From the Desk of Ann Kummer

Understanding the basis of speech sound disorders and choosing appropriate interventions for treatment can be very challenging for pediatric speech-language pathologists. Therefore, I am delighted that Carol Koch, EdD, CCC-SLP has agreed to answer common questions regarding speech sound disorders for this edition of 20Q.

Dr. Koch is a well-known and highly respected expert in speech sound disorders. In fact, she has authored the following book on this topic: Koch, C. (2019). Clinical Management of Speech Sound Disorders: A Case-Based Approach, Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett, Inc.

Dr. Koch’s book is based on her extensive clinical experience and her academic endeavors. She has been a practicing clinician for 30 years with a clinical focus in early intervention and preschool speech disorders. She has a particular interest in children who are highly unintelligible. In addition, Dr. Koch has been in higher education for about 12 years. Her teaching and research interests have included phonetics, phonology, speech sound disorders, childhood apraxia of speech, and phonological development of very young children. Other areas of interest have included pediatric feeding disorders, autism spectrum disorder, family and sibling experiences with autism spectrum disorder, and the impact of trauma on child development.

Dr. Koch is currently Professor in Communication Sciences and Disorders at Samford University in Birmingham, AL, where she also serves as the Graduate Program Director in Speech-Language Pathology. In addition, she has been actively involved in ASHA’s Special Interest Group (SIG) 10 as a member of the Coordinating Committee. Interestingly, Dr. Koch has also traveled as a professional delegate with People to People Ambassador International to New Zealand, Australia, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Israel.

I think you will find that this course will increase your understanding of speech sound disorders, and help you to choose appropriate interventions based on current evidence.

Now...read on, learn and enjoy!

Ann W. Kummer, PhD, CCC-SLP, FASHA

Contributing Editor

Browse the complete collection of 20Q with Ann Kummer CEU articles at www.speechpathology.com/20Q

20Q: Speech Sound Disorders: "Old" and "New" Tools

Learning Outcomes

After this course, readers will be able to:

- compare traditional and nontraditional criteria for selecting treatment targets for children with speech sound disorders.

- explain each of the contrast approaches: minimal, multiple, and maximal oppositions.

- create and implement effective interventions for students using evidence-based practices.

1. What are speech sound disorders?

The term is intended to encompass the two most common subtypes of speech sound disorders: articulation disorders and phonological disorders.

2. What are the key features of an articulation disorder?

An articulation disorder is characterized as speech sound errors that are related to the motor skills needed to produce speech sounds. The term refers to an inability to physically produce speech sounds. A child demonstrating an articulation disorder has difficulty with the motor aspect of speech sound production. The difficulty lies in the phonetic level, or form, of speech sound production. Articulation disorders reflect difficulty in the perception, discrimination, and motor production of speech sounds. The motor production aspect involves the ability to move and position the articulators for accurate speech sound production. Articulation errors are commonly described in terms of sound substitutions, omissions, additions, and/or distortions of the target speech sounds (Koch, 2019)

3. What are the key features of a phonological disorder?

A phonological disorder is characterized by a difficulty in organizing the sound system to create meaningful linguistic contrasts. The impairment lies in the phonemic function of the sound system, or the function of sounds to create different words. A key feature of a phonological disorder is in the loss or neutralization of phonemic contrasts. For example, a child might consistently produce “pour” for “four” but also accurately say “pour” for “pour”. This example exemplifies that the child is not demonstrating the use of the phonemic function of “f” to create a meaningful contrast between the words “pour” and “four” (Koch, 2019).

4. Can a child demonstrate characteristics of both an articulation disorder and a phonological disorder?

Despite the importance and clinical significance of a differential diagnosis of the nature of speech sound disorders, it is possible that a child may demonstrate features of both an articulation disorder as well as a phonological disorder. It is best to not view the two disorders as mutually exclusive (Strand & McCauley, 2008). Children may demonstrate difficulty in the motor production of sounds as well as in the ability to use those sounds contrastively to create meaningful words. Assessment information must help us to identify each child’s unique skills and areas of deficit to identify the most effective approach for intervention.

5. What target selection criteria are commonly utilized?

Target selection factors offer speech-language pathologists (SLPs) the opportunity to link assessment data with intervention planning and implementation. The impact of target selection on the efficacy of speech sound intervention is a challenge faced by SLPs every day. The efficiency with which children acquire accurate speech sound production is influenced by the selection of intervention targets.

The traditional approach for target selection, which emphasizes phonetics, or the surface forms of speech sounds, is based on developmental norms and stimulability for error phonemes. Initial intervention targets were selected from speech sounds that were early developing or considered to be age appropriate targets, sounds that were stimulable, and sounds for which the child demonstrated inconsistent errors. The traditional approach to target selection emphasizes sound learning. The rationale for the traditional approach was that earlier developing sounds that were stimulable were easier to teach and learn, followed a developmental progression for acquisition, and would result in relatively rapid success (Koch, 2019).

6. But what about this “new set” of target selection criteria?

“New” methods of target selection have been examined to determine the factors that facilitate more efficient progress in sound acquisition. The non-traditional or complexity approach for target selection emphasizes the selection of sounds that are non-stimulable, later developing, are characterized by consistent error patterns, and represent the least phonological knowledge. The rationale for the non-traditional approach reflects a shift in treatment focus from sound learning to system reorganization. When the desired treatment outcome is system-wide change, the nontraditional approach is utilized to guide target selection (Gierut, 1992).

7. Can we still use developmental norms for making intervention decisions?

Developmental guidelines for speech sound acquisition continue to be utilized in assessment, diagnosis, and intervention decisions (Bernathal, Bankson, & Flipsen, 2017; McLeod & Baker, 2017; McLeod & Crowe, 2018). Educational settings may also utilize these norms as a basis for eligibility decisions for children who demonstrate speech sound disorders.

8. What are the primary strategies for the articulation or motor-based approaches?

The primary strategies utilized in motor-based approaches include:

Auditory stimulation or imitation: the clinician provides a model of the target sound for the client to imitate. The level of difficulty can be modified by adjusting the time from auditory model to the child’s production (Jakielski, 2011; Strand, Stoeckel, Baas, 2006; Strand & Skinder, 1999). As the amount of time from the presentation of the model to when the child produces or imitates the model increases, the level of task difficulty also increases (Strand, Stoeckel, Baas, 2006). Simultaneous imitation, or choral imitation, is when the clinician and the child produce the target at the same time. Mimed imitation is when the clinician silently mouths the target, providing a visual model of articulatory postures, as the child observes and then the child produces the target aloud (Jakielski, 2011). Immediate imitation is when the child repeats the target immediately following the clinician’s auditory model. Imitation in successive repetition is when the clinician provides a verbal model and the child produces the target several times in succession without receiving an additional model (Jakielski, 2011). Delayed imitation is when the child produces the target several seconds after the clinician provides the model, including additional linguistic information (Strand et al., 2006). For example, the clinician might say, “This is a cat. He has black and white fur. What is this?”

Phonetic placement: When a client is not able to produce the target sound in imitation, the clinician begins providing instruction for the correct position or placement of the articulators for production of the sound. The verbal instructions include descriptions of the positioning of the articulators, the points of contact between the articulators, and the motor movements needed to accurately produce the target sound. For example, the clinician may instruct the child to “make your upper teeth touch your lower lip and blow air to produce the /f/ sound”. Visual or physical/tactile strategies that may be incorporated into the phonetic placement approach include: directly observing the mouth and placement of the articulators (Secord et al., 2007), using a mirror for visual feedback, drawings that depict the position of the articulators (McLeod & Singh, 2009), and the use of tongue blades to manipulate the articulators (Bleile, 2006; Secord et al., 2006) or to direct the airstream.

The procedure for successive approximation involves the shaping of new sounds from sounds or articulatory postures in the clients existing sound inventory. This approach builds from the placement of an existing sound that is similar to the target sound. Analysis of the existing inventory and the potential targets may reveal phonemes that share common production features. The existing sound serves as the starting point. Through successive modification or adjustments in either the position or movement of the articulators or the manner of production, each step results in a closer approximation of the target sound. For example, the phoneme /t/ may be used to facilitate the correct production of /s/ (Secord et al., 2007). The alveolar place of articulation is similar for both sounds. When the client is instructed to release the /t/ with a strong burst of air, while slowly retracting the tongue lightly from the alveolar ridge, the resulting sound can be prolonged and will approximate an /s/ sound. Once a sound close to the target is produced, auditory stimulation, imitation, or phonetic placement strategies can be utilized to refine the production accuracy of the target phoneme.

Contextual facilitation: Another strategy for establishing a sound involves identifying a phonetic context which results in a correct production, even when the sound is typically produced in error in other contexts (Bleile, 2006). Some contexts may facilitate the correct production of a sound. If a context that results in the correct production of a sound can be identified, that context can facilitate correct production of the sound in other contexts. An example of a facilitating context is the phoneme /t/ before the phoneme /s/. The articulatory contact of the tongue tip elevated to contact the alveolar ridge may facilitate correct production of an /s/ sound that may otherwise be produced as an interdental phoneme. In this example, a word pair such as hot-seat would provide a potential facilitating context to establish a correct sound production of /s/. This strategy of using a phonetic context to establish a new sound production builds from an existing skill in the client’s speech production abilities. In this way, the strategy is also considered to be a form of shaping. One phonetic context is being utilized to shape, elicit, and establish production of a target phoneme.

Methaphonological cues and metaphors: Metaphonological cues are verbal cues provided by the clinician that reflect information about either an acoustic or visual feature of the target sound that the child needs to use (Howell & Dean, 1994). For example, a child may say [ti] for the word “see”. The clinician might respond with, “I heard you use a short sound when you said ‘see’. Try saying it again with a long sound like ‘sssss’.

Metaphors can be used as a means for describing a sound or prosodic features of sounds (Fish, 2011). This strategy allows a rich context for talking about and defining sounds targeted in therapy. For example, [ʃ] may be described as the “quiet sound” and may also be accompanied by a single finger gesture to the mouth when the sound is modeled. Using metaphors or metaphonological cues provides a clinician with a way to prompt the client without providing a model for imitation.

9. What are the phonological or linguistic-based approaches?

The linguistic-based approaches, or phonologically based interventions, emphasize the contrastive use of sounds to create meaning. The focus is on the function of phonemes rather than on accurate production of phonemes. The basis of a phonological disorder is difficulty with the function of sounds and with the organization of the sound system. In contrast, an articulation disorder represents a motor speech-related difficulty with the accurate production of phonemes. Therapy for phonological disorders focuses on organizing the child’s sound system so that sounds are produced in the appropriate context. Consider the following example:

“Sara is 4 years, 7 months of age. When someone asks her age, she proudly states [por] for four. However, she will also call her dog Finn to come in from the backyard yelling [fɪn]. In this simple, brief example, Sara has demonstrated the ability to produce the [f ] phoneme. However, she is not demonstrating the ability to utilize the phoneme [f ] in the appropriate context when calling her dog. Therefore, her difficulty is not in the motor skills needed for the accurate production of [f ], but rather using the sound contrastively to create the intended meaning according to the phonological rules of her native language. A linguistic-based approach, or a phonological-intervention approach, would be appropriate to help Sara learn the function of sounds and the phonological rules of her language.” (Koch, 2019, p. 256).

10. What are the primary principles of the phonological or linguistic-based approaches?

Phonological-intervention approaches are based on the following principles:

- Intervention focuses on the child’s speech sound system (Gierut, 2005, 2007; Stoel-Gammon & Dunn, 1985)

- Targets for intervention are selected to emphasize production features that will effect changes to sound classes and result in system-wide change and generalization in a child’s sound system (Gierut, 2001, 2005, 2007; Stoel-Gammon & Dunn,1985)

- Intervention begins at the word level to facilitate the functional use of speech sounds to create meaning (Lowe, 1994; Weiner, 1981)

- Intervention guides children to learn to utilize the phonological rules of the language (Lowe, 1994)

- Strategies will include conversational repair based on a clinician request for clarification due to semantic confusion and breakdown (Weiner, 1981)

11. What are minimal pairs?

Historically, the minimal pairs approaches emphasize the use of word pairs that differ by one phoneme to highlight the change in meaning that is a result of the error (Barlow & Gierut, 2002). Thus, the error signals a deficit in knowledge of the function of sounds to result in the intended meaning. For example, a child may say [ti] for tea, but also for see. The words are produced as homonyms and the phoneme [s] is not used contrastively to establish the different meaning represented in the word see. The minimal pairs approach was originally conceptualized to contrast the error and the target (Weiner, 1981). The word pairs differed by one phoneme. Using the present example, a child that consistently substitutes [t] for [s], other minimal word pairs that might be used in therapy could include: toe/sew, two/sue, tap/sap, team/seam, toon/soon. The error and the target are used contrastively in the minimal word pairs and highlighted to the child the need to produce a different phoneme to eliminate the homonymy. This is the original application of the concept of minimal pairs as proposed by Weiner (1981).

12. What is all this I’m hearing about the “contrast approaches”?

The minimal pair approach originally described by Weiner (1981) has been implemented in a variety of ways by researchers (Baker, 2010; Crosbie, Holm & Dodd, 2005; Elbert, Dinnsen, Swartzlander, & Chin, 1990; Gierut, 1990; Gierut, 1992; Williams, 2000a). This minimal pair approach has served as the basis or foundation from which other contrastive therapeutic approaches have evolved. Primarily, the different approaches focus on how targets are selected for the minimal pairs. Each approach establishes minimal pairs as the treatment targets. The criteria for how the word pairs differ is what makes each of the approaches unique (Barlow & Gierut, 2002). Rather than contrasting the error production with the target, each contrast approach guides the selection of target word pairs according to different criteria.

Phonemes are comprised of features. Different combinations of features result in different phoneme realizations. Therefore, it is the combination of features of the phonemes that served to differentiate and create contrasts among phonemes. Phonemes are characterized and categorized according to the acoustic and production features called distinctive features, and according to the features of place of articulation, manner of articulation, and voicing. The features of place, manner, and voicing are considered to be nonmajor class features. Major class features for categorizing vowels and consonants include: sonorants and obstruents. Major and nonmajor classifications are utilized in target selection for the maximal oppositions contrast approach.

Examination of the number of feature differences that may be represented in minimal pairs also contributed to the distinction of different approaches that emphasized how sounds differed in minimal pairs. For example, the word pair of key and tea differ by one feature, place of articulation. The phoneme [k] is a velar, stop, and is voiceless. The phoneme [t] is an alveolar, stop, and is voiceless. Thus, they differ only by one feature, place of articulation. The word pair of my and buy differ by one feature, manner of articulation. The phoneme [m] is a bilabial, nasal, and is voiced. The phoneme [b] is a bilabial, stop, and is voiced. Thus they differ by one feature, manner of articulation. The word pair of two and do differ by one feature, voicing. The phoneme [t] is an alveolar, stop, and is voiceless. The phoneme [d] is an alveolar, stop, and is voiced. Thus, they differ by one feature, voicing. Extending this exercise in comparing the number of feature differences represented in minimal pairs, let’s examine the minimal pair of keys and cheese. The two words differ by one phoneme. The phoneme [k] is a velar, stop, and is voiceless. The phoneme [ʧ] is a palatal, affricate, and is voiceless. Therefore, the phonemes differ across the two features of place and manner of articulation. One last set of minimal pairs is presented for consideration. The words go and sew are minimal pairs as they differ by one phoneme. Closer examination reveals that they differ across three features. The phoneme [g] is a velar, stop, and is voiced. The phoneme [s] is an alveolar, fricative, and is voiceless. Therefore, not all minimal pairs are the same. Thus, consideration must be made for how the phonemes in minimal pairs are different.

13. What is the minimal oppositions contrast approach?

Minimal oppositions contrast approach: targets are contrasted that differ by one feature difference.

14. How are targets selected for minimal oppositions contrast approach?

A place-manner-voicing analysis is conducted among the substitution errors noted during the assessment. The place-manner-voice analysis provides additional information related to the number of feature differences among the wide range of substitutions demonstrated by a child. Intervention targets for minimal oppositions approach would be selected from the substitution errors that are characterized by one feature difference. By doing so, the target would be contrasted with the substitution error, consistent with the original format of minimal pairs intervention.

15. What is the multiple oppositions contrast approach?

The multiple oppositions approach is an adaptation of minimal pairs. Multiple oppositions is a contrastive approach that targets several error sounds that are represented in a collapse of phonemes (Williams, 1991; 2000b; 2003; 2005a, b, c). A collapse of phonemes is identified when a child substitutes one sound across several different target sounds. For example, if a child substitutes the phoneme [t] for [k, s, ʃ, ʧ], the words two, coo, sue, shoe, chew, would all be produced as [tu]. Thus, the [t] substituted for the target phonemes of [k, s, ʃ, ʧ] represents a collapse of phonemes. The strategy for targeting several phonemes from a collapse is designed to facilitate the most learning about the phonological system. The underlying premise is that the child’s system requires systematic reorganization through contrasting the error with several of the target sounds, thus creating multiple sets of minimal pairs.

Williams (2010) proposed that children with significant speech sound disorders, characterized by multiple phoneme collapses, have deficits in both the motor aspects of articulation as well as the phonemic difficulties related to contrastive use of phonemes to create meaning. In other words, the deficits lie in both the form (production) and function of sound system. Thus, the multiple oppositions approach addresses skills in both areas.

16. How are intervention targets selected for the multiple opposition contrast approach? Intervention targets for the multiple opposition approach would be selected from the substitution errors that are represented in a phoneme collapse. In a phoneme collapse that involves up to four target phonemes, a clinician may decide to utilize all target phonemes in the treatment target words. If a child is demonstrating a significant collapse that involves more than four target phonemes, selecting phonemes across different phoneme classes is suggested (Williams, 2005c). For example, an extensive collapse might be represented in a child that substitutes [b] for [d, k, g, m, n, s, l, r, ʃ, ʧ, j, h]. Rather than attempt to develop a list of target words for this extensive collapse, phonemes are selected to represent different phoneme classes. As previously discussed, the contrast approaches promote generalization across sound classes, thus each individual phoneme in the collapse does not need to be targeted. Using the significant collapse where the child substitutes [b] for [d, k, g, m, n, s, l, r, ʃ, ʧ, j, h], the collapse represents multiple errors related to each of the phoneme classes of stops, nasals, fricatives, liquids, glides, and affricates. Targets for intervention might include [b, d, m, s, ʃ] and would result in a target word set of boo, do, moo, sue, shoe. This set of minimal pair target words represents the phoneme classes of stops, nasals, and fricatives (Koch, 2019).

17. What is the maximal oppositions contrast approach?

The maximal oppositions approach is an adaptation of minimal pairs. Maximal oppositions approach emphasizes the specific ways in which contrasted word pairs are different. Gierut (1990, 1991, 1992) proposed that minimal word pairs can be different along three different dimensions: major class features, distinctive features, and whether the sound is in the child’s phonetic inventory. Major class categorizes the nature of the feature differences by making a distinction between the sonorant and obstruent sounds. Thus, /s/ as an obstruent would different according to major class features from /r/ which is a sonorant. The two words in a contrasted minimal pair may also be different according to maximal feature distinctions by the number of distinctive features by which the two sounds are different. As an example, /k/ and /l/ differ by 8 distinctive features. Another related dimension that can be utilized to examine the nature and extent of distinction between two contrasted phonemes is place-manner-voicing. As such, phonemes may differ in one- two- or three- production features. One or both sounds contrasted in the minimal pair set may also be sounds in the child’s phonetic inventory. Alternately, the child may not demonstrate knowledge of the two contrasted sounds and the sounds are not present in the child’s phonetic inventory. When sounds not in the child’s inventory are contrasted, this is referred to as the empty set.

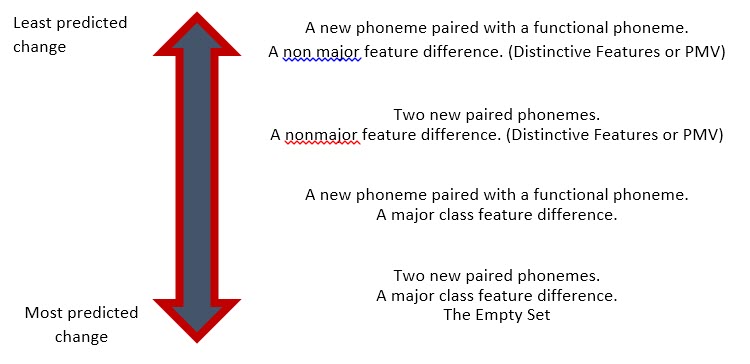

The strategy for selecting target word pairs that are maximally different is to facilitate more overall change to the child’s speech sound system. By emphasizing greater salient differences in sounds through greater feature differences, intervention may result in more change in the acquisition of the features of the contrasts and more generalization to other sounds (Gierut, 1989, 1990). The strategy for targeting one or two unknown sounds that are not in the child’s inventory is also designed to facilitate the most learning about the phonological system. Additionally, targeting two new sounds, not in the child’s phonetic inventory, the empty set, results in more generalization to untreated sounds. Thus, in maximal oppositions, there are several different combinations of the factors that are considered for target selection. The following figure illustrates the various ways that the factors can be combined and how these fall along a continuum of predicted change to the child’s phonological system.

Figure 1. Continuum of predicted change to a child’s phonological system.

The theoretical foundation for maximal oppositions is that emphasizing the feature differences between sounds prompts change in the child’s phonological system. This is in contrast to the functional nature of contrasting meaning differences in the other minimal pairs approaches (Geirut, 1991).

18. How are intervention targets selected for the maximal oppositions contrast approach?

The analysis begins with categorizing among major classes: sonorants and obstruents. The feature analysis utilizing place-manner-voicing provides additional information related to the extent of feature differences among error phonemes or phonemes that are not in the child’s phonetic inventory. These are the nonmajor features. The more differences between phonemes along the dimensions of PMV, the more maximally opposed the word pairs. A distinctive feature analysis can also be completed. Intervention targets for the maximal opposition approach fall along a continuum of degree of maximal opposition, according to the degree of expected change in the child’s phonological system as a result of intervention (Ruscello, 2008). See the figure above.

19. How would a behavioral goal be written to reflect the contrast approaches?

- The child will produce the phonemes [t, s] in minimally opposed word pairs at the word level in response to pictures with 90% accuracy over 2 consecutive sessions.

- The child will produce and contrast the phoneme [b] with the phonemes [d, m, s, ʃ ] in minimal pair treatment sets using the multiple oppositions approach at the word level in response to pictures with 90% accuracy over 2 consecutive sessions.

- The child will produce the phonemes /k, l/ in maximally opposed, empty set word pairs at the word level in response to pictures with 90% accuracy over 2 consecutive sessions.

20. Can you give some examples of targets/target words for each of the contrast approaches?

Using the goals provided above, the following could be potential targets:

- Minimal Oppositions Contrast: two-Sue, tea-sea, toe-sew, tack-sack, tie-sigh

- Multiple Oppositions Contrast Approach: boo-do-moo-Sue-shoe, bee-dee-me-see-she

- Maximal Oppositions Contrast Approach: key-Lee, cake-lake, cook-look, kite-light, coop-loop

References

Barlow, J.A. & Gierut, J.A. (2002). Minimal pair approaches to phonological remediation. Seminars in Speech and Language, 23(1), 57-67.

Bernthal, J.E., Bankson, N.W., & Flipsen, P.J. (2017). Articulation and phonological disorders: Speech sound disorders in children. Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc.

Bleile, K.M. (2006). The late eight. San Diego, CA: Plural Publishing.

Fish, M. (2011). Here’s how to treat childhood apraxia of speech. San Diego, CA: Plural Publishing.

Gierut, J.A. (1989). Maximal opposition approach to phonological treatment. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 54, 9-19.

Gierut, J.A. (1990). Differential learning of phonological oppositions. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 33, 540-549.

Gierut, J.A. (1991). Homonymy in phonological change. Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics, 5, 119-137.

Gierut, J. (1992). The conditions and course of clinically induced phonological change. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 35, 1049-1063.

Gierut, J. (2001). Complexity in phonological treatment: Clinical factors. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 32, 229-241.

Gierut, J. (2005). Phonological intervention: The how or the what? In A.G. Kamhi & K.E. Pollock (Eds.), Phonological disorders in children: Clinical decision making in assessment and intervention. (p. 201-210). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes.

Gierut, J. (2007). Phonological complexity and language learnability. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 16(1), 6-17.

Howell, J. & Dean, E. (1994). Treating phonological disorders in children: Metaphon: Theory to practice. (2nd Ed.). London, UK: Whurr.

Jakielski, K.J. (2011). Sarah: Childhood apraxia of speech: Differential diagnosis and evidence-based interventions. In S.S. Chabon & E.R. Cohn (Eds.). The communication disorders casebook: Learning by example. (p. 173-184). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

Koch, C. (2019). Clinical Management of Speech Sound Disorders: A Case-Based Approach. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett, Inc.

Lowe, R.J. (1994). Phonology: assessment and intervention application in speech pathology. Baltimore, MD: Williams and Wilkins.

McLeod, S. & Baker, E. (2017). Children’s speech: An evidence-based approach to assessment and intervention. Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc.

McLeod, S. & Crowe, K. (2018). Children’s consonant acquisition in 27 languages: A cross-linguistic review. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 27, 1546-1571.

McLeod, S. & Singh, S. (2009). Speech sounds: A pictorial guide to typical speech sounds. San Diego, CA: Plural Publishing.

Ruscello, D. (2008). Treating Articulation and Phonological Disorders in Children. St. Louis, MO: Mosby.

Secord, W.A. (1989). The traditional approach to treatment. In N. Creaghead, P.W. Newman, & W.A. Secord (Eds.), Assessment and remediation of articulatory and phonological disorders (p. 129-158). New York, NY: Macmillan.

Stoel-Gammon, C. & Dunn, C. (1985). Normal and disordered phonology in children. Baltimore, MD: University Park Press.

Strand, E.A. & Skinder, A. (1999). Treatment of developmental apraxia of speech: Integral stimulation methods. In A. Caruso & E.A. Strand (Eds.). Clinical management of motor speech disorders in children. (p. 109-148). New York, NY: Thieme.

Strand, E. & McCauley, (2008). Differential diagnosis of severe speech impairment in young children. The ASHA Leader. www.asha.org/Publications/leader/2008/080812/f080812a.htm

Strand, E.A., Stoeckel, R. & Bass, B. (2006). Treatment of severe childhood apraxia of speech: A treatment efficacy study. Journal of Medical Speech-Language Pathology, 14(4), 297-307.

Weiner, F.F. (1981). Treatment of phonological disability using the method of meaningful minimal contrast: Two case studies. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 46, 97-103.

Williams, A.L. (1991). Generalisation patterns associated with least knowledge. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 34, 722-733.

Williams, A.L. (2000a). Multiple oppositions: Case studies of variables in phonological intervention. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 9, 289-299.

Williams, A.L. (2000b). Multiple oppositions: Theoretical foundations for an alternative contrastive intervention approach. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 9, 282-288.

Williams, A.L. (2003). Speech disorders resource guide for preschool children. Clifton Park, NY: Delmar Learning.

Williams, A.L. (2005a) Assessment, target selection, and intervention: Dynamic interactions within a systemic perspective. Topics in Language Disorders, 25(3), 231-242.

Williams, A.L. (2005b). From developmental norms to distance metrics: Past, present, and future direction for target selection practices. In A.G. Kamhi & K.E. Pollock (Eds.), Phonological disorders in children: Clinical decision making in assessment and intervention (p. 101-108). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes.

Williams, A.L. (2005c). A model and structure for phonological intervention. In A.G. Kamhi & K.E. Pollock (Eds.), Phonological disorders in children: Clinical decision making in assessment and intervention (p. 189-199). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes.

Citation

Koch, C. (2019). 20Q: Speech Sound Disorders: "Old" and "New" Tools. SpeechPathology.com, Article 20029. Retrieved from www.speechpathology.com