From the Desk of Ann Kummer

In the United States, July and August are typically the hottest months of the year. So far, this year has been no exception other than it has been exceptionally hot! I suppose it’s fitting, therefore, to have an exceptionally hot topic featured in our July and August editions of 20Q. That topic, of course, is autism spectrum disorders.

We are so fortunate to have Dr. Theresa Bartolotta, an expert in autism spectrum disorders (ASD), to help us to better understand this very perplexing disorder through this two part series. As an SLP with over 30 years of clinical experience, Dr. Bartolotta specializes in communication disorders in children with significant disabilities. Her primary research interests are in communication impairment in autism spectrum disorders, including Rett syndrome. She has published articles and presented widely on communication intervention with this population.

In this July edition (Part I), Dr. Bartolotta answers questions regarding how theories of the underlying cause of ASD have evolved since autism was first described by psychiatrist Leo Kanner in 1943. In the August edition (Part II), Dr. Bartolotta answers questions regarding the paradigm change from autism as a single disorder to a spectrum disorder. She also answers questions regarding some of the issues with this change, including its impact on the Asperger’s community.

We have so much yet to learn about ASD and how it affects individuals with this diagnosis. These two articles will certainly help you to have a better understanding of this spectrum disorder and how our knowledge of it has evolved in the last 75 years since it was first described.

Now...read on, learn and enjoy!

Ann W. Kummer, PhD, CCC-SLP, FASHA

Contributing Editor

20Q: From Kanner to DSM 5 - Autism from an SLP Lens, Part I

Learning Outcomes

After this course, readers will be able to:

- list the criteria Kanner used to first describe autism in 1943.

- describe how models of diagnosis and causality have evolved over the decades.

- describe current trends in autism.

1. Why is the history of autism relevant to speech-language pathologists?

Autism has fascinated and perplexed health care professionals for decades and been the subject of intense debate about causality and effective treatments. Because of decades of scrutiny, there are now clues to potential causes, diagnosis is made early and with precision, there is a growing body of evidence regarding effective treatments, and there are services to help individuals integrate into society.

Autism is now one of the most commonly occurring developmental disorders in the U.S., with approximately 1 in 59 children diagnosed with the disorder (Baio et al., 2018). Communication difficulties are part of the core features of the disorder, so speech-language pathologists (SLPs) play a key role in both diagnosis and treatment planning for individuals with autism. Understanding the historical context of autism can (hopefully) help us avoid mistakes of the past and provide the best treatment to individuals with autism and their families across the lifespan.

2. So what’s happened over the last 80 years?

Several key points emerge as the history of autism is described in the paragraphs below: 1) the cause remains unknown, though there are clues to the neurobiological basis; 2) key characteristics described by Kanner in the 1940’s are the core deficits described today; and 3) the incidence of the disorder has skyrocketed, in parallel with increased awareness and improved diagnostic practices. There are different theories to explain the reasons for the increase, and we will dive into those in Part II.

Autism has been a profound challenge for researchers over the years. Is it one disorder with varying presentations? Or is it one term for several disorders sharing core features with disparate causes? Is it a disease entity? A biological syndrome? Or a collection of symptoms due to a group of heterogeneous psychosocial influences? In the following paragraphs we’ll examine the growth of knowledge over time, point out what is known, and what we do not yet understand.

3. How have theoretical models changed over time?

From the time autism was first described in 1943 by psychiatrist Leo Kanner, the world has been fascinated by this puzzling disorder. Changes in how autism has been conceptualized have paralleled advances in psychiatry and psychology. Initially autism was described as a psychiatric disorder. As behaviorism evolved in the 1960’s researchers hypothesized that autism had a behavioral origin. As psychology and neurology matured, and with more research data and clinical experience, theories of causation became clarified. There was consensus of what autism was not (e.g. not schizophrenia, not a mental illness).

4. What about therapy?

Ideas about effective treatments have evolved as our understanding of the disorder has shifted. Behavioral interventions became popular in the 1960’s, and as social and pragmatic approaches to treating learning challenges became popular, these interventions were studied. With educational reforms in the 1970’s, services and learning programs for children with disabilities became widely available. As these individuals aged and became adults living in the community there was a corresponding increase in programs for adults with autism age 21 and over. With improved outcomes and integration of individuals with ASD into society, the larger world has adjusted. Universities are developing programs to support students with autism, and employers are increasingly willing to make accommodations for employees with autism.

5. When and how was autism first described?

Autism was first formally described in 1943 by Leo Kanner, an American psychiatrist. However, there are earlier accounts of individuals with signs of autism. It is believed that Viktor, the ‘Wild Boy of Aveyron’ who was studied by the physician Itard in the 1800’s had autism (Trevarthan, Aitken & Papoudi, 1996). In their book about an unusual Scottish landowner from the 1700’s whose marriage was annulled because of mental incapacity, Houston and Frith provide evidence that the man’s behaviors resembled autism (2000). These accounts illustrate how autism can be recognized in different cultural contexts and eras and is influenced little by cultural or social norms.

In his article entitled Autistic Disturbances of Affective Contact, Kanner wrote about several children in his practice who presented with a condition that “differs so markedly and uniquely from anything reported so far, that each case merits-and, I hope, will eventually receive-a detailed consideration of its fascinating peculiarities” (1943, p. 217). Kanner described 11 children (eight boys, three girls) between the ages of 2-11 years presenting with varying degrees of language, motor, social and behavioral challenges. Common to all was a profound and fundamental “inability to relate themselves in the ordinary way to people and situations from the beginning of life” (p. 105). One of the key criteria Kanner used to distinguish autism from other disorders, such as schizophrenia, was the early onset of symptoms. To meet the criteria he described, symptoms must have been present before the age of 30 months. This firmly cemented autism as a developmental disorder. Prior to the publication of Kanner’s article children with similar behaviors were typically diagnosed as having psychosis or a mental impairment (Trevarthan, Aitkin, Papoudi & Robarts, 1998).

6. Why was autism initially thought of as a mental health disorder?

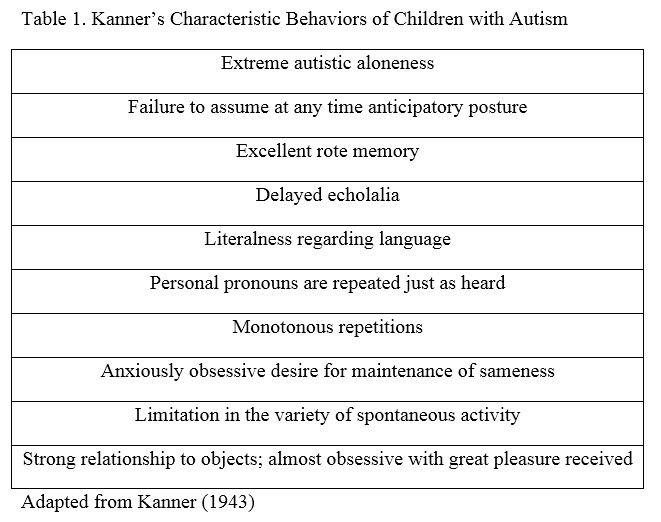

To place these developments into context, there was little information available at that time about the developmental achievements of young children. It wasn’t until the 1950’s that Jean Piaget wrote about key milestones of cognitive development occurring in early childhood (Piaget, 1954). Prior to the publication of Piaget’s work, there was limited understanding of the various developmental domains of early childhood, little research on typical developmental patterns, and even less known about what happened when development went awry. There was scant literature available describing patterns of atypical development, identifying causes, or discussing effective treatments. Piaget’s work spurred those interested in early childhood to begin to think carefully about developmental patterns and what was expected at certain periods of time (Table 1).

7. What are the characteristics of autism as described by Kanner?

Kanner used his observations from children in his practice to delineate the characteristics of autism. These characteristics are listed in Table 1. What remains extremely interesting and relevant about Kanner’s work are the detailed description of the behaviors he observed. Many of these descriptions are consistent with criteria for autism in present day. Note how many of these behaviors refer to language forms or patterns (e.g. echolalia, difficulties with pronoun reversal) which SLPs will use as part of diagnosis and treatment planning.

8. Is Kanner’s criteria still relevant today?

Yes! The key characteristics Kanner described in the 1940’s remain core features of what we now call “autism spectrum disorder (ASD).” Current criteria for ASD involve two key areas – extreme difficulties with social communication and restricted behavioral interests. Much of what Kanner observed in his patients were challenges in language and communication: use of echolalia, problems with syntax and grammar (e.g. reversals of pronouns) and semantic difficulties (e.g. extreme literalness of meanings). While these core characteristics remained constant over time, researchers have differed on two fundamental issues: the cause of ASD and effective treatments.

9. What other conclusions did Kanner draw?

Kanner believed autism was a biological disorder of affective functioning and he wrote extensively about the emotional component of the disorder. Interestingly, a number of treatments related to emotion, specifically affect and social engagement are now popular (Robinson, 2011; Prelock & McCauley, 2012). One conclusion Kanner drew that has not held the test of time was his observation that parents of children with autism were high-achieving in education and profession. Numerous studies have failed to establish a link between educational level or social status and autism (Volkmar, Lord, Bailey, Schultz & Klin, 2004).

10. How did awareness of autism begin to grow?

Autism was not yet well known in the mid-twentieth century, and many individuals with autism were likely given other diagnoses, such as mental retardation, schizophrenia, or psychosis. In his memoir about life with a brother, and later, a son with autism, Charles Hart wrote about the struggles his parents faced raising a young man with unusual and poorly understood behaviors. He writes “There was no way of understanding this strange child. He couldn’t explain anything himself and it appeared that no one had ever seen anyone like him. The family accepted his condition as some unusual form of mental retardation, an affliction no one could understand, except, perhaps, God” (Hart, 1989. p.7). Hart drew a stark contrast between the services available to his brother, born in 1920’s, and his son, born in the 1970’s. After seeing the effectiveness of therapy for his son, Hart was able to understand the struggles his brother experienced so many years earlier. With great poignancy, Hart wonders why it took so many years to find those answers. He explains how Kanner’s writings formed the foundation for later efforts to explore effective treatments. Yet, the lingering question for Hart through the 1970’s and 1980’s was “why” – why did this happen to his brother, and again, to his son?

11. What have been the theories about potential causes?

An unfortunate theory that was popularized in the 1940’s and 1950’s was that autism was caused by distant, emotionally stingy parenting. This hypothesis was attributed to the psychiatrist Bruno Bettelheim and also used by Kanner in later writings. Though this theory was dismissed in the 1960’s, many practitioners persisted in their belief that deficiencies in parenting caused autism. For decades parents were offered treatments to improve their own parenting skills because their parenting practices were believed to be at the root of their child’s disorder (Barron & Barron, 1994; Maurice, 1993). Theories supporting the psychogenic nature of the disorder persisted through the 1960’s and were finally dispelled in the 1970’s.

12. Is it common for individuals to receive different diagnoses?

In an autobiography describing her early life with autism, Temple Grandin lists the numerous diagnoses she was given by doctors, therapists and educators throughout her life (Grandin & Scariano, 1986). Grandin is likely the most famous person in the world with autism. At age six months, her mother noticed that she stiffened when picked up. This was the beginning of a number of observations of unusual behaviors which eventually led to an appointment with a neurologist in 1950 when Grandin was three years of age. Because Grandin did not display the specific characteristics described by Leo Kanner, she was diagnosed with a speech disorder, and later received varied diagnoses throughout her childhood and adolescence, including brain injury and emotional disturbance. When Grandin had difficulties in middle school, her psychiatrist wrote to the head teacher of the school to explain her challenging behaviors. In his letter, he described Grandin’s “very disturbed early childhood” and early diagnosis of brain damage, which was later rejected. He noted that her IQ was tested as very superior (i.e., a full-scale IQ of 137 was measured in 1959 when Grandin was 9 years old) yet she consistently failed to perform up to this level. He described her as a “neurotic child – she has a well-formed personality organization, and the controls to maintain this organization except in cases of severe stress” (Grandin & Scariano, 1986, p.62). Grandin’s experience is one that many families have experienced.

13. Would Temple Grandin qualify for an autism diagnosis under the DSM 5?

If diagnosed today, Grandin would likely meet current diagnostic criteria for ASD, as the characteristics are much broader and include behaviors seen in high-functioning individuals. The challenges Grandin experiences in situations of high stress would likely be diagnosed as anxiety. Along with depression, anxiety is often present in adolescents and adults with ASD and is considered to be an associated feature that supports diagnosis (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

14. What caused the shift toward a developmental perspective?

With the dawn of the 1970’s greater awareness about autism led to an increase in diagnosis. Research efforts focused on studies of causality and verification of core characteristics in order to build consistency in diagnostic practices and provide clear guidelines for physicians. One effort was to differentiate autism from other psychotic disorders. A key contributor to this dialogue was Michael Rutter, a child psychiatrist, who began his study of children with autism in the 1960’s. Rutter (1972) argued that autism was profoundly different from schizophrenia and other psychoses. He emphasized there was no evidence to support a psychogenic origin for autism or mental retardation (now referred to as cognitive impairment) and recommended autism be considered a medical disorder of unknown origin. He proposed simplified core criteria:

- Onset before the age of 30 months;

- Impaired social development (with a number of unique features) and out of keeping with the child’s intellectual level;

- Delayed and deviant language development (also with key features);

- Insistence on sameness, demonstrated by stereotyped play patterns, abnormal preoccupations, or resistance to change.

Rutter recommended clinicians collect data on IQ level and neurological and medical status as part of the diagnostic process (1978). Rutter’s contributions were significant to the field; his list of core features enabled improved consistency in diagnostic practice.

15. Why is consistent use of criteria so important?

The issue of consistency is not a unique quandary for autism practitioners. This practice is crucial when a biological marker for a disease is not available. Advances in genetics have helped in differential diagnosis of some disorders that share features of autism. Fragile X disorder and Rett syndrome, which share characteristics of autism, can now be confirmed through genetic testing. The genetic mutation for Rett syndrome, which is on the X chromosome and primarily affects females, was discovered in 1999 (Amir & Zoghbi, 2000). Prior to the identification of the cause of Rett syndrome, many girls who were later diagnosed with Rett syndrome were initially labeled as having autism (Bartolotta et al., 2011). Similarly, young males with difficulties in social, cognitive and language development may receive a diagnosis of autism before testing positive for Fragile X syndrome. Though it is rare for autism and Rett syndrome to co-occur, autism occurs in approximately 20% of males with Fragile X (Hatton et al., 2006).

16. When did we begin to view autism as a pervasive developmental disorder?

In 1980 autism was included as a disorder under the pervasive developmental disorders category in the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM III) and Rutter’s criteria were used as features on which to base a diagnosis (American Psychiatric Association, 1980). These criteria remained intact until the next revision of the DSM was published in 1994. In the meantime, awareness of the needs of persons with autism grew as educational programs were added in the wake of federal legislation which mandated that all children were entitled to a free, appropriate, and individualized education. The passage of Public Law 94-142 in 1975, known as the Education of All Handicapped Children Act, was a watershed moment for the education of children with disabilities in the United States. This legislation enabled children with autism to be included in public education programs. This federal law is now known as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) and continues to provide guidelines to states on how individuals with disabilities, including autism, should be educated (U.S Department of Education, 2004).

17. How did PL94-142 affect the education of children with autism?

As a result of PL 94-142, the options for educational and therapeutic alternatives for families grew tremendously. Children with autism could now be educated in schools and families provided with information and support services. A number of private day and residential schools specifically dedicated to persons with autism opened. Initially, a large majority followed a behavioral approach to intervention. Many adopted the principles of behavioral treatment adopted from the work of Ivar Lovaas, who wrote of the great progress made by a number of children with autism, even recovery from the disorder, as a result of his intensive discrete trial training program (1987).

18. Did these changes affect intervention practices?

In the 1980’s and 1990’s there were many advances in the understanding of the various domains of child development. This burgeoning literature influenced interventionists, who began to develop more naturalistic approaches built on the precepts of naturalistic learning environments (Greenspan & Weider, 1997; Prizant and Wetherby, 1998). As the variety of treatments grew over time, the range of options available for families grew, though deciding about which type of therapy was best wasn’t, and still isn’t, clear. The range of choices is quite broad, and we lack evidence on which type of treatment is best for particular individuals with ASD.

19. What caused the shift towards viewing autism as a spectrum disorder?

The 1990’s were a time for significant change in the autism world. In response to efforts to include persons with milder symptoms of the disorder, and in recognition of other disorders with similar characteristics, the DSM IV presented the concept of a spectrum of distinct, yet related disorders under the umbrella of autism (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). The spectrum, which remained in place until the publication of DSM 5 in 2013, included five distinct yet related disorders: Autism, Rett syndrome (RTT), Childhood Disintegrative Disorder (CDD), Asperger’s Disorder, and Pervasive Developmental Disorder – Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS). RTT and CDD were included because their core features are similar to autism.

20. What’s next?

In Part II of this series, we’ll discuss the changing paradigm of autism, from a single disorder to a spectrum disorder. We’ll look carefully at each label within the spectrum as described in 1994 and again in 2000 - (Rett syndrome, Asperger’s Disorder, PDD-NOS, Autism and Childhood Disintegrative Disorder – (American Psychiatric Association, 1994; American Psychiatric Association, 2000) and then discuss some of the developments that led to the new criteria in DSM 5. These new criteria sparked a lot of discussion, and we’ll cover some of the major issues, such as the impact on the Asperger’s community. We’ll end with a discussion of the evolving role of the SLP and a look forward at what might be next.