Disclosures

I am on the Professional Advisory Council of CASANA. I receive employment compensation from Mayo Clinic. I receive speaker fees and royalties from CASANA for products, revenue share from a professional development company and I am being compensated by Speechpathology.com for this course.

Introduction

In this course, I am going to focus on describing the connections between or among speaking and reading and writing. I will address intervention superficially as “food for thought” and to provide some ideas for how to pursue individualized intervention for children that you are seeing. As an aside, there is an additional handout of literacy references that are websites that I have found to be helpful in guiding my thinking as I work with children.

A question that comes up more than it should is, “Do SLPs have a role in reading and writing?” Of course we do. There's no doubt that children with apraxia and even children with simple speech and language problems are at increased risk for reading and writing issues. However, apraxia does not cause these literacy problems. We can say that because children without apraxia also have reading and writing problems, but there is an interaction of factors. So while there's a growing research base for best practices, for intervention in all of these areas of apraxia, such as reading and writing, we still need to collaborate with other professionals who can provide us with guidance and who have expertise so that we can assess a child's strengths and needs appropriately. It definitely takes a team, and SLPs certainly have a role.

ASHA’s Position Statement

ASHA states that speech-language pathologists play a critical and direct role in the development of literacy and these are implemented in collaboration with others. This is an official ASHA position statement. Our profession is so broad that it's easy to get caught up in things but we do have an ethical obligation to be competent in the areas that we serve and if we serve children with speech and language problems, particularly with CAS, we have an obligation to address literacy as well.

Risk

We know that there is a risk for later literacy difficulties because there are numerous studies that look at speech and language problems and later literacy issues. It’s important to know that there is variability in the expression of these disorders depending on factors such as the age of the child, the child’s language development and what domains are affected. These factors are important to remember as we're looking at a child’s speech development, their language development and their later literacy development.

In the past, many school districts used a discrepancy model that says a child has a history of speech and language problems. However, there isn’t a large gap between their academic skills and their measured cognitive or language skills, therefore it must not be a learning disability. Fortunately, there are more recent efforts like Response to Intervention (RTI) that look at the child's rate of progress as a determining factor for intervention. Regardless of how we identify issues with children, there is robust literature suggesting that there is a connection between early speech and language problems and later difficulties.

CAS and Risk – ASHA’s Practice Portal

ASHA’s practice portal for apraxia of speech talks about children with apraxia being at increased risk for expressive language and weakness in phonological foundations for literacy (i.e., phonological awareness skills) (Lewis, Freebairn, Hansen, Iyengar et al., 2004; McNeill, Gillon, & Dodd; 2009a). Again, these are not causal but these problems can reflect the consequences of apraxia interacting with other co-occurring problems such as attentional difficulties or learning disability. It might include the effects of compensatory strategies that need to be used to address:

- Delayed language development

- Expressive language problems such as word order confusion, grammatical errors or word finding problems

- Issues related to reading and writing and spelling

(Crary & Anderson, 1991; Davis et al., 1998; Dewey, Roy, Square-Storer, & Hayden (1988); McCabe et al., 1998; Shriberg et al., 1997)

ASHA has developed significant resources in recent years. The practice portal addresses the scope of practice related to reading and writing and apraxia and the fact that there is an interaction between apraxia, speech and language problems and reading and writing difficulties. There is a strong correlation, or a relationship, that may relate to the child's underlying ability to make use of information or may result from some specific deficits in their cognitive functioning.

Risk: Reading

Apraxia falls under the broad category of speech sound disorders. Therefore, when looking at the risk for reading, we can look at the speech sound disorder literature and assume that it applies to children with apraxia, perhaps even to a greater degree than it would for a child with a typical phonological disorder. There is typically more difficulty with language for children with apraxia. Again, we can look at language skills as they relate to reading and assume that to some extent this would apply to children with apraxia. Catts and Nelson (2017) suggest that while a child may have processing deficits, other factors are going to increase or decrease the likelihood of having a reading disorder.

Other environmental and genetic factors have to be considered, as well, for contributing to increased or decreased risk (Pennington, 2006, Catts, et al., 2017; Hayiou-Thomas, et al, 2017). Hayiou-Thomas and her colleagues found that there were some modest effects for reading difficulties with speech sound disorder alone. However, if a child has speech sound disorder and an additional problem, like language delay or disorder, the negative consequences for learning to read increase. Therefore, the more issues the child has the more risk they have for later reading or writing difficulty.

Multiple studies have found speech sound disorder as a factor, but it's probably not the strongest factor. Speech sound errors alone can be a risk factor and persistent speech sound errors increase the risk. If other factors are added in, that also multiplies the risk. So, we're looking at layers of factors occurring with these children and again, we're talking about apraxia as a more severe form of a speech sound disorder in most cases.

Risk: Written Language

Recently, I have become more interested in written language among children with apraxia or speech sound disorders. A study that we published a couple of years ago looked at children with IEPs or speech and language problems and compared them to children who didn't have an IEP or speech and language problems. This was a cohort of over 5,000 children in our local area who had services through the local school district and received their medical care through one or two large institutions in the area. We had a really rich base of both school documentation and medical documentation of the children's health and well-being and academic skills.

Our study found that for written language, the cumulative incidents (i.e., the number of children identified in their schooling from age 5-19) showed that about 61% of boys and 55% of girls who had a speech and language problem also had a written language disability that was served under an IEP. By the time these children had reached age 19 the majority of them had some kind of a written language difficulty. This is compared to only 18% of boys and 9% of girls who did not have an IEP for speech and language problems. Again, it was not causal but there was a very high correlation among children with an early history of speech and language problems and it had to have persisted to school age for them to have an IEP for speech. Once they had the IEP for speech they tended to have an IEP for written language disorder too. We didn't look at reading separately because there is already such a well-known risk for reading difficulty among children with IEPs for speech and language.

One other thing to keep in mind with this particular study is that in Minnesota, to qualify for an IEP for speech and language difficulties, you have to score two standard deviations below the mean. So these were children who were on the more severe end of speech and language problems which would likely increase that association. But when we look at children with even lesser degrees of impairment, we can extrapolate and say that a number of them are also at increased risk for reading and writing difficulties.

Connections

How are these connections built? Language, both spoken and written, is arbitrary symbols. We use letters and other languages might use pictograms. I may not understand the writing system of some other languages but the people who grew up in that system do because they were taught that arbitrary system.

Language impairment is a problem of processing information in the verbal domain of understanding and listening. Reading and writing reflect processing in the written domain. The receiving domain is sort of the language impairment part and the producing domain is the reading and writing part; but they are all language-based. If you don't have good language skills it's difficult to understand and produce language. If you don't have good language skills to produce it in written form, a new modality is also difficult because you're looking at the sound system as well as the linguistic system - the grammar and the syntax - that need to be written down using these arbitrary symbols.

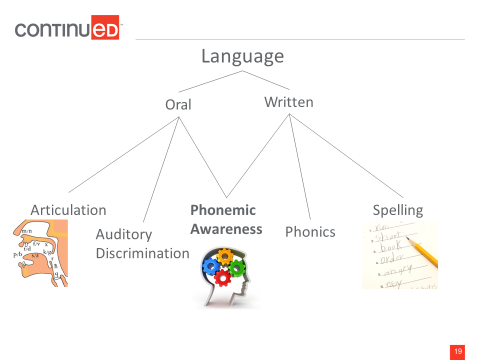

In Figure 1, language can be divided, somewhat, into separate skills.

Figure 1. Language skills.

Oral language is comprised of articulation, which encompasses phonology and apraxia. We listen to sounds, so we have to discriminate sounds and develop phonemic categories in order to discriminate words from each other. There is an overlap in phonemic awareness for oral and written language. Referring to figure 1, phonics is listed under written language, which is understanding sound patterns in written language. This correlates to auditory discrimination in oral language. Spelling is somewhat analogous to articulation because you are writing down individual letters just as you are articulating single sounds and sequencing them into words.

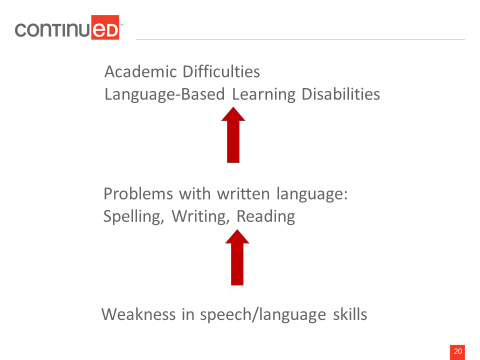

Referring to Figure 2, as we use these arbitrary symbols and children develop an understanding of the system, the first thing we may see in children is weakness in speech and language skills because children learn to speak before they learn to read and write. Before children become involved in the outside world of academics we're talking to them in the home. It's possible that there's a cascading of difficulties where we see children who have a weakness in speech and language skills, progress to some weaknesses in written language (i.e., spelling, writing and reading). Children with early weaknesses, who have some mild problems especially if they're not addressed, can cascade and have a change in diagnosis. In school, these children are given a more formal diagnosis of language-based learning disability, not because the underlying nature of the problem is different but because the demands of the academic setting are putting new demands on their language system. There are new modalities being expected of these children as they begin to acquire skills beyond oral skills.

Figure 2. Cascading of difficulties.

Connections: Reading

Reading is a language-based skill that uses visual input (Catts & Kamhi, 1999; Snowling & Stackhouse, 1996). We are taking in an understanding of those abstract symbols and processing them. We are getting meaning by viewing those symbols, but as we get that meaning, we are using three different skills: decoding, comprehension and fluency.

Decoding. Decoding is being able to take those written symbols and translate them into sounds of spoken language (i.e., sound-letter correspondence). A child may be able to decode words well without comprehension. I have had a fair number of parents come to me with children with a history of apraxia who say they have been working on reading, they know all the letters of the alphabet, and they can easily decode. But when I ask what the word means, the child doesn’t know. They know the sequence of sounds and they can sequence them but decoding does not lead to comprehension. It simply leads to the skill of sequencing the sounds.

If a child has severe apraxia, it may be difficult to assess decoding because they're unable to produce certain sounds, or the sequencing of sounds is an issue for them. So, when we're assessing children for a reading deficit and they have a history of apraxia we have to be aware that in the decoding process there could be a phonological awareness aspect where sound-letter correspondence is disrupted. However, there could also be a motoric output problem where they understand the sound system but can’t express it efficiently due to the verbal motor constraints.

Comprehension. Maybe a child can decode the word but do they understand it? Not only can they understand it, but can they interpret it so that if they read the word ‘dog’ it means all dogs not just the dog who lives at their house. They are decoding the word, the ‘d,’ the ‘o’ and the ‘g’ to make ‘dog.’ They are making connections between the word they read and their knowledge and experience. For example, “I have a dog at my house and my neighbor has a different dog but it's still a dog. I saw a pug dog at the pet shop and that looks very different than my dog but it's still a dog.” It’s understanding, interpreting and making connections. This is where the language piece comes in and some children might simplify and call every four-legged animal a dog. They think a dog or a cat or a cow could be called ‘dog’ because it's a word they can say and people are reluctant to challenge their motor system and enrich their vocabulary. We need to be conscious of those occurrences too. I've had an experience with a child who lived on a farm and they called every kind of bird on the farm a chicken. So we talked about the importance of providing the child with vocabulary such as chick, rooster, hen and duck so they understood that there was more involved and more language. We don’t want the parents to simplify the language or assume lack of competence in language when we're not providing that instruction.

Fluency. Fluency is one of the trickiest areas for children with apraxia because the child is expected to read text quickly and accurately. The child is decoding and also calling on their knowledge for sight word recognition. Fluency is a bridge between word recognition and comprehension. A fluency task is looking at whether or not the child can recognize and recall a word, and can they do it rapidly. Again, children with apraxia might have difficulty with speeded tasks, especially fluency because of motor speech constraints more so than a language difficulty, although that can play into it too.

The DIBELS is a tool used often in the schools and it has some value. But the manual specifically excludes using the fluency task for children with apraxia due to concerns about their motor impairment. That doesn't mean it should never be used, it just means that if it is used for that child we should think about how to adapt the task to measure their ability to read quickly and accurately against different points in time rather than against their peer group at that same time. So, be aware of limitations but do not be afraid to use these types of measures when they might be helpful for us. Understand a child's abilities or changes in their abilities.