Editor’s Note: This text is a transcript of the course, Decision-Making for Alternate Nutrition and Hydration - Part 1 presented by Denise Dougherty, MA, SLP.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Describe the impact of culture and religion on the ANH decision-making process.

- Identify two advance directives that allow patients to make their choices known.

- List criteria that are important to the patient and family when making decisions about alternate nutrition and hydration.

Introduction

In Part 1, we're going to look at the concerns that impact the decision-making process from the patient and family perspective. We'll be talking about religious and cultural beliefs; beliefs that they bring to the table that we may not be aware of. We'll talk about advance directives that you may find in your patient's medical charts. I will also have a lot of resources for you to review and use when you're discussing these options with patients. Finally, I will discuss the criteria that patients and families may be considering when making these decisions.

Artificial Nutrition

Let’s start with an overview of what we know. One of the options that we may be looking at for our patients is a short-term placement. This is usually done with the NG tube, but there is a high rate of pulmonary aspiration and many of our patients will self-extubate. Even the staff can sometimes inadvertently pull the tube and it's no longer in the right place. Of course, this can cause complications. It's also possible that if the patient has a really vigorous cough or vomiting episode, the tube can migrate upward and put them at risk.

In my experience with NG tubes, x-rays are taken to make sure that the tube is placed in the right position. However, even if the tube is in the right position, other issues can occur. For example, tubes can actually kink. With one patient, when we turned on the fluoro for the modified, we noticed that the tube went down over the base of the tongue, hit the epiglottitis, and kinked. It came back up past the velum and into the nasal passage. It then came back down and went in the right direction. So, every time this patient was swallowing, her epiglottitis was hitting three NG tubes. Obviously, this patient was very miserable. So, the tube can kink and we need to watch out for that.

When we're looking at more long-term placement, usually we're recommending a PEG or possibly a J-tube but there can still be an aspiration event with those. So, there can be problems that need to be discussed when we talk about informed consent or informed refusal with PEGs.

Hypodermoclysis (HDC)

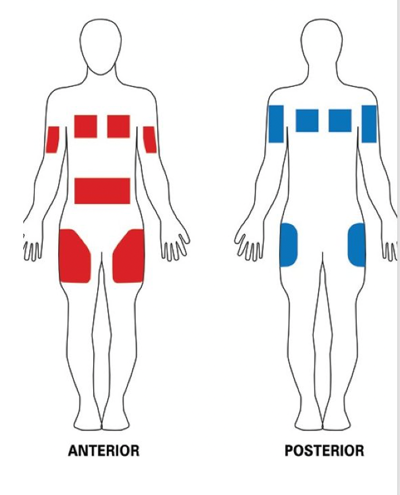

An IV can be used to rehydrate a patient, but another option is hypodermoclysis (HDC). This is done by placing a needle under the skin in order to rehydrate patients who have a mild to moderate dehydration. The below images show the different positions where it may be placed.

Figure 1. HDC placement.

It can be placed on the thigh, or if a patient has a tendency to grab at IVs, etc, it can be put on the shoulder blade area, which is harder for them to reach. The nice thing about HDC is that it's four times less expensive than an IV. It reduces the nursing care compared to an IV and it's easy to use. It can be used in the nursing facility as well as at home by the patients. Caregivers can be trained as well.

Comfort Feeding

If we feel a patient may not be appropriate for an NG or a PEG, especially when we're looking at advanced dementia, we could move into comfort feeding. The ethics subcommittee of the Society for Post-Acute and Long-term Care Medicine suggests comfort feeding as long as the patient is willing to accept the food and drink, and we would stop at the first sign of distress.

In many facilities that I've worked, we will often feed patients throughout the day rather than just breakfast, lunch, and dinner. It could be five or six times a day. Basically, whenever the patient is willing to accept it, we're going to offer it. We give the caregivers and the nursing staff signs to look for that indicate maybe you need to stop. For example, if the patient begins to cough or their breathing pattern has changed from when you started. You want to document that you did the comfort feeding until the patient exhibited signs of distress and identify that.

Comfort feeding is a way that we can provide oral intake for our patients who have advanced dementia. It is suggested that tubes should rarely be placed, if at all, in a patient who has advanced dementia. However, we know that sometimes that happens.

ANH and Dementia

When looking at regulations, there can be institutional policies to ensure adequate nutrition and hydration. There can also be regulations that your facility needs to work within to make sure that patients get the nutrition and hydration that they need. But sometimes those policies can inadvertently impose requirements on a patient who has advanced dementia. So, we need to look at what works for the patient at this particular time and go from there.

A 2009 study found only 1 in 3 healthcare proxies reported that the doctor discussed the trajectory that dementia takes. They were never informed about how the disease progresses. They were never told about the complications their loved one would experience such as feeding problems or involuntary weight loss. They were never told that information.

In a 2012 study, researchers looked at 36,000 patients in a nursing home who had advanced dementia and a feeding tube. Of those 36,000, they found only about 5.4% of those residents had a minimal difference in survival benefit versus those who did not have the feeding tube and remained as an oral feeder.

American Geriatrics Society

The American Geriatrics Society suggests careful, attentive hand-feeding. When researchers looked at attentive hand-feeding versus tube feed, the outcomes were basically the same. Tube feeding is certainly much more invasive and there is a 30-day mortality rate with patients who have the feeding tube placed. So the researchers felt that a careful, attentive hand-feeding would be a better option.

They discuss different types of feeding: direct, hand-over-hand, and underhand. When they looked at how much time it takes to feed an individual, each one of these methods took about the same time. They did not find that one was quicker than the others. They also thought that using underhand or direct hand was better at managing the feeding behaviors that we often see in this population (e.g., turning the head away, clamping the mouth shut). It was easier to manage those behaviors when feeding patients when using underhand or direct hand.

When caregivers are feeding these individuals, they require some skills. They need to know how to manage the dysphasia and how to minimize the risk of aspiration. They need to know how to interpret and manage the feeding behaviors that our patients are exhibiting. We want the patient to feed themselves as long as they can. We want them to be independent, but there's a point where we need to do some assistance.

When researchers compared individuals who had the assisted hand-feeding versus NG tubes, they found no increased rate of hospitalization if they were fed versus having an NG. In fact, when they looked at patients who had the NG tube, those individuals had an increased risk of pneumonia.

Feeding Techniques

Let’s review the feeding techniques. I want to, first, address graded assistance. We've all seen staff say to patients in the dining room, “Pick up your spoon and eat,” and the patient doesn't understand what they are saying. If we use graded assistance with that individual, that simply means we're preparing the person for the bite, but they're doing the self-feeding. We want the patient to sell-feed as long as possible because every time they bring food to their own mouth, they are getting messages to the brain saying, “Get ready something is coming,” and they're prepared. With graded assistance, you're putting the bite on the utensil, you're putting the utensil in their hand, and you're giving them a little kind of a jumpstart. They have that reminder, “Okay, I need to bring the hand up.” When they put the food in their mouth, they put the utensil down, they chew, they swallow. That is the graded assistance. Technically they're doing the self-feeding, you are just getting them ready and giving them the cue to get the arm up.

We can also do hand-over-hand. This is where the patient holds the utensil, but they need some help getting the food from the plate to the mouth. In this case, you're putting your hand over their hand and you're gently bringing everything up to the mouth. There are some individuals that really don't like you helping them that much, and they get a little bit feisty and lash out. Always look at your patients. As much as you would like to use these techniques, they may get agitated.

With underhand, the patient can't hold the utensil. You're going to put your hand under theirs and guide the utensil up to the mouth. Again, the hand is moving, they're getting that sensory input to the brain saying, “Get ready something is coming.”

Then, we can also do direct hand where we are going to spoon-feed the individual. The literature recommends that you save this method for late-stage dementia. If you come in too quickly and feed this individual, you're actually creating excess disability. We want to hold off and keep the person as independent as we can. We also want to make sure when we use this technique that they can see the food coming. We don’t want it to be a surprise when all of a sudden you have a spoon that you are trying to get in their mouth.

Patient-Specific Choices

We want choices to be patient-specific. This is not a cookie-cutter approach. When we say there are no right or wrong answers, we are saying it for that patient. You need to forget the cookie-cutter and look at the individual, their set of circumstances, and factor in everything. Is this a good recommendation?

We can offer patients a trial of alternate nutrition and hydration, but we need to be very clear that we're only going to do it for this amount of time, this many weeks, this many months. If the patient doesn’t like their quality of life after this timeframe, then we're done and we will take it out.

We can do short-term, which would be the NG. We could do the long-term, which is the PEG. Finally, patients can say, “Thanks, but no thanks.” We have a lot of families and patients that say, "You know what? Food is my last pleasure in life and I want my pie. I want my cake. I want my coffee.”

If a patient has decision-making capacity, then that's their choice. They have every right to make that decision for themselves. If they don't have decision-making capacity, then we need to look at the surrogate decision-maker, the healthcare proxy. So, there are a lot of different options that we can present to this patient. But we need to look at the set of circumstances to determine what those options are and make sure that we're doing the education. We want this individual to make an educated, informed decision, whatever it is.

Statistics

A conservative estimate for what tube feeding costs per year is about $32,000 per person. When a person uses a feeding tube, there is going to be disuse atrophy of the muscles. The patient is not swallowing except for saliva and many patients don’t even have saliva to swallow. As a result, there is very little movement of the muscles and we end up with disuse atrophy.

It has been suggested that even one week in bed leads to substantial muscle disuse. If a patient doesn't have saliva and they are NPO, then they are not swallowing anything. So, we're going to see some really involved atrophy.

Giselle Mann suggests that if disuse atrophy kicks in within 72 hours the following measurable results occur:

- Impact on swallowing muscles great

- High % of fast-twitch fibers

- Difficult to reverse without normal swallow (especially if on a modified diet or PEG)

Advanced Dementia (AD) and PEG

There is a general consensus among gastroenterologists in the United States that there was absolutely no benefit to placing a PEG for anyone who had advanced dementia. What they found was, looking at individuals who had an advanced dementia diagnosis in a nursing home and had a PEG, almost 20% of those individuals had to have the tube replaced or repositioned in a two-year period when they did follow up. That tube replacement or repositioning resulted in more emergency room visits. So, the cost of healthcare went up with that feeding tube. They also found that nearly one-third of those individuals who did have the tube replaced needed it replaced at least twice.

The timeframe for survival after repositioning or replacement, it's about 54 days. That is the median survival. When individuals have a PEG placed, there's a high 30-day mortality rate with that. Therefore, we want to be very careful with these recommendations.

When researchers looked at individuals who had an NG tube, they were at a much higher risk for death versus those individuals who were fed orally. Also, there's the issue of survival. When a PEG-fed group versus the oral-fed group were compared to each other, it was found that the PEG-fed individuals do not survive as long as those individuals who continue with oral feeding.

Costs

A study was conducted to determine the cost of hand-feeding versus tube feeding. A very small cohort of 11 individuals was included in the study. It was found that the cost of hand-feeding a patient was much higher than the cost for a patient who was tube-fed. It wasn't as labor-intensive.

However, when they looked at the costs that were billed to Medicare for patients with feeding tubes, they had higher costs than the patients who were hand-fed. The reason for this is because of the cost of placement of the feeding tube, the complications that send them to the emergency room, and the higher costs of their inpatient care. So, tube feeding is more expensive when they send the bills to Medicare.

They also found that if a patient had advanced dementia, a feeding tube feed, and they were in a nursing home, they had higher odds of spending time in the ICU. Therefore, their cost of healthcare went up and complications went up, and it was all related to the feeding tube.

Decision: Numerous Viewpoints

When considering options for our patients, everybody comes to the table with certain viewpoints. As SLPs, we know the disease process. We know what is going to happen over the course of this disease. We know the benefits and the burdens. We've reviewed the research and we know the good things and the bad things that happen.

It's our job to educate the patient and the family about the options, along with the pros and the cons. The patient and the family come to us with a whole set of other issues and beliefs. We have to consider the quality of life (i.e., this is not the quality of life I want or I want for my loved one, there is no feeding tube, food is their pleasure in life, I want them to eat, etc.).

They have religious viewpoints and cultural viewpoints. Sometimes we can be in a “battle” with my belief system versus their belief system. But, we can really reduce the number of clashes that could potential occur if we understand their viewpoints and where they're coming from.

Health Literacy & Patient-Centered Care

There is literature that discusses the combination of health literacy and patient-centered care. The options that we offer our patients should be respectful of and responsive to the patient's preferences, their values, and their needs, rather than “this is just how we treat Parkinson's”, or “this is just how we treat advanced dementia.” We're looking at the patient.

We're also looking at health literacy and making sure that whatever literature we give to families and patients is something they can comprehend. We go to school for a long time to learn all of these big words but we can't use them with anyone because nobody knows what "xerostomia" is. We need to take it down, sometimes several notches, for the patient and the family to actually understand. We also need to recognize the cultural, religious, and social values that come into play. If we're not recognizing those then we're not going to have good communication, and the healthcare experience suffers for this individual.

The teach-back technique is something that is recommended. I'm sure many of you are using that already. We use this a lot in home health. With this technique, we're going to explain or demonstrate exercises, how to process food, how to thicken their liquid, etc. After we give the explanation or demonstration, the patient or family explains how to do it or demonstrates that they know what we were talking about. If they can't do that, then we need to go back and provide that education again. Not only do I like to give verbal instruction, but I will leave them with a handout as well. That way they have something to refer to once I leave their home or they leave the office.

Our handouts and reading materials need to have good readability. If the patient or family doesn’t understand the information then they may misinterpret it. They may not ask what terms mean because that reflects badly on them. So, our handouts and pamphlets, etc. need to be written at about a fifth-grade reading level. You'll see other sources that talk about the seventh or eighth-grade reading level, but it needs to be something that they can comprehend. They need to be able to understand what we're saying and then be able to follow through.

USA Weekend stated that patients forget about 40 to 80% of the information when they leave the office (2009). Meaning, they can explain everything to you, but as soon as they leave, they forget much of it. So be sure to get that explanation and also be sure that everything is in writing so that they have something to refer to.

There is a guide available called “Simply Put” that is a resource for creating easy-to-understand materials. It gives you a test for readability, and that allows you to bring it to a level where the patient and family can comprehend the information.

PATIENT: Many Influential Factors to Consider

From the patient's standpoint, there are many factors to consider. Certainly, we know there's a disease process, but there is also their quality of life which is a huge factor. There are cultural and religious considerations. It’s a combination of those factors that can get in the way or changes their willingness to go with the options that we present.

There can be a culture clash between the patient and the healthcare providers because everybody is coming to the table with their own experiences, and many times they're not the same. There is a great resource that I highly recommend you download called the "Patients' Spiritual and Cultural Values for Healthcare Professionals" (www.healthcarechaplaincy.org). It's an 89-page handbook that discusses western, eastern, and other religions and cultures. It covers an amazing amount of information.

Cultures and Religion: An Overview

I want to discuss some cultures and religions, but as a quick overview. The handbook I mentioned above should provide all the information you need to look at religion and culture. We know in the United States about one-third of the population is made up of ethnic minorities. Many times, when we're working with minority populations, they want to hide the information and the truth from their loved ones. They want to protect their loved ones from the truth, they want them to enjoy their last days, they know what's best for the patient.

I always like to talk to my social workers because they've had more contact with the family perhaps than I have had. I may just see the patient, but they've seen the whole picture so they can give me ideas about who the go-to person is or who the healthcare proxy is. Sometimes we think it's the family member who’s in visiting all the time and it's not. So, we always want to direct our information to the person who is making the decisions.

We also have to be very careful not to generalize because there's always going to be somebody who doesn't really follow the book on what their culture or religion states. As we go through the different cultures and when you read that handbook, we will talk about eye contact and personal space. How close can you come to this person before they feel violated or that you're in their space? Sometimes when we're talking to an individual, they may not make eye contact, and we could be very put off by that. But it's possible that in their culture, we're considered an authoritative figure and it is respectful not to look at us. We could take it as an insult when really, they're showing us respect.

European American

Generally speaking, European-Americans favor directives. They want treatment limited at the end of life. Additionally, European-Americans are primarily future-oriented, prefer direct eye contact and large amounts of personal space. They tend to value privacy and want a low to moderate amount of touching.

Asian/Middle-Eastern

Asian and Middle Eastern families tend to make decisions to protect the patient from bad news. They are unlikely to make eye contact because, again, you're considered to be an authoritative figure and they are showing you respect by not making eye contact. Additionally, they tend to need only a small amount of personal space and there is little touching in public.

African-American

In general, African-Americans prefer aggressive treatment rather than limited. They're more likely to be discharged to an extended care facility and twice as likely to request life-sustaining treatment, if death is inevitable, compared to Caucasians.

Older African-Americans. Depending on the part of the country that you're working in, older African-American individuals may have a real distrust of the healthcare system because of segregation and discrimination. I think we've seen a bit of that with the vaccine discussion that's been on everybody's radar.

Older African-Americans may also have very strong religious beliefs. You might speak with somebody who is considered to be “fictive kin”. This an individual who's considered to be family, but they're not a blood relative. Additionally, they are primarily present-oriented, prefer direct eye contact, a moderate amount of touching, and are comfortable with small personal space.

Native American

Native Americans tend to reject directives. In fact, it may be the tribal leader who makes the decision. They focus on self-fulfilling prophecy in many cases (i.e., “As long as we don't talk about it, it won't happen.”) So, the minute you put it out there, then it's going to happen. You shouldn't have said anything.

Similar to other cultures, they are primarily present-oriented, unlikely to make direct eye contact with those in authoritative roles, and a small amount of personal space with the use of light touch is generally preferred.

Hispanics

Generally speaking, Hispanics, don’t usually institutionalize or take advantage of hospice because they believe that denotes a “giving up”. They're more likely to have CPR alternative forms of nutrition and hydration and intubation compared to Caucasians.

With Mexican-Americans, many times there is a belief that the doctor knows best, and they could be heavily influenced by the Catholic faith. The family typically wants to spare the individual pain, so they will make decisions for them.

Japanese

In Japanese culture, the patient may defer to the family or the doctor to make the decision about ANH. In a particular study, 30% of individuals who were surveyed believed that ANH relieves symptoms. When Japanese oncologists were surveyed, 24% said that withdrawing life-supporting treatment was never ethically justified. Therefore, once you placed a feeding tube, it was not going to be taken out.

They also believe that IVs are the minimum standard of care and the same holds true with alternate forms of nutrition and hydration, that is the minimum standard of care. So, again, once they have it, it will be continued until death.

Chinese

Within Chinese culture, “eating is as important as the emperor.” Food is really important and has a lot of significance. They often believe that if the patient isn't eating and they're “starving to death,” they will become a starving soul after death.

Individuals may utilize Chinese medicine and herbal remedies because that is part of their culture. Additionally, the eldest male child tends to be the primary decision-maker so you're going to only work with that individual.

Hong Kong Chinese

Hong Kong Chinese commonly uses ANH if there is insufficient intake or there is a risk of aspiration. They believe tube feeding is only a medical intervention when you're administering medications. They also think that if there is a problem with the swallow, it is a disease complication that you need to fix or treat.

Indian

Indian culture often practices alternative medicines. They believe that hospice is a place where individuals who don't have families go to die. There is typically a lot of withholding information from the patient. Feeding the terminally ill is symbolic. It gives the family more time with the patient and it's a basic act of caring.

Hospice Foundation of America

A five-year study was conducted in Northern California. Results of the study found that Hispanics, Asians, and Pacific Islanders were 5.2 times more likely to have alternative forms of nutrition and hydration at death versus non-Hispanic Caucasians.

Religious Beliefs

Most people have some religious beliefs. They could be spiritual, rather than “I am a very strict churchgoer”. So, it's important to be knowledgeable about religious beliefs and respect them in discussions with families and patients.

There's a list of religions where the patient has the right to decide they don't want any extraordinary effort.

- American Baptist

- Episcopal

- Buddhism

- Hinduism

- Islam

- Jehovah’s Witness

- Lutheran Missouri Synod

- Presbyterian

- 7th Day Adventist

Roman Catholic

With Roman Catholics, it is believed that alternate forms of nutrition and hydration are appropriate if the benefits outweigh the burdens. So as long as there's more good than bad, it's perfectly okay. At one time, Pope John Paul made a statement about withdrawing ANH in patients with PVS (persistent vegetative state). He felt that was euthanasia because tube feeding was not a medical act. It was something that we were obligated to do and it was moral. However, he was referring to a persistent vegetative state, not any other terminal states, and it seemed to be misinterpreted.

Protestants

Protestants are comfortable with life-sustaining therapies. The general thought is if there's little hope for recovery, most would understand and accept withholding or withdrawal of therapy. So, we either don't do it or if we placed the PEG, we can take it out. But taking it out is so hard, it's harder than not doing it, to begin with.

Greek Orthodox

Withholding or withdrawing is not allowed even if there's no prospect of recovery. It is also believed that the task of Christians is to pray, not decide about life/death. They did not have a position on end-of-life (EOL) decisions.

Jewish

There are a number of different sects in the Jewish religion with Orthodox Jews tending to be the most religious. Generally speaking, food and fluids are considered to be basic needs rather than treatments. But if a patient is in their final day, food and fluids may be withheld if that is what the patient wishes. In reality, at the end of life, most patients really aren't eating and drinking anyway.

There are the Four Tenets of Jewish and Secular Medical Ethics which is very similar to what we see in our ethics. These tenets include being able to make your own choices, benefits versus burdens, and avoiding doing harm.

Islamic Faith

In the Islamic faith, basic nutrition should not be discontinued. To do so is considered to be a crime in this religion. Other Islamic beliefs include:

- May withhold/withdraw life-sustaining treatments if terminally ill

- Death inevitable and treatment won’t improve condition

- May allow death to take a natural course and withdraw futile treatment

- Never hasten death

Hindu and Sikh

In the Hindu religion, Karma is an important belief. There is the idea of good death versus bad death, and it all goes back to reincarnation. A bad death would be in ICU. Many times, this individual has a do not resuscitate (DNR) so the person has a peaceful death. Additionally, the patient does not have autonomy to request or forgo ANH. That decision is left to the family.

Buddhist & Confucian

The Buddhist religion doesn’t really state anything as far as mandatory use of ANH. While Confucian belief is that the family or community should have all of the information and protect the patient from that information.

Additional Religious Consideration

Again, when we're making decisions, especially at the end of life, there are a lot of factors to consider. If we are working with individuals who have immigrated, especially recent immigrants, it’s important to know that those individuals tend to adhere to the religion and culture from their country. However, those who are second or third generation may be more interested in adopting the religion and/or culture of the new country. Interestingly, there are a few studies that indicate that even though some patients may have adopted the new culture and/or religion, when they are facing death they tend to revert back to their traditional cultural beliefs.

Patient and Advance Directives

When it comes to advance directives, we want to consider Advance Care Planning (ACP). Here's where we run into problems. These types of conversations don't typically happen until the patient is in the hospital, they're actively dying or they're refusing to eat. We need to be talking with the families and patients at the time they receive the diagnosis. We need to discuss with them how the disease or disorder is going to progress so they know how to prepare. Have these discussions with the patient while they have decisional capacity and can make their own choices. If they wait too long, we may not really know what they want.

This is really important now that we're dealing with COVID. We are seeing that a patient goes into the hospital and they're young and healthy. Then the next thing you hear from the family is that they are near death. There are actually resources to help us talk about how to prepare for COVID. What the patient and family can do now. One resource is called "Proactive planning, be prepared and take control". So there's a lot of information out there. It can happen to any of us. Are we prepared for that possibility? What are our choices?

Decisional Incapacity

The literature shows that approximately 40% of individuals in hospice or adult inpatients were unable to make their own medical decisions. That percentage was about 90% for those who were in ICU.

In general, for the United States population, only between 20-29% of individuals have advance directives. So, when there's a crisis, who makes the decision? The research also indicated that 70% of the elderly who were in their final days did not have decisional capacity.

Again, if we think about COVID, you're healthy and suddenly we have a crisis, and we weren't prepared. We didn't identify a healthcare proxy, surrogate decision-maker, and we certainly didn't communicate what we would want. With COVID, there is a place for alternate forms of nutrition and hydration.

Palliative Care and Hospice

Palliative care reduces the healthcare burden, the cost of healthcare, and eliminates unwanted care. An individual can eat by mouth if they choose to do so. When a patient is in palliative care and moves into hospice, there are fewer emergency room visits. So, we can help the family and the patient discuss and come to grips with decisions that they need to make, given all the information. We want their decisions to be informed, educated choices.

When we move into hospice, we want a patient’s last days to be quality days for them. You certainly can have hospice in a nursing facility. Bereavement counseling is often provided many times for up to a year. There were studies published in the New England Journal of Medicine looking at patients with a number of different types of cancer. They found that if the patients were in hospice, they live longer than those individuals who did not receive hospice care. So, that is something to consider.

Comfort Measures

Comfort measures are for keeping the patient comfortable. We're not doing a feeding tube. We're allowing them to eat as they feel up to it. There's a Do Not Resuscitate. Many facilities may have a do not hospitalize (DNH). I haven't seen that in every facility I've worked at, but some have that form.

If a patient becomes short of breath and becomes very anxious, they have the option to have sedation to bring down that anxiety level. These are things that can be done to make a patient’s days peaceful and give them a really nice calming environment.

Concerns with ANH

We discussed concerns with ANH already but, again, informed consent for PEG is routinely poor. We know that the ethical burden for providing only beneficial care lies with both the doctor ordering the tube and the doctor who is placing the tube. There's a lot of anecdotal evidence that suggests patients' families were pressured into placing a PEG, and then they regretted it. I've actually heard from numerous families in the course of my career that they regret the decision, but they were made to feel really bad about it. So, they went along with it and it didn't go well for them.

A study was conducted in a large community teaching hospital looking at adequate discussion of the PEG, benefits and burdens, as well as alternate approaches. It was found that these discussions occurred in about 0.6% of placements, which are not good numbers.

An international study was recently conducted in 2019 looking at placing a PEG in dementia patients. When we look at the doctors' perspectives in that survey, 60% of physicians felt the PEG actually improved the quality of life in advanced dementia patients because it prolonged their survival and improved their nutrition. Sixty-two percent of the doctors felt they were driving that decision for placement where 30% felt the surrogate or the family was pushing for it. Forty percent of doctors surveyed indicated that the PEG was placed despite their advice against it.

We know that there is a high mortality rate (i.e., 30-day mortality rate) with PEG placement. Even given that information, the survey found that doctors were still looking at PEG as just a benign procedure. That it wasn't a big deal at all.

There's a bioethics research institute called the Hastings Center that has a lot of free resources on their website (www.thehastingscenter.org). Their belief is that our first obligation is to the patient, to respect their choices or the choices of the surrogate. However, we have to be really careful if somebody doesn't like our recommendations. We don't want to drop them from our caseload too quickly because then they would have a case for patient abandonment. We must provide the education. Then, if we feel strongly that we can't be ethically involved in this case, we transfer their care to someone else. But we can't abandon our patients.

Everybody has the “right” to aspirate. If a patient chooses to go against ANH, then we need to look at how to minimize the potential aspiration event. We need to look at strategies, precautions, educate, and make sure they've got that information. Then we need to document that. Many times, we do those things, and it never makes it into the charts. So, it looks like we didn't do it.

Care Planning/Advance Directives

Many times, the patient is not in a condition where they can really make the best choice or identify the treatment option that is most appropriate for them. So again, we need to make sure we're educating. We're talking about options, the benefits, and the burdens. If the patient hasn't had that conversation with their doctor, they may not know how the disease progresses. They may not know the treatment options. I've been in situations where only one option was presented. They need to know all of their options, especially what happens if they receive treatment? What happens if they don't?

Many times, when you are asking people what's important to them, they can't answer very clearly. There is a Values History Form (https://hscethics.unm.edu/common/pdf/values-history.pdf) available that asks different types of questions. These things need to be written down. Sometimes we think we know what we want, but until we are forced to write out what’s important to us, we really don’t know.

There is also the "Ottawa Personal Decision Guide" (https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/decguide.html) that is a free download. Additionally, many states have forms that assist in identifying what's important. By doing this, the patient is identifying personal key factors and we need to back out, as far as our values and culture. If they don't like the management plan and don’t want to accept it, then we need to talk about the benefits and the burdens and document the refusal.

If the patient is decisional, then they have every right to make the choices. Sometimes patients are misinformed or misunderstood. If you provide the education at an easy-to-understand level, they can get a better idea of what you are explaining and may change their mind. We can educate them about options, and then support them if they choose to refuse.

Advance Directives Are Less Successful Because…

Sometimes advance directives aren't successful because we are talking about what are your legal rights. We're not talking about quality of life, goals, and values.

A particular study suggested using seventh to eighth-grade language to discuss life-sustaining treatments and advance directives/forms. Fifth-grade language should be used for reading material. Sometimes patients/families don't know what the terms mean. If somebody says, "Well, I don't want to be a vegetable,” we need to make this more meaningful to them and give them scenarios so they understand what we're talking about.

Additionally, sometimes our patients may not recognize that just because they wrote out an advance directive, doesn't mean they can't change it. When we make advance directives for healthy individuals, they may feel one way about certain procedures, etc. But when something happens, it may not sound like a bad idea anymore.

You can go back and change those as long as you're decisional. You can go back and start over as many times as you want. But you need to make sure that you're decisional. The only question that facilities are required to ask is, “Do you have an advance directive?”

Medical Directive versus Living Will

With a medical directive, you don't have to be ill. You are just addressing different scenarios and situations, what you want, what you don't want, etc. This is different than a living will. There are pros and cons to doing one versus the other. With a living will, in many states, you have to be terminally ill to do that. Whereas a medical directive is not a situation of life or death.

There are assessments that you may find in your patient's chart or you may be asked to provide, such as the Mini-Mental Status Exam, Brief Cognitive Assessment, the SLUMS, the Brief Cognitive Status Exam, or the Montreal Cognitive Assessment. The purpose of the cognitive assessment for our patients is:

- Relevant for memory, attention, language

- Know how pt. makes decisions

- Reasoning

- Ability to understand consequences

- No substitute for critical observation of this process

- Clinicians who observe & interact w/ pt. day-to-day

- Better positioned to evaluate quality & consistency of pt.'s decision-making ability

Informed Consent and Refusal

We want to make sure that we're documenting if there was informed consent or informed refusal. Again, what is the patient’s decisional capacity? They have to have that capacity, and we have to document that the patient agreed or the patient refused.

Standards of Decision Making

If the patient hasn't completed any documents and now there's a crisis, there are standards of decision-making. One standard is called prior explicit articulation. This means you've heard the individual talk about what they want and what they don't want, they just never did the paperwork. For example, you've heard them say, “This is what I would want or not want.”

The second standard is substituted judgment. Meaning, knowing about their previous decisions, their values, and their beliefs, you believe this is what the person would want in this situation.

The third standard is best interest. What would a reasonable person want given this particular situation? The more decision-making that can be done ahead of time, obviously the better.

POLST - Portable Medical Orders

Portable Medical Orders (POLST; www.polst.org) has different names depending on the state. You may see it as MOLST, MOST, HOLST, POST. Interestingly, this form has to be on specific-colored paper. For example, in Hawaii, the form is bright green, and in Pennsylvania, it’s bright pink. These forms must be accessible so that if there is an emergency, the EMS can find them easily. It’s recommended to tape it on the back of the front door, the refrigerator, or the medicine cabinet. It indicates what the person wants, what their plan is, and it travels with them.

This is the Out of Hospital medical orders so that anytime there is a crisis, this form indicates how the person wishes to be treated and the care plan that they want to have followed.

Another resource is Five Wishes (www.agingwithdignity.org). An organization worked with Mother Teresa and as a result of working with her, they came up with this Five Wishes document. It's in 29 languages, in braille, and meets the legal requirements for advance directives in 44 states. It can be used in all 50, but in those states where it's not a standalone form, you may have to add additional paperwork. If you go to their website, there is a link to check each state.

Adults can simply put their wishes in writing. They also have forms for children. If you're under the age of 18, the parent or the guardian has the legal right to make that healthcare decision, but at least the child or adolescent is able to make their wishes known as well so that people can consider that.

There's another resource called, Let Me Decide (www.letmedecide.org) that has online education, videos, and implementation guides. This is a beneficial resource that allows the patient to list what an unacceptable level of functioning is. If loss of functioning is not acceptable and not reversible, what does the patient want to have done versus if the loss of functioning is acceptable and could be reversible, what does the patient want to have done? So, different options can be listed out there.

Resources

Here is a list of resources:

- The Conversation Project

- National Healthcare Decision Day website

- Empath Choices for Care

- Project G.R.A.C.E.

- A Process for Care Planning for Resident Choice - atomalliance.org/download/a-process-for-care-planning-resident-choice

- Hard Choices for Loving People

- Handbook for Mortals

- Making Choices –

- Long-Term Feeding Tube Placement in Elderly Patients

- https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/docs/Tube_Feeding_DA/PDF/TubeFeeding.pdf

When looking at the forms in your state, or making your own forms in some states, there's a bit of wiggle room. You may say, “These are my choices. This is what I want and what I don't want.” But there is a clause that says I am giving my healthcare proxy the ability to take a look at the situation, look at all the facts, and decide based on the benefits and the burdens at that time. So, there is a little bit of wiggle room that your surrogate could act differently than what you have put in your form.

Benefits versus Burdens

We must consider benefits and burdens. If the scales are tipped, and there is a lot of bad versus just a little good, why are we even talking about that as an option? If there's a lot of good and just a little bit of bad, then that may be something we want to present as an option. However, we know that a lot of our individuals, even if there's a lot of bad, because of their culture, their religion, or other beliefs that's the way they want to go. Again, we're educating, we're giving them all the information that they need and they make their choice. Whether it's the patient who is decisional or the healthcare proxy.

We want to make sure that we're giving this information to this patient at the appropriate time. Is it the decision right for this particular patient? Again, look at their scenario at this particular time in their healthcare. It’s suggested to maybe reevaluate this on a daily basis or sometimes even an hourly basis when things change very drastically. Do you want to rethink if we are sacrificing the patient's right to make their decision because of the distress it might cause the family or the professional? If the patient has the capacity and they are in control, even though we may not like their choice, we want to make sure that we have ongoing communication. We are providing the information and making it easy for them to understand the terminology.

We are providing support and working toward a successful outcome regardless of the course of action taken, whether we agree with it or not.

Key Points

Again, the key points are that every patient comes with their own set of circumstances, values, beliefs, religious convictions, etc. We need to consider all of that. Advance directives are very helpful for patients and individuals who are healthy to make their wishes known. Those ADs only kick in when a patient is not able to communicate what their wishes are, and that's why we have the healthcare proxies that will stand up for us.

Many times, we can't express what's important and what's not important. So that Values History Form is very valuable to think through these considerations and write our wishes down. We need to be sensitive to everybody's beliefs and cultures and know that they are a part of that decision-making process. We may not agree with it, but that is their decision, once they've looked at all of the information.

Resources

Just to review, the Values History Form looks at the patient’s attitude towards life, health, and relationships. What their thoughts are about independence and being self-sufficient, their religious background and beliefs, relationships that they have with their caregivers and their doctors, living environment concerns, and their thoughts about dying.

Simply Put is a guide for creating easy-to-read materials. There is also the PEACE brochure that is a checklist. There are PDF files for physicians, "Improving your End-of-Life Care Practice," and also for the patients. These would be very helpful to print and have them available for patients and families: Living With a Serious Illness: Talking with your Doctor When the Future is Uncertain, How to Talk to Your Doctor When You Have Pain at the End-of-Life, and Making Medical Decisions for a Loved One at the End-of-Life.

Here is some additional information on the POLST:

- Previously stood for “Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment”

- New governance in 2017 – headquartered in DC but run by states – forms may be different colors – PA is bright pink, Hawaii is bright green

- Keep form on refrigerator door, back of the front door, medicine cabinet – where EMS will look for it

- Different names in different states – MOLST, MOST, DMOST, POLST, POST, IPOST, TPOPP, LaPOST, MI-POST, OkPOLST, PAPOLST, COLST, WyoPOLST

- Signed by health care provider and yourself

- For those seriously ill or have advanced frailty

- Out of Hospital medical orders – travel with you

- Tells ALL health care providers during a medical emergency what you want

- Take me to the hospital or I want to stay here

- Attempt CPR or NO

- Medical treatments I want – covers feeding tubes; video presentation

- This is the care plan I want followed

- SEE RESOURCES FOR MORE INCLUDING COVID INFO

Advance Directive vs. POLST (https://polst.org/advance-directives/) - Remember, the POLST is a medical order and advance directive is a legal document. The POLST website (www.polst.org) has resources for COVID: 3 Things You Can Do Now, Proactive Planning for COVID-19, and COVID-19 & You – Be Prepared: Take Control

Here is some additional information on Five Wishes, “ Treatment I want/don’t want” Scenarios:

- If close to death…

- Permanent/Severe Brain Damage, no expectations to recover…

- In coma, not expected to wake up or recover…

- Other Conditions Under Which I do not wish to be kept alive…

- Must identify conditions

- Want life support or ANH

- Don’t want life support or ANH – if it was started, stop!

- Want life support or ANH if dr believes it can help BUT stop if not helping condition or symptoms

The Conversation Project (www.theconversationproject.org) is another way to start discussions with patients and they have a lot of information on COVID-19 as well, different scenarios for families to look at.

- Help people share their wishes for care through end-of-life

- Scenarios - How to Talk to Your Doctor:

- My health care provider doesn’t want to talk about it

- I’m a health care proxy for a loved one & disagree w/ their wishes OR

- Siblings disagree w/ parents expressed wishes OR

- Dr. doesn’t agree w/ my choices & has their own strong opinion

- Being Prepared in the Time of COVID-19

- What Matters to Me Workbook

- Conversation Starter Kit- end of life care

- Choosing/Being a Health Care Proxy

- Alzheimer’s/Dementia Starter Kit

- How to Talk to Your Doctor

- Pediatric Starter Kit

National Healthcare Decisions Day website (www.nhdd.org) has a lot of links:

- Conversation Project

- COVID-19 Resources

- State Specific Resources

- AARP End of Life Planning

- MyDirectives.com

- Five Wishes – Aging with Dignity

- American Hospital Assoc. – advance care planning resources/Put it in Writing brochure

- American Bar Assoc. Advance Care Planning Toolkit

- Am. Society of Clinical Oncology & Cancer.net – advance care planning workbook

- My Living Voice

- National Elder Law Foundation – Certified Elder Care Law Attorneys directory

- POLST

- PREPARE – interactive website to navigate medical decision making

- Cake – interactive end of life planning website

- CaringInfo.com – National Hospice and Palliative Care Org; free state-specific advance directives

- DeathWise – trained coaches; free state-specific advance directives

- Engage with Grace

- Everplans – create plan, checklists. free state-specific advance directives

- Go Wish Cards

- Hello Game

- LastingMatters

- Lifecare Advance Directives

- Making your Wishes Known

- MedicAlert Foundation – option to store advance directives

- National Resource Center on Psychiatric Advance Directives

- Samada – legal guidelines, info on end-of-life care

Other resources include:

- Empath Choices for Care - www.empathchoicesforcare.org

- Print living will – English & Spanish

- Health Care Surrogate

- Jewish Resources

- Health Care Decisions on Dying

- Organ Donation

- Living Will

- Planning Toolkit

- Dementia Resources

- Healthcare Surrogate

- Project G.R.A.C.E

- www.alwr.com

- America Living Will Registry

- State forms

- Store surrogate designations and living wills in database

Additional Website:

- www.capc.org = Center to Advance Palliative Care

- geripal.com – geriatric and palliative care blog

- www.medscape.com – March 2012 issue on oncology – special report on palliative care

- www.medscape.com – August 20, 2012 Special Report - Tough talks from Medscape Oncology

- How and why to talk to the dying pt

- How to have difficult conversations with pts, families

- Psychosocial needs matter most at end of life

- 5 (incorrect) reasons oncologists avoid bad news talks

"Hard Choices for Loving People" has a chapter that you can read online. A lot of the hospice organizations in my area provide this to families when they come in for the interview and the consultation. It is great information that is easy to understand and talks about the individual who has dementia and the feeding tubes.

"Handbook for Mortals" can be found on Amazon. It is much more detailed but does give some additional information on advanced dementia and strategies.

The Resident’s Choice, located in the supplemental handouts, is a template that you can go through with a patient who may not be happy with their recommendations for diets, liquids, MPO. It takes you through all of the discussions and meetings that you need to have and the documentation. If there is ever an audit, it's very clear that you did your due diligence in offering as much as you could to the patient. You can document that you did the education. Since waivers don't hold up in courts, this is going to be very beneficial for you.

Questions and Answers

(Comment) There's a movie on Netflix called, "The Farewell" and it's about the Chinese culture and hiding the fact that somebody is dying. It's based on a podcast from this American Life.

In your experience, are advance directives revised frequently as health declines?

My experience is no. I think a lot of people feel once you've said it, you can't go back and change it. So as things change, we need to make sure the individual knows you can go back and revise those any time, as long as you are still competent.

Where can I find the template for the patient refusing NPO versus our recommendation?

I would recommend that you go to the Rothschild, the Resident Choice. That's going to give you everything that you need to follow, who to talk to, what to document. It's clear that waivers really aren't a great idea, but that Rothschild, Resident Choice is going to give you everything that you need. The Rothschild link is on that second handout.

We were talking about NG tubes and I just want to mention that I prefer to do the modified with the NG tube removed but a lot of physicians don't like that. There was a study done, and I believe the source is in that second handout just mentioned, where they looked at a modified with the NG tube in, then they took it out, waited five hours, and did the modified again. It was a completely different swallow. It was much better. So, they're recommending that you remove the NG tube for a period of time. They were looking at a five-hour timeframe. But that way, the patient gets the feel and can acclimate to the change and have a much better swallow.

Citation

Dougherty, D. (2021). Decision Making for Alternate Nutrition and Hydration - Part 1. SpeechPathology.com, Article 20434. Available from www.speechpathology.com