From the Desk of Ann Kummer

Speech-language pathologists (SLPs) are experts in normal language development, language disorders, and language remediation. This expertise in all aspects of language is particularly valuable in the school setting! This is because receptive and expressive language skills are prerequisites for learning to read and write. In fact, language skills are necessary for all learning that takes place in school. Therefore, Dr. Shari Robertson argues that SLPs’ knowledge of language is a superpower! I tend to agree.

In this article, Dr. Robertson describes the “Language-Literacy Hierarchy” and how it applies to learning to read, write, and learn content in school. She goes on to discuss how SLPs can effectively use their expertise in language to support academic success. Examples of therapeutic activities, templates, and lesson plans for small group and classroom-based intervention will be shared.

Here is a little information about Dr. Robertson. Shari Robertson, PhD, CCC-SLP, is an ASHA Fellow and Board-Certified Specialist in Child Language (BCS-CL). She is a professor emerita and a retired Associate Provost of Indiana University of Pennsylvania. Dr. Robertson is currently the CEO of Dynamic Resources. Prior to moving into academia, Dr. Robertson spent 20 years in the public schools as a broad-range SLP and Administrator, and she continues to be a strong advocate and innovator in areas related to schools-based intervention. Dr. Robertson has received the Editor’s Award for Language from the Journal of Speech-Language-Hearing Research and the Annie Glenn National Award for Leadership in Language and Literacy. In addition, she served as the 2019 President of the American Speech-Language and Hearing Association (ASHA). Dr. Robertson is committed to helping her colleagues thrive in their personal and professional pursuits and continues to spread the message of the importance of making effective communication a human right, accessible, and achievable for all.

This course will encourage SLPs to embrace their language expertise, share it with others, and apply it to therapy guided by five evidence-supported principles.

Now…read on, learn, and enjoy!

Ann W. Kummer, PhD, CCC-SLP, FASHA, 2017 ASHA Honors

Contributing Editor

Browse the complete collection of 20Q with Ann Kummer CEU articles at www.speechpathology.com/20Q

20Q: Efficient and Effective Language Intervention in the Schools -

Embrace Your Superpower

Learning Outcomes

After this course, readers will be able to:

- Explain the value of the comprehensive expertise in language that SLPs bring to the school setting.

- Describe five principles that facilitate efficient, effective language intervention in the schools.

- Describe how to implement evidence-supported language intervention strategies that are educationally relevant and immediately useful.

1. The title of this article is intriguing. Why do you consider language to be a school-based SLP’s superpower?

Plain and simple, speech-language pathologists (SLPs) are the language experts in the schools. They hold in-depth knowledge of normal and disordered oral language development and its relationship to literacy and learning that is unique among school personnel. However, in many cases, this comprehensive language knowledge base is so engrained in our collective “SLP DNA” (my term) that school-based SLPs do not fully comprehend the incredible value of their expertise to both individual students and to the school as a whole. It truly is a superpower!

2. Can you expand on that a little bit? Why is oral language so vital to academic success?

In study after study, researchers have found that early deficits in oral language are highly correlated with constraints in reading, writing, and academic achievement (e.g., Nation & Snowling, 2004; Kahmi & Catts, 2012; Roth et al., 2002; Scarborough, 2001). For example, Catts et al. (2002) noted that among children with language delay in kindergarten, 50% were eventually identified with a reading disability in first or second grade. A longitudinal study by Stothard et al. (1998) found that children with weak language skills at 5½ were found to have poor reading comprehension at 8½ and 15½.

Further, Stanovich (1986) found that children with small vocabularies in the early grades learned words slower than their peers, setting in motion a spiral of negative effects, such as frustration, antipathy, and failure, that is difficult to break. For instance, rather than learning 3000 new root words a year (the average for typically developing children), students with language deficits or delays may only learn 1200, causing them to fall further and further behind. This suggests that they will graduate—if they graduate—with a vocabulary smaller by nearly 22,000 words than their typically developing peers. In other words, deficits in oral language are comprehensive, cumulative, and durable.

3. Does it work the other way as well? Are children with well-developed language skills more apt to do better academically?

Absolutely. Research has proven again and again that children who have a strong oral language base are likely to learn to read, write, and find academic success more easily than students whose oral language skills are even slightly constrained (e.g., Catts et al., 2002).

This is not really new information for the vast majority of SLPs who intuitively understand the importance of language to literacy and learning. But, given the critical role that language plays in classroom success, SLPs really need to be able to explain it to others in a way that non-SLPs can understand.

4. Okay, so how can we share this critical information with others?

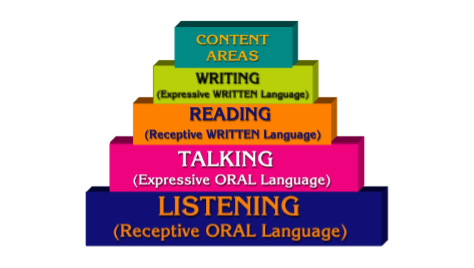

Figure 1. Language-Literacy Hierarchy.

When I was a supervisor in the public schools in West Bend, Wisconsin, there was a principal who really did not understand our role. Virtually every time I entered that particular building, he would stop me and demand, “Tell me again what speech teachers do?” The cringe factor of the “speech teacher” title aside, I realized I needed to come up with a concrete way to help him understand and appreciate the value that SLPs knowledge of language brought to the academic setting. The graphic provided here was the result. Since then, I have very successfully used the Language-Literacy Hierarchy to demonstrate the critical role of oral language in reading, writing, and success in the content areas to parents, teachers, doctors, reading specialists, psychologists, and, yes, principals.

5. How does the Language-Literacy Hierarchy Work?

There are two parts to using the Language-Literacy Hierarchy. Part 1 is a description of the tiers, along with some simple (but powerful) examples. Here is a brief summary of the narrative I typically use:

Receptive oral language, the base of the hierarchy, is the largest area of language development and is the first area to develop (most people know that children understand language long before they produce it – although I have been surprised by people who should know this, but do not). The second tier, expressive oral language, is a subset of receptive oral language in that speakers do not use words or grammatical forms (or other aspects of language) in their conversations that are not a part of their receptive language base. For example, a child will not name a giraffe when visiting the zoo if they do not have the concept of giraffe in their receptive oral vocabulary. Older children will not use a passive form while speaking (e.g., The cat was chased by the dog.) if they do not understand the passive voice.

The next two tiers of the hierarchy, receptive written language (reading) and expressive written language (writing), are dependent upon, and subsets of, the oral language tiers. To drive this point home, I often ask someone in my audience to read aloud a word that is easy to decode but not likely in their oral language vocabulary. (A favorite is “gaskin,” but “spasmophonia” works well with non-SLP audiences!) Once decoded, I ask them to tell me what the word means. When they cannot, I point out the obvious. Just because you can decode a word does not mean you know its meaning–it must also be a part of your oral language vocabulary (Gough & Tumner, 1986). So, children who struggle with reading comprehension may decode words adequately, but constraints on their oral language are the underlying cause of their reading problems.

At the top of the Language-Literacy Hierarchy are the academic content areas, such as social studies, science, and math. Note that this is the smallest of the tiers, and success in these subjects is based on the strength of the oral (speaking and listening) and written (reading and writing) language tiers that support it.

6. That all makes sense. So, what is the second part?

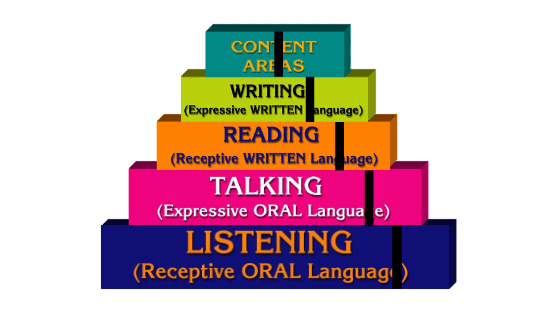

Now comes the most powerful part of this demonstration. Using a marker, slightly decrease the size of the receptive oral base tier. Then, reduce each tier proportionally (see Figure 2). It quickly becomes obvious, even to an untrained eye, that even a relatively small reduction in the size of the receptive oral language base has an ever-increasing negative effect on the tiers above. The end result is very substantial deficits in written language and the content areas. (The best response I ever got to this demonstration was from a group of 5th-grade teachers who stood up as a group and exclaimed, “See, it’s not our fault!")

Figure 2. Language-Literacy Hierarchy - Revised.

Clearly, if we want to ensure children reach their full potential academically (not to mention socially and vocational), we need to ensure they have developed a robust oral language foundation. SLPs (unleashing their superpowers) provide sustained, systematic support necessary to accelerate learning or compensate for deficiencies in the language domains. (This is when the principal “got it” and never asked again. In fact, he asked for additional SLP support for his school).

7. Where can I access a full-sized graphic and narrative script for the Language-Literacy Hierarchy?

A reproducible PDF and an expanded script can be downloaded from the Dynamic Resources website (www.dynamic-resources.org) under the Free Resources tab. You can request an animated PowerPoint of the Language-Literacy Hierarchy to use in your own demonstrations there as well.

8. How can SLPs most effectively use their expertise in language to support academic success?

Given the scope and breadth of language across form, content, and use, answering this question may be daunting. Obviously, school-based SLPs do not have the luxury of unlimited resources. At the same time, the services they provide must be educationally relevant and immediately useful. So, in essence, it boils down to delivering services that fuse research and practice in a way that is both efficient (greatest amount of change in the shortest amount of time) and effective (change translates into academic and/or social success).

While entire textbooks can (and have) been written about how to accomplish this, I suggest five evidence-supported principles to guide the development of efficient, effective intervention for children with language/learning challenges.

9. Don’t keep us in suspense! What are these principles?

The principles I use to guide intervention for school-aged students are:

- Address oral and written language simultaneously (e.g., Robertson, 2014).

- Incorporate vocabulary development and comprehension into every therapeutic activity (e.g., National Reading Panel, 2000).

- Teach learning strategies and underlying skills that cut across content areas (e.g., Ehren, 2000).

- Make the implicit characteristics of language explicit (e.g., Wallach et al., 2009).

- Ensure educational relevance by linking therapy to core educational standards (e.g., Power-deFur & Flynn, 2012).

These principles are not meant to be addressed individually. Rather, the most efficient, effective intervention activities include all five principles. For instance, targeting morphological awareness supports both oral and written vocabulary and comprehension (e.g., Gibson & Wolter, 2015), is an underlying skill that cuts across multiple content areas, helps students understand the metalinguistics aspects of language by making the implicit morphological construction of words explicit, and has a heavy presence in the Common Core Communication and/or state-specific educational standards.

10. How can I address both oral and written language in therapy protocols? I am already stretched to the limit. I’m not sure I can find the time or energy to add that to my professional to-do list.

Luckily, you don’t have to work harder to target oral and written language simultaneously. The easiest way to accomplish this is to incorporate appropriate children’s books into your therapy activities (Robertson, 2017). In fact, literature-based intervention has been recommended as a best practice to support oral and written language goals for children with language delays for several decades (e.g., Clendon et al, 2014, McKeown & Beck, 2003, Towson & Gallagher, 2016, Robertson, 2014, 2015). One of my favorite studies (Haynes & Ahrens, 1988) revealed that children’s books contain approximately twice as many infrequently used or rare words as conversations among college graduates! Books also provide exposure to more advanced grammatical forms than spoken language and provide an ideal natural context to learn (and learn about) language in context. I am so passionate about the benefits of incorporating quality children’s literature into therapy that I have been publishing children’s books written for SLPs by SLPs for more than a decade.

11. Can you provide a little more background regarding the second principle of targeting vocabulary and comprehension in every therapy session?

In 2000, the National Reading Panel published the results of a comprehensive analysis of the research literature undertaken to identify student skills and instructional strategies that consistently led to reading success. Five skills were identified as being the most critical in developing strong literacy skills: phonemic awareness, phonics, reading fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension. The latter two, vocabulary and comprehension, are considered the highest-level skills. Not surprisingly, they are both language constructs–and have long been in the superpower repertoire of SLPs who work with children. Consequently, ensuring that these skill areas are incorporated into every language therapy session is key to facilitating positive change in both the oral and written domains. (Note that additional studies have been undertaken since 2000 that add to the information provided by this report, but the importance of these five key areas of instruction has not changed.)

12. Can you expand a little on the principle of focusing on skills over content?

Teachers and other classroom personnel teach curricular content. SLPs help students access the curriculum by teaching skills that cut across content areas. Ehren (2000) argues that it is this therapeutic focus on teaching students how to learn rather than what to learn that sets SLPs apart from other school personnel.

So, rather than having students memorize vocabulary words, SLPs might provide intervention focusing on how different semantic categories of words work in sentences to create meaning. Rather than assigning a paragraph to summarize a specific topic, SLPs might help students learn to formulate more complex sentence structures to facilitate more effective writing regardless of the topic (Kim et al., 2004).

13. It seems like there is an overlap between the third guiding principle, teaching underlying skills rather than content, and the fourth, making the implicit characteristics of language explicit. Can you expand on that?

That is absolutely correct. Helping students improve meta-skills (linguistic, cognitive, pragmatic) is fundamental to effective, efficient intervention. However, the importance of explicitly teaching students with language disorders and delays how language “works” cannot be overstated. Language is unique because it is the only school “subject” that is also the vehicle by which you learn that subject (and all of the other subjects as well). Unfortunately, the same characteristics that contribute to student language learning deficits (e.g., poor auditory processing, short-term memory deficits) make it difficult to figure out how language works– creating a kind of double jeopardy for children with language learning deficits. Consequently, deliberate planning to ensure multiple opportunities to engage in activities that provide explicit instruction and guided practice in these important meta-skills is an important component of treatment for language disorders.

14. How do I ensure that the language skills I target are educationally relevant?

The litmus test for eligibility for speech and language services in the schools is whether the identified areas of weakness have a substantial negative impact on attaining the student’s educational goals. In other words, school-based SLP services exist to support academic success. So, we need to be sure we are targeting skills that support classroom learning and grade-level expectations.

Fortunately, regardless of the state in which you practice, you can easily access a consistent framework for what students should know and be able to do at the end of each grade. The Common Core State Standards (CCSS), which have been adopted by most states, define the knowledge and skills students are expected to develop during their K-12 education to ensure success after graduation (National Governors Association Center for Best Practices, 2010). Alternately, some states have chosen to create their own set of standards, which provide a similar set of expectations for each grade. Consistently linking assessment and intervention to Common Core or state-specific standards ensures that therapy goals are matched with the communication needs, grade-level curriculum expectations, and specific demands of the classroom (Power-deFur & Flynn, 2012, Ehren et al., 2012).

Even though school-based SLPs are superheroes, it can be time-consuming (and a little daunting) to sort through all of the standards for each grade level to determine appropriate targets for your students. Consequently, it can be helpful to use a resource such as the Skills-Based Assessment of Core Communication Skills (Schultz, 2016; 2017) to identify relevant knowledge and skills and monitor progress across grade levels.

15. Can you give some examples of therapy activities that include all of these principles?

Of course! That is my favorite part of speaking or writing about intervention for language disorders. Here are some “start with a book” ideas that not only incorporate all of the principles discussed above but are also student-tested and approved.

Note that the information provided here for each activity is necessarily brief; however, a link to more complete information for this (and other) activities is provided at the end of this article.

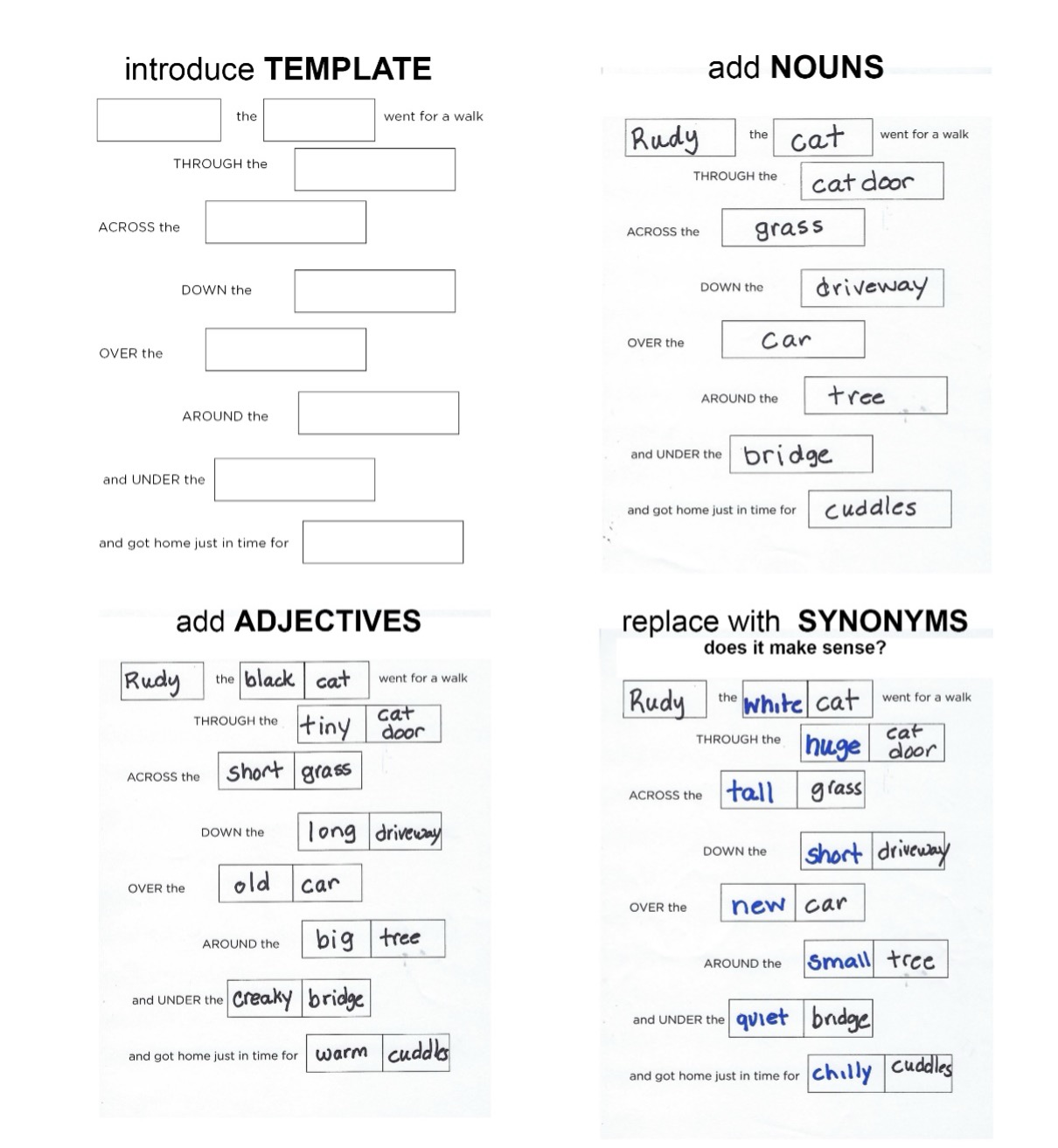

BOOK: Rosie’s Walk by Pat Hutchins (Simon and Schuster)

DESCRIPTION

This book has a very simple structure that lends itself beautifully to the explicit teaching of how words work together to build sentences (metalinguistics). IEP and CCSS targets include semantic categorization/vocabulary development (synonyms, antonyms, adjectives, adverbs), oral and written language comprehension, narrative development, speaking and listening, using illustrations to demonstrate meaning, sentence expansion, and an introduction to a graphic organizer in the primary grades. This is not an all-inclusive list as, with a little imagination, the applications for this activity are unlimited.

METHOD

Read the story: (Rosie the Hen went for a walk across the yard, around the pool, over a haystack, past the mill, through the fence, under the beehive, and got home just in time for dinner.) Using a variety of templates (see examples below), students can create their own versions of the story by adding their choice of nouns, verbs, synonyms, antonyms, adjectives, and other language constructs. (This is a fantastic way to learn how sentences are constructed). Students read the various versions of their story to others, add illustrations, etc.

Figure 3. Rosie's Walk Template.

16. That was a good start. Can you share another idea?

Of course! This book is one of my go-tos for getting kids actively (and I do mean actively) involved in a story.

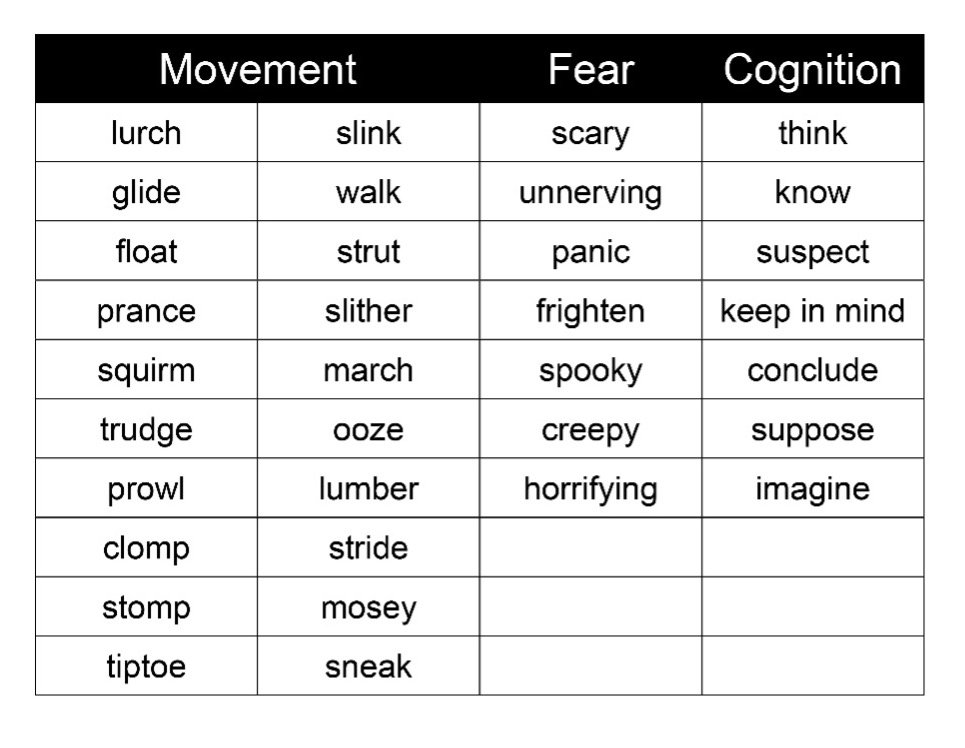

BOOK: Monsters Can Mosey by Gillia Olson (Picture Window Books)

DESCRIPTION

This book tells the story of a young monster named Frankie who is trying to figure out how she will set herself apart when taking part in an upcoming parade. Embedded into the story are multiple synonyms/shades of meaning for the concepts of movement, fear, and cognition as well as opportunities to target a wide variety of language and core standards.

METHOD

Students can try out their abilities to compare and contrast the different meanings of the vocabulary found in this story (see chart) through activities such as demonstrating how to clomp, ooze, tiptoe, and lurch, categorizing things that are scary versus spooky or creepy versus horrifying, or contributing more words to describe cognition to a word wall.

Figure 4. Monster's Can Mosey Activity.

You can extend this activity to target even more core standards and therapy targets by having students create titles for hypothetical (a great tier 2 vocabulary word) books following the pattern of Monsters Can Mosey (i.e., “noun” can “move” with alliteration). Some student-generated examples are: Duckings can Dawdle; Pandas can Prance, and Llamas can Lolligag. Then, try it using “fear” words (e.g., Spiders are Spooky, Tigers are Terrifying, Crabs are Creepy) and/or “cognition” words (e.g., Cats can Conclude, Iguanas can Imagine).

17. Do you have a suggestion for how to use wordless books in therapy that includes all of the principles for delivering efficient, effective language intervention?

Although it may seem counterintuitive, wordless books are a great vehicle for targeting a wide variety of language constructs. Vocabulary, comprehension, story grammar, meta-skills, and a number of other oral and written core communication skills are enhanced when students have to supply the words, sentences, and structure of the story that is embedded in the pictures of a “well-written” wordless book.

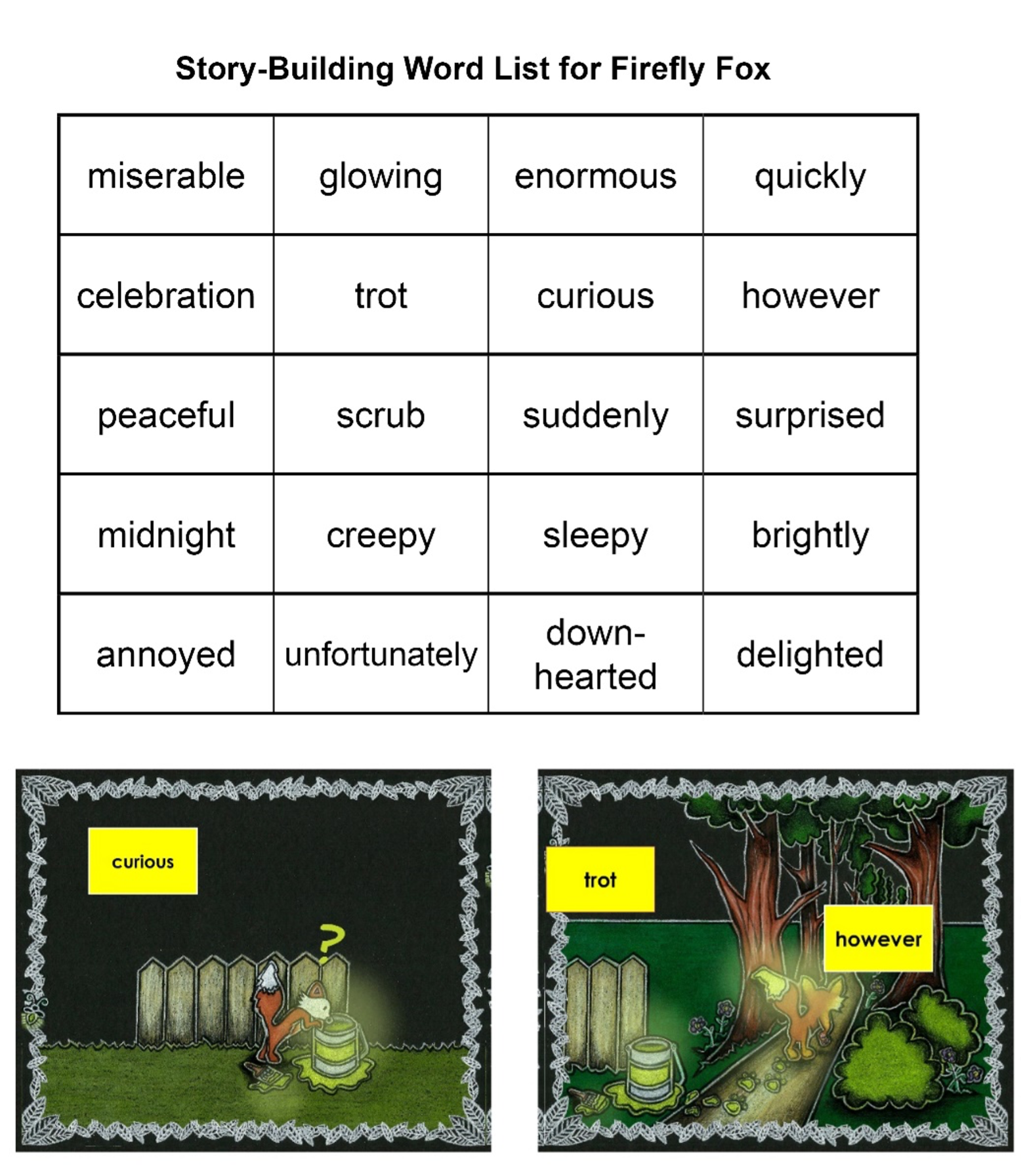

BOOK: Firefly Fox by Alexandra Bowser (Dynamic Resources)

METHOD

Identify a set of potential vocabulary words from a variety of semantic categories (based on the skill level of students) that help tell the story. This can include nouns, verbs, adjectives, conjunctions, compound words, double-meaning words, figurative language, etc. based on the language level or needs of the student/s. Students are given a stack of sticky notes and instructed to write one of the words on each note.

Next, students must determine which page of the wordless book would be appropriate for each word and stick the corresponding note on that page (all words must be used, and it's okay to use more than one word per page). Then, students retell the story making sure they incorporate the word/s they selected for each page into their narrative.

Sticky notes work very well here because they are easy to remove and “restick” if students decide they need to modify their story or word choice. This is also a terrific activity to do in groups, as students must engage in oral negotiations with their peers regarding what words to put on each page and how to retell the story.

Figure 5. Firefly Fox Activity.

18. Can you recommend a book for therapy that has rich vocabulary, a strong storyline, and targets multiple language and CC skills?

Yes! Here is one of my favorites! (I admit to bias because I train and show Arabian horses.)

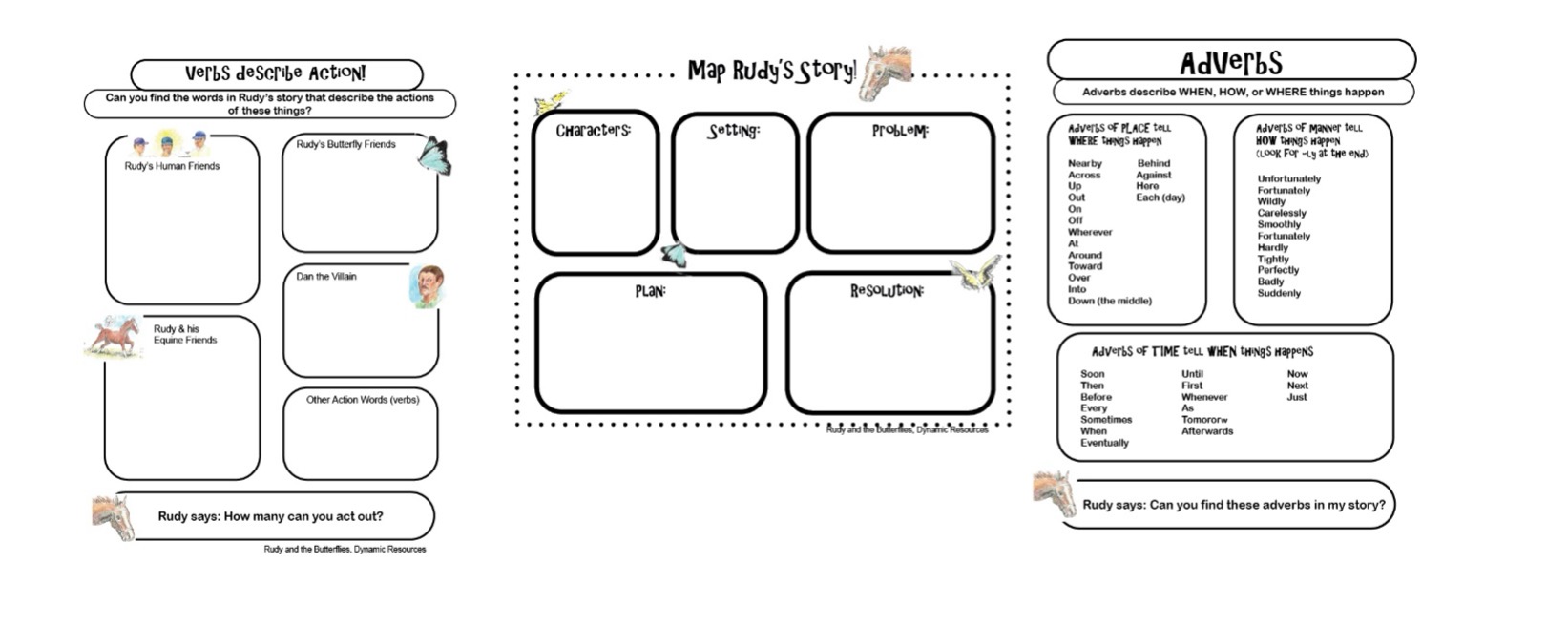

BOOK: Rudy and the Butterflies by Perry Flynn (Dynamic Resources)

DESCRIPTION

This book is based on the true-life story of the author who is an accomplished horseman as well as an SLP. It includes fantastically rich tier 2 vocabulary (e.g., elegant, charming, thwarted, swooped) and a storyline that includes a horse named Rudy, his butterfly friends, and a villain named Dan (who is “dastardly”). There is also a comprehensive library of free evidence-supported activities ready for download that target the numerous language and core-standard skills that are beautifully incorporated into the story. These include semantic categories (nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, conjunctions), story grammar development, synonyms, shades of meaning, figurative language (similes, idioms), theme-based vocabulary, alliteration, and applications to science, social studies, math, and more. Below are a few examples:

Figure 6. Rudy and the Butterflies Activity.

19. How can I share my superpowers outside of the therapy room?

Obviously, school-based SLPs don’t spend all their time in the therapy room–nor should they. There are multiple reasons to provide collaborative, integrated services in the classroom, such as meeting the mandates of LRE, providing opportunities for children to learn the skills they need in the places they need them, and ensuring that targeted skills are academically relevant and immediately useful. However, being in the classroom is also one of the best ways to share the value of your professional expertise with your colleagues, where we can provide real-time demonstrations of the critical role language plays in reading, writing, and academic success. (Note: all of the activities shared here work well in both small group and classroom settings.)

Core education standards across grade levels rely heavily on a variety of language-based constructs. As such, even a casual perusal of the CCSS (or any state standards) very quickly reveals various complex language skills embedded in the required skills and knowledge across grade levels. SLPs can expand their superpowers by playing a leadership role in explaining or clarifying the language-based underpinning of core skills and initiating engagement in collaborative discussion and efforts to facilitate student success in and out of the classroom (Ehren, 2012).

20. Where can I download the full lesson plans, templates, and extension activities? And are more available?

You can download as many of these materials as often as you like from the Dynamic Resources Learning Library at https://dynamic-resources.org/pages/dr-learning-library. You will also find many more book suggestions, lesson ideas, and extension materials here as well (all extension materials and lesson plans are free). Links to videos demonstrating several of these interventions, book lists that target specific language goals, and a variety of other clinical resources can be found under the “Free Resources” tab.

References

Catts, H., Fey, M., & Tomlin, B. (2002). A longitudinal investigation of reading outcomes in children with language impairments. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 45, 1142-115.

Clendon, S., Erickson, K., van Rensburg, R., & Amm, J. (2014). Shared Storybook Reading: An authentic context for developing literacy, language, and communication skills. Perspectives on Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 23(4), 182-191.

Ehren, B.J. (2000). Maintaining a therapeutic focus and shared responsibility for student success: Keys to in-classroom speech-language services. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 31, 219–229.

Ehren, B., Blosser, J., Roth, F., & Paul, D. (2012). Core commitment. The ASHA Leader, 17(4). https://doi.org/10.1044/leader.FTR1.17042012.10

Gibson, F. & Wolter, J. (2015). Morphological awareness intervention to improve vocabulary and reading success. Perspectives on Language Learning and Education, 22(4). https://doi.org/10.1044/lle22.4.147

Gough P. B., Tunmer W. E. (1986). Decoding, reading, and reading disability. Remedial and Special Education, 7(1), 6-10.

Hayes, D. P., & Ahrens, M. (1988). Vocabulary simplification for children: A special case of ‘motherese.’ Journal of Child Language, 15, 395-410.

Kamhi, A. G., & Catts, H. W. (2012). Language and reading disabilities (3rd ed.). Pearson.

Kim, A., Vaughn, S., Wanzek, J., & Wes, J. (2004). Graphic organizers and their effects on the reading comprehension of students with LD: A synthesis of research. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 37, 105–118.

McKeown, M. G., & Beck, I. L. (2003). Taking advantage of read-alouds to help children make sense of decontextualized language. In A. van Kleeck, S. Stahl, & E. Bauer (Eds.), On reading books to children (pp. 159-176). Erlbaum.

Nation, K., & Snowling, M. J. (2004). Beyond phonological skills: Broader language skills contribute to the development of reading. Journal of Research in Reading, 27(4), 342-356. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9817.2004.00238.

National Governors Association Center for Best Practices, Council of Chief State School Officers. (2010). Common Core State Standards. Washington DC: National Governors Association Center for Best Practices, Council of Chief State School Officers.

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. (2000). Report of the National Reading Panel. Teaching children to read: an evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction.

Power-deFur, L., & Flynn, P. (2012). Unpacking the standards for intervention. Perspectives on School-Based Issues, 13, 11–16. https://doi.org/10.1044/sbi13.1.11

Robertson, S. (2014) Building Better Readers. A Guide to Literacy Development for SLPs. Dynamic Resource, LLC.

Robertson, S. (2015). Read with Me! Stress-free strategies for building Language and Pre-Literacy Skills. Dynamic Resources

Robertson, S. (2017) There’s a book for that! The ASHA Leader, 22(12). https://doi.org/10.1044/leader.SCM.22122017.34

Roth, F. P., Speece, D. L. & Cooper, D. H. (2002). A longitudinal analysis of the connection between oral language and early reading. Journal of Educational Research, 95, 259–272.

Scarborough, H. (2001). Connecting early language and literacy to later reading (dis)abilities: Evidence, theory, and practice. In S. Neuman & D. Dickinson (Eds.), Handbook of early literacy (pp. 97–110). Guilford Press.

Schultz, J. (2016). Skills-Based Assessment of Core Communication Skills: K-2. Dynamic Resources.

Schultz, J. (2017). Skills-Based Assessment of Core Communication Skills: 3-5. Dynamic Resources.

Stanovich, K. E. (1986). Matthew effects in reading: Some consequences of individual differences in the acquisition of literacy. Reading Research Quarterly, 21(4), 360–407. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.21.4.1

Stothard, S. E., Snowling, M. J., Bishop, D. V. M., Chipchase, B. B., & Kaplan, C. A. (1998). Language impaired preschoolers: A follow-up into adolescence. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 41, 407–418.

Towson, J., Gallagher, P. and Bingam, G. (2016). Dialogic reading: Language and preliteracy outcomes for young children with disabilities. Journal of Early Intervention, 38(4) https://doi.org/10.1177/1053815116668643

Wallach, G., Charlton, & Christie. J. (2009). Making a Broader Case for the Narrow View: Where to Begin? Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 40(2). https://doi.org/10.1044/0161-1461(2009/08-0043)

Citation

Robertson, S. (2024). 20Q: Efficient and effective language intervention in the schools - embrace your superpower. SpeechPathology.com. Article 20642. Available at www.speechpathology.com