Editor’s Note: This text is a transcript of the course, Dementia Diaries Part 2: Staging on the Severity Continuum, presented by Amber Heape, ClinScD, CCC-SLP, CDP, CMDCP.

Learning Outcomes

- Describe the qualities of each of 7 levels of global deterioration.

- Identify characteristics of standardized and non-standardized assessment in order to accurately determine appropriateness for use with patients.

- Describe how to accurately capture patient characteristics and deficits in their documentation

Introduction

This is Part 2 and, in this course, we are going to get into the severities of dementia. In Part 1, we discussed the different types of dementia and we briefly mentioned that Alzheimer's has a number of severity levels. But we're really going to get into that in this course.

Why should we use dementia staging? Well, it is our roadmap for how we should treat a patient. It allows us to know what deficits the patient has because each stage of decline has a set of characteristics that is pretty unique to that stage. There is some overlap but when we stage a patient in that dementia severity scale or Global Deterioration Scale, it allows us train staff in how to best communicate with patients. It gives us a roadmap for what evidence-based strategies and practice techniques that we should use. It also helps us reduce excess disability. Excess disability is where we, as health care practitioners - whether that's therapy, nursing, CNAs - where we do too much for the patient. We don't allow the patient to do everything that he or she can do for himself or herself. Therefore, we are disabling the patient more than what the patient really is. That is what excess disability is and if you've been in a setting working with aging patients very long, you know that dignity is a very huge issue. We want our patients to be able to retain their dignity, their sense of self-worth. Placing excess disability on our patients by not allowing them to do everything they can do for themselves is very harmful to our patients.

Staging also allows us to focus on abilities, what abilities are intact, and how we can use those intact abilities to compensate for any deficits that may be there. We are maximizing function.

Normal or Abnormal?

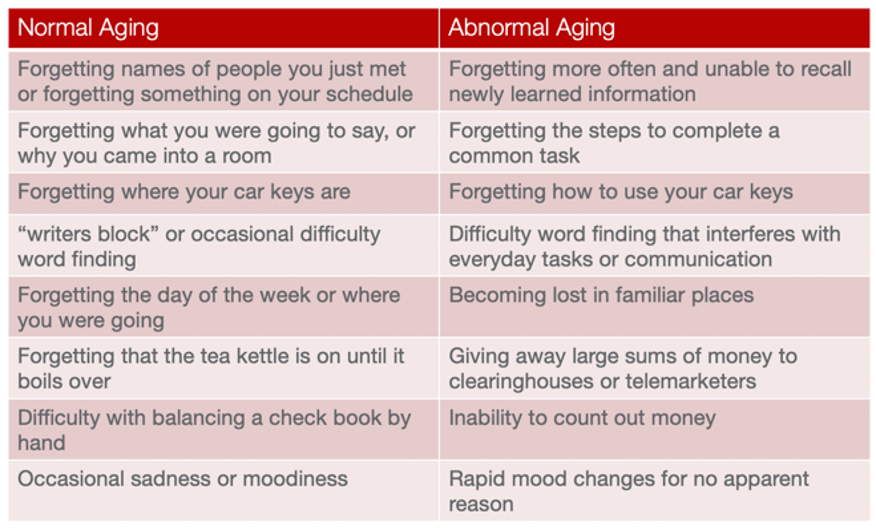

Figure 1 is a brief visual of normal versus abnormal.

Figure 1. Normal versus abnormal aging.

I want this course environment to be one that is very comfortable, that you enjoy learning, that you can take something away with you to put into practice tomorrow. Therefore, I'm going to keep the terminology pretty basic. So, one of the big things that I like to say when people say, "Well, you know, I'm forgetting where my car keys are. Does that mean I have dementia?” I say to them, “Well, no, forgetting where your car keys are does not mean you have dementia. If it did, I'd be in really big trouble. And if forgetting where your phone is meant you had dementia, then I've had dementia for years now.” Some of you may be the same. I have to use my Find My Phone feature all the time. But forgetting where your phone is or where your car keys are does not mean you have dementia. However, forgetting how to use your car keys or how to use your phone may indicate that something abnormal is going on neurologically.

As you talk to your patients and their families, they may have lots of questions about what is normal versus what is not normal. I encourage you to print this table and use it when you're providing that education. Hopefully it will be beneficial to you.

Where Does the Patient Fall on the Severity Continuum?

The question we should always ask ourselves is, “Where does the patient fall on the severity continuum?” There are seven major stages and there are different variations within each stage. So, it's very important that we accurately stage the patient.

Global Deterioration Scale

I've talked about the Global Deterioration Scale (GDS), and have referenced it a few times already. Dr. Barry Reisberg actually developed the GDS and you can get a copy of the GDS for free at: http://www.fhca.org/members/qi/clinadmin/global.pdf.

Stage 1 and early Stage 2 are normal. Middle to later Stage 2 and Stage 3 are what we would consider mild cognitive impairment or pre-dementia. It's not until you get to Stage 4 where you actually have a verified, diagnosed dementia. When I say “diagnosed dementia” take that with a grain of salt as well because we may see patients that we very well know probably have dementia. But if you remember from Part 1, we, as SLPs, are not the ones to actually make that diagnosis.

So, while the Global Deterioration Scale does reference the word dementia, I like to also think of it as decline: diagnosed major cognitive, neurocognitive disorder or decline. Here are these seven stages and we will talk about each of these stages momentarily.

7 Stages:

- GDS 1- Normal adult

- GDS 2- Forgetfulness

- GDS 3- Early Confusional State (MCI)

- GDS 4- Late Confusional State (Mild Dementia)

- GDS 5- Moderate Dementia

- GDS 6- Severe Dementia

- GDS 7- Late/Severe Dementia

As we go through each of the stages, we're going to talk about some of the neurological hallmarks of each stage. We're going to talk about some of the behavioral characteristics of each stage, as well as some of the physical and emotional symptoms that we may see.

Within each stage, there are decimal points. These are the mini-stages within a stage that I mentioned earlier. For example, when you are using an assessment such as the Brief Cognitive Rating Scale to stage a patient on the GDS, you may come up with a number of 2.8. That number is still in that GDS 2 range. But we have to look and say, okay, what is it closer to? A GDS 2.8 and a GDS 3.2 are going to be pretty similar. A GDS 3.2 and 2.8 are going to be way more similar than a GDS 2.0 and a GDS 2.8. So, understand that there is some fluidity here.

GDS Level 1 - Normal

Our first stage is GDS Level 1. This is you and me on a good day where we've had a great night's sleep. We haven't been socially isolated. We're functioning at our full potential. There really are no cognitive changes that are evident.

Our brain is a normal, healthy weight. There is some variation, but give or take a little, the human brain weighs right around three pounds. So our normal aging brain is around three pounds. It's functioning normally. Our neurons are firing just like they should be.

GDS Level 2 - Forgetfulness

GDS Level 2 is some mild forgetfulness. I like to say that GDS Level 2 is me on a day where I didn't get enough sleep. Things like fatigue, insomnia, being exceptionally busy, or having your mind worrying about a lot of different things, can give us cognitive functioning that really is in that GDS 2 range. This is where we forget things, where we misplace our phone and can't remember where we put it.

It's important to note that in those very earliest GDS 2 times, we really want to strengthen and stimulate our brain. As we go through Levels 2 and on, you'll notice that I have an age equivalency listed. When you look at each age equivalency, understand that we are dealing with adults and we should treat our patients like adults. Just because an age equivalency cognitively could be equivalent to a child in some cases, we don't want to treat an adult like they are a child. I give you those age equivalencies so that you can think of what normal people are; some of those characteristics that that age group may have.

When you think of a 25+ year-old, this is the age of most of my graduate students. Are they rather impulsive at times? Sometimes. If they make a mistake, they recover pretty quickly. They self-correct. Their visual acuity is normal. They may misplace their favorite T-shirt for a while or forget that they put it in the dryer. But overall, they are highly functional. They like to socialize. They're out spending time with their friends.

When you look at a cognitive examination, you don't really see major deficits unless you get into very complex testing. Adults at a GDS Level 2 can be self-directed learners. They can be given something, take it home, and work on it themselves.

Cognitive stimulation, which is an evidence-based approach that we'll talk about later on in the series, is ideal for GDS Level 2. Sometimes I am asked when to start treating a patient but there is no hard-and-fast rule for that. I've had patients who were a 2.8, who were reporting having some difficulties that were affecting their safety and their ability to live independently, that was a new onset, and typically a reversible cause that didn't spontaneously recover. I've treated patients at the late Stage 2. That's not to say that every patient who comes in at that stage I treat. You really have to use a multifaceted approach to determine whether treatment may be effective or not.

GDS 2 - Therapy Focus. If you do work with those late GDS 2s, then we want to teach them how to:

- focus during complex tasks

- have appropriate divided attention (which I'm admittedly, struggle with at times myself)

- use some brain training-type programs, apps on their devices

- practice cognitively stimulating activities

These are things you teach the patient how to do, and then treatment is done. GDS Level 2 patients are not those who are going to have a four-week plan of care. That's not appropriate. They may only have a few sessions for you to train them on how to maintain their cognitive function. Remember, Part 1, we talked about 30 minutes a day, six to seven days a week. Those patients are three times slower to progress into a dementia. So that's where my therapy with a GDS Level 2 patient is going to focus.

GDS 3 - Early Confusional State (MCI)

Next we're going to talk about mild cognitive impairment, or mild neurocognitive disorder, GDS 3. As I think we briefly touched on in Part 1, GDS 3 is kind of like the top of the hill and your patient could go either way. About 50% of people who have mild cognitive impairment will eventually progress into dementia. It is a progressive impairment. That's not always the case, though, especially for those with reversible causes. They may be able to recoup those skills. So that's one of those opportunities that allows you to get in there, do some quick, intense therapy, and hopefully mitigate that patient's likelihood of falling over that hill into decline.

As we look at GDS Level 3, think of an age equivalency of teens to 20s. We all know people in this age group. What happens with people in their teens to 20s? Heaven help me, I'm the mom of two teenagers, one of them is now driving. I think about my GDS Level 3 patients with their cognitive skills with things like, are they a little impaired sometimes in their judgment? Do they jump too quickly without thinking first? Are they sometimes irresponsible with their finances? Did they take their medications like they're supposed to? Or do they just decide, hey, I don't feel like it right now?

You'll also see difficulty when you present new or complex situations. Depending on patient personality, that can really go either way. For example, you can have some patients who really try to mask their deficits. Others will get extremely frustrated and just quit when they have a challenging task.

People in a GDS Level 3 work well with structure. They work well with routines and when you throw their routines off, that's when they struggle. People on GDS 3 also are, often very humorous. I think that is because it’s an ability to make people laugh and make people forget to focus on the fact that, the person really didn't understand that as much as she probably should have.

GDS 3 – Therapy Focus. You have to use the right assessments with a GDS 3. Some assessments are not going to be beneficial for a GDS 3 because they're really not sensitive to the types of skills and deficits that you're going to have in this stage. When you look at neuro hallmarks, you have very left-brain tissue loss at this stage. You're not really going to see any really quantifiable loss there.

This stage can last one year. It can last four years. I've seen this stage last much longer than that. It's one of the longer stages of decline. But many times, our patients who are GDS Level 3 don't have a dementia diagnosis. Those diagnoses aren't given until the patient's further down the staging process.

What's important to do with your patients who are at a stage 3 is ask their family members very pointed questions. Don't necessarily use the word dementia. Say, "Are you concerned that mom might not be taking her medicine like she should?" Or, "Have you noticed Mom doing things like turning the oven on and forgetting to turn it off?" Those types of questions really give you a lot of information on what was going on at home, whereas if you walk in and say, "Hey, have you been seeing any cognitive issues in your mother,” they're going to say no. You have to be very pointed and very specific in your questions. Once you do that, families become very, very open to that dialogue.

I've had to tell patients and families before, “Here is what we know about this stage. I'm not saying you have dementia. I'm saying you have some early thinking problems. But those problems may get better. But for some people, those problems may get worse. We want to use some strategies that are going to, hopefully, help prevent these difficulties you're having from getting any worse.”

At a GDS Level 3, a person can still live at home alone, but you're going to see people forgetting a lot of names, especially in a new environment. If you're in a residential care environment and your patient is meeting a lot of new people, you may need to use some memory/learning strategies, such as spaced retrieval or strategies like chunking, to help that patient learn new information.

At a GDS Level 3, these patients are still absolutely capable of learning new information and thriving. It just may take a little longer than usual. They may have a little more difficulty getting there than they would have a few years ago. So, it's very important with a GDS Level 3 that you do not give patients anything that's very childish-looking. That will offend them. You need to focus on those higher functioning tasks like medication management, numerical reasoning, money management. We'll talk about some functional therapy ideas in Part 4 in this series. But you really want to focus on where the deficit is and make it meaningful.

GDS Level 4 - Late Confusional (Mild Dementia)

GDS Level 4 is also known as late confusional state. You may hear a term “posterior cortical atrophy” or PCA and that is related to vision impairments that happen as dementia occurs over time. With a patient who is GDS Level 4, who's that very early stage of dementia, their visual field is going to be about 12-24 inches. So, for be sure to have therapeutic intervention occurring within about two feet of them if it's any type of manipulative or print or things like that. Because they are starting to have some visual field deficits, or some atrophy.

At this stage, there is about four ounces of brain tissue loss which is about a ¼ of a pound. That’s about an 8% loss of brain tissue. If you think about taking about 8% of the function away, you’re going to start seeing deficits.

The age equivalency for GDS Level 4 is eight to 12 years. So, think of someone who is in those late elementary to middle school years, what happens? Sometimes they withdraw from challenging situations. They thrive well in routines. When you take away the routines, they are discombobulated and frustrated. They don't perform as well when those routines are gone.

This is the stage where I like to say they talk the talk, but they can't walk the walk. People are noticing that they're having trouble. Family is starting to say, "Hmm, something's going on here. I'm not sure, but something's off." You're going to see attention impairment. You're going to see early dysfunction of taste and smell. You may see some depression in patients as they become aware of their deficits. They may withdraw from some activities or hobbies that were their favorite. I've known patients who were avid crossword puzzle completers, and in this phase, their family's like, "Oh, he said he doesn't like crossword puzzles anymore." Well, it really wasn't that he didn't like them. It was that they'd become too challenging for him.

You will also see patients who are out in the community starting to have questionable decisions about finances or questionable abilities to use money, handing the wrong amounts of money, the wrong change, and really struggling to balance their checkbooks. I had a family member who, in this stage, had never bounced a check in her life and all of a sudden did. That was one of the very early signs that something was going on. You may also see amnesia, aphasia, agnosia, and apraxia start in this GDS Level 4. Word-finding abilities are absolutely going to become a little more difficult here.

Their ability to find their way around a facility or an area is becoming more difficult. If they're still driving they might get lost on a route that should be very familiar to them, but all of a sudden they're getting turned around and getting lost. You also may see patients in this phase start isolating themselves socially. You may see differences in how they perform their job, if they're still working. Because remember, you don't have to be older to have dementia. It does affect younger people sometimes.

At a GDS Level 4, these people are still able to live alone. But they may need assistance with the more complex items that are day-to-day tasks. When you think of an eight to 12-year-old, a 12-year-old could stay by themselves for a little while, but we're definitely not going to hand them the checkbook and say, "Hey, go get groceries." That's probably a little beyond their cognitive abilities.

GDS Level 4 - Therapy Focus. What should we focus on in therapy with a GDS Level 4? We can focus on graphic and written cues using list or visual organizers. Montessori approaches and spaced retrieval are great with GDS Level 4, and we'll talk about those later in the series.

Our therapy needs to be functional. It needs to be task-orientated. It needs to be activities and items that are going to help the patient be as independent as possible. This level of decline alone is not going to cause the patient to need long-term care or even necessarily assisted living. So, we need them to be as functional as possible out in the community.

GDS Level 5 - Moderate Dementia

At this level, you have anywhere from a half-pound to a pound of brain tissue loss. That's almost a third! We're going to see major issues in patients at a GDS Level 5. This stage doesn't last as long as Stages 3 and 4. It's a shorter stage, typically about one to three years.

Age equivalency for GDS Level 5 is around four to eight years old. I don't know how many of you have four- to eight-year-olds, but think of how much assistance they need. Could they live alone or stay alone for any amount of time? No, they can't. This is the stage in which the patient now requires some type of long-term. They can no longer live at home alone. When you think of a kindergartner, how do they learn? They go to centers. They have lots of manipulatives. They learn by doing. Tactile stimulation is very important at a GDS Level 5.

You're not going to want to plan a 60-90 minute therapy task. You will lose their attention or you're going to spend most of that time redirecting them. Tasks are going to need to be broken down into smaller components.

Patients at GDS Level 5 may begin sundowning. This is where, during the afternoon or the evenings, the patient begins to wander, begins to have some behavioral issues, and increased confusion as the sun goes down. But at this stage, their wandering is typically still purposeful. They know they're going somewhere. They understand that they're trying to get somewhere. It's not an aimless type of wandering.

You will also see patients who have difficulty organizing their thoughts. You may see some insomnia. You are also going to see possible decreases in nutrition and hydration. Because of that attention span, these patients may suddenly leave their table during meals. Even though they're still able to feed themselves, they may have some difficulty with utensils. You may see some texture aversions that come about that weren't there before. There may be some differences in taste and smell.

These are also the patients who may resist changing their clothes. Because they want to wear the same clothes every single day. I've had nurses and families get really upset about that. And what I've said is, "You know what, let's get them five of their favorite outfit. When they get in the shower, we'll just set that outfit to the side and while they're getting a shower, we replace it with a clean outfit that looks the same.” Things like that can make a difference with some of the behavioral characteristics you may see. Because these patients do get easily overwhelmed.

You're also going to see visual perceptual deficits. The visual field is going to be about 14-17 inches. But there's going to be a lot of perceptual deficits.

GDS Level 5 - Therapy Focus. What should our therapy focus on? Focus on positive redirection, attention to tasks, sequencing, orientation, using a Montessori approach. These are all very valid focuses for therapy. We will go through more of those over the next couple of weeks.

GDS Level 6 – Severe Dementia

GDS Level 6 is an age equivalency of two to four years old. Think about what you see in a 2-4 year-old. What do they do at dinner? They may use fingers instead of utensils. They pick their food up. They want finger foods or they may try to cut their food with a spoon or eat their food with a knife. So, there's some difficulty recognizing utensils in this phase. They may also do things like try to put too much in their mouth at a time or talk with a mouthful of food. They may pour liquids on their food.

Behaviorally, you may see repetitive vocalizations. You may see random actions or patients that yell out. One of the major things that I really want you to take away from this series is that when we talk about the different stages of dementia and these behaviors, every behavior is an attempt to communicate something. We have to remember that. So, yelling out or yelling curse words may not be because of anger. It just may be that's the behavior that's manifesting because this patient is in pain, is afraid, is lonely, too hot or too cold, or needs to go to the bathroom.

At this stage, there is now a communication impairment. We have to know that not all behaviors need to be managed with antipsychotic medications. A lot of these behaviors can be mitigated by truly looking at the environment and assessing the environment, assessing what the patient's intent may be, and then becoming one with that patient using a validation approach. We will talk more about that approach later.

At a GDS Level 6, you have a visual field of about seven inches. There's not going to be much peripheral vision. If you come up behind or beside a patient and suddenly start talking to them, they may jump and scream and take a swing at you. It may be that it was a fight-or-flight instinct because you weren't within their visual field.

This stage can last anywhere from six months to a year to about three years. This is the next to the last stage so it is typically shorter.

You'll also see patients who only want to eat sweets. They want cakes and desserts, and forget the protein. You can actually kind of trick the mind a little bit by putting sugar on the food if you're trying to increase PO intake. I know that for us who have normal cognition, that seems really weird. But if it helps trigger that taste sensation for the patient and it helps the patient eat more, then great. You're also going to see them start pocketing food, forgetting food is there, or overstuffing their mouths oftentimes.

Patients at a GDS 6 may also not recognize their family members, and they have poor impulse control. You're going to see some weight loss. Patients can still participate in activities but they need those abilities to be simple.

GDS Level 6- Therapy Focus. Again, we have to focus on simple, functional communication and their immediate surroundings. We're not going to focus on, what they need to do to go out to the store or how to manage their money. At a GDS 6, that's really a moot point. We need to focus on communication with staff and interaction with their surroundings.

GDS Level 7 – Late Stage Dementia

GDS Level 7 is the end stage of dementia. A study by Gillick said that only about a third of patients who are diagnosed with dementia actually live to a GDS 7. This stage is relatively short, maximum of about two years. The age equivalency is an infant. You'll see a pound and a half to two pounds of brain tissue loss. So that's significant. You're going to have significant neurological deficits.

This is often where you see oral apraxia and oral acceptance deficits. There will be a lot of dysphagia going on, having difficulty swallowing, patients who completely stop eating all together or who suddenly have texture aversions. There is a high aspiration risk.

These patients require total care. Most of them are bed-bound at this end-stage. But that doesn't mean they're completely “out of it”. Soothing sounds, music, reminiscence-type sights, smells and sounds can positively affect the patient.

These are patients who are going to reach out and grab things. That could include your drink, your clothing or your wrist. If you think about an infant, they're grabbing things to try to get your attention. But typically, there are very few words in this end stage. You'll see a lot of sleeping. At this point, typically, patients do not recognize their family members. They may understand that they are someone who is around a lot but they may not be putting two and two together to say, “This is my husband.”

At a GDS Level 7, our therapy should really be focused on assessing how this patient is communicating. What are their gestures, their nonverbal communications, and facial expressions? We want to be communicating those things to the staff too so that they can take care of those patients in the best way possible.

How Does the SLP Intervene

Why Is Testing Important?

How do we get these stages and how do we start? We have to have a strong evaluation to start. Our testing is vitally important, because not only does it help us stage the patient, but it may unmask things that your typical questioning with the family or with the patient may not give you. It also provides you an objective measurement that allows you throughout the plan of care to show progress, even if it's progress in just one area of a subtest. Maybe it's not a full level of the GDS. But objective testing can help you show that, for example, in the area of word-finding, this patient has gotten better. Their short-term memory's still not great. But therapy has made a difference, and that justifies the therapy.

Unrecognized Cognitive Impairment

Testing also helps us with that unrecognized cognitive impairment. I really advocate for any patient who comes into a facility that has a diagnosis that we know causes cognitive decline, that we at least assess that patient. We've established a baseline for that patient. If there's no difficulty, fabulous. But if there is, then we've identified it early so that we don't have the major safety deficits and potentially catastrophic consequences.

Objective Data

Here are some of my favorite assessments. Some of them have websites and are available online. Some have cost, some are free.

- Brief Cognitive Rating Scale (BCRS)

- ASHA NOMS (if certified)

- BCAT (Brief Cognitive Assessment Tool, https://www.thebcat.com/)

- Montreal Cognitive Assessment (www.mocatest.org, 3 distinct protocols, plus MOCA BLIND)

- SAGE (Self-Administered GeroCognitive Evalulation, http://www.elderguru.com/download-the-self-administered-geocognitive-exam-sage-alzheimers-test/)

- SLUMS (http://www.elderguru.com/download-the-slums-dementia-alzheimers-test-exam/)

- Global Deterioration Scale (http://www.fhca.org/members/qi/clinadmin/global.pdf)

- Ross Information Processing Assessment- Geriatric (RIPA-G, Available through Pro-Ed)

- Memory Impairment Screen (http://www.alz.org/documents_custom/mis.pdf)

- TYM (Test Your Memory, http://www.tymtest.com/)

- General Practitioner Assessment of Cognition (GPCOG, http://www.alz.org/documents_custom/gpcog(english).pdf)

- Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (SHORT IQCODE, http://www.alz.org/documents_custom/ShortIQCode.V2.March15.pdf)

- Allen Cognitive Levels (OT, https://allencognitive.com/wp-content/uploads/Ed-Corner-Allen-Cognitive-Levels-and-Modes-of-PerformanceCombo.pdf)

- Medi-Cog/ Pillbox Assessment (https://www.pharmacy.umaryland.edu/media/SOP/medmanagementumarylandedu/MediCogBlank.pdf)

- Geriatric Depression Scale (can be used for QOL, http://geriatrictoolkit.missouri.edu/cog/GDS_SHORT_FORM.PDF)

- Blessed Orientation-Memory-Concentration Test (BOMC, http://geriatrictoolkit.missouri.edu/cog/bomc.pdf)

Lawson Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADLs) (4 areas that deal with cognition are: telephone use, transportation, medication, finance, http://www.healthcare.uiowa.edu/igec/tools/function/lawtonbrody.pdf)

So the BCAT, the Brief Cognitive Assessment Tool, has to be purchased, but it is a validated assessment. The Brief Cognitive Rating Scale is used frequently for staging. The MOCA is great because it has three different protocols that are all equally difficult. Sensitivity and specificity is equal for all three protocols. It also has the MoCA-BLIND, which is for low literacy or low visual acuity patients. I haven't seen if there are any changes with COVID, but as of this October (2020), you will need to be certified to give the MoCA. The SAGE is a great evaluation for higher-level patients. It has four different versions.

When you're thinking about assessing or evaluating a patient every few weeks, you want to repeat some type of objective measurement. Obviously, that doesn't mean you give the same exact assessment over and over again because you have learned effects. You don't want to skew your results. But with tests like the MoCA or the SAGE that have multiple protocols, you could give one version every week or two and really continue that objective measurement throughout the plan of care. You could also switch up which assessments you're giving.

I like the SLUMS for lower-level patients. The RIPA-G is another awesome assessment. You do have to pay for that one. There's a Memory Impairment Screen and Test Your Memory that are both available online. The GPCOG, the SHORT IQCODE are both available online. The Medi-Cog/Pillbox Assessment is good if you work with higher-level patients, go to that website and print it out. I love a medication management assessment because it is so pertinent for our patients who are going back home to be able to say, "Hey, we did a medication assessment and here's what we found."

Other Measures

- FAST (Functional Assessment Staging Tool)

- AD-8 (8-item informant interview to differentiate Aging and Dementia, https://www.alz.org/media/Documents/ad8-dementia-screening.pdf)

- Executive Function Tools:

- Mini-Mental Status Exam (MMSE)

- Trail Making Test- oral version (TMT)

- Clock Drawing Executive Test (CLOX)

- Brief Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF)

- Reading/Writing Tests:

- Woodcock Reading Mastery Test (WRMT)

- Reading Comprehension Battery for Aphasia (RCBA-2)

- Functional Assessment of Communication Skills for Adults (FACS- from ASHA)

Some other measures include the FAST and the AD-8. There are some executive function tools and some reading and writing tests. I could go on all day with all the different assessments. But I just want you to have a copy of those in your handout. Make sure you look at specific objective scores and specific areas of deficits.

Evaluation

Brief Cognitive Rating Scale

The Brief Cognitive Rating Scale is a scale that can be found online and will allow you to have a Global Deterioration Scale level, the GDS level. And you can find that online. These are the directions for it:

- List of questions presented in a conversational manner to the patient. Mark each correct/incorrect

- 5 domains of language/cognition addressed

- Axis 1: Concentration

- Axis 2: Recent Memory

- Axis 3: Past Memory

- Axis 4: Orientation

- Axis 5: Functioning and Self Care

- Mark each incorrect response

- Highest number value of incorrect responses in each category is the score for that category.

- Total score of all items is divided by 5 to get the GDS level

Assessment of the Non-Verbal Patient

With those GDS 6s, late 6s and 7s, when you have a nonverbal patient, this is where I see a lot of therapists struggle. They either struggle with the really high level or the really low level. There are a few assessments that are available for patients who are nonverbal. We don't need to forget about the fact that our patients do communicate in other ways than with words.

- DS-DAT (Discomfort Scale - Dementia of Alzheimer’s Type, https://hhs.texas.gov/sites/default/files/documents/doing-business-with-hhs/provider-portal/QMP/dementiapainscale.pdf)

- CNPI (Checklist of Nonverbal Pain Indicators)

- PAIN-AD (Pain Scale - Alzheimer’s Dementia, http://geriatrictoolkit.missouri.edu/cog/AJN-Pain-Assess-108.7.2008.pdf)

- PACSLAC (Pain Assessment Checklist for Seniors with Severe Dementia)

Using the Correct Evaluation CPT Code

Here is some information on evaluation CPT codes.

92523- Evaluation of speech production (e.g., articulation, phonological process, apraxia, dysarthria); WITH evaluation of language comprehension and expression (e.g., receptive and expressive language)

- Use if you are assessing cognition using non-standardized tests in conjunction with a full speech-language evaluation.

- Cognitive-Linguistic disorders

- Ex. BCRS

- Usually used with 92507 treatment diagnosis

96125- Standardized cognitive performance testing (e.g., Ross Information Processing Assessment, MOCA, SLUMS) per hour of a qualified health care professional’s time, both face-to-face time administering tests to the patient and time interpreting these test results and preparing the report. Subtests of standardized tests may be used if the subtests themselves are standardized.

- Norm-referenced or criterion-referenced

- Subtests can be used, but need to be standardized

- Ex. RIPA-G, MOCA, etc.

- Usually used with 92532 treatment

I will say that working in the long-term care setting, it is rare that I use the 96125. In my experience, that code is great for traumatic brain injury or a specific neurological accident, for patients who are definitely going back out in the community, that need standardized cognitive performance testing. But with the post-acute care and long-term care settings, we really use more of a 92523 because we're looking at cognitive-linguistic disorders. We're looking at how cognition and language overlap. So I've had people say, "Well, what about dementia? Does the diagnosis of dementia mean I can't treat my patient?" No. You cannot be denied services simply because of a diagnosis. You used to be able to be denied coverage. But back in, I think it was 2013, 2012, 2013, Jimmo versus Sebelius happened. And after this major court ruling, progressive neurological conditions, ALS, MS, Parkinson's disease, dementia could no longer be denied simply because of that diagnosis.

Primary Medical Diagnoses

You didn't have an "improvement standard" anymore. It's not how much the patient improves. It's about what are the skilled services that you are providing as a therapist that only you can provide. And you do want to give an appropriate primary medical diagnosis code that fits what caused the decline that you're treating the patient for.

Simply because the patient has a dementia diagnosis does not always mean that is the primary medical diagnosis. Sometimes, as we know, dementia can be superimposed upon by anesthesia or infection, for example. The new decline that didn't spontaneously recover was caused by those things occurring over and above the dementia.

Documentation Matters

It's very important that we document the skill of our services. So what did we do and how did we analyze skills that only our profession, as speech-language pathologists, are able to do? We have to be very clear in how we document and ASHA has some documentation templates (http://www.asha.org/slp/healthcare/AdultTemplates/). I know many companies are using computer or online documentation now so you may have your own template for your company. But if you don't, ASHA has an example. I've listed a few things that are included in an evaluation just in case you don't have a template:

- MD Order!!! (for evaluation and treatment)

- Diagnoses (medical and treatment)

- Assessment type description of scores

- Long-term goals and related short-term goals

- Type, amount, frequency, and duration of services

- Documentation of medical necessity of services

Below is a list of what should be included in progress notes.

- Assessment of current level of function for each goal

- Additional evaluation results

- Recommendation for continued treatment

- Revisions of any goals

- Statement to justify the medical necessity of services provided during reporting period

Be sure to update objective testing results. Update the specific subtest. Update the specific goals and the progress made. If the patient doesn't make progress, don't keep doing the same thing over and over and expect a different result. Change your approach. Change the time of day that you do therapy. Change the environment in which you do therapy. Change the strategies or the amount of cueing. We understand that regression can happen and plateau can happen. But we don't just keep doing the same thing over and over again when that occurs. Sometimes it may just be something as simple as the patient had a specific procedure this week or had a fever this week, and the patient declined. And we document that by saying the patient is being treated for xyz. Then, hopefully, next week progress starts again.

Skilled Therapy Examples

I have mentioned skilled therapy a couple of times today and I will be giving you some documentation examples in Part 4 for what skilled daily notes look like. But here are examples of what therapists do that are skilled.

- Analyze data and select appropriate evaluation tools

- Design plan of care

- Develop and deliver evidence-based treatments that reflect a hierarchy of complexity

- Modify activities during treatment

- Increase or decrease complexity of task

- Increase or decrease cueing

- Increase or decrease criteria for success

- Introduce new task

Think of the verbiage: analyze, design, develop, modify, engage, instruct, evaluate. Think of the verbs that you do day in and day out. Anything that is rote, repetitive, observational in nature is not necessarily skilled. Any type of wording that suggests the patient could do this on their own or that anyone could do without showing the strategies that you were using or the evidence-based practice concepts that you were using, that's when you'd see words like, "tolerated treatment well," "continued plan of care," "performed 80% word-finding," "problem-solving four out of five attempts." That doesn't describe what the therapist did. So make sure you include that.

In Part 3, we will review evidence-based treatment strategies and how they fit into our different stages of dementia. Then in Part 4, we'll get really into functional therapy and documentation.

Questions and Answers

What suggestions do you have for a retired family physician who definitely seems to have dementia but is in denial, won't bring it up to his doctor, probably needs meds, and his wife is fearful of mentioning it to his doctor?

Are you talking about my family member? Because I have one just like that right now. Not a physician, but very similar. I actually had this with my own grandmother. You know, denial is something that I understand. But when I spoke to my grandmother's physician, I started explaining some of the things we were seeing. For my current family member who's showing a lot of these signs, my mom and her sister are very involved with the wife, who is fearful of mentioning this to the doctor. But they've done things like drive her to the doctor, and then during the doctor's visit they were actually able to say, "Oh, Mom, did you tell this doctor about such and such?" So it was done kind of in a conversational way to not put anyone on the spot.

How often is cognitive intervention prescribed for GDS 7?

With GDS 7, this isn't something that's going to be long-term. It's really more staff education. So personally, I typically will take as long as it requires to educate the appropriate staff, to come back around and assure them that they're able to use the strategies I've taught them. Typically, for me, that's three or four sessions.

For individuals who already had intellectual disabilities, acquired brain injury, learning disabilities, etc. do you typically see a more rapid progression through the stages?

] I don't know that I would say a rapid progression, but I would absolutely be interested to see the research on that. I've seen patients whose progression sped up due to other medical conditions, such as infection and anesthesia. Those things can speed it up. But existing cognitive or intellectual disabilities, I'm not sure. It would be interesting to investigate that.

Should we expect to see "progress" in dementia, which is a progressively worsening type of disease? Would you consider a "lack of worsening" to be progress?

So, in a few words, people with dementia can make progress. We may not see global, overall progress, like an improved GDS level, for instance. But if we see progress in a specific skill, then that's great. If we are able to put into place some compensatory strategies in order to make up for some of the deficits or to slow the progression, then that really is progress.

We always complete an initial assessment and then a discharge reassessment. I like to use the BCRS and GDS. However, do you think with those that a discharge reassessment is warranted? I've been doing this, but I never see a huge improvement in the stage other than a few points difference in the overall score.

Yes, absolutely, that's a great example. I would suggest, if you can, to use another assessment in addition so that you are able to show smaller amounts of improvement. It may not be a huge, global improvement. But let's say that the patient was a GDS 3.4. So they're still planning on going home. Well, if we did a pillbox assessment, and then at the end of therapy, they're now able to manage their own medications, and we've documented that, I don't see any payer saying, "Oh, they didn't make progress," when we can clearly show, hey, they're at less risk for rehospitalization, because guess what? They have to manage their own medication now, and here's the objective data to support that. So just add little bits of some of these other assessments in there.

You provided a big list of evaluation tools which is great, but I'm feeling a little overwhelmed and am wondering if you have two or three go-to tools that you recommend starting with.

So higher-level patients, of course, the BCRS and the GDS are always my go-to's because I believe in staging. But for higher-level, do the SAGE, the pillbox assessment or Medi-Cog, and the RUDAS, the Ross Universal Dementia Scale. For middle stage, I really like the MoCA. For kind of the later stages, like GDS 5/6, I like the SLUMS.

Comment: I am an AAC specialist and my father has dementia. I have created some visual sequences for kind of ADL-type routines like getting dressed and brushing teeth and washing hands and so forth. My father was able to use those visual cues to stay pretty independent, at least with those basic ADL tasks. They were taped up on the wall in his bathroom. Those are a few examples of using some compensatory strategies and external cues.

Citation

Heape, A. (2020). Dementia Diaries Part 2: Staging on the Severity Continuum. SpeechPathology.com, Article 20402. Available from www.speechpathology.com