Editor’s Note: The text is a transcript of the course, Back to Basics: Goal Writing for School-based SLPs, presented by Marva Mount, MA, CCC-SLP.

Learning Objectives

After this course, readers will be able to:

- Explain what SMART goals is and why they are important.

- Describe the process for writing measurable and educationally pertinent goals.

- List 2-3 examples of SMART goals.

Introduction

In this course, I am going to discuss goal writing. You probably won’t hear anything that you haven’t already heard. My hope is that it will help us regroup and do what’s best for our students and their families by writing appropriate goals and objectives for them.

IDEA Requirements

First, I want to quickly review the IDEA requirements for our Present Levels of Academic Achievement and Functional Performance. There are a few different acronyms for that: PLAP, PLAAP, PLAAFP. Basically, it's the part of the IEP where we review the present levels for our students. In order to get into goal-writing, I want to make sure everybody understands how we get to the goal-writing piece and what information needs to be included in the IEP.

Factors to consider when developing the present levels (PLAAFP) include the student’s academic functioning, their critical need, current measurable and observable data, data sources, any conditions that surround their measurable performance (e.g., modifications or accommodations), and enrolled grade-level content standards.

As school-based SLPs, we need to make sure that we are aligning goals with the academic standards. Many states use the Common Core State Standards and some states have written their own. Whatever the standards are for your state, make sure you understand what is contained within those standards in the areas that apply to speech and language.

Also, the IDEA requirement for PPCD (i.e., Early Childhood Education and Pre-K) focuses on how the student's disability affects their participation in appropriate activities. Because those children are around ages 3-5, they don't have academic standards. However, they do have standards for appropriate activities for their age level. In grades K-12, we want to know how the student's disability affects their involvement and progress in the general education curriculum.

34 Code of Federal Regulation §300.320 - Definition of Individual Education Program

Regarding the codes in the Federal Regulation's definition of Individual Education Program, one of the statements speaks specifically to PLAAFP as well as the child's involvement in general education. I wanted to bring that to your attention in case you want to take a look at that.

Present Levels of Academic Achievement and Functional Performance

Present Levels of Academic and Functional Performance (PLAAFP) is important because it provides the student's competencies. It identifies areas of critical need. It identifies what facilitates learning for that student, as well as what inhibits learning. It determines appropriate measure of growth, and provides the information needed to design specialized instruction for the students. This specialized instruction is the goal-writing section of the IEP that we will discuss in this course.

If you don't write a good PLAAFP, then the student will not have strong measurable goals. The PLAAFP is important because it covers specific types of academic information and skills the child has mastered. It also covers other areas that are not academic, such as social communication and activities of daily living for students who may be in more of a self-contained special education classroom.

For children who have disabilities in addition to speech, we also need to look at the curriculum being used with students in those classes so that our goals align and mirror what is happening for that child academically.

In the PLAAFP statement, we are describing the what, how, and how much the student is learning in specific areas. The statement also includes adequate information about the student in order to design the specialized instruction, which are the goals we're going to discuss.

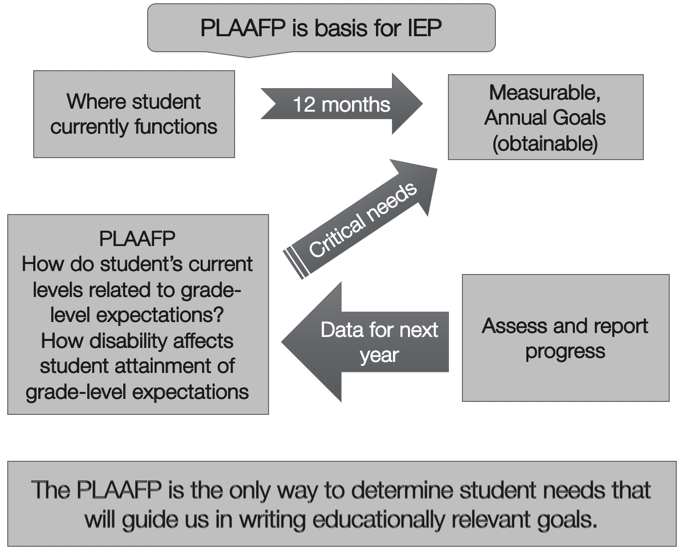

Figure 1 provides some perspective. The present levels look at where the student is currently functioning. Then we're going to look 12 months out for measurable, annual goals to make sure they're obtainable. We never want to write a goal that is continually carried over for a student from year to year. If we are doing that, then there's something wrong with our connection between what the present level of the child is and what their goals and objectives might be. Always think in terms of what the student can accomplish in 12 months. Sometimes that's easy to determine, sometimes it’s not. Sometimes, with some of our lower-functioning students, we have to take an educated, professional guess in terms of how quickly they'll progress.

Figure 1. PLAAFP is basis for IEP.

The point of Figure 1 is to serve as a reminder that when looking at the critical needs of a student, we are aiming for progression. However, we don’t want to “over-aim” in terms of what we expect the student to do within a year. Sometimes we write goals that are a bit complicated and we have high expectations for a lot of progress. In those instances, when we meet with the IEP committee, we can always adjust those goals. We can make them more difficult, or we can make them less difficult, depending on how the student performed.

The present level is the only way to determine the student’s needs that will guide us in writing our educationally relevant goals. I like to have this chart in front of me when I start writing a student’s goals and objectives so I remember all of the factors that need to be considered in goal writing.

The PLAAFP must be the basis for writing educationally-relevant goals for the child's educational year because that leads us to next steps in the process of goal and objective writing. If we fail in writing the present levels, then the goals and objectives may not be appropriate for the student. The goals may be too high-level or too low-level. We may have expected a lot more than what we're actually going to see in that annual year. Present levels shows the child's academic strengths, academic challenges, what is facilitating the child's learning, what inhibits the child's learning, what their current levels of functioning are, as well as data that is specific, factual, and operational.

It is within the present levels, that we provide data from some evaluations. If the child is new on our caseload, we will be giving information and factual data on how the child performed on the educational assessment or speech and language assessment, so that we know at what level the child is currently functioning. If the child has been on our caseload for a while then present levels will contain all of the data that has been collected over the year during each therapy session. We are using that data to complete the functional levels of performance.

The PLAAFP Process

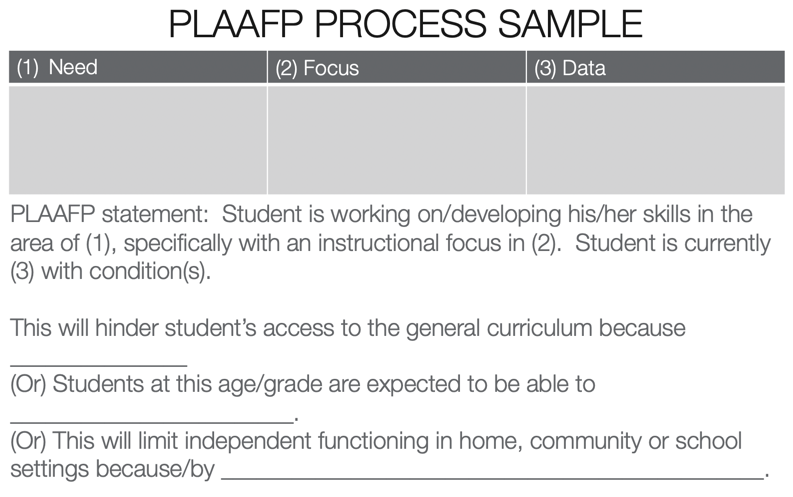

Figure 2 is a PLAAFP process sample. I remember this being tricky when I first started doing them because I wasn't sure how to word things, and I wasn't sure what components needed to be addressed.

Figure 2. PLAAFP process sample.

Examples of present level statements include:

“Student is working on developing his or her skills in the area of ______________ (this could be fluency, articulation, language, etc.) with an instructional focus in _____________________. Student is currently ______________________(evaluation data, therapy data) with condition.

Those are the three primary areas for the present levels that need to be included in order to write goals and objectives for the student.

If we think of the PLAAFP as the story of a student, then we are writing an educational story for them in this section. That can help with organizing and providing appropriate information so that when the parent or other team members read those present levels, they have a complete picture of the student and everyone is on the same page.

As an aside, some of the online special education paperwork systems don’t allow for much information in the PLAAFP section. This is unfortunate because it is the portion of the IEP that drives the entire process. If you are working with online paperwork systems that don’t allow for much information (i.e., character limits) then just do your best. Sometimes I will add an addendum. If I know the parents are very concerned, I may put some additional information in another section in order to give a complete picture of what the student’s present levels are. That’s not required, obviously, because the data can speak for itself, just be sure to be thorough in the PLAAFP section of the IEP. It can be very difficult to explain why you chose certain goals and objectives for a student if the information isn’t available to all team members.

What Happens when SLPs DO Align Their Goals with the Educational Standards?

When we align goals with the educational standards we are linking them to the general education curriculum, which is very important. We have statewide testing in my area and students have to have passing scores on that statewide testing in order to move from grade to grade and to graduate from high school. Therefore, it’s very important that I am aware of what my students need to know and what they have to do on these statewide tests in order to pass and move on to other grades.

Aligning goals with the education standards also helps because we need to know what's going on in classrooms in terms of the materials we choose and what we like to work on with students. It’s hard to figure that out if we don't look at those standards and understand them.

We also support students who are most at risk in public schools. Children in special education, in general, are at risk not only for falling behind educationally, but drop-out rates are much higher with students that have special needs as well. So, the IEP team must collaborate and support students to ensure that goals are functional academically.

We can also explicitly target academic language skills that will greatly improve academic relevance. SLPs, as you know, are not always recognized for the talents, skills, and professionalism that we bring to the academic setting. Explicitly targeting academic language skills is a great way for us to show administrators and special education teams what we know and how we can help explicitly. Not only does this promote us in our school-based programs but also in our profession in general.

Our goals will elevate the academic language skills of students with language disorders because we know how to break the goal apart. We know how to break it down and put it back together in terms of what is developmentally appropriate and what stages and steps students need to make it to the next level. We bring so much expertise to this particular part of the goal-writing process for our students and we need to take advantage of that.

We also ensure that our goals are rigorous and farsighted with respect to students' academic futures. Not all of our students will want to go to college, but some of them might. So, we want to start as early as possible to prepare those children for careers in college education, especially if they have language deficits. We need to begin doing that as early as three years old. We need to make sure they have the vocabulary, language, and grammatical components. We need to make sure that they can function in public schools and beyond that when they transition out into the world.

If we don't align goals with educational standards, we're diluting those language-related achievements that our students have and we deny them benefits that they could experience through a collective impact.

Collaboration is important, especially for children who are seen by other special educators. Team members need to be on the same page in terms of how to write student goals and objectives. We must collaborate. We need to infuse educational standards into our IEP language. Obviously, we don't all speak the same language in the educational setting. There are terms and conditions that are speech and language-related. Teachers may have those same terms and conditions that are educationally related, but call them something different. We need to speak the same language and know that semantics means vocabulary, syntax means grammar. Then, we need to be respectful of the fact that everyone on the team may not know the correlation between those words.

We also need to make the curriculum accessible to our students by matching treatment targets with their educational needs. What better way to do that than by understanding the language of our educational standards and incorporating that into what we do as speech-language pathologists.

Why Is It Important?

We've already talked about a lot of these, but students with speech and language deficits require additional teaching and practice in order to perform well in the classroom. We all know that. If they didn't require additional teaching and practice, they probably wouldn't be on our caseload.

We need to take advantage of that extra time to focus on the types of educational needs students will experience in the general education classroom.

Our goals and objectives need to be written in a way that allows students more practice and more teaching in curriculum areas that are more difficult for them. Standards-based instruction provides a framework to teach those concepts across standards, it promotes sequential learning with a longitudinal plan, and builds competence over time.

I have many students on my caseload who are language impaired. These students are easily defeated because they see me in a pull-out situation and do really well with their goals. They get it. But then they go back to class and the same concept is taught in a different way by the classroom teacher with different vocabulary and different materials. We all know how difficult it is for our students to generalize what they are learning with us into their classroom. We must ensure that our students understand that what they are working on with us is also what the teacher is working on in the classroom. That’s not easy for them to do unless we use the same vocabulary and materials that they'll come into contact with every day.

Areas of Standards

Our standards cover language, listen, speaking, and writing. Most standards, whether it is the Common Core or some other standard-based instrument that your state utilizes, always have a section of language and how that relates to listening, speaking, and writing in an educational setting. All of those areas are within our clinical expertise. We know how to address them with our students.

SMART Goals

Criteria

What is a SMART goal and why are they important for our students? The acronym SMART stands for Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound. Specific refers to students' present levels of academic achievement and functional performance (PLAAFP), as previously discussed. Measurable means that progress is objectively determined at frequent data points. We are all aware of how important it is to make sure our goals are measurable and that we can collect good data on those goals. Achievable refers to goals being realistic and related to students' most critical needs. Remember, in that calendar year of that annual IEP, we need to make sure that we are making the goals achievable during that period of time before the next review. We want goals to be relevant, so we need results-oriented goals and objectives with a standard outcome in mind, which is why it is necessary to understand what the standards require of our students. Finally, goals need to be time-bound. There needs to be a clearly defined beginning and end date. Again, if you have an IEP on September 10th of 2019, you will have an ending period one year following that when you reconvene as an IEP committee and determine what the next steps are for the student.

Specific - Goals need to be specific because we want to know exactly what that student has to do. In order to do that, they need to be well-defined. We have to have a clear outcome, and we need to provide adequate details in terms of what the expectation is for the student.

Measurable - There needs to be some type of measurement. Is it a percentage or so many times out of total number of trials? There are many different ways to measure a goal or objective. There is no set way and is largely dependent on how the goal is written.

Achievable – An achievable goal would contain, as an example, “within 36 weeks” or “within 12 months.” Specify the timeline that the student has to achieve that goal and objective. Oftentimes, our long-term goal is for a 12-month period. Then our short-term goals and objectives, or our benchmarks, may have varying degrees of length. For example, we may start out with a short-term goal that we think they can achieve in 12 weeks, and one that they may be able to achieve in 20 weeks, etc., until we reach that 12-month period when the long-term goal ends.

Relevant – The goal must be educationally relevant in the school setting.

Time-bound – Goals are time-bound based on the terms of the IEP.

Why Smart Goals?

SMART goals state desired future achievement for the student. We are always looking ahead. What does this student need in order to be successful in the second grade, the third grade, or the 12th grade? SMART goals assist in focusing on what a student's primary needs are through the present levels. They help to define exactly what the student’s future achievement looks like and how we're going to measure it. If we follow the SMART process, then we should be writing some really great goals and objectives for our students.

Components of Measurable Goals

There are also components within these SMART goals. Components are aspects of that goal and objective that help us cover all of our bases. The first one is condition, sometime also referred to as quality. Condition specifies under what conditions the behavior will occur. For example, in what setting or using what materials and/or with what supports. Materials does not mean naming the specific materials (e.g., “using Super Duper cards” or “using LinguiSystems cards”) we plan to use. Rather, it’s a type of roadmap for how we plan to get the student to achieve the goal. Remember, it’s not a great idea to name the specific materials because if the student moves to another location and that therapist does not have the same materials, that becomes a problem for that goal.

The next component is behavior, or the learning performance, of the student. It identifies the observable and measurable performance expected. It answers the question, “What will you see the child perform or do?” We want to specifically state what we want that student to do in order to master that goal and objective.

The third component is criteria which identifies how much of the behavior the child is expected to perform for the goal to be met. It answers the question, “To what level does the student need to perform this behavior?”

Finally, timeframe is the amount of time it will take to attain the goal. This always answers the question, “How long do I think it will take this student to perform the behavior to this specific level?”

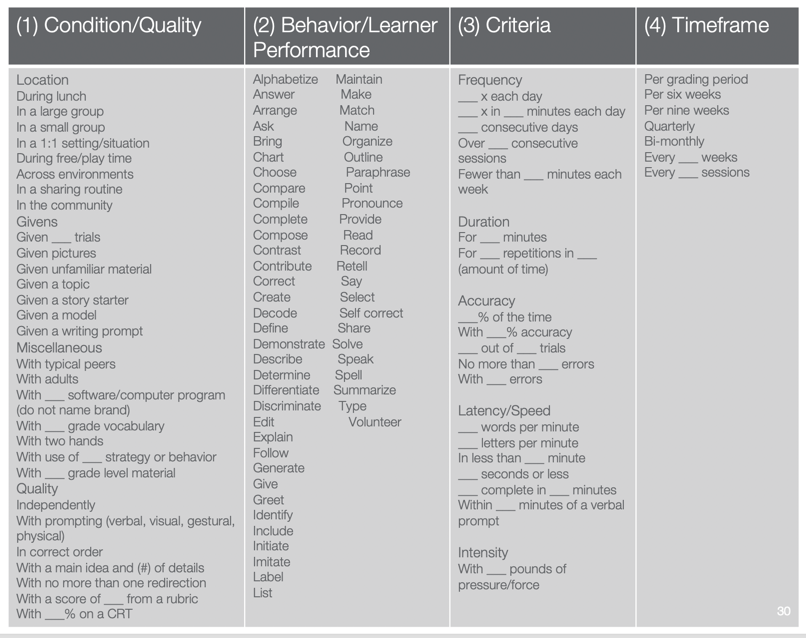

Below is a chart that might be helpful for looking at condition/quality, learner performance, criteria, and timeframe (Figure 3). Sometimes a visual can really help jumpstart our thinking when we sit down to write goals and objectives.

Figure 3.

Condition/quality. The first column is Condition/Quality and it is broken down into different factors like “Location” or “Givens”. A location example would be, “"During lunch group, a student will…," or, "In a large group, a student will…," or, "In a one-on-one setting or situation, this student will…" This is a list of suggestions for ways to meet the condition/quality component of the goal.

“Givens” are “Given X number of trials…” or “When given pictures…” or “When given unfamiliar material, the student will…” There are numerous examples to add in terms of condition or quality.

There are some miscellaneous terms and phrases also listed. For students who are working on social skills, it can be challenging to come up with how we want them to react in social situations and with whom. We might talk about “with typical peers” or “with adults”. We might want the goal to include, “…with certain grade-level vocabulary”, etc.

Quality is how the goal will be met such as “independently”, “with prompting”, “in correct order”, “with a main idea and X number of details”, “with no more than one direction.” These are examples of how to meet that condition or quality component.

Behavior/learned performance. The chart lists some great suggestions for writing a goal that is measurable because we are indicating exactly what we want them to do. We don't use words like learn or will know because that can’t be measured. We can't really measure learn. So, this column lists words that will make that goal and objective measurable in terms of behavior: alphabetize, answer, self-correct, summarize, give, identify, include. Those are all words that are definitely measurable and we can take data on without any problem. This is, obviously, a very small percentage of some of those behavior terms that are measurable.

Criteria. This refers to frequency, duration, accuracy, latency/speed, or maybe intensity depending on the type of a goal being written. It may be X number of times per day, X number of times in X number of minutes. It could be over consecutive sessions. With stuttering, we may look at duration and accuracy. Figuring out how to word a goal can be challenging. Having a list of examples like this can help.

Timeframe. I receive many questions about how the timeframe should be written on the scheduled of services section of the IEP. My advice is to write it the way the district wants you to. Each district has its own view on how the timeframe should be written. Some school districts want it by grading period. Some want it by grading quarterly, every so many weeks, or every so many sessions. There is no definitive answer for the best way to write that so it is best to follow the districts instructions. Additionally, some IEP electronic paperwork is already set up a certain way and doesn’t allow the delivery model or service model to be changed.

When writing the timeframe, remember that there are many interruptions to our therapy sessions – field trips, testing, benchmark testing, statewide testing, etc. Therefore, it is better to write the goal for over a period of time rather than “so many times per week”. It allows for more flexibility to meet those established minutes per grading period as listed on the schedule of services. Writing the timeframe as “weekly” restricts the ability to make up those minutes if the child is involved in another activity or event.

Model for Goal Writing

Along with the components just discussed, there are other parts to the goal that must be included. SMART goals will always include:

- WHO - The student

- WHAT - What will the student need to do? Is it measurable and observable?

- WHEN (timeframe) - How long does the student need to work on the goal?

- WHERE (conditions) - Setting, situation and materials

- HOW (criterion) - To what level or degree must the student perform.

- ASSESSMENT - What level of assessment will be used to measure progress and attainment of that particular goal?

This model tends to work better with the special education paperwork compared to the SMART or Components model. However, all three are very similar and one of them should work for you and your district requirements.

Goal Components

Goal components can be ordered this way:

- By when will the person do it?

- Who will do it?

- What will they do?

- How well will they do it?

- Under what conditions?

For example, “By the end of X, John will be able to produce the “s” sound in phrases with 80% accuracy without models provided.” That goal covers all of the goal components for what needs to happen in order for it to move the student forward.

There is also a seven-step process for creating standards-based IEPs created by Project Forum at the National Association of State Directors of Special Education Conference (NASDSE, 2007). The process was presented to classroom teachers and special education classroom teachers, but I found it very useful for writing speech and language goals. I have modified the steps slightly but I do follow the basic model and want to give the NASDSE credit.

Step 1: First Write/Review the PLAAFP

The first step is to review the assessment date and determine the present levels (PLAAFP). For example:

Sally is a 4-year-old student with autism. She displays occasional verbal and physical outbursts to demonstrate frustration over shared materials or when she cannot move about the classroom as she chooses. She follows a visual schedule for her daily routine and can independently manipulate the schedule pieces as she progresses through the day. She has learned to look at the next picture on her schedule and will verbally state what comes next, i.e. “computer”, “PE”, “lunch”.

Sally uses one- and two-word phrases to express wants and needs, primarily with adults. According to her mother, she “plays” with her older sister, but social interaction with peers is limited to parallel play in various areas of the classroom. When observed in various school environments, Sally did not independently initiate interactions with peers. When observed over the course of multiple days, Sally initiated peer interactions a total of 2 times on the playground when an adult provided a verbal instruction and verbal, gestural or visual prompts (picture) to initiate the interaction.

The statement tells WHO (Sally) and WHAT she displays (verbal and physical outburst). The statement indicates that she uses one- and two-word phrases, and specifically HOW. It includes additional information in order to give a complete picture of a functional analysis for Sally.

Again, that is a sample of what a PLAAFP statement might look like for a student.

Step 2: Prioritize Needs

Step two is prioritizing the student’s deficit areas. With the example of Sally, she has multiple deficit areas and for a four-year-old, some of those deficits are pretty significant. Her speech and language skills are very poor.

We want to take the information known about Sally and prioritize it so that she doesn’t have an IEP with 85 goals and objectives. Sally will never function and make progress if too many goals are written. We want to prioritize her needs by identifying those that are most likely to hinder her access or progress in her special education preschool classroom.

Sally’s areas of concern are the verbal and physical outbursts, which is not surprising because she can’t communicate and that behavior is a form of communication. Teachers may not understand that so we can discuss that with them. Additionally, Sally has very limited social interaction. She has only been seen in parallel play with students in her class. She does not initiate interactions with peers independently, and she has limited verbalizations.

From a speech and language perspective, her inability to interact independently and her limited verbalizations are priority needs for Sally if she is going to access all areas of her current educational setting.

Another question to consider is what is most likely to hinder the student’s success? For Sally, it is her limited verbalizations and interactions with peers. Those two areas should be included in her IEP.

Step 3: Review Academic Standards

In the case of Sally, there may not be academic standards. Rather, there might communication standards and/or socialization standards. We want to review those since we know they are deficit areas for Sally. For prekindergarten, the guideline is, “The child shows competence in initiating social interactions.” We can take this standard and decide where we need to start developmentally with Sally to get her to the point where she can show competence in initiating social interactions.

Step 4: Correlate Deficit Areas

Step four is to correlate the deficit to a standard. We want to match that priority deficit skill to a corresponding educational or functional performance area. The selected areas should be those that determine the greatest potential to accelerate the student's achievement. The aim is to close the gap.

For example, Sally’s skills include using a picture schedule independently and anticipating what comes next in her schedule. She can use one- and two-word phrases to express wants and needs consistently with adults. She may not be doing that with her peers, but she's able to do it with adults, probably when prompted. Additionally, she exhibits social initiation in controlled environments with multiple prompts using a two-word phrase. Meaning, if someone assists her to make that social initiation, she can do it. But it requires a lot of prompting. Finally, Sally demonstrates parallel play alongside her peers. It’s not that she doesn’t want to be around the peers, she just can’t turn her parallel play into interaction yet.

The skills that Sally needs include showing competence in initiating social interaction, actively seeking out play partners, and appropriately inviting them to play. These are areas of need for Sally based on the standards for functional performance for her age level.

Step 5: Develop Annual Goal

The next step is to develop the annual goals and objectives. After the deficit skill areas have been identified with corresponding educational needs for the student, annual goals are developed.

Using the SMART acronym, what goals can be written for Sally?

By Sally's next annual IEP (4), given a verbal instruction and no more than one verbal prompt (1), Sally will approach a peer during a structured playtime and invite him or her to play by making a verbal request, such as, 'Play with me?’ (2) as evidenced by making the request for five consecutive school days during one grading period (3).

Because Sally can use one- and two-word phrases already, we want to bump her up to three words. Sally is going to have to initiate those social interactions five consecutive school days during one grading period. That's how we're going to measure her progress.

Step 6: Developing Short-Term Objectives

Step six is to develop short-term goals and objectives. Short-term objectives (STOs), also called benchmarks, are no longer required by federal law. When IDEA 2004 was rewritten and reauthorized, it removed the need for short-term objectives to be listed on a child's IEP unless that student was taking some type of alternative assessment aligned with alternative achievement standards. Those are the students who need modifications to be made to the grade-level content. In that instance, it is still required by federal law to write short-term goals and objectives. For more information on that IDEA federal requirement, go to 34 CFR Section 300.320.

For students who have SLI with no other disability categories, their grade-level content is not typically modified. Only accommodations are provided to help them reach their goals. Likewise, students with only speech impairment will not have modified content and we are no longer required to write short-term goals or objectives unless the district or state requires it. It IS ok for districts and states to continue to require them.

In many instances, short-term objectives are the building blocks for the student to reach the annual goal. Each STO or benchmark can be individually measured with data collection. Having STOs can make it a bit easier.

Example of possible STOs for Sally include:

By the end of Sally’s fourth reporting period, given a verbal instruction paired with a verbal, gestural and visual prompt, Sally will interact with a peer in a short-structured activity by sharing materials for up to five minutes over five consecutive interactions, as evidenced by data collection by the classroom teacher and the speech pathologist.

If the objective is only going to be measured by you, as the SLP, then state that. In my school, goals are written for younger children such that communication goals are worked on by the SLP and the classroom teacher. All of the components of the goal are there: who, why, when, how much, and how it will be evaluated. This is a very important step if Sally is going to master the standards that are required for her pre-K classroom.

Another example:

By the end of Sally’s second reporting period, given a verbal instruction paired with a verbal, gestural and visual prompt, Sally will demonstrate appropriate turn taking skills during an adult-directed play task with a peer over 5 consecutive interactions, as evidenced by grading turn taking using a social skills interaction rubric.

The first STO states, “By the end of Sally’s fourth reporting period” because that goal is going to take more time for her to reach. Her second STO states, “By the end of Sally’s second reporting period…” because it is not expected to take her as long to master that STO compared to the first one.

Essential Elements Cheat Sheet

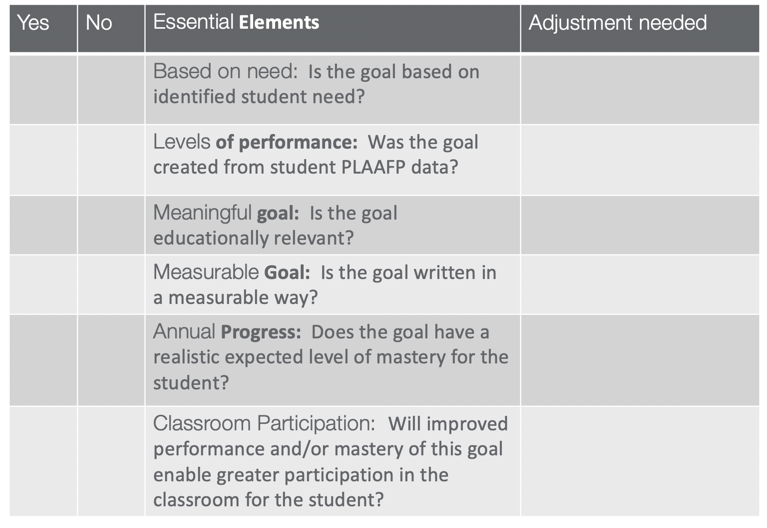

Figure 4 is a cheat sheet that can help break goals apart in a systematic and organized way.

Figure 4. Essential elements cheat sheet.

The essential element is listed in the center of the table with a “Yes” and “No” column to the left of it. If “Yes” is checked then that suggests the goal is based on identified student need. If you read the essential element to yourself and think “No, it’s not really based on need," then check the “No” column and adjust the goal to address what their need is now based on what they can do. Do the same check for levels of performance, meaningful goal, measurable goal, annual progress, and classroom participation. Again, this is a chart to help with goal writing if needed. Figure 4. Essential elements chart.

Goal writing is an area that many SLPs struggle with. As we inherit folders and IEPs with goals written by other SLPs, we want to show some grace to the professionals who came before us before jumping to the conclusion of, “What were they thinking. How is that goal measurable?” Let’s take the opportunity to write goals in the right way and not worry about how the goal was given to us.

Collaboration

The last item to discuss is collaboration. We hear a lot about interprofessional collaboration and ASHA has quite a bit on the topic as well. It's very important to collaborate with our colleagues and demonstrate how effective we can be with students that are having educational challenges. It starts with us - how we present ourselves and how we collaborate with our colleagues. I encourage you to get into classrooms. Be a well-known person in your building and be a source of knowledge and information to others.

When we collaborate, we're increasing the value of what we do so that others can do it too. We're also increasing the value to our students in terms of knowledge and skills that we can help them acquire. If you are a middle and/or high school SLP, it’s extremely important to motivate your students and help them understand why they to come to speech therapy. Instead of the rolling of the eyes or “getting lost” on the way and never show up, it’s important that you share what you know with them and what you can help them do.

References

Below are some references that I refer to on a regular basis. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act of 2004 can be accessed at sites.ed.gov. If you're new to the profession, look through the references and understand what the requirements are for you as a special education provider. Speech is a special education service in the public schools. Be aware of what you need to know as a speech-language pathologist working with students in the public schools.

Blosser, J., Roth, F. P., Paul, D. R., Ehren, B. J., Nelson, N. W. & Sturm, J. M. (2012). Integrating the core. The ASHA Leader.

Capitol Region Education Council. The BluePrint: Building Powerful Special Education Practices (2013). Hartford, CT.

Ehren, B. J., Blosser, J., Roth, F. P., Paul, D. R. & Nelson, N. W. (2012). Core commitment. The ASHA Leader.

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. 2004. Rules and regulations retrieved from www.sites.ed.gov.

Justice, L. (2013). From my perspective: A+ speech-language goals. The ASHA Leader.

Mount, M. (2014). Facilitating cohesive service delivery through collaboration. Perspectives on School-Based Issues. 15, 15-25.

National Association of State Directors of Special Education (2007). Available at www.nasdse.org.

Power-de Fur, L. & Flynn, P. (2012). Unpacking the standards for intervention. Perspectives on School-based Issues, 13, 11-16.

Citation

Mount, M. (2020). Back to Basics: Goal Writing for School-based SLPs. SpeechPathology.com, Article 20343. Retrieved from www.speechpathology.com