Editor's Note: This text is a transcript of the course, Back to Basics: Guidelines for Management of Communication in Rett Syndrome, presented by Theresa Bartolotta, PhD, CCC-SLP.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Identify the features of Rett syndrome that impact communication.

- Describe effective strategies for assessment of communication in individuals with Rett syndrome.

- Describe strategies for assisting individuals with Rett syndrome to reach their communication potential through best practices in intervention.

Introduction

I am happy to see this great interest in Rett syndrome, which is a topic I have spent about 20 years working on. I want to begin by giving a brief overview of Rett syndrome because you most likely do not have that many people with this rare disorder on your caseload. Rett syndrome primarily occurs in females. There are males living with Rett syndrome, but because it is an X-linked chromosomal disorder, males have a more severe presentation. Due to this, many males who are diagnosed with Rett syndrome live a short amount of time and the mortality is high. Since the majority of individuals living with Rett syndrome are females, I will frequently refer to females with Rett syndrome. If you know a male with Rett syndrome, I do mean to be inclusive, but we tend to default to talking about females because it is primarily a female disorder.

Rett Syndrome

The prevalence is approximately one in 10,000 live female births worldwide. The diagnosis is clinical and is part of the clinical assessment, which is usually led by a neurologist. A genetic test is conducted to see if the person has a mutation in the MeCP2 gene on the X chromosome. It is often that the genetic mutation confirms the diagnosis. However, there are individuals with a Rett syndrome diagnosis who do not have the genetic mutation, yet still meet the clinical guidelines.

Most individuals with Rett syndrome are born after a typical pregnancy and there are no signs in the neonatal period that there is something going on. What happens is there is a period of normal development that is followed by a regression. This affects language or communication skills, and if the child is preverbal it may affect motor skills. The first regression can occur as early as the middle of their first year, but it can last until age two or three. It is common for a number of individuals who show a regression to be thought of as having autism. This is because it is common for a child with autism to experience a regression. The two have a lot of similarities in the beginning stages, but it is less likely that individuals with autism will have severe motor impairments as opposed to Rett (RTT).

Diagnostic Criteria

The diagnostic criteria were updated and revised in 2010. Before then, Rett syndrome was considered to be an autism spectrum disorder, and was listed in the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-4) under the autism spectrum umbrella. With the publication of the DSM-5 in 2013, Rett syndrome was deleted from the DSM because it is primarily caused by a genetic mutation. The diagnosis is made clinically and the mutation is confirmed through a blood test. There are typically two kinds of Rett syndrome: there is classic Rett syndrome, where someone meets all of the required criteria, and there is a less severe version called atypical or variant Rett.

Classic Rett Syndrome Main Criteria

The main criteria for classic Rett are listed below, and all four of these are required in order to meet the diagnosis of classic Rett syndrome:

- Partial or complete loss of functional hand skills.

- Partial or complete loss of spoken language skills.

- Impaired apraxic gait or absence of ability to ambulate.

- Stereotypic, repetitive, nonfunctional hand movements.

There is an early period of typical development, and then a regression will most likely begin before the third birthday and last up to two years. People can still be regressing at ages four or five, but usually there is a stabilization between ages three and five, followed by a regaining of skills. We used to think this was a degenerative disorder, but it is no longer considered to be so.

Starting with the four required criteria, there must be a partial or complete loss of functional hand skills. This means that someone with Rett syndrome is unable to engage in the hand skills that are part of daily activities. An example of this is bringing things to the mouth, which can become evident as they get older and begin using utensils. If you start to see these kinds of features, it may be classic Rett syndrome. There is also partial or complete loss of spoken language skills. Some individuals never begin to speak. Others will begin to speak within their first year, and then will usually lose most or all of their spoken words. The individuals who retain verbal skills usually meet the atypical or variant Rett and tend to have a less severe presentation. That is important to remember because most individuals with Rett syndrome are almost completely nonverbal. If a young child is on your caseload, it is important to introduce augmentative communication because it is unlikely that they are going to be able to use spoken language in a functional way.

The third criteria is impaired apraxic gait, or the complete lack of ability to ambulate. Many individuals with Rett are completely unable to stand or walk. If they are able to walk, there are balance issues. They might have a wide, apraxic-like gait, where their acquisition of motor skills is most likely delayed.

The fourth criteria is stereotypic, repetitive, non-functional hand movements. These usually look like bilateral hand movements and can take different forms. It could be hand-wringing, clasping the hands together, or doing something with one hand and something else with the other. These are not generally under the individual's volitional control, but with appropriate intervention you can get some girls to use their hands in a functional way. That is where working with occupational therapists is helpful.

Supportive Criteria

Along with the required main criteria, there are supportive criteria. They can be observed but are not required. These are conditions that frequently accompany Rett syndrome:

- Respiratory disturbances, such as rapid breathing or breath holding

- Teeth grinding

- Impaired sleep patterns; frequent sleeping during the day, frequent night waking

- Abnormal muscle tone

- Peripheral vasomotor disturbances

- Scoliosis and/or kyphosis

- Growth retardation

- Small cold hand and feet

- Laughing and/or screaming spells, not appropriate for the context

- Lessened response to pain

- Intense eye communication – often referred to as “eye pointing

These are important for us to know because they affect how we assess, as well as what we use as an intervention program. It is typical to see respiratory disturbances, which can be characterized as rapid breathing or breath-holding. As speech-language pathologists, we know that this can also impact feeding. We will often see that some girls with severe breathing and oral-motor function issues have to rely on G-tubes for nutrition because they are unable to do so by their mouth. Teeth grinding is another feature, as well as impaired sleep patterns. There is a pattern of frequent sleeping during the day, accompanied by frequent night-waking. It makes it difficult for a girl to participate in educational or social activities due to fatigue. Abnormal muscle tone is common as well. They are typically hypotonic, though some girls will have hypertonia. They have peripheral vasomotor disturbances and poor circulation that is characterized by bluing of the extremities, like the hands or the feet.

Scoliosis is common and can start in late childhood or in early adolescence. Some individuals will have a quick and severe progression of the curve. Some can go from zero to 45 or 50 degrees of a curve in less than one year. Surgery is often required, which can impact their ability to ambulate or sit up, as well as regard their communication partners with good interaction. Many of them have a growth retardation and tend to be a smaller height, but that is not everyone in the syndrome since some girls are bigger. However, it is common for them to have smaller hands and feet. The peripheral vasomotor disturbances affect their circulation and typically have cold extremities. They will often engage in laughing or screaming spells that are not appropriate to the context. They are not under their volitional control, and that can affect their ability to interact in social or educational environments. They have a high pain threshold, as well as what is called eye pointing, or intense eye communication. Regardless of whether the diagnosis is more or less severe, eye gaze is almost universal across all individuals with Rett. We can use that eye gaze for interactions, and then as a potential way to assess ability once we move to augmentative communication.

Atypical RTT

With atypical Rett, the person can experience a period of regression around the middle of the first year until age five. They must have a minimum of two of the four main criteria, and five of the 11 supportive criteria. Someone who is diagnosed with atypical Rett syndrome may or may not have the mutation, but do meet the criteria and are typically less impaired than the classic case. While thinking about communication in Rett syndrome, it is important to emphasize that the early literature about Rett syndrome suggested that everyone with Rett was severely impaired and incapable of communication. This is because they were assessed as being pre-intentional and incapable of using anything in a symbolic way. Rett syndrome was described to the world until the 1960s, and the first case diagnosed in the United States was not until the 1980s.

We still find that a lot of people do not know about Rett syndrome. However, we know that once the gene was found in 1999, and the testing was used to confirm cases, the spectrum of Rett syndrome actually became more diverse. This way, people who had more abilities than others were still being diagnosed appropriately. That also shifted expectations and I believe that professionals are now more open to considering communication potential. Most of the individuals are nonverbal, and over the last few years we have seen advances in augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) technology, especially with electronic eye gaze systems. I think we have a greater understanding of individuals’ abilities with severe disorders and are now moving to embrace a model of competence. That does not mean that there is a lack of impairment, but rather a shift in thinking to more positive opportunities, as well as being more optimistic about potential for growth.

Literature on Communication is Limited

Literature about communication and Rett syndrome is still limited. In 2019, Annika Amoako and Dougal Hare published a systematic review of intervention studies on communication. All of the studies reported improvements in communication, but there were some methodological problems that plagued a lot of the studies. All of the studies had a small subject number, and it is difficult to do this while studying Rett syndrome because it is rare and tends to be a heterogeneous group. Therefore, we do not have a lot of data on communication intervention. However, I came together with Gillian Townend from the Netherlands and Helena Wandan from Sweden, who are both speech-language pathologists. We also worked with Anna Urbanowicz from Australia, who is an occupational therapist. We met at a conference in Europe and decided to see what we could do to advance awareness about communication potential in Rett syndrome. We then were recipients of a project that was funded by the International Rett Syndrome Foundation. Our goal for this project was to develop clinical guidelines for how to manage communication in Rett syndrome. We wanted to find the best practices in assessment and intervention.

Consensus-Based Guidelines

We have developed what we now call consensus-based guidelines. This is primarily because literature is limited, so we did an expansive review of English-language papers published all over the world, going back 10 years. Along with that comprehensive literature review, we surveyed parents and professionals from a total of 43 countries. We translated the surveys into 14 languages and had 650 people participate. From that, we were able to put together guidelines for assessment and intervention. We also went through a Delphi process and identified 36 experts from a variety of professional fields, such as speech-language pathology, assistive technology, special education and occupational therapy. Additionally, we took note of parents who knew a lot about individuals with Rett syndrome and were primarily presidents of parent associations. We put together guidelines for statements about communication, as well as recommendations. We have since developed a handbook to enable parents and professionals to engage in the best practices. You can go to Rettsyndrome.org and see the information that they have on communication, including the guidelines. We also have a journal article that has been accepted by the AAC journal.

Fundamentals

The potential to communicate is often underestimated in Rett syndrome. As you think about the physical issues and co-occurring medical issues, you can understand that these individuals are struggling with their bodies on a daily basis. Communication is hard for them, and if we do not understand the impact of those features, we can underestimate what they can do.

An important point, which is shared widely by a number of AAC professionals, is that there are no prerequisites needed for AAC. Someone should not have to demonstrate that they can function on a symbolic level in order for us to consider providing the individual with an augmentative system. Due to Rett syndrome being rare, there are a lot of people working with these individuals who have never seen one before. The individual should be supported by a multidisciplinary team that can help troubleshoot all of the issues they may present. That team should include a speech-language pathologist and outside expertise when needed, such as a lecture like this. There are also specialty clinics across the U.S. in which individuals with Rett syndrome can be supported by a team and they can get information about AAC.

Professionals Who Work with Individuals with RTT

Professionals who work with individuals with Rett syndrome should:

- Seek specialist knowledge and expertise in the area if they are inexperienced.

- Connect with the other members of the broader team who are working with the individual and family so that support and advice and recommendations are coordinated.

- Train other communication partners in communication techniques and strategies that will benefit the individual with Rett syndrome.

Professionals should seek specialist knowledge. Connect with other members of the broader team so the individual and their family are supported and there is good consideration given to their needs. This way the advice and recommendations are all coordinated and everyone is working together. A key point for those who use AAC is that it is important to train communication partners in techniques and strategies that will benefit the individual with Rett syndrome. That is something that we all should do whenever we work with someone who is not communicating verbally.

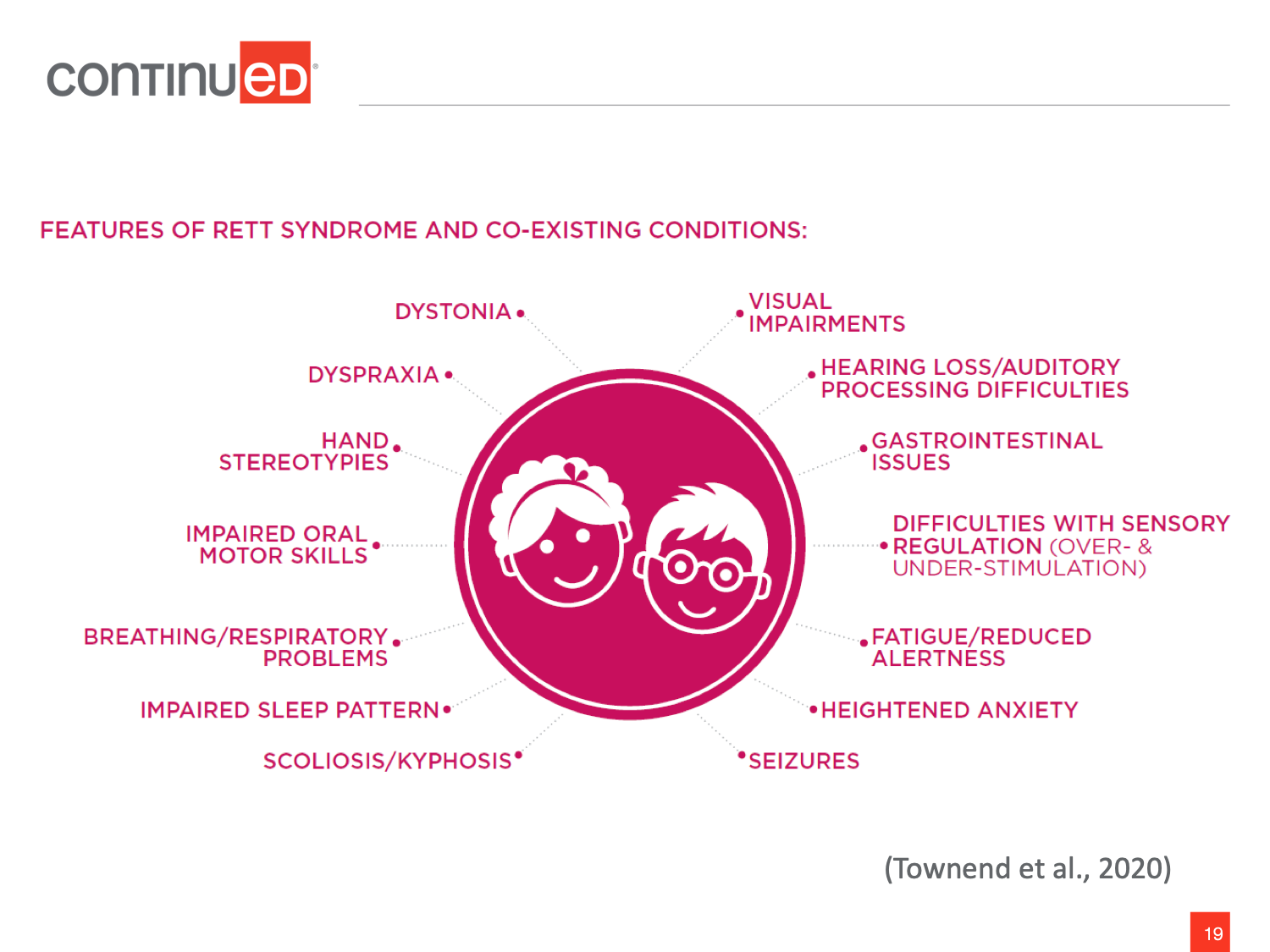

Below is an image of features of Rett syndrome and coexisting conditions that will impact communication.

Figure 1. Features of Rett syndrome and coexisting conditions.

Beginning with dystonia, it is typical for individuals with Rett syndrome to have motor issues. There may be rhythmic movements that are not under their volitional control, and it can affect their ability to use parts of their body with consistency. It is important to consider motor movements when you are planning on using augmentative communication. If someone does have dystonic movements, it may benefit you to wait until they are not moving as much in order to get a response that would be under their control. Dyspraxia is a motor-planning issue that is commonly seen in Rett syndrome. It is also common for individuals to need extended response time. This can be as few as five seconds and could go up to a minute. When you think about waiting an entire minute for someone to give a response, that is a long time. However, a communication partner who knows of the individual’s normal response time is key to the success of someone's communication development.

There are also hand stereotypies, which are repetitive, non-functional hand movements that are not under their volitional control. You may be able to stabilize one arm using a soft splint. Here is where we need our occupational therapist colleagues because if you gently help the individual gain control over those stereotypies, they may be able to access a communication device or a switch. They may also have impaired oral-motor skills. Speech is usually not a functional goal, so early interventions should not spend a lot of time on it. If someone is vocal, encourage that and their use of as many modalities as they can get under control. However, remember we want to go to AAC as early as possible.

It is important to also remember the impact of breathing problems and fatigue, as well as scoliosis on posture. It is common for them to have seizures, whether it be grand mal seizures or shorter periods of inattention. Another term you might hear is “Rett spell,” which is not necessarily a seizure. If you do see that someone does not seem to be fully cognizant, you want to talk to the members of the team to see if medication could help. There could also be heightened anxiety in a large population. This can be due to underlying physical issues and difficulties with regulation. We want to make sure that we can provide a supportive and calm environment as often as possible in order to limit the impact of that interaction.

Experiencing fatigue is when it is important to think about sensory regulation. This is because you can have someone who is over or understimulated, and this is when we can use input from our occupational therapy colleagues. In the handbook we created, we were grateful to occupational therapist Judy Lariviere who uses a traffic light system. Green represents a state of homeostasis. Somebody in a yellow phase is either mildly under or overstimulated. Somebody who is in a red phase is over or understimulated, unable to engage or almost asleep. In speaking to occupational therapists, we can get suggestions on how to move someone to a regulated state.

Gastrointestinal issues are common as well. With a lot of the girls, constipation is a problem and can have discomfort or reflux. It is also difficult to get thresholds for levels of hearing, but we are able to get gross hearing measures. This way we can get a sense of whether or not they can hear. We want to consider that they might have auditory-processing difficulties based on how they present. You want to think about presenting multimodal stimulation and providing extra time for processing. Additionally, individuals with other neurological conditions have visual impairments. You want to speak to experts about that when you plan for augmentative communication.

Strategies for Engagement

When we think about intervention and assessment, there are some strategies for engagement that we can use to maximize an individual’s potential. You want to talk directly with the individual and not talk over them. Acknowledge that they can understand you, make eye contact and use multimodal communication. Make AAC available at all times. We should be aware that not everybody has the resources for a high-tech eye gaze device, which is also not always appropriate in every situation. If someone does have one, we also want to make sure that they have access to low-tech or no-tech at other times.

We want to think about decreasing motor demands to get a response as cognitive load increases. This is because of the severe motor-planning issues. For example, you could be assessing them and present them with a device with icons. Instead of asking them to indicate a particular icon you may want to try pointing out the choices, giving them time to process, and then offer again to see if they can give you a response. We want to be aware that as we increase the cognitive load, we want to decrease motor response because of motor problems. They might need assistance with being regulated, so offer an extended wait time.

I want to show a video of a small conversation group. You will see two girls with Rett syndrome, as well as a couple of adults. They are trialing a low-tech communication system called a super-core communication book that is available at thinksmartbox.com. I want you to look at how the adult uses communication strategies of waiting, eye contact, talking directly to the girl with Rett syndrome, and acknowledging motor and vocal responses as communicative.

[insert Video 1 conversation group]

The young woman in the green shirt was talking directly to the young girl with Rett syndrome in the red sweater. She was acknowledging head movements, eye gaze as a volitional action, and was inferring communicative intent. The mother who was feeding the other girl was also using eye gaze as a way to acknowledge her daughter's wanting for more. This would be considered a low-tech AAC system. They were trialing core words that are used in everyday life. You could see how she was using the technique of partner-assisted scanning and went through the choices. This way, the little girl knew what they were and went back to see which one she wanted. That was a great example of partner-assisted scanning and modalities for communication.

Assessment

Assessment should be a team process, and you want to have all communication partners in the individual with Rett syndrome's life involved. We want to assess in naturalistic settings, which can help with regulation and anxiety. Just like with anyone you would assess for augmentative communication, you want to assess for opportunities. What are the opportunities in their environment? Who are their partners? Who do they interact with? Regarding barriers to communication, who can help them? A key point to make is that standardized assessments may not accurately reflect an individual's underlying ability. Standardized assessments can be adapted and if you have, for example, a plate with pictures on it, you can reproduce them to make them larger or move them further apart. Make sure to note in your assessment report if someone can indicate through eye gaze.

Dynamic Assessment

There is a way to adapt standardized assessments for people with severe disabilities, but they may not accurately reflect their underlying abilities. Therefore, dynamic assessment is a principle that can be used with individuals with complex communication needs, as well as Rett syndrome. It is a process that has three phases. There is a testing process that provides the opportunity for the individual to show what they can do. You can ask them a question and wait for their response. Remember that they are going to need extended time.

Instead of only noting if the individual cannot do something, proceed to the second phase and provide teaching strategies to help the person make an appropriate response. This may be using modeling, partner-assisted scanning, pictures, or a switch. You can trial eye gaze and see if the individual is able to produce a response using any of the strategies. Phase three is a retest, where you provide another opportunity. Ask the question again because they now have those strategies at their disposal. You can see if they are able to produce the response with that support, and then that becomes part of your assessment report. This is a good tool to use whenever you are assessing someone with complex communication needs, and can be a useful model for assessment in Rett syndrome.

AAC Assessment

Due to the intense eye pointing we see with this population, eye gaze is usually the best access method. However, eye gaze can be fatiguing and should initially be trialed in short periods and increased overtime. A frequent barrier to eye gaze is calibration. However, there are ways to move to trialing an eye gaze system without calibration being established. If you cannot calibrate, that does not mean someone cannot use the eye gaze system.

You want to think of providing a range of symbol systems and depending on where you live, there may be a range of these that you have access to. You may want to begin with a small amount of core vocabulary and then expand. There is another school of thought that would say you are limiting their ability to communicate initially by doing that. Instead, another strategy would start them off with a lot of vocabulary and show them how to use it. Choosing between the two strategies is going to vary based on what you see the individual do, as well as how the family is able to model and use it.

Trial periods are essential. Think about the motor-planning and regulation issues we have talked about. You have to expect inconsistency. This is not a population that you can acknowledge a skill only if it has been done 80 or 90 percent of the time. That is an unfair expectation because of the other issues that are going on with them. That is why it is important to have as long of a trial period with a device as possible so the person has maximum opportunity.

Intervention

When we move towards intervention, our goal should include the development of nonverbal, low-tech and high-tech communication strategies across multiple modalities. Remember that if you have an ambulatory person, they may not be able to use an eye gaze device all the time. This is because depending on how they move, they may not be able to trigger the cameras. When they are ambulating, they need to have another way to communicate. Since these individuals have complex communication needs, and we want to acknowledge all communicative behavior, we need to remember that they are going to be communicating using multiple modalities.

Ways of Communicating

When you are beginning to learn about a person with Rett syndrome, take a look at how they use their body and facial expressions. Do they make any gestures? Are they vocalizing? Can we assign meaning to those vocalizations? Are they able to do some spoken words? Even if their words are repetitive or echolalic, acknowledge them as meaningful. If they look at something or someone, then acknowledge that that eye gaze is meaningful. Think about using a combination of symbols, pictures or text. There is a lot of interest in providing this population with access to literacy, as there should be, and we want to think about that as a possibility.

This second video is of an individual who uses vocalizations to communicate, as well as nonverbal communication. You will see the need for wait time with this individual.

[insert Video 2 of acknowledge nonverbal communication]

The young lady in this video is my daughter, who is why I became interested in Rett syndrome. She was diagnosed when she was 11 years old and is now 30. She is ambulatory, so she does not use an eye gaze device. You can see that she has some preserved hand function. Her hand function has gotten better as she has gotten older. You can see that she uses a lot of body movements. She also uses some eye gaze and vocalizations that we assume are intentional.

AAC May be Aided or Unaided

As you just saw Lisa do with her iPad, she can use direct selection. She does have an isolated finger that she uses to point, but some individuals can activate a switch. Partner-assisted scanning is also widely-used with AAC. One technique for Rett syndrome is reading the available options to the individual, and then they indicate their choice. This is especially important when they are not able to use their eyes to choose the objects or symbols they want. It could be because there are a lot of options on a page and you cannot read which one they are looking at, or it may be because it is too early in the process. We can use modeling or aided-language stimulation to show them how to use a device. We get a lot of questions about individuals who either are not using devices, even as adults, or individuals who are using simple systems who want to move towards complex systems. Aided-language stimulation can work, which is when the communication partner acts as the AAC user. They point to the symbols while talking, adding a verbal message. Also, indicating the symbols can show the individual how to use the system to communicate.

Developing Communication

When beginning to develop communication it is important to establish a yes-no system. That means the individual you work with may not be able to give you a conventional “yes” such as nodding their head or vocalizing, but they might be able to look away, close their eyes, or look at a green check. Some people can do well by learning to use a yes/no strip. That can be something that you start with initially: ask them about something you know they like and see how they respond. You could take that response as their best “yes,” especially as you are starting communication.

You also may have heard of a communication passport, which is a document for AAC users that gives the opportunity to talk about their interests and how they communicate. If an individual has a best “yes,” that is unique to them, you want to make sure you have that information available to their communication partner.

Vocabulary

You want to consider establishing a core vocabulary. These are the words that are used in daily situations, and sometimes devices will call them “quickfires”. Fringe vocabulary includes words that are more specific to a certain activity. In this case you have the ability to design activity boards. An activity board is made for a specific activity, whereas a context-based board includes the words that are just for one situation, such as "going to school".

You can customize the vocabulary based on what the individual’s daily activities are. The point is to then provide that vocabulary in those particular situations using aided-language modeling. This shows them how to use the device and helps them in their communication with partner-assisted scanning.

Access

In terms of access, eye gaze works for most, but it can be fatiguing. You may want to think about an alternative system if the person is ambulating. We also cannot assume that everybody has access to these devices. Also, if an individual has preserved hand skills, we want to maximize those. There is potential for them to get better at hand use and individuals can use more than one access method.

Video 3

My final video is of a mother and her daughter. The daughter is in her mid-20s and started using an eye gaze device when she was 19 or 20 years old, so it is fairly new for her. The communication partner is key to the young woman’s success because her partner believes her actions are intentional. Observe how her mom waits for her and reads her behaviors.

[insert Video 3 for communication partner is key to success]

That pair was a part of a study that we did several years ago, where we worked on coaching the communication partner to wait and acknowledge any behavior that they saw as intentional. That was the key to advancing the young woman in using her electronic device. It also speaks to the idea that it is never too late to begin a complex communication system.

Literacy

Most individuals with Rett syndrome should be exposed to activities to develop:

- Phonemic awareness

- Awareness of print

- A sight word vocabulary

- Writing skills

Like any other learner, we want to provide access to literacy because you never know how far they are going to advance. Augmentative communication and symbol systems have print paired with it in order to provide multimodal stimulation. There is a lot of information on literacy systems and reading programs to develop sight word vocabulary, phonemic awareness, and writing skills.

Summary

I want to end by saying it is never too early to begin communication with this population, but it is also never too late. We used to think that the mortality of this population was higher than their same-age peers, but with improved healthcare and management of some physical symptoms they are living longer. Therefore, everyone deserves access to communication. Thank you for your participation and your interest in Rett syndrome.

Questions and Answers

Does genetic testing in the prenatal period identify Rett syndrome?

If you can get DNA material from the child with Rett syndrome it would indeed identify it. Prenatal testing is not done for a Rett syndrome because it is such a rare disorder. It is also most often not inherited. It is similar to Down syndrome in the sense that is caused by a spontaneous mutation. Nothing from the family history could predict that Rett syndrome would occur.

When does the period of regression begin?

It could occur in the middle of the first year, when they have not gained many skills, or it can start as late as about 30 months.

Is there an age that is too late to work on hand use for switches? I work with a child who uses an eye gaze AAC device, but they would also like access to switches for other activities or when the device is not accessible. She also does not have hand splints.

Going back to the video of my daughter, she got the diagnosis of Rett syndrome when she was 11 because she was not considered a typical person with Rett syndrome. She was diagnosed after the gene was found. Her occupational therapists started her on a hand-strengthening program. I have to credit those individuals on working with her to gain more hand control. As an adult, she can now pick up and hold a cup, put it down, use a fork, a spoon, open a door and so on. She could do none of that when she was younger, and she is not alone. I would say this is something that could be addressed. There is always the potential for learning hand use, but I think you need to consult with an occupational therapist or a physical therapist. You want to identify the dominant hand, especially if they are doing any hand clasping or repetitive hand movements that are considered unintentional. You want to act in a gentle, nonrestrictive way to break that pattern.

When I worked with my student with Rett in the past, we used PODD with partner-assisted scanning, which was similar to what was presented in the video. It was difficult to get responses that seemed on topic or appropriate. With Rett I have heard of a habituation effect, and things need to be constantly made new and exciting. I am not sure that my student was not able to use PODD or PAS, but it was instead boring or too simple. What are your thoughts?

I have heard families say that if their children are being talked down to or the topic is not of interest to them, they will shut down or fall asleep. If that was the case, I would try a few different things. First, I would find their topics of interest and see what excites them. A lot of people think we should only present age-appropriate activities, but I think we should find interests that are specific to that individual regardless of their age. It could also be that the vocabulary might need to be simpler. Some do find that the range of choices on a page might be too big, and that could be a turn-off as well.

With your information about eye gaze, is there a limit on the amount of time a child should be in front of an eye gaze device to communicate?

I think that is going to vary. You do want to give them the opportunity to look at something that is further away. Think about what happens to us when we are looking at our computer screen for a long time. We get eye fatigue. We want to take the same principles that apply to everyone else, and giving 20 to 30-minute breaks sounds reasonable. I know that adults who sit at computers are told to get up at least once every hour. What you want to do is try and work up to the 20 to 30-minute block. You would never want to start somebody out in an intense period. You might want to start for a couple of minutes, then direct their attention to something else and then come back later.

Is communicative intent an important factor for differential diagnosis between ASD and Rett syndrome?

Some children with autism have motor-planning problems, but do not have non-functional hand movements. The problem with assessing communication intent in Rett syndrome is that it is often hard to see because of the physical issues. This could include regulation issues, fatigue issues, and delayed responses. I think it can be easier to identify something that a child with autism is interested in. Sometimes it is going to be harder to see that in a child with Rett syndrome. That is why people used to think those with Rett syndrome were incapable of communicative intent. Children with autism usually have intent, but are not interested in sharing their ideas about it. With Rett syndrome, you do see the intense eye gaze, and that is what I would look for.

Would physical movements such as swinging help with regulation in responses during speech therapy?

It might help with stabilizing the individual and keeping them in homeostasis. For other individuals, it could likely throw them into the overstimulated yellow and red zone, where they might have trouble coming back. In that case it is important to ask our occupational therapist colleagues for suggestions on techniques that can help bring them into regulation.

Are standardized assessments considered a valid measure of language and cognition in individuals with Rett syndrome?

The answer is usually not, because it will likely underestimate their potential. Similar to individuals who have severe cognitive disabilities, those with Rett syndrome are not good candidates for formal assessment of cognition. This is because they can do daily activities that indicate that they have a higher level of cognition. They would then be assessed using a standardized test because you cannot accept qualitative responses in a standardized test. You have to stick to the instructions. I am not suggesting that all individuals with Rett syndrome have severe cognitive impairment. Severe motor impairment, which impacts the ability to engage in a certain environment, is coupled with the physical problems. The severe communicative problem an individual may have can mask cognitive potential. If you could stay away from standardized tests, use criterion reference tests because they describe behaviors and can be helpful in developing an intervention plan. If those tests can be accepted by your institution, that is what I would recommend.

References

Amoako, A. N., & Hare, D. J. (2019). Non‐medical interventions for individuals with Rett syndrome: A systematic review. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities.

Neul, J. L., Kaufmann, W. E., Glaze, D. G., Christodoulou, J., Clarke, A. J., Bahi‐Buisson, N., ... & Renieri, A. (2010). Rett syndrome: revised diagnostic criteria and nomenclature. Annals of neurology, 68(6), 944-950.

Simacek, J., Reichle, J., & McComas, J. (2016). Communication intervention to teach requesting through aided AAC for two learners with Rett syndrome. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 28, 59-81. doi:10.1007/s10882-015-9423-7

Stasolla, F., Perilli, V., Di Leone, A., Damiani, R., Albano, V., Stella, A., & Damato, C. (2015). Technological aids to support choice strategies by three girls with Rett syndrome. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 36, 36-44. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2014.09.017

Townend, G.S., Bartolotta, T.E., Urbanowicz, A., Wandin, H. & Curfs, L.M.G. (2020). Rett syndrome communication guidelines: A handbook for therapists, educators and families. Rett Expertise Centre Netherlands-GKC, Maastricht, NL, and Rettsyndrome.org, Cincinatti, OH.

Townend, G. S., Marschik, P. B., Smeets, E., van de Berg, R., van den Berg, M., & Curfs, L. M. G. (2016). Eye gaze technology as a form of augmentative and alternative communication for individuals with Rett syndrome: Experiences of families in the Netherlands. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 28, 101-112. doi:10.1007/s10882-015-9455-z.

Townend, G. S., Smeets, E., van Waardenburg, D., van der Stel, R., van den Berg, M., van Kranen, H. J., & Curfs, L. M. G. (2015). Rett syndrome and the role of national parent associations within a European context. Rare Diseases and Orphan Drugs, 2, 17-26.

Urbanowicz, A., Downs, J., Girdler, S., Ciccone, N., & Leonard, H. (2016). An exploration of the use of eye gaze and gestures in females with Rett syndrome. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research, 59, 1373-1383. doi:10.1044/2015_jslhr-l-14-0185

Urbanowicz, A., Leonard, H., Girdler, S., Ciccone, N., & Downs, J. (2016). Parental perspectives on the communication abilities of their daughters with Rett syndrome. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 19, 17-25. doi:10.3109/17518423.2013.879940

Citation

Bartolotta, T. (2020). Back to Basics: Guidelines for Management of Communication in Rett Syndrome. SpeechPathology.com, Article 20378. Retrieved from www.speechpathology.com