Editor’s Note: This text is a transcript of the course, Collaborative Therapy Isn't Pushy, presented by Marva Mount, MA, CCC-SLP.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Explain at least three collaborative therapy models.

- Describe at least three therapy ideas that can be utilized in a collaborative therapy model.

- Identify at least two data collection methods that are conducive to a collaborative therapy model.

I'm glad that you are joining me to talk about collaborative therapy. I know it is a hot topic and has been a hot topic for a while. Hopefully, I can address some things that will make you feel more comfortable about doing collaborative therapy outside of your therapy room.

What Does the Law Tell Us?

What does the law tell us about our responsibilities as speech-language pathologists, particularly in the public schools? How do those laws affect us and the services that we provide? IDEA 2004 requires that public schools, districts, and charters serve students with disabilities with their nondisabled peers to the maximum extent appropriate. The push is that we really try to meet these students where they spend most of their time and obviously that is in their classroom setting.

The law states that schools must ensure that a student with a disability is removed from the general education environment only when the nature or severity of the student's disability is such that he/she cannot be educated in general education classes. That language is very important because if you read the letter of that law, it does suggest that we need to be meeting the needs of students within their classroom with their regular education peers as much as possible unless there is something about that disability that would prevent us from going in there and meeting their needs in their classroom.

The Individuals with Disability Act of 2008 provides a greater emphasis on Least Restrictive Environment and encourages the adoption of new approaches that promise better student outcomes. Isn't that what we're all in this for? We want better student outcomes. We want our students to be successful.

What Does ASHA Tell Us?

Since ASHA is our national organization and they give a lot of guidance in terms of our areas of practice and our scope of practice, it's always important for us to look to see what they say about these matters. They talk about the treatment of speech disorders being a dynamic process, and that services should change over time as the needs of the students change. This is very important to us as SLPs serving students in the public school because sometimes we get so comfortable in our little rooms and our little areas of expertise that we forget that we need to evolve with the student. We forget that we need to try more dynamic processes and approaches with students as their needs change. Being a school-based SLP for the majority of my career, I understand how difficult that is to do. I'm not making light of that in terms of all the things that go along with our jobs. So, I want to talk about some subtleties that we can do, some subtle changes that we can make to help meet our students where they need us the most.

Why Collaborative Therapy

Why should we do collaborative therapy? Why is it so important that I get out of my room? Why is it so important that I get down to the children's classrooms and figure out what's going on there? First and foremost, we need to do these things because we can coordinate our services much better if we know what the whole team is doing. We can also learn a lot from our colleagues who are classroom teachers. They are the experts on curriculum. They are the experts on how children synthesize information within a classroom setting. They're very well versed in what the benchmarks and statewide assessments look like. They're the experts in those areas.

Since we are not the experts in curriculum, it's very important that we learn from our teachers and professional colleagues how things actually function academically. It's also a legal requirement because they are saying that there should be a greater emphasis on Least Restrictive Environment. Probably the most restrictive environment is when we remove a child from a general ed classroom and take them to our speech pathology room. That would be considered a very strict environment versus least restrictive.

We also have to make sure that we are always cognizant of what is going on around us and what the expectations are in the school for a student. Obviously, we all want improved intervention outcomes for students. Those of us who work in the schools don't do it because it's an easy job. It's probably the most difficult job that anyone would ever do. I have colleagues who are SLPs who have given it a try and said, "Forget it, I'm never doing that. That's the hardest job I've ever done. That's the hardest I've ever worked." If you are taking this course, you are very knowledgeable of how difficult the job is, and you're not doing it for fame and fortune. You're really doing it so that those children can be academically successful and then move onto an aspect of their lives, whether that be trade school, college, or getting a job. What we do is so important for children in order to be prepared for those activities as they leave school systems.

While focusing on individual needs of each student, our IEP goals, objectives, and benchmarks, we should always allow for access to the general education curriculum as well as support active participation in grade level curriculum whenever possible. Children learn best in the environment that they spend the most time in and they learn best in an activity where they can generalize skills taught. They also learn a great deal from each other, sometimes probably far more than they learn from us. So, it's really important that they have activities designed so that they can be with their same age regular education peers, who can sometimes explain things better than we can. We definitely need to take advantage of those activities that we can do in the classroom with same age peers.

When our services are integrated, we allow children to work on social relationships. They're allowed to have social interaction with same age peers. Some of our children are great at interacting with adults because that's all they ever interact with. They interact with their parents at home, then they come to school and they interact with special education teachers or in a very small group with an SLP. Unless they have pragmatic goals or objectives, we don't always work on that pragmatic, social piece. Now more than ever with children having tablets and phones and devices in their faces 24/7, they really have lost the ability to socialize and be interactive with each other.

We also need to take that into account when we're planning our therapy activities. Do students have opportunities to interact with people or other students who are the same age as them, as well as students who don't have speech and language problems? Are the strategies that we suggest making a difference or are they even feasible? We give teachers a lot of information but we never really take into account if our strategies are possible in the classroom based on all of the other tasks the teacher has to do. If we are in the classroom with the teachers, we have a bird's eye view of those suggested strategies and we can make adjustments to those strategies.

We can also focus on skills that will be immediately useful to the student. Typically, our children who have a language impairment don't generalize well, as we know. They have a difficult time taking a skill that's softly taught and generalizing it into other areas. If they could generalize, typically they would not be identified as our students. So, a skill that we teach can be immediately useful to a student but only if they're able to generalize that skill into other academic areas and away from us.

Collaborative Services

When we look at collaborative services, the number one thing that collaborative services do is support cohesive IEP goal and objective writing. This helps the team to be on the same page rather than going in separate directions to do what we think is correct for the student. We have the ability to see exactly how those children are impacted academically.

We can offer students the benefit of a variety of teaching methods, strategies, resources, and supports. We bring an incredible amount of knowledge to that classroom-based situation. The teacher brings an incredible amount of knowledge too, but it may not be the exact same knowledge and therefore children can benefit from all of us working together.

We can provide instruction at grade level rather than trying to decide if the narratives that we're working on are age-appropriate or if what we're reading with our students is age-appropriate and at grade level. If you're in the classroom, you definitely know that the materials that you are utilizing are at grade level.

We can align our goals with the academic standards and, as we know, children who are in these classrooms are obligated to learn, show and demonstrate progress on those academic standards. We, as SLPs, may not know what all those academic standards are. But, if you're in the classroom, you get a bird's eye view of that as well.

We're able to use educational materials that are familiar with the student. It is much better for the student to utilize materials that they always use versus some material that we might pull off of our shelf or might buy off of an educational website.

Collaborative services allow us to provide more appropriate scaffolding and accommodations. We want to make sure that the accommodations we suggest are actually helping the student to get better and advance more quickly through the educational activities in the classroom. We don’t want some of our suggested accommodations to hinder that process. If we aren’t in the classroom to observe, then we don't know those factors.

Finally, collaborative services help us to facilitate professional growth and development of staff. We can become a “teacher of teachers” in a way that doesn't sound pompous or overbearing or suggesting that the teacher doesn’t know what they are doing. When you are in the classroom and able to observe each other, you can do things that you see the teacher utilizing that are very useful and she can do the same.

Obstacles for Students When We Pull Them Out of Class

What are some of the obstacles for our students when we pull them out of class? The number one thing that we've already touched on is that we're working on student identified challenges in isolation. As we discussed, our children don't do a great job of generalizing those skills back to a classroom. So, we definitely need to provide more inclusion and less isolation when we're working on identified challenges with students.

We have a plethora of materials in the educational setting. We don't always have that luxury if we go into a school that has very limited speech and language materials for us to utilize. This is a perfect example of how you can get materials that are appropriate for your students and you don't have to buy them. We all know how expensive they are to purchase.

Additionally, we hope the skills we teach will be generalized into the educational setting but we don't know that for certain. As an example, I know you've been to IEP meetings where you read your goals, the progress on those goals, and you talk about how wonderful that child is doing. You discuss multiple-meaning words and inferencing and narrative development. Then you realize when you look up from your paperwork that there's a group of people staring back at you like, “Who are you talking about? That child does not do any of that in my classroom.” Sometimes that's because we teach it in a way in which the child can understand it and pick it up and maybe the teacher doesn't have those same skills and strategies. It gives us an opportunity to teach each other without having to call each other out on those things.

Pros of Collaborative Practice

We have discussed a few of the pros already: generalization, carryover, consistent student progress over time, numerous opportunities for us to train staff on differentiated instruction. I don't think many teachers got that in their college prep work or in their classes. Differentiating instruction is something that we know a lot about. So that's a great way that we can actually assist because teachers may not know what we mean by differentiating instruction or maybe they only know one way to differentiate.

Other pros include using a variety of learning modalities, we can add to a teacher’s resource library, allow for team-building opportunities, gain valuable knowledge of the curriculum, and allows us to educate and demonstrate the value of what we do. That's so important because you want your administrators in your building to understand that you're there as a team to promote educational performance for all students. What better way to do that than to be in the classrooms working with classroom teachers? The schools can actually understand and learn what we do. We are not just a person that sits in a little closet down the hallway and works on how to say /s/ and /r/. Sadly, even in today's educational environment, that is still what some people believe that we do. So, we need to give them opportunities to see what we can do in terms of the overall development of their classrooms or their ability to teach children who might not be learning the normal way or is not on the normal track for learning.

Cons of Collaborative Practice

Traditional data collection methods don't always work well for us in these large classroom-based environments. It may take us out of our comfort zone a little bit. We're very comfortable doing what we do in our environment, and we may not be very comfortable doing what we do in a classroom environment.

We may have difficulty engaging and encouraging teachers to participate in this type of a service delivery. Largely, that's because those teachers don't understand what we're trying to do. We need to do a much better job in terms of communication with those teachers and let them know that we are not there to watch them. We are not there because we don’t think the teacher knows how to teach. We are there because we bring some additional skills to the table and think that might help some students who are struggling. It's all in the way we communicate that to our peers.

Significant networking may be necessary to obtain buy-in from some teachers. Parents may be initially skeptical (i.e., “What do you mean he's not going to get special ed service. His IEP says he's going to get a special ed service.”) Parents may think that we're trying to take something away versus enrich other areas. So, it definitely comes down to the way we communicate our intentions in those situations.

We may feel uncomfortable with the role of “teaching teachers”, particularly if we're newer to the field. I don't think you want to walk up to a teacher and say, "Listen, I don't think Johnny's doing well in your class because of XYZ. I'm going to need you to step up your game in terms of using all modalities. He's not an auditory learner so you're going to have to include some visual cues or some tactile cues.” You may not feel comfortable doing that. Quite honestly, the teacher may not feel comfortable with you doing that. So, we need to learn to communicate what we do in different ways. Sometimes the best way to do that is to demonstrate our knowledge and skills where others can see it.

Collaborative Service Delivery Types

Let's talk about some collaborative service deliveries. ASHA has some position papers on the roles and responsibilities of speech-language pathologists working within the public-school setting. They also have a position paper or supportive documentation on various types of collaborative interventions.

Supportive Teaching

One type is supportive teaching. Supportive teaching is a combination of collaborative and direct teaching within the classroom. We as the SLP might teach information related to the curriculum while addressing specific IEP goals for a particular student in the classroom. Then, we might pre-teach a specific targeted skill one-on-one in a small group. So, we might start out by presenting an informational kind of teaching lesson to the class, and then we may also do some pre-teaching or post-teaching of a targeted skill to a smaller group of students, who are typically identified as speech and language impaired.

We can also teach targeted skills to an entire class with assistance from the teacher and vice versa. The teacher might be presenting the targeted skill to the entire class. We might be the one providing assistance to the teacher in that lesson. But the cycle is repeated until the targeted skills are mastered.

We continue with full group classroom instruction, then some peer-to-peer or interventionist-to-student activities in a smaller group. But this is all occurring within the same classroom environment. We're not taking the children from that environment. The SLP and the teacher work together to determine skills to address. We discuss and address the skills of our students in that classroom who have been identified as speech and language impaired. The teacher may say, “Yea, they are struggling but then this whole part of the class is struggling as well.” So, the teacher and the SLP work together to determine what skills to address within that lesson based on what the teacher knows about her classroom and based on what we know about those identified speech and language impaired students.

The SLP and the teacher are also going to work jointly on lesson planning and materials. Both of us are going to take data on the students that are identified as speech and language impaired. I know the first thing that comes to mind for every school-based SLP is, “When in the world am I supposed to have time to do that? I don't even have time to go to the bathroom usually. When do you think I'm going to have time to do this collaborative lesson planning and coming up with materials for the teacher?” But, if we don't plan those lessons, typically what happens is we go into that classroom to assist and then we feel like we're just there as a tutor or we're there to sit by a specific student and guide them through the lesson. That's because we've entered into a situation where we have no knowledge of the lesson that's being presented and we have no knowledge of the areas of focus for that teacher during that particular lesson. So, we really need to learn about what the teacher plans to do and what he/she plans to present before we can be of great assistance to the students in the class. If we are going to do some type of collaborative situation, planning is critical. I will discuss this in more detail later.

Complimentary Teaching

Complimentary teaching is when the SLP goes into the classroom as a tutor and the teacher is the primary instructor. The teacher is presenting the curriculum content for the class that day and we are going to assist specific students with work completion. I typically suggest complimentary teaching to be used at the end of a book chapter or at the end of a specific lesson that's been taught for a period of days or weeks.

This type of collaborative strategy works best after all of the teaching and information has been presented and everyone in the class has had an opportunity to be exposed to the lessons. When the lesson is done and the student is expected to complete a project or a worksheet or a test, that's when complimentary teaching is more beneficial because we get a chance to watch the child complete the activity. Then we can zero in on whatever situational problems he or she is having and figure out what strategies can be implemented to help the child get up to speed.

We can also target primary goals for our students with complimentary teaching, which is sometimes a problem with collaboration. It gives us an opportunity to collect data on that particular situation or that particular goal and objective. That is why I like doing complimentary teaching after the lesson has been presented to the class.

We can assist other students that are struggling in the class. As you know, depending on the content of the material, it's not only our students who are struggling. Some other students will be struggling too.

Station Teaching

Another kind of collaborative teaching strategy is station teaching. There has been a lot of research completed on benefits of station teaching. Station teaching is great because the SLP and the teacher divide the instructional material in two parts. Then the SLP and the teacher both take a set of students. When the instruction is completed in one station, the groups rotate to the other station. It allows instruction from both the SLP and the teacher during this session.

An example might be the teacher takes half the students in the classroom and the SLP takes the other half of the students. The teacher provides all of the instructional material the students need. She may explain the task, review the lesson’s vocabulary, etc. Once the teacher provides the general overview, the group goes to the SLP for more in-depth discussion that includes strategies, modifications, etc.

Station teaching is great because we get to work with smaller groups of students. As they rotate through those groups, we get an idea of which students really understood the content versus those who are struggling with the content. Also, we all know that smaller groups are so much easier to work with as educators. I really do recommend station teaching, particularly if you haven't done much collaboration with the classroom teacher. It provides an opportunity to plan with the teacher and ensure that both of us are on the same page in terms of what the lesson is going to entail for that day.

Station teaching also gives an up-close visual of our speech and language students and what they didn't understand from the instructional review. It can help us determine how to modify the content for a particular student in order for him or her to be successful.

This collaborative approach also allows time to overlay a student’s speech and language goals and objectives onto the classroom lesson. This helps to ensure that we are focusing on those areas that will need to be updated on the IEP.

Parallel Teaching

In parallel teaching, the students are divided in half, and the SLP and teacher instruct a designated group of students simultaneously. This differs from station teaching in that the SLP and the teacher are teaching at the same time. Both of us may be teaching the same content at the same time, it’s just for different groups of students. The great thing about this is approach is that we can teach the group that may need more modification or slower pacing because we know how to do that best. We definitely know how to modify the content, and how to modify the way we are instructing that content so that students can be successful.

Also in this approach, we may have some speech students in that group. We may also have some children that are not identified as having a speech impairment but those whom the teacher has a concern about such as students who have been in the RtI process for a while. With parallel teaching, we can observe those students closely to see if they need to be referred for special education or if they just need different strategies. It’s a great way to get to know those children who may potentially be on the fast track to needing special education.

In this particular type of teaching model, we may also be able to control some of those referrals that we get, and then when we test those students, they don’t qualify. But, we can then see these students in the classroom and make strategy and modification suggestions to the classroom teacher.

Team Teaching

Team teaching is when the SLP and the teacher teach the content together. It allows the teacher to demonstrate his or her level of expertise on the subject matter and it allows us to demonstrate our expertise in terms of modification of strategies and other learning modalities that might need to be included for particular students.

The teacher is probably going to focus more on specific curriculum content whereas we might be more intently focused on a specific area such as vocabulary development or written expression.

Team teaching is a great approach because it gives us an opportunity to bounce ideas off of each other. Once a couple of lessons are done together, you sort of get in that rhythm. In a lot of my classrooms that I go into frequently, I can predict what the teacher's about to do or say and she can do the same for me. I've learned so much from my classroom counterparts because I don't always know some of the answers to those curriculum questions. I'm not always up to date on those curriculum activities, particularly if teachers asked me to go into a math class. If I'm going into a math lesson, I need that teacher to focus on academic content. I just need to be the one to focus on why the child's not getting it the way it's being taught because I don't think anybody would want me to teach math content to anyone.

Consultation

I'm sure you are very familiar with consultation. This is where we analyze, adapt, modify, and create more appropriate instructional materials. We do a lot of this in the area of assistive technology and the AAC devices. We are working collaboratively with the teacher to determine how the student needs to function in order to progress to the next level, etc. Both the SLP and the teacher are monitoring student progress. We're monitoring the student's progress every grading period and teachers are monitoring the student's progress every grading period. We will be able to do a much better job at that together rather than trying to do it on our own.

Keys to Successful Collaboration

Commitment

Commitment is always key to a successful collaboration. We need to let go of the idea that, “This is my area and that is your area.” Let’s not be quite so territorial in terms of what we feel comfortable doing. We have to share the leadership role. We have to co-teach and co-lead and we have to be okay with that. We must learn to choose teachers who we think will be okay with that.

Our objective and primary goal is always the student. We're always looking for ways to make that student successful. If we keep that goal in mind then we can get rid of a lot of those extraneous things that happen that make people uncomfortable. We can say to the teacher, “We are both here for the benefit of this student and we're going to get the student through third grade.” By doing that, we can remove all of the other things that might happen that are of a more personal nature. We're both there working for that student, how can we do that the best way possible?

We should take advantage of learning new things from new people. I say that more from a teacher perspective because I think we, as SLPs, are constantly in the learning mode. It seems that all it takes is one case or one student for us to realize that we don’t know anything about that issue or difficulty. I think we're very in tune to learning new things and dealing with new people. I think that's what brought us all to this profession. We're good at that and we've recognized that within ourselves. But maybe teachers aren't as comfortable with that because a lot of times everything they learn typically comes from some sort of a punitive model. I think teachers are a little cold and callous to learning new things sometimes or interacting with new people because that adds a lot of stress to them in terms of what they're accustomed to. We need to remember that teachers have a hard job like us.

Team Focus

Remember to stay focused, communicate, cooperate, and demonstrate kindness and patience. This is not easy for any of us to do. But always proceed with kindness and patience. With any kind of success, whether it's ours or the teachers, praise those successes but we don't need to feel like we have to take credit for them. We want to praise all the successes we have and it doesn't matter who made those successes happen because if we work with the team, it doesn’t matter who did it.

Personalize

It’s important to be interpersonally savvy, meaning be very pragmatic. Adopt a “we” mindset versus a “me versus you” mindset. Also, establishing rules and routines within the classroom structure is very important. For example, if we're going to go into this classroom to do collaborative teaching, the teacher can't leave when we go in, right? She can’t think, "Oh, you're here, I can go take a break." No, we're here to collaborate. Collaborative therapy or collaborative interventions mean more than one person is involved. If we establish those rules and routines at the very beginning of the process, then we aren't going to get upset or frustrated. Having clear rules and routines set in the beginning is the way to go.

Efficiency

Build in adequate time for developing instruction, time for lesson planning, and time for developing and organizing materials you need. When making a schedule, we need to build in time for those things rather than thinking we will do it after hours or on the weekends. That’s great and admirable but overtime that builds resentment and can cause problems with the classroom teacher. I strongly, strongly recommend this because even if you're the sweetest person on earth and not many things bother you, I promise, eventually, this will begin to eat away at you and cause problems in relationships with your collaborative partners.

Information Sharing

We want to meet as often as we can, follow through on duties that were assigned, don't say we're going to take care of something and then don't do it. Here is a classic example, I went to a developmental class yesterday to do an activity that we had planned for the students. When I walked into the classroom, I was told, “We scrapped that because we didn't have such and such.” But they didn't communicate that with me. So now I realize, I have to improvise because we're not doing this activity anymore. It's called flexibility, right? That's what we do. It happens. But those are the types of situations that will ruin relationships over time. So, again, we want to be very free with information sharing and make sure everybody's always on the same page.

Parent Education

Parent education is very important at IEP meetings. We need to explain to parents what collaborative or integrated therapy is and why we are doing it. Explain to the parents why it's necessary. Listen to their concerns and address those concerns so that they don't feel like their child is “missing out” on special education.

We want to be united as a team. We want to be upfront and explain what our least restrictive environment (LRE) is and how important that is for their child. Again, it's all about communication. If we don't communicate those attitudes to parents that's when we run into issues with them not appreciating or understanding what we're doing.

Administrative Support

Capitalize on all teachable moments. We want to help administrators understand what we’re doing and help them understand that we're doing it for the betterment of all the students. Then, when students take statewide exams in the fall or the spring, we know that we contributed to the success of those students just like teachers do. That's going to be so important to building a relationship with the administrator and helping that administrator understand why we need a classroom, why we need to be included in budget decisions, why we need to be included in discussions about classroom makeup, and where students are at the end of the year. We can gain a lot of independence in those kinds of activities if the administration actually knows how important we are to the school.

Goal Setting

We've talked a lot about goals already. But we want to be concise in our goal-setting, define what we want to achieve, determine the strategies we need to reach those goals. Then, focus on facilitating both the quantity and quality of appropriate education for the student. Again, it's always about the student.

Curriculum: What Isn’t Language?

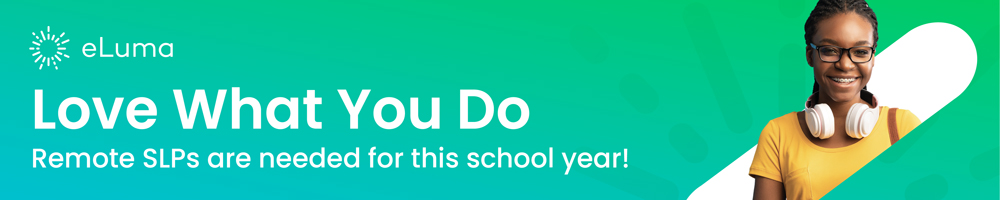

Now that we have discussed what is needed to be a collaborative partner with the classroom teacher, let's talk about curriculum. Consider the diagram below.

Figure 1. What isn’t language.

If we consider all of the things that go on in the curriculum, is there anything in that Venn diagram that really shouldn't include SLPs? Pretty much everything that happens in the classroom setting has something to do with speech and language underpinnings. Therefore, it's really important that we are available to our teachers and collaborative partners because we may have a lot of information about how all that fits together. We may understand how important language is underneath everything else they teach, but they may not understand that. As the SLP, we're the one who can complete that pathway so the teacher understands how child A is going to have to get from point B to point C through the curriculum and experience that they're having in the classroom.

We can explain to the teacher how language affects literacy, how it affects speaking and listening, how it affects comprehension, composition, etc. We are the ones who know how that all fits together.

Collaborative Lesson Ideas with a Focus on Vocabulary

Next, I’d like to discuss some lesson ideas with a focus on vocabulary in hopes of providing an idea of what collaborative lessons look like. The reason for focusing on vocabulary is because I believe that the inability to have positive experiences with new words prevents our children from advancing educationally and socially with their peers and adults. Students that we see typically have vocabulary issues if they are language impaired. So I'm focusing on vocabulary because I think we need to infuse vocabulary into everything we do, even if we don’t have a goal for it. If children don't have the words to use, they're not going to be good talkers, good writers, or good at answering questions. They won’t even understand what questions mean.

Interesting Facts

According to Hargis (1988), the average student needs to see a word between 25-45 times prior to independent recognition. Poor readers need to see a word 76 times before there's recognition and isolation. Most of our language impaired students fall into which category? Most of them are poor readers. This would suggest that the strongest action a teacher can take to ensure students have an academic background is direct instruction of terms. That means vocabulary instruction.

Vocabulary of entering first graders predicts not only word reading ability at the end of first grade (Senechal & Cornell, 1991) but also their eleventh-grade reading comprehension (Cunnigham & Stanovich, 1997). So, if we don't think vocabulary is important, we need to read a couple of those studies by Cunningham and Stanovich and Marzano. We need to read their work because that definitely puts it into perspective for how behind our language-impaired children are in terms of reading and comprehension.

Learning Pyramid

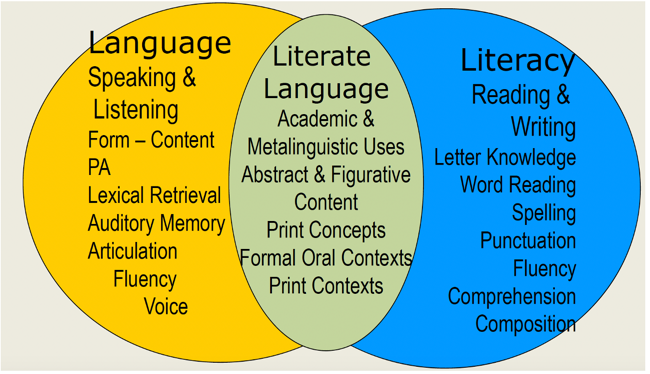

We need to look at a learning pyramid which describes what you remember most.

Figure 2. Learning pyramid.

According to the figure, we remember 10% of what we read. Twenty percent of what we hear, we remember. We remember 30% of what we see and 50% of what we hear and see. For example, watching movies, looking at an exhibit, watching a demonstration are all activities that we see and hear. Seventy percent of what we say, such as participating in a discussion or giving a talk, is remembered. This shows that a verbal component is important to remembering information. Finally, we can remember 90% of what we say and do (e.g., dramatic presentations, simulating real experiences, doing the real thing yourself).

This would suggest that last is the component that is missing in education today. We don't do a lot of “what we say and do”. We do a lot of regurgitate of what we hear. For students who are language impaired, that's not going to work. They are going to get farther and farther behind.

Three Tiers of Vocabulary and Education

In order to understand vocabulary, Judith Montgomery developed three tiers of vocabulary in education. Tier 1 includes all of the basic words that children learn such as simple nouns, verbs, adjectives, and pronouns. There are about 8000 word families in English that would appear in Tier 1. Some examples of those words are book, girl, sad, run, dog, orange. These are words that we encounter in our environment. Typically, with children who have vocabulary deficits, we focus a lot on Tier 1 words but we never move into Tier 2 or Tier 3 words which are more academic vocabulary.

Tier 2 words are those occurring across a variety of domains. There are about 7000 word families in this tier and they are the most important words for direct instruction because they're good indicators of a student's progress through school. These are words that are more academically involved. Samples of Tier 2 words are coincidence, absurd, fortunate. These words should be used across a variety of environments. They are characteristics of mature language users. This tier is made up of increased descriptive vocabulary because at this ties it's not okay just to call nouns, it's not okay just to use action words, it's not okay to just use simple nouns and action words together. Tier 2 words help to make children's vocabulary rich and that's so important for all areas of their academic success.

About 4000 words in English that fall into the Tier 3 category. Typically, Tier 3 words are very specific to a certain instance or a certain experience, like isotope, peninsula, photosynthesis. These are words that students utilize when they're talking about a particular curricular activity However, they may not necessarily carry these forward because we don't walk around talking about photosynthesis and peninsulas in daily life. We may learn what those words are or we may remember something about what that word means. But we don't carry that in our repertoire of vocabulary words because it's very instance specific.

How Do We Teach Academic Vocabulary?

There are a couple of ways that we teach academic vocabulary: defining new words, discussing new words, rereading and retelling, integrating new words into familiar context. Some of these strategies don’t necessarily happen in the classroom. So, this is where our role is important in teaching those strategies.

Vocabulary Glove

There is a vocabulary glove activity from Marilee Sprenger that I really like to use. For example, if we want a child to understand the word ‘demonstrate’, we tell the child to trace their hand on a piece of paper. On the thumb we write the definition and on each of the fingers we write words that mean the same thing as the vocabulary word. On the palm of the hand, we have the child use the word in a sentence. Once the student has learned or understood the definition of that word, we're going to come up with synonyms for that particular word. We might want to even list an antonym for the word.

I might utilize a vocabulary glove for a whole grading period and have five different vocabulary words that we're working on. This may be all that I do in those vocabulary instructional activities with students because look at how many goals I'm going to address with just this one activity. I'm working on synonyms, antonyms, grammatically correct sentences, definitions of new words. That's four vocabulary words in one activity. It’s super simple and we don't need a lot of materials. It’s very easy to implement this in a classroom with a new chapter that they are starting and we can use the words that are in that chapter.

Concept Map

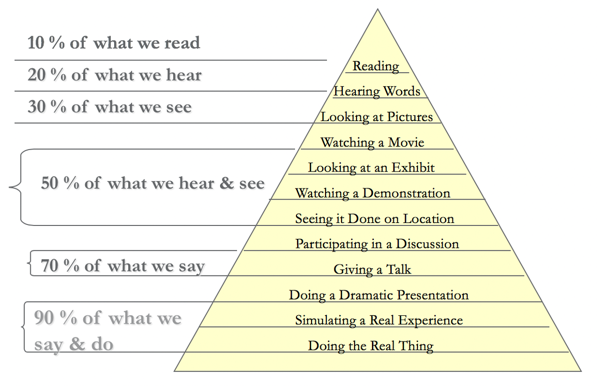

Another vocabulary activity by Sprenger is a concept map.

Figure 3. Concept map.

In this example, I used the word “determine”. You write the word at the top and then write another word in the middle that means the same thing. So, we have our vocabulary word and a synonym. Then, we might ask the student what the word means to them in simple terms, not academic terms. We will add their response to the circle on the left and on the right. This is another very concrete visual example of how to teach unknown vocabulary words in a collaborative situation in a classroom. We can do this in all those different types of teaching styles we talked about earlier. Again, we are using curriculum vocabulary and we don't need materials. Look at how much we’re going to get out of that one particular situation or lesson with a student. If I have children in a classroom that I am not collaborating in and I know that child is always struggling with vocabulary, I will share these examples with the classroom teacher so that they know how to do this.

Synonym Wheel

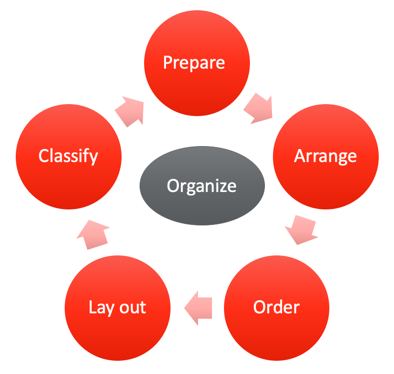

Here's another example of teaching vocabulary. Using the word “organize”, ask the student what are all the things the word “organize” can mean.

Figure 4. Synonym wheel.

If a student gives an example that's kind of off-base, but I can see what they're thinking, I will try to follow their thought process. I will put that word on the wheel as a possibility and then go back and discuss it after adding other words. Then I can go into explaining why the word they gave me is not a synonym.

Symbol wheels are another great way to teach vocabulary. We do not need any materials and we can take the curriculum words that are being utilized in the classroom. I guarantee that all the students in the class will benefit from this, not just students on our caseload. I do this with my middle school and high school students all the time because they're so visual. Once we have the diagram completed, I usually do them on index cards and clasp them together with a ring clip. Then they can take the cards with them in their backpack. If they're in the class and these words are being talked about and they don't remember what they mean, they can pull out their identification index cards and get vocabulary instruction even when I'm not present.

It’s very important for students to learn how to figure things out when we are not with them, especially in middle school and high school. We want to teach them how to do things on their own.

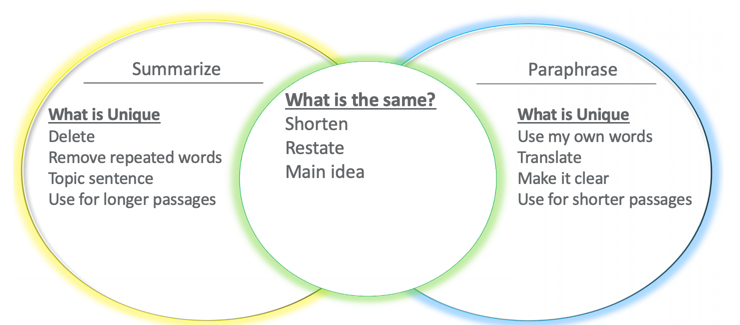

Venn Diagrams

We are all familiar with Venn diagrams. Below is an example of one using the words “summarize” and “paraphrase”.

Figure 5. Venn diagram.

What does summarize mean? What does paraphrase mean? What's the same about those words? These are 2 words that children confuse and when they take a test or standardized assessment, they may paraphrase when they're supposed to be summarizing because the words are so similar. We can teach them the differences of each of those terms and then what's similar. Then if they see either of those words in a test question, they know what they’re supposed to put on the paper.

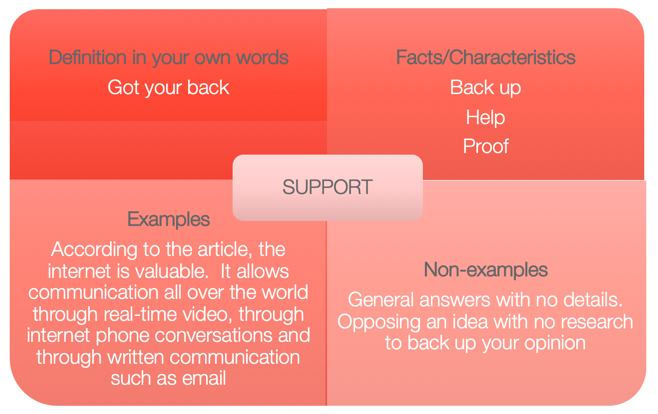

Frayer Model

Below is the Frayer Model to teach the vocabulary word “support”.

Figuire 6. Frayer model.

Primary Grade Idea

The primary grade idea I have as an example is to work on a jointly selected list of curriculum vocabulary by:

- Using thematic units

- Pair vocabulary with literature

- Whole class (large group) lesson for presentation of vocabulary to the entire class

- Circle time, snack, center time, individual seat time (small group) for additional practice/exposure to new words, specifically designed for students with a speech impairment

There are so many things we can do in the primary grades that we can't do in those upper, elementary, middle school, and high school grades. This is very important to me too in terms of how to work on vocabulary in the preschool, kindergarten, and first grade.

Teach the Vocabulary of Questions

So many of our students know the answers to questions. Jim Burke created a list of essential academic words. He has a website that has many great activities that are free. In the below list, he provides a word and then three synonyms for that word. The idea is to teach students how to advance their vocabulary through the use of words and words that are similar.

Word | Synonym | Synonym | Synonym |

Analyze | Breakdown | Deconstruct | Examine |

Argue | Claim | Persuade | Propose |

Compare/Contrast | Delineate | Differentiate | Distinguish |

Describe | Illustrate | Report | Represent |

Determine | Establish | Identify | Resolve |

Develop | Formulate | Generate | Elaborate |

Evaluate | Assess | Figure out | Gauge |

Explain | Clarify | Demonstrate | Discuss |

Imagine | Anticipate | Hypothesize | Predict |

Integrate | Combine | Incorporate | Synthesize |

Interpret | Conclude | Infer | Translate |

Organize | Analyze | Classify | Form |

Summarize | Outline | Paraphrase | Report |

Support | Cite | Justify | Maintain |

Transform | Alter | Change | Convert |

Figure 7. Big 15 by Jim Burke (2014).

Burke created this list called the “Big 15” which are words that we work on all of the time with our students. This is a great vocabulary list to start with, especially with older students in fourth grade through high school.

Sample IEP Goals

I want to give some sample IEP goals since I am frequently asked how to write goals for vocabulary.

Example goals for multiple meaning words, synonyms and antonyms:

- Given ___ words, student will name a multiple meaning word with ____% accuracy in ___ trials.

- Given ____ words, student will provide a synonym (word with same meaning) with ____% accuracy in ____ trials.

Example goal for affixes, root words:

- Given ___ words, student will determine the word meaning using affixes with ____% accuracy in _____trials.

Example goal for context cues:

- When presented with ____ sentences, student will determine a meaning of an unknown word using context clues with ____% accuracy in ____ trials.

Data! Data! Data! What Do I Need?

Let's talk about data collection. We can't just do pluses and minuses or tally marks. We have to remember why we are collecting data. Our outcome for data collection needs to be able to demonstrate progress.

We have to understand why we're taking the data. What kind of data are we trying to collect? Are we doing quantitative or qualitative? What are we trying to measure? What do we need to measure?

Frequency, how often to determine change, multiple measures, the manner of the measure, internal factors and external variables are all factors that we have to look at in collaborative lesson planning in terms of taking adequate data. Those tally marks aren't going to work. Try to think outside of the box. For example, let students take their own data. While going through all those vocabulary activities, let them assess how they think they've done. Have them color in graphs, “Today you did 20%. So, color up to 20%. The next time I come to your class, we're going to do the same activity and we're going to see how your progress is.” Students love to take their own data. It’s also very effective in terms of winning parents over for a more collaborative service model if we involve their children in their progress.

Take good data less often. We don't need to take data every time because we may be using some other types and forms. We can utilize rubrics which are great for collaborative practice. We're also going to be looking at teacher data, grades, portfolios and work samples because you were in their classroom when those things occurred. So, think about what to do outside datasheet collection.

References

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (1996). Inclusive practices for children and youths with communication disorders. Technical report. Retrieved from www.asha.org/policy/TR 1996-oo245.htm

Baxendrall, B. W. (2003). Consistent, Coherent, Creative: The three c’s of graphic organizers. Teaching Exceptional Children, 35 (3), 46-53.Campbell, Dorothy M. (1999). Portfolio and Performance Assessment in Teacher Education. Centers for Teaching and Technology. Book Library. Paper 37.

Beck, I., McKeown, M., & Kucan, L. (2002). Bringing words to life: Robust vocabulary instruc- tion. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Beck, I., & McKeown, M. (2007). Increasing young low-income children’s oral vocabulary repertoires through rich and focused instruction. The Elemen- tary School Journal, 107(3), 251-271.

Burke, Jim & Gilmore, Barry (2014). Academic moves for college and career readiness, Grades 6-12: 15 must have skills every student needs to achieve. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Capilouta, G. J. and Elksnin, L. K. (1994).Language Speech and Hearing Services in Schools. October 1994, Vol. 25, 258-267.

Cunningham, A. E. and Stanovich, K. E. (1997). Early reading acquisition and its relation to reading experience and ability 10 years later. Developmental Psychology, 89, 114-127.

Fountas, I. C. and Pinnell, G. S. (2001). Guiding Readers and Writers: Teaching Comprehension, Genre, and Content Literacy. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Fountas, I. C. and Pinnell, G. S. (2001). Guiding Readers and Writers Grades 3-6: Teaching Comprehension, Genre, and Content Literacy. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Graves, M. (2006). The vocabulary book: Learning and instruction. New York, NY: Teachers College Press. (Frayer Model)

Hargis, C. (2006). Teaching Low Achieving and Disadvantaged Students. NACADA.

Hargis, C., Terhaar-Yonkers, M., Williams, P., & Reed, M. (1988). Building Vocabulary: Repetition requirements for word recognition. Journal of Reading, 31, 320-327.

Marzano, R. J. (2004). Building background knowledge for academic achievement: Research on what works in schools. Alexandria, A: ASCD.

Marzano, Robert J. Reading Instruction: Teaching the 21st Century. Educational Leadership (2009). Vol 67, No. 1.

Montgomery, J.K. (2007). The Bridge of vocabulary. Bloomington, MN: AGS Pearson Assessments.

Mount, M. G. (2014). Facilitating Cohesive Service Delivery Through Collaboration. ASHA Special Interest Group 16 Perspectives, Vol 15, No. 1, pp 15-23.

Olswang, Lesley B. & Bain, Barbara. (1994). Data collection: Monitoring children’s treatment progress. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, September 14, 1994, 55-66.

Senechal, M. and Cornell, E. H. (1993). Vocabulary acquisition through shared reading experiences. Reading Research Quarterly, 28, 360-374.

Sprenger, Marilee (2013). Teaching the critical vocabulary of the common core: 55 words that make or break student understanding. ASCD. Alexandria, VA.

Additional Readings

Archibald, Lisa. (January 2017). SLP-educator classroom collaboration: A review to inform reason-based practice. A review to inform reason-based practice, Vol 2: 1-17. Autism and Developmental Language Impairments.

Suleman, Salima, McFarlane, Lu-Anne, Pollock, Karen E. Pollock, Schneider, Phyllis. (January 2014). Collaboration: More than “working goether”: An exploratory study, (37) (4). Canadian Journal of Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology.

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2016). Scope of practice in speech-language pathology. Available from www.asha.org/policy.

McKean, Cristina, Law, James, Laing, Karen, Maria Cockerill, Allon-Smith, Jan, McCartney, Elspeth, Forbes, Joan. ( November 2016). A qualitative case study in the social capital of co-professional collaborative co-practice for children with speech, language, and communication needs. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders.

Glover, Anna, McCormack, Jane, Smith-Tamaray. (September 2015). Collaboration between teachers and speech and language therapists: Services for primary school children with speech, language, and communication needs. Child Language and Teaching Therapy.

Wilson, Leanne, McNeill, Brigid, Gillon, Gail T. (September 2016). Inter-professional education of prospective speech-language therapists and primary school teachers through shared professional practice placements. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders.

Questions and Answers

Can you explain the concept map again and what each prong means?

You can actually make a concept map for anything you want it to do. If you are working on vocabulary, you can make your prongs for synonyms to that particular word, you can make antonyms for that particular word, you can work on negation, what is a word t