2 Late, BrainHQ, and Lumosity. Those are the three that I've had experience with before. But that's not to say that those are better because of that.

Citation

Heape, A. (2020). 20Q: Dementia Diaries Part 3: Evidence-Based Intervention. SpeechPathology.com, Article 20405. Available from www.speechpathology.com