From the Desk of Ann Kummer

Culture is a concept that encompasses the shared values, beliefs, customs, and practices of a group of people, shaping their worldview and interactions. Culturally responsive practices in education involve recognizing and valuing these diverse cultural backgrounds to create an inclusive and effective learning environment for all students of call cultures. By integrating students’ cultural references into the curriculum, educators can make learning more relevant, engaging, and effective.

Here is some information about Dr. Yvette, the author of this article on Engaging in Culturally Responsive Practices. Yvette D. Hyter, PhD, CCC-SLP, ASHA Fellow, is Professor Emerita of Speech, Language, and Hearing Sciences at Western Michigan University in Kalamazoo. Her work focuses on the influences of culture on communication development with emphasis in social pragmatic communication in children who speak African American English and children with histories of maltreatment. She developed a social pragmatic communication assessment battery for young children. Dr. Hyter has expertise in culturally responsive and globally sustainable practices; co-teaches study-abroad courses about causes and consequences of globalization on systems, policies, and practices; has published articles underscoring the need for conceptual frameworks guiding practice in culturally responsive and globally sustainable ways; and served in national and international leadership positions regarding global practice, equity, diversity, and inclusion. She is the co-author of the book entitled Culturally Responsive Practices: In Speech, Language, and Hearing Sciences, 2nd edition, Plural Publishing, Inc., 2018. Currently, Dr. Hyter is the owner of Language and Literacy Practices, LLC. through which she provides culturally and linguistically responsive, and trauma informed assessments, interventions and educational consultations in the U. S. and around the world.

In this 20Q article, Dr. Yvette Hyter explains how culturally responsive practices should be considered and implemented in our treatment practices. This course defines culturally responsive practices and presents a conceptual framework to guide these practices.

Now…read on, learn, and enjoy!

Ann W. Kummer, PhD, CCC-SLP, FASHA, 2017 ASHA Honors

Contributing Editor

Browse the complete collection of 20Q with Ann Kummer CEU articles at www.speechpathology.com/20Q

20Q: Engaging in Culturally Responsive Practices

Learning Outcomes

After this course, readers will be able to:

- Define culture and culturally responsive practices (CRP).

- Differentiate culturally responsive practices from diversity.

- Describe a pathway to CRP.

- Explain some conceptual frameworks that can be used to guide our culturally responsive practice, and

- Explain the importance of interrogating and employing concepts that better guide our culturally responsive practices.

1. What is the definition of culture?

Culture is comprised of the underlying assumptions and world views of groups of people who have shared problem-solving strategies, beliefs, artifacts, and forms of communication that are passed from one generation to another. These underlying assumptions and worldviews are learned over time, drive behaviors (e.g., visible practices such as how someone dresses or which holidays are celebrated) and become one’s culture (Hyter & Salas-Provance, 2023). Hammond (2015) states that culture is based on mental models and determines how we learn new information. In this way, culture is part of how the “brain makes sense of the world and helps us function in our environment.” (p. 23). This is one of the reasons why it is so important to engage in practice in culturally responsive ways. Indigenous American scholar Coulthard (2014) also shares that culture is the “interconnected social totality distinct mode of life encompassing the economic, political, spiritual, and social.” (p. 65) Culture, then, is the underlying beliefs, values, and worldviews compelled by a history of problem-solving strategies, drives daily practices that are transmitted from one generation to the next, programs our brain to interpret the world around us, and encompasses every aspect (i.e., the totality) of life.

2. What are Culturally Responsive Practices?

Culturally responsive practices take the cultural experiences, history, influences, and perspectives of others into consideration in all aspects of education and the provision of support (Gay, 2018; Hyter & Salas-Provance, 2023). These are dynamic practices that continue to transform depending on one’s context and require the user to engage in continuous critical self-reflection.

3. Are there other similar concepts?

Yes. Other similar concepts are culturally relevant and culturally sustaining pedagogies and practices. Culturally relevant pedagogy was coined by Gloria Ladson Billings (1995), who stressed the importance of educators drawing on the cultural and linguistic strengths of the children they are teaching. Culturally sustaining practice or education (Paris & Aim, 2017) means fostering linguistic and cultural pluralism to transform educational practices. They state that “culturally sustaining pedagogy exists wherever education sustains the lifeways of communities who have been and continue to be damaged and erased through schooling.” (p. 1)

4. Aren’t culturally responsive practices just another name for diversity work?

Often, diversity and culturally responsive practices are conflated; however, they are very different. Diversity simply focuses on having the representation of various ethnicities, cultures, genders, socioeconomic backgrounds, languages, religions, etc. within an organization. To illustrate, consider a bag of fruit. If there are only apples in the bag, then there is no diversity. If, on the other hand, there is a mix of apples and oranges, there is diversity – a diversity of fruit. The container of this diverse fruit, the bag, remains unchanged. The bag is the structure, and if the structure holding the diverse fruit remains the same, so will everything else. Changing what’s inside the same old structure does little to advance equity and justice. American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) is comprised of diverse ethnic groups (ASHA, 2022). Specifically, according to the 2022 member counts, 0.3% are Indigenous Americans, 3.6% are Black, 3.3 are Asian and Pacific Islanders, 1.5% are multiracial, and 91.1% are White. Although it is a majority White discipline, there is ethnic diversity. The bag (i.e., the discipline, the policies, the practices) remains the same, which may or may not serve all the different cultures and ethnicities represented within that structure – ASHA. Cultural responsiveness focuses on tearing away the bag – the structure – to build one without barriers and one that is more equitable, more inclusive, and more just (Hyter, 2024).

5. What is one of the first skills to acquire that will help you engage in culturally responsive practices?

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, a Nigerian writer, has a Ted Talk titled, The Danger of a Single Story. One of the most important skills that we need to develop is what Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie talks about . . . eliminating all the single stories that we have about others who are not ourselves. Eliminating “single stories” is part of employing cultural humility.

6. What are some tools that we need to have in our culturally responsive toolbox?

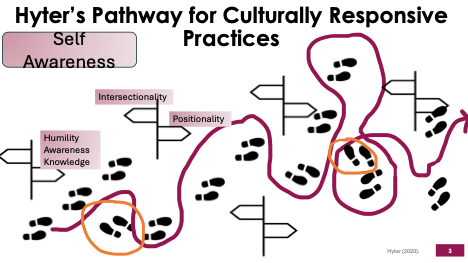

We are all on a continuing, hopefully, moving toward more and more cultural responsiveness in our practices. This continuum or pathway is not linear but progress, and sometimes, we falter on our journey, make some mistakes, and go backward. Nevertheless, it is my hope that we continue to press on to learn from our mistakes, engage in continuous critical self-reflection, and refine our abilities to be culturally responsive clinicians. We need to develop (a) abilities in self-reflection (see Figure 1), (b) new knowledge (see Figure 2), and (c) skills,

7. What self-awareness abilities should we have to engage in effective culturally responsive practices?

Figure 1 shows that we are all on a pathway toward culturally responsive practices and that some rudimentary self-awareness is needed in our culturally responsive toolbox—cultural humility, cultural awareness, cultural knowledge, and understanding our own and others’ intersectionality and positionality.

Figure 1. Hyter’s Pathway for Culturally Responsive Practices: Self-Awareness

8. What is cultural humility, awareness, and knowledge?

Cultural humility is the ability to suspend our own cultural assumptions and worldviews, be willing to learn from others and value the cultural beliefs, values, and assumptions of others (Tervalon & Murray-Garcia, 1998; Haynes-Mendez & Engelsmeier, 2020; Hyter & Salas-Provance, 2023). Cultural awareness is being aware of one's own cultural values and beliefs, whereas cultural knowledge is learning about and understanding the cultural values and beliefs of others (Hyter & Salas-Provance, 2023). In addition to cultural humility, awareness, and knowledge, two other self-awareness needs are an understanding of your own and others’ intersectionality and your own positioning.

9. What are intersectionality and positionality and their purposes?

Intersectionality is the concept coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw (1989) that explains that it is interconnection (intersection) among our identities. The primary premise of intersectionality, a conceptual framework, is that all our social positions (such as ability, age, education, gender, language, nationality, race, language, and sexuality) affect us all at the same time – which can result in both privileges and marginalization (Lin, 2024). None of us have only one identity. For example, I am not only a woman nor only Black, but both of those identities intersect in my world. I identify as a black cis-gendered, right-handed woman who practices Christianity and a critical theorist whose work focuses on transdisciplinarity and qualitative methods. Some of these identities (i.e., cis-gendered, right-handed, practicing Christianity) are identities that afford me privileges. The others (Black woman, critical theorist, transdisciplinarian, qualitative methods) are identities that have caused marginalization depending on the context. Knowing about intersectionality will help us understand the compounded experiences of systemic exclusion and inclusion, knowledge that will support our utilization of culturally responsive practices.

Positionality is acknowledging the social, political, economic, cultural, and ecological contexts that created our identities and their unequal power systems (Boveda & Annamma, 2023). Ultimately, positionality is about how we negotiate support and engage with those who are typically or traditionally marginalized in systems, policies, and practices (Boveda & Annamma, 2023).

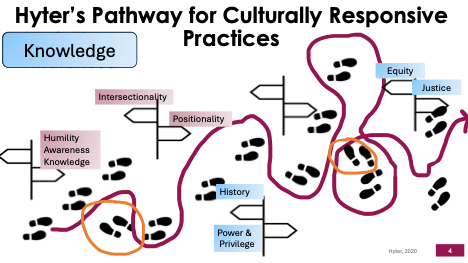

10. What knowledge should we have to engage in effective culturally responsive practices?

In addition to Self-Awareness, to become and continue to grow as culturally responsive clinicians, we need knowledge of cultural histories, power and privilege, equity and equity-mindedness, and justice. Figure 2 shows the knowledge required for engaging in culturally responsive practices. When we study a group’s cultural history, we learn about its everyday experiences, life events, beliefs, values, and worldviews. This includes studying and understanding one's own cultural history. Examining and understanding one's own cultural history is one of the early steps in becoming a culturally responsive clinician.

11. What are the differences between power and privilege?

Power is the ability to make decisions without reciprocity; that is, the decisions disadvantage others’ lives but not necessarily your own (Hyter, 2008). These decisions are made in the interest of your own group but not others (Hyter et al., 2017). Privilege is an unearned advantage based on perceived or real identities (e.g., race or gender). These unearned advantages are often at the expense of disadvantaged others who are disadvantaged (Webster & Handrikman, 2020). Limited knowledge about how power and privileges can operate within a clinical practice could result in being insensitive to the needs of those with whom we are collaborating in their care.

Figure 2. Hyter’s Pathway for Culturally Responsive Practices: Knowledge.

12. What is equity and justice?

Equity occurs when everyone, regardless of race, culture, socioeconomic background, gender, or nationality, has the resources and opportunities they need. Approaching clinical practices with an equity mindset – attending to patterns of inequity - would ensure that all the people and families clinicians support in their care would have what they need to be successful (Yu et al., 2022, p. 2). Social justice means eliminating all forms of discrimination, which can be done using two types of remedies – affirmative and transformative remedies (Fraser, 2009; Heidelberg, 2019). Affirmative remedies are designed to change outcomes without changing the structure. Think again about the paper bag example mentioned earlier. Affirmative remedies are likened to simply influencing a diverse array of fruit in the same bag or increasing the number of people from a range of identities in an organization. This is not a lasting change. Transformative remedies, on the other hand, address the causes of the inequities and become institutionalized within an organization. Incorporating social justice into your culturally responsive practice could utilize both affirmative and transformative remedies.

13. You mentioned skills that should be learned and utilized. What are those skills?

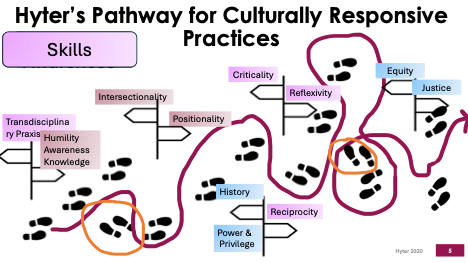

Figure 3 shows the critical skills required for culturally responsive practices. These skills are transdisciplinary praxis, criticality, reflexivity, and reciprocity. Transdisciplinary praxis means to participate in collective dialogues and reflections about clinical practice (Hyter, 2008, 2014). Taking time to participate in these dialogues will help us be in a state of continual critical reflection about our practice. We typically engage in self-reflection, but critical self-reflection requires criticality or the state of being critical. Critical self-reflection occurs when we question our own values, beliefs, and assumptions and how we might uphold traditional unequal power relationships in our practice. This critical self-reflection will also help us rectify unequal power relationships between us, clinicians, and those with whom we partner in their care.

Figure 3. Hyter’s Pathway for Culturally Responsive Practices: Skills

14. What is criticality, reflexivity, and reciprocity?

Hyter and Salas-Provance (2023) define criticality or the state of being critical as the ability to examine unequal power relations created by the historical, sociocultural, political, economic, and ecological social structures that maintain those unequal power relations. Abrahams et al. (2019) add that the critical helps us “redress marginalization and redistribute power and resources.” (p. 10). Criticality helps us engage in critical self-reflection as we recognize our own power and positioning that can impact (positively or negatively) our interactions with our clinical partners. Reflexivity is like looking at ourselves in a mirror; however, critical reflexivity is like looking at ourselves through the lens of power – where we problematize our own thinking. This critical self-reflexivity is essential for understanding what might be preventing us from understanding others’ points of view. Finally, reciprocity is being able to engage in bidirectional interactions with individuals and families that we support, allowing a balanced/equitable exchange of ideas.

15. What is a conceptual framework and why we should use one?

A conceptual framework is like a roadmap that we can use to guide our practices. We utilize conceptual frameworks all the time to guide our intervention with a particular person and/or case. It is important to use conceptual frameworks also to guide our culturally responsive practice; however, using a language learning framework will not aid in employing culturally responsive practices.

16. What are the conceptual frameworks one might use to guide culturally responsive practices?

There are at least three frameworks that I suggest starting with to guide your culturally responsive practices. These are social determinants of health, a social-ecological framework, and a critical theory approach.

17. What are the social determinants of health, and how do they affect outcomes?

Social Determinants of Health are conditions present in our social environments that can impact health outcomes. These conditions or factors include socioeconomic factors, physical environment, health behaviors, and access to health care. Of these factors, 40% of our health outcomes are influenced by socioeconomic factors, which include education, job status, family and social support, income, and community safety (Whitman et al., 2022). Most (80%) of what determines one’s health outcomes is based on what happens beyond the hospital (Whitman et al., 2022).

18. Can you explain what is meant by the social-ecological framework?

The Social-Ecological Framework, based on Bronfenbrenner's work (1979), focuses on the interconnection among the different components of one’s life—individual, interpersonal, community, and policy. At the individual level, one's biological and personal history comes into play. In our clinical practice, we would collect this information through an ethnographic interview (at best) and/or a standard history form. The interpersonal level (microsystem) focuses on the person in a relationship with their family and peers. The community level of this model (exosystem) includes the community organizations and institutions to which the person might belong or utilize, such as schools, work, neighborhood, and extended family. The last level, policy (macrosystem), focuses on how local, state, national, and international policy and law may influence our practice and support of an individual or family. Utilizing either social determinants of health or a socioecological framework to guide our culturally responsive practices will result in consideration of the macro-level structures (cultural, political, economic, and ecological) that influence daily life and one’s ability to seek and utilize support.

19. What is the critical theory approach, and how does it relate to outcomes?

A critical theory approach helps us focus on identifying and eliminating or dismantling the unequal power relations created by social structures, that is, by historical, sociocultural, political, economic, and ecological structures (Hyter & Salas-Provance, 2023). As a result, our practice will include addressing marginalization and redistributing power and resources (Abrahams et al., 2019, p. 10). Some premises associated with a critical framework include (1) a historical perspective is essential for explaining the present, (2) analysis of any problem must be intersectional and cross-disciplinary in order to completely understand it, (3) knowledge cannot be separate from action (praxis is necessary) and is not/cannot be objective, and (4) dialectical thinking must be used to think in a new way (Hyter, 2008, 2014, 2024; Hyter & Salas-Provance, 2023; Pillay, 2003; Stockman, 2007). Using this framework to guide our culturally responsive practices results in an acknowledgment of our own cultural histories and incorporating our clinical partner’s cultural history into our practice; working across disciplines and engaging in praxis with any case; valuing others’ cultural world views, beliefs, and values as worthy as our own; and thinking outside the box, against the status quo to address clinical concerns in a new way.

20. In your writing, you’ve stated that it is important to critically review and change concepts to engage in culturally responsive practices. Can you explain why this regular critical review is important?

It is important for us to interrogate the concepts we use because concepts are necessary components of thinking, learning, and theory development and use (Hyter, 2021). Concepts connect our thoughts and behaviors. Every meaning we have for some item or phenomenon determines how we behave toward those items or phenomena. So, if we use the concept of “client,” we behave in ways that limit us to providing a service to another person. Whereas, if we say “clinical partners,” it paves the way for creating partnerships with the individuals and families that we support.

21. What are some concepts that you have examined, and what do you suggest as replacements?

Table 1 provides some concepts that I have examined and decided not to use anymore. I’ve also included the rationale for their elimination and a suggested replacement.

Interrogated Concept | Rational for Elimination | Suggested Replacement |

Client/Patient | Gives the impression that someone is passive and being “served” by another rather than a person who is engaged in partnership with a clinician regarding their own care. | Clinical Partner |

Cultural Competence | Interpreted as a static or fixed ability rather than dynamic, fluid and constantly changing based on the context and people who are within that context | Cultural Responsiveness or Culturally Responsive |

Disorder(s) | Disorder is from a medical model – the problems is within the person and is something that needs to be corrected or eliminated. It focuses on the problem. I am trying to live into a social model of disability, where problem is how society crates barriers that restrict disabled peoples’ lives. | Disability |

Minority/Minorities | Surrogate for less power and/or powerless | Global Majority or name of ethnic group |

Poverty | Puts the blame on the victim of impoverishment for their own condition/status as if there are no external forces at play | Impoverishment |

Standard American English or Standard English | Based on the standard language ideology (Lippi-Green, 2012) an “abstracted, idealized, homogenous spoken language which is imposed and maintained by dominant … institutions. ..” (p. 67) | White American English or White Mainstream English (Alim & Smitherman, 2012; Baker Bell, 2020; Paris, 2009) |

Table 1. Hyter’s Interrogated Concepts, Rational for Elimination, and Suggested Replacements

References

Abrahams, et al. (2019). Inequity and the professionalization of speech-language pathology. Professions & Professionalism, 9(3), e3285. https://doi.org/10.7677/pp.3285

Alim, H. S., & Smitherman, G. (2012). Articulate while Black: Barack Obama, language, and race in the U.S. Oxford University Press.

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2022). Member counts. Retrieved from https://www.asha.org/siteassets/surveys/2022-member-affiliate-profile.pdf

Baker-Bell, A. (2020). Linguistic justice: Black language, literacy, identity, and pedagogy. Routledge.

Boveda, M., & Annamma, S. A. (2023). Beyond making a statement: An intersectional framing of the power and possibilities of positioning. Educational Researcher, 52(5), 306–314. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X231167149

Coulthard, G. (2014). Red skin, white masks: Rejecting the colonial politics of recognition. University of Minnesota Press.

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1(8), 139–167.

Fraser, N. (2009). Scales of justice: Reimagining political space in a globalizing world. Columbia University Press.

Gay, G. (2018). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice (3rd ed.). Teachers College Press.

Hammond, Z. (2015). Culturally responsive teaching & the brain: Promoting authentic engagement and rigor among culturally and linguistically diverse students. Corwin, a SAGE Company.

Haynes-Mendez, K., & Engelsmeier, J. (2020). Cultivating cultural humility in education. Childhood Education, 96(3), 22–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/00094056.2020.1766656

Heidelberg, B. M. (2019). Evaluating equity: Assessing diversity efforts through a social justice lens. Cultural Trends, 28(5), 391–403. https://doi.org/10.1080/09548963.2019.1680002

Hyter, Y. D. (2024, February 16). Culturally responsive practices in speech-language-hearing sciences. A six-hour workshop presented for the Cleveland Metropolitan School District, Cleveland, Ohio.

Hyter, Y. D. (2021). Power of words: A preliminary critical analysis of concepts used in speech, language, and hearing sciences. In R. Horton (Ed.), Critical perspectives on social justice in speech-language pathology (pp. 60–82). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-7134-7.ch004

Hyter, Y. D. (2020). Pathways for culturally responsive practices: Self-awareness, knowledge, and skills. Unpublished graphic. Language & Literacy Practices, LLC.

Hyter, Y. D. (2014). A conceptual framework for responsive global engagement in communication sciences and disorders. Topics in Language Disorders, 34(2), 103–120.

Hyter, Y. D. (2008). Considering conceptual frameworks in communication sciences and disorders. ASHA Leader, 13, 30–31.

Hyter, Y. D., Roman, T. R., Staley, B., & McPherson, B. (2017). Competencies for effective global engagement: A proposal for communication sciences and disorders. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 2(Part 1), 9–20. https://doi.org/10.1044/persp2.SIG17.9

Hyter, Y. D., & Salas-Provance, M. B. (2023). Culturally responsive practices in speech-language & hearing sciences (2nd ed.). Plural Publishing.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). The dreamkeepers: Successful teachers of African American children. Jossey-Bass.

Lin, S. (2024). Immigrant and racialized populations’ cumulative exposure to discrimination and associations with long-term conditions during COVID-19: A nationwide large-scale study in Canada. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-024-02074-1

Lippi-Green, R. (2012). English with an accent: Language, ideology, and discrimination in the United States. Routledge.

Paris, D. (2009). They’re in my culture, they speak the same way: African American language in multiethnic high schools. Harvard Educational Review, 79(3), 428–448.

Paris, D., & Alim, S. (n.d.). Culturally sustaining pedagogies: Teaching and learning for justice in a changing world. Teachers College Press.

Stockman, I. (2007). Social-political influences on research practices: Examining language acquisition by African American children. In R. Bayley & C. Lucas (Eds.), Sociolinguistic variation: Theories, methods, and applications (pp. 297–317). Cambridge University Press.

Tervalon, M., & Garcia-Murray, J. (1998). Cultural humility versus cultural competence: A critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 9(2), 117–125.

Webster, N. A., & Handrikman, K. (2020). Exploring the role of privilege in migrant women’s self-employment. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258720969139

Whitman, A., De Lew, N., Chappel, A., Aysola, V., Zuckerman, R., & Sommers, B. (2022). Addressing social determinants of health: Examples of successful evidence-based strategies and current federal efforts. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services: Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. Retrieved from https://www.aspe.hhs.gov

Yu, B., Nair, V. K. K., Brea, M. R., Soto-Boykin, X., Privette, C., Sun, L., Khamis, R., Chiou, H. S., Fabiano-Smith, L., Epstein, L., & Hyter, Y. D. (2022). Gaps in framing and naming: Commentary to “A viewpoint on accent services.” American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 1(6). https://doi.org/10.1044/2022_AJSLP-22-00060

Citation

Hyter, Y. D. (2025). 20Q: engaging in culturally responsive practices. SpeechPathology.com, Article 20722. Retrieved from www.speechpathology.com