From the Desk of Ann Kummer

As most of you know, a previous edition of 20Q was From Kanner to DSM 5: Autism from an SLP Lens – Part I. In that article, Dr. Theresa Bartolotta answered questions regarding how theories of the underlying cause of ASD have evolved since autism was first described by psychiatrist Leo Kanner in 1943. If you have not read that article, please do. It is worth your time!

It is now my pleasure to present to you the much anticipated Part II of that article. In this part, Dr. Bartolotta answers questions regarding the paradigm change from autism as a single disorder to that of a spectrum disorder. She also answers questions regarding some of the issues with this change, including its impact on the Asperger’s community.

Dr. Theresa Bartolotta is Professor of Speech-Language Pathology at Monmouth University in New Jersey, where she teaches graduate courses in Research Methods, Pediatric Language Disorders, Autism, and Speech Sound Disorders. Her research interests are interventions for persons with complex communication disorders, including Rett syndrome, Down syndrome, and autism. As noted previously, Dr. Theresa Bartolotta has over 30 years of clinical experience. She has published articles and presented widely on communication intervention with this population. Therefore, we are so fortunate to be able to learn from her vast knowledge on this topic.

Now...read on, learn and enjoy!

Ann W. Kummer, PhD, CCC-SLP, FASHA

Contributing Editor

20Q: From Kanner to DSM-5 - Autism from an SLP Lens, Part II

Learning Outcomes

After this course, readers will be able to:

- list the criteria for Autism Spectrum Disorder in DSM 5.

- describe how the new criteria have impacted the diagnosis of Asperger’s Syndrome, Rett Syndrome and Childhood Disintegrative Disorder.

describe factors that influence the increased prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorders in the US.

1. What are some of the factors that led to reconceptualizing autism?

With the discovery of the genetic cause of Rett Syndrome (RTT) in 1999 a discussion ensued that Rett syndrome should be removed from the spectrum and from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). Additional criticism of the description of the spectrum in 1994 concerned the criteria for Asperger’s Disorder and PDD-NOS. A number of individuals with Asperger’s were described as “high-functioning”, and those with PDD had what was considered by many to be a “milder” form of autism. Criteria for these two disorders were felt to be too flexible and use of subjective terminology in the description of each, such as “marked impairments” in a behavior, led to wide variability in diagnostic practices. It was not uncommon for a child to receive a diagnosis of PDD-NOS before age three, and then, as he/she received interventions and began to improve in functioning, be re-labeled as having Asperger’s. Educators and families alike found that the label PDD-NOS was often given to young children suspected of being on the autism spectrum, in an effort to avoid the stigma still accompanying the term “autism”.

2. What were the criteria for the spectrum?

In the DSM IV, which was used by medical professionals and clinicians from 1994-2013, the following behaviors were required for a diagnosis of autism:

- At least two impairments in social interaction

- At least one impairment in communication

- At least one “restricted, repetitive, and stereotyped pattern of behavior, interests, and activities"

- A delay or abnormal functioning is observed in social interaction, language used as social communication, or symbolic/imaginative play prior to age 3. (American Psychiatric Association, 1994)

3. What about children with a milder presentation?

Children with “subthreshold” symptoms who did not meet all of the criteria for autism, but presented with both social and communication problems, as well as restricted or unusual behaviors, were given a diagnosis of PDD-NOS. However, many children were given this diagnosis initially while quite young. Later, as their symptoms solidified, many received a diagnosed of autism or Asperger’s.

4. What are Rett syndrome (RTT) and Childhood Disintegrative Disorder (CDD)?

These disorders were included in the DSM IV because of individuals with these disorders have challenges in the social and communication domains, but each is very different from autism. Individuals with RTT are almost exclusively female and undergo a loss of skills in motor development and communication, usually before age two years. They often have significant problems with walking and few develop functional hand skills. The identification of the genetic cause of RTT, a mutation in the MeCP2 gene on the X chromosome, provided evidence of a biological marker and enabled researchers to develop a core set of criteria to improve accuracy and consistency of diagnostic practices (Neul et al., 2010). In contrast, CDD has a later onset than RTT or autism, usually emerging between the child’s second and third birthdays. Children with CDD have a severe regression in at least two domains of development and are often severely affected. CDD is quite rare, occurring in approximately 1 child in 100,000 (Matson & Mahan, 2009).

5. Where did Asperger’s Disorder come from?

In 1944 Hans Asperger, a contemporary of Kanner, described a unique set of individuals with these characteristics: specific challenges in social understanding, but higher cognitive skills and overall functioning; i.e. their social problems were significant despite adequate verbal abilities. Asperger wrote his paper in German and his work was not available in English until the 1990’s (Frith, 1991) which accounts for the delayed adoption of the syndrome outside of Germany. Since the 1990’s a great debate has raged regarding whether Asperger’s is truly distinct from autism. A popular theory is that Asperger’s is actually a set of symptoms displayed by higher-functioning individuals with autism. In DSM-IV, Asperger’s was clearly identified as a separate disorder with specific criteria. However, many clinicians have been challenged to distinguish people with Asperger’s from those with PDD-NOS or even classic autism. They seem so similar and many clinicians struggled to distinguish the disorders. The key clinical characteristic seemed to be acquisition of language, as one of the criteria for Asperger’s was no significant delay in language development (APA, 2000).

6. Is a “delay in language” useful in distinguishing autism from Asperger’s?

There is so much variation in the language development in typically developing children that relying on the timing of first words as a key feature distinguishing between autism and Asperger’s is a weak premise. There are numerous reports of children who are late talkers who catch up to their peers and do very well. Conversely, a child may use their first words at one year of age, and then display significant learning problems later in childhood. Also, early milestones for language development emphasize semantics and syntax to the exclusion of pragmatics. The important role of development of the social aspect of language, such as initiating and maintaining conversations, is not always thought of in the early years. Hence, many children with challenges in the social use of language, and who may end up with symptoms that are consistent with what Hans Asperger described so many years ago, may be missed in the early years.

7. Is Asperger’s really different from autism?

Questions about whether Asperger’s is clinically a distinct disorder have persisted for decades and continue to present day (Howlin, 1987). Many clinical researchers view Asperger’s Disorder as a different level of severity of classic autism, not as a separate disorder. The new criteria place a strong emphasis on the social use of language and the consolidation of social behaviors and language behaviors into one domain. These modifications may allow those with milder social challenges to meet the criteria for services, thus alleviating many concerns regarding individuals previously diagnosed with PDD-NOS or Asperger’s Disorder.

8. When was DSM 5 published?

The Diagnostics and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth edition, (DSM 5), was released in 2013 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) after a twelve-year process. This newest edition created controversy regarding how autism was defined and described. The Neurodevelopmental Disorders group, composed of subject-matter experts from a variety of fields, attempted to address the persistent issues about the DSM-IV label for autism. In this new edition the working group implemented a new severity rating to quantify the degree of impairment. The hope is that these new criteria provide clarity and enable early and consistent diagnosis. The average age of diagnosis across the US is 4 years, and professionals receive training in recognizing early signs. The “First Signs” project has raised awareness of the disorder and the value of early diagnosis among parents and professionals across the country.

9. What’s new in DSM 5?

Adults who have a history of symptoms of ASD can now receive a diagnosis at any age. Additionally, the terminology for how we discuss and describe cognitive impairment or mental retardation has been changed and is now described as intellectual impairment.

What is especially significant now is that autism is conceptualized as a single disorder – called Autism Spectrum Disorder. The term PDD is no longer used. Rett syndrome, Asperger’s Disorders, and Childhood Disintegrative Disorder are no longer part of the spectrum. There is now one unifying term that is characterized by deficits in two fundamental domains. The distinction between social challenges and communication have been removed and the features combined into one category. This marks an attempt to address the challenge in adopting a standardized measurement for clinically useful measures of severity. In the DSM 5, autism is described with clinical characteristics and impact on quality of life.

10. Is it true that impact on quality of life is a new way to look at autism?

Speech-language clinicians and other health care providers are asked to examine the impact of disability on an individual’s quality of life and demonstrate how interventions improve daily functioning. The World Health Organization has adopted a listing of all diseases and disorders, known as the International Classification of Diseases and another scale, the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) which classifies global disability based on impact on functioning (World Health Organization, 2013). The ICF considers how a disorder affects the person in their life – examine body functions and structure, and then considers activity (what a person can do) and participation (how they can function in the world). For example, the types of “occupations” individuals can engage in – such as work, or hobbies, are considered. Additionally, the level of independence a person has for activities of daily living are also described.

11. What’s been the impact of DSM 5 on persons with Asperger’s disorder?

With the publication of DSM 5, there was great concern that a number of individuals with an Asperger’s diagnosis would lose eligibility for services. This concern was somewhat understandable, especially in the years leading up to publication, as there was a question about how the new criteria would apply to individuals who had previously qualified under the ASD umbrella as meeting criteria for Asperger’s disorder. The new criteria are more specific than the criteria under DSM-IV which hopefully will enable clinicians to better differentiate ASD from other disorders that result in communication impairment, such as language disorders, intellectual deficits, and anxiety disorders (Huerta et al, 2012). However, the concern remains that many individuals with Asperger’s may no longer meet the criteria for ASD. This issue is under study at present; individuals who present with challenges in communication and social behaviors must receive the services they need to be as independent as possible and achieve the highest quality of life. Clinicians who serve on diagnostic teams must work to conduct assessments in the most naturalistic environment as possible, using well-established tools, in order to obtain the most accurate and relevant assessment data as possible.

12. Can you describe the diagnostic criteria and provide examples?

Sure! Persons meeting the criteria for Autism Spectrum Disorder must demonstrate the challenges in the following two domains:

- Persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction across multiple contexts

- Restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities.

For both domains, the symptoms must have been, or currently, present in the early developmental period. For example, if an individual has a history of deficits in either of both of those areas as a young child, but no longer displays symptoms explicitly as an adult, they may still fit the criteria for diagnosis. The key issue for valid diagnosis is there must be reliable evidence that the symptoms were present during the very early developmental period, which is usually considered to be during the first three years of life. Additionally, the symptoms must cause clinically significant impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. Though the ICF model is not explicitly stated in the criteria, what is of note is the language about impact on function which is an attempt to establish a threshold where symptoms express as a disorder.

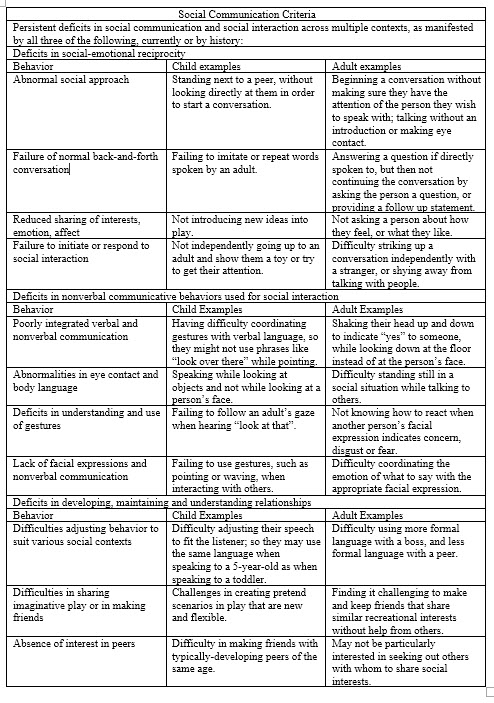

13. What are examples of behaviors that meet the Social Communication criteria?

The table below provides a listing of the Social Communication criteria for autism, along with examples of behaviors that might be observed in children and adults. The list of behaviors is not meant to be exhaustive, but rather provide typical examples that might be seen in varying levels of severity.

Figure 1. Social communication criteria. (Adapted from DSM 5, American Psychiatric Association, 2013. Click here for larger version of figure 1.)

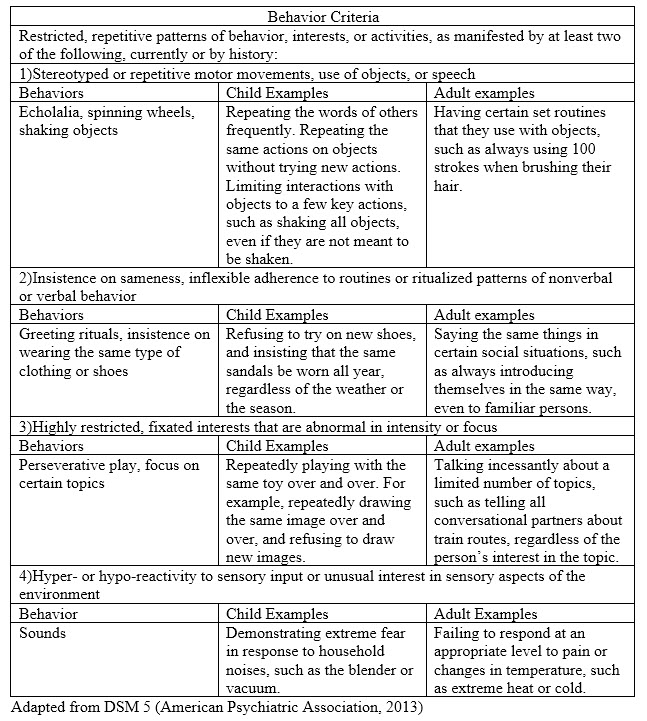

14. What about examples for the behavior criteria requirement?

The table below provides a listing of the behavior criteria for autism, along with examples of behaviors that might be observed in children and adults. As with the social communication criteria, the list in the table provides typical examples that might be seen in varying levels of severity. These behaviors may not be present in individuals on your caseload.

Figure 2. Behavioral criteria. (Adapted from DSM 5, American Psychiatric Association, 2013. Click here for larger version of figure 2.)

15. Does an individual have to exhibit all of the criteria in each domain?

No. An individual must display evidence of all three of the Social Communication criteria, and two of the four Behavior Criteria. The examples given in the tables above are examples only – the behaviors must not be observed exactly as stated. Accurate diagnosis requires the efforts of experienced clinicians who are familiar with the criteria and how to assess each domain. SLPs who serve on diagnostic teams, or who provide treatment to persons with ASD, may want to seek training in the new criteria so that they provide the best, most accurate services to the individuals with whom they work.

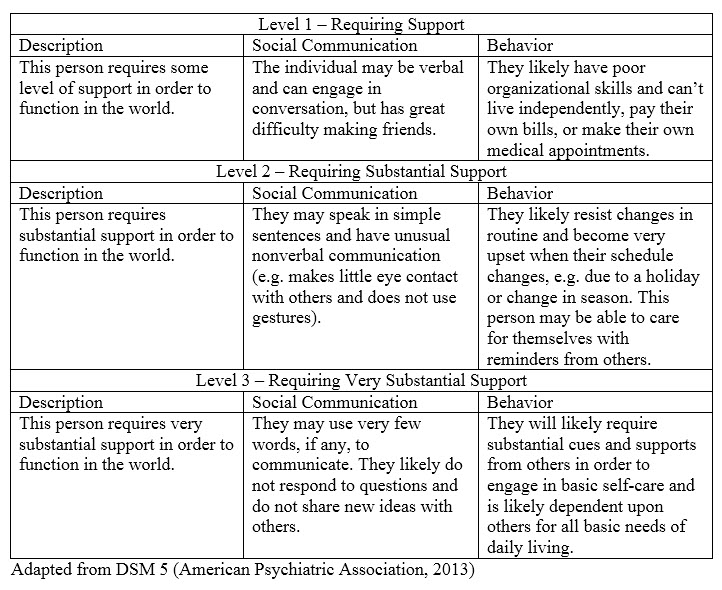

16. How is severity assessed, and what are some examples of behaviors at each level?

There are three levels of severity and they vary based on the level of support needed by the individual to function in society. Severity should be assessed for each domain separately, so for example, clinicians will make an independent assessment of a person’s social communication skills as well as their behavior, interests and activities. The next table contains a description of the levels of severity and examples for each domain at all three levels.

Figure 3. Levels of severity. (Click here for larger version of figure 3.)

17. The prevalence of autism has increased so much in recent years – what are some of the reasons why?

There are a number of theories about the large increase in the number of cases of autism in recent years. It is likely that improved awareness of ASD has contributed to earlier referrals of children to specialists. There is speculation about the impact of the environment and dietary problems (e.g. allergies to gluten or dairy), but none of these potential influences are supported by evidence. There is concern that overdiagnosis is occurring far too often and is one of the contributing factors to the “epidemic” of cases (Prizant, 2012). In his article on the impact of misdiagnosis, Prizant makes a strong argument that children with language or communication problems, along with challenges that are associated with autism (e.g. anxiety, impulsivity, behavior problems) are being incorrectly diagnosed with ASD (2012).

18 What role can speech-language pathologists play in helping to correctly identify children with ASD?

SLPs are uniquely qualified to assist as part of a diagnostic team in helping to accurately identify children with ASD. For example, using standardized assessments, along with language sample analysis, SLPs can assist in determining if a child has a developmental language disorder with other associated behaviors, or if the child’s language behaviors are fully consistent with ASD criteria. As with any specialized area of practice, an SLP who participates in the assessment and diagnosis of a person with autism should have the appropriate education and training to carry out that role (American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, 2016).

19. What is the impact of the new DSM 5 criteria on diagnosis and clinical practice?

As of this writing, the effectiveness of the DSM 5 in improving clinical practice is under review. Evident strengths are the consolidation of the social and communication domains and the allowance for diagnosis to be made based on historical reporting. Alignment with the ICF model will allow for consistency across the global context, hopefully limiting confusion with different terminology. A recent study comparing cases of PDD to DSM 5 criteria found that most individuals who received a diagnosis of PDD under DSM-IV would continue to be eligible for an ASD diagnosis using DSM 5 criteria (Huerta et al, 2012). This is good news for individuals with a PDD diagnosis. The concern about what to do with those carrying an Asperger’s diagnosis remains; new diagnostic criteria should be inclusive of those with similar characteristics. These individuals and their families should not feel marginalized; though it appears that was not the intent of the Working Group, that may be an unwanted outcome as efforts are made to standardize clinical practice.

20. What should SLPs keep in mind as they work with their clients?

A final note for clinicians – we treat people, not labels. The value of a good diagnosis cannot be minimized; it can set the path for good, appropriate, effective and efficient treatment. However, speech-language pathologists evaluate communication, and our treatments should be individualized to address the unique needs of an individual, often regardless of the diagnosis. Something to remember as we continue exploring the complex but fascinating world of autism.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

American Psychiatric Association (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. (4th ed. text rev.). Washington, DC: Author.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. (Fifth ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2016). Code of ethics [Ethics]. Available from www.asha.org/policy.

Frith, U. (1991). Autism and Asperger syndrome. New York: Cambridge University Press. (2006). Autistic behavior in children with Fragile X syndrome: Prevalence, stability, and

the impact of FMRP. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 140A(17), 1804-1813.

Howlin, P. (1987). Asperger syndrome: Does it exist and what can be done about it? In Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Specific Speech and Language

Disorders in Children. London: AFASIC.

Huerta, M., Bishop, S.L., Duncan, A., Hus, V., & Lord, C. (2012). Application of DSM-5 criteria for autism spectrum disorder to three samples of children with DSM-IV diagnoses of pervasive developmental disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 169(10), 1056-1064.

Neul, J.L., Kaufman, W.E., Glaze, D.G., Christodoulou, J., Clarke, A.J., Bahi-Buisson, N., Leonard, H., Bailey, M.E.S., Schanen, N.C., Zappella, M., Renieri, A., Huppke, P., & Percy, A.K. (2010). Rett syndrome: Revised diagnostic criteria and nomenclature. Annals of Neurology, 68(6), 944-950.

Prizant, B. M. (Summer, 2012). One the diagnosis and misdiagnosis of autism spectrum disorder. Autism Spectrum Quarterly, 53-60.

World Health Organization (2013). How to use the ICF: A practical manual for using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Exposure draft for comment. Geneva: Author. [Retrieved from: http://www.who.int/classifications/drafticfpracticalmanual.pdf]