From the Desk of Ann Kummer

Dyslexia is a specific learning disorder that involves difficulty reading due to differences in the areas of the brain that process written language. Affected individuals have difficulties with many aspects of reading, including associating sounds with letters, spelling, word recognition, and comprehension. Dyslexia can occur in individuals with normal or even above average intelligence.

Many speech-language pathologists (SLPs) evaluate and treat dyslexia as part of their practice. Therefore, I am happy to provide you with this very informative article called Dyslexia: Foundations and Clinical Practice by Linda Lombardino and Laurie Gauger.

Here is some information about these authors:

Linda Lombardino, PhD, CCC-SLP, is a professor of speech-language pathology and special education who has worked at the University of Florida for over 40 years. Her area of clinical practice and research is development language disorders with a specialization in dyslexia. She has published numerous papers on the topic, authored Assessing and Differentiating Reading and Writing Disorders: Multidimensional Model (2011) and co-authored the Assessment of Literacy and Language (ALL; 2020)

Laurie Gauger, PhD, CCC-SLP, is a Clinical Associate Professor in the Department of Speech, Language, and Hearing Sciences at the University of Florida. She teaches undergraduate and graduate courses in pediatric language development and disorders. Dr. Gauger also directs the UF Reading Disabilities Program, where she evaluates and provides intervention to children with reading difficulties, including dyslexia. Her research interests are in identifying early markers of reading disabilities. Dr. Gauger served as Director of the Bachelor of Health Science Program in Communication Sciences and Disorders (BHS-CSD) for six years, resigning in June 2022.

This informative article will help readers to better understand the foundational deficits that characterize dyslexia. It will also help readers learn about accepted method for instructing students who have dyslexia.

Now…read on, learn, and enjoy!

Ann W. Kummer, PhD, CCC-SLP, FASHA, 2017 ASHA Honors

Contributing Editor

Browse the complete collection of 20Q with Ann Kummer CEU articles at www.speechpathology.com/20Q

20Q: Dyslexia - Foundations and Clinical Practice

Learning Outcomes

After this course, readers will be able to:

- Define dyslexia and its prevalence

- Identify early warning signs of dyslexia

- Identify foundational and diagnostic assessment tasks important for diagnosing dyslexia

PART I: Foundations of Dyslexia

1. How is dyslexia defined?

Developmental dyslexia (DD) is a lifelong neurodevelopmental language disorder that often runs in families and is characterized by primary deficits in word-level reading and spelling that are unexpected given the child’s other cognitive achievements and literacy learning opportunities. These deficits impact word-level reading accuracy and speed and oral reading fluency and often interfere with reading comprehension.

Over the last two decades, dyslexia has been defined in different ways within the US and internationally (Vaughn et al., 2024). The definition most commonly used in the US literature and in state-level legislation for DD is the one adopted by consensus among the International Dyslexia Association, the National Center for Learning Disabilities and the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development.

Dyslexia is a specific learning disability that is neurobiological in origin. It is characterized by difficulties with accurate and/or fluent word recognition and by poor spelling and decoding abilities. These difficulties typically result from a deficit in the phonological component of language that is often unexpected in relation to other cognitive abilities and the provision of effective classroom instruction. Secondary consequences may include problems in reading comprehension and reduced reading experience that can impede growth of vocabulary and background knowledge.” Lyon, 2003, p. 2).

2. How is dyslexia identified?

Reading deficits can result from any number of factors. Not all reading deficits are due to neurodevelopmental differences and not all reading disabilities represent dyslexia (Aaron & Joshi, 1999; Cutting et al., 2013). It is important to recognize that both biological and environmental factors play a role in the degree to which dyslexia symptoms manifest in students reading and spelling skills (Catts & Petscher, 2022). Dyslexia runs in families (Gilger et al., 1996) with an estimated heritability between 40 and 60% (Raskind et al., 2013). Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder co-occurs with dyslexia between 30 and 50% on the time (Wilcutt et al., 2003).

Several researchers (Vaughn et al., 2024; Wagner et al., 2020) emphasize that dyslexia is most accurately identified when hybrid models, based on multiple indices and criteria, are used and address three potential causal factors: (1) phonological processing skill impacting word-level reading ability; (2) family history and; (3) type of reading instruction to differentiate struggling readers who respond to evidence-based instruction from those and those who are resistant to intervention in spite of appropriate instructional methods.

3. What is the prevalence of developmental dyslexia?

Prevalence statistics on dyslexia vary from around 5 to 20% (Wagner et al., 2020; Pennington & Bishop, 2009) depending on the nature of data collected to study prevalence. A more precise statistic from a recent systematic review and meta-analysis of developmental dyslexia studies in primary school children from the 1950s to 2021 suggests a rate close to 7% for school-age children (Yang et al., 2022).

4. What is the status of dyslexia legislation in the US?

Dyslexia legislation exists at both the federal and state levels. Under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), dyslexia is listed as one of the conditions that falls within the category of a “specific learning disability” (U.S. Office of Education, 1968). A synopsis of federal-level policy on dyslexia can be found in Zagata (2024). As of 2023, every state in the US has some form of dyslexia legislation. A list of each state’s legislation can be found at https://luca.ai/blog/article/12. As noted in this blog, legislation from state to state is not uniform and some states have much more explicit policies than others.

5. What is phonological processing, and what role does it play in identifying dyslexia?

A core deficit in the behavioral profiles of persons who have dyslexia appears to be in the domain of phonological processing (Rack et al., 1992; Ramus, 2003; Snowling, 1995; Wolf et al., 2002) which constitutes a range of skills needed to represent, store, and recall the sounds in one’s language. The term phonological processing, as used in literacy literature, most often refers to three related constructs: Phonological awareness (PA) - the metalinguistic ability to isolate and manipulate sounds in one’s language; phonological memory (PM) - the ability to maintain linguistic units in memory for a short period of time; and rapid automatized naming (RAN) - the ability to rapidly retrieve names of familiar items (e.g., letter, digits, colors) presented in a serial array.

Across several studies, measures of knowledge letter sounds (LSK) phonological awareness (PA), rapid automatized naming (RAN) are the strongest early predictors of reading ability (Caravolas et al., 2013; Ozernov-Palchik et al.,2016) and often used to identify a “dyslexia profile” in children who are struggling to learn to read. However, there is no one single deficit profile that characterizes dyslexia or risk for dyslexia (Pennington et al., 2012). For example, some children have deficits on PA measures alone, some have deficits on RAN measures alone, and some have deficits on both PA and RAN measures (Ozernov-Palchik et al.,2016) in addition to struggling with word-reading and spelling acquisition.

6. Does dyslexia occur in all languages?

Dyslexia occurs in all languages that have an orthography (Reis et al, 2020). The phonological processing skills described above appear to serve as good predictors of reading across all alphabet orthographies studied. Letter or symbol knowledge appears to be the single best predictor of reading acquisition across all orthographies studied (Landerl et al., 2021).

7. What are the neurobiological indicators of dyslexia?

Several brain imaging studies have shown different patterns of cortical activity in children in what is often referred to as the “reading network” in the brain. This network refers to the parietal-temporal-occipital regions and the inferior frontal areas in the left hemisphere of the brain (Kearns et al., 2019). There is some evidence that differences observed may arise from lower-levels of processing in primary sensory areas (Clark et al., 2014, Kuhl et al., 2020.)

8. What are some common myths about dyslexia?

There are a variety of misconceptions surrounding dyslexia that prevail today despite many of them being disputed by a large body of research over the years. Too often, these misconceptions are held by the public, educators, and speech-language pathologists (Gini et al., 2021; Torrijos-Muelas et al., 2021; Krimm, McDaniel, & Schuele, 2023). A few of the more popular myths that surround dyslexia as reported by Dyslexia Help at the University of Michigan (https://dyslexiahelp.umich.edu) are listed below:

Dyslexia can be outgrown. Dyslexia is a life-long issue, however with appropriate intervention these individuals can learn to read. Usually, they become accurate readers but continue to show deficits in reading speed.

Dyslexia cannot be diagnosed until third grade. Dyslexia can be accurately diagnosed in children as young as 5-6 years of age by professionals with the proper training/education. With early diagnosis, children with dyslexia can begin to receive effective reading instruction which can help them stay as close to grade level in reading as possible. For this reason, it is important that parents, early education teachers, and pediatricians are aware of the early signs of dyslexia and make the proper referrals.

Dyslexia is a medical diagnosis. Dyslexia is a specific learning disability and is not a medical diagnosis. Dyslexia is diagnosed through a variety of behavioral tests that examine oral and written language skills, including phonological processing, word-level reading, spelling, writing skills, reading comprehension, and listening comprehension.

People with dyslexia see words backwards. Dyslexia is not a vision problem. As noted above, a core deficit of dyslexia is in the domain of phonological processing which underlies difficulties in word reading and spelling.

Any child who reverses letters and numbers has dyslexia. It is quite common for typically-developing children to reverse letters and numbers until the end of second grade. Children who demonstrate letter and/or number reversals beyond this period are at risk for dyslexia.

Individuals with dyslexia are not very smart. There is no relationship between dyslexia and intelligence. Individuals with dyslexia can have average to above average IQs. As the definition of dyslexia states, it is a disorder that is unexpected given the individual’s cognitive and language abilities and opportunities to learn to read.

Dyslexia can be cured or helped by brain games, glasses with tinted lenses, colored overlays, or vision exercises. Dyslexia cannot be cured and there is no scientific evidence that any of these things help a child learn to read. Research supports a structured literacy approach as the most effective way to teach reading and spelling to individuals with dyslexia.

PART II: Clinical and Educational Practices

9. Why are speech-language pathologists uniquely qualified to identify young children at risk for dyslexia?

As noted in ASHA's (2001) Ad Hoc committee paper entitled, Roles and Responsibilities of Speech-Language Pathologist with Respect to Reading and Writing in Children and Adolescents, oral language is the foundation for learning to read. SLPs possess the knowledge needed to examine the range of spoken language skills that are foundational to later literacy and to differentiate strengths and weaknesses across these component skills of oral language (i.e., vocabulary, comprehension) and across other skills that fall under the overarching domain of phonological processing and known to predict reading ability.

An understanding of all components of the child’s oral language abilities is essential in determining the nature of a reading ability. Impairments in oral language put children at risk for dyslexia (Catts et al., 1999; Adolf & Hogan, 2018). One fundamental question that SLPS need to address is, Does the child show difficulties in phonological processing and other literacy related skills such as fluent word recognition and nonword decoding in spite of typical receptive and expressive language skills (pattern common in children who have dyslexia) or does the child exhibit difficulties with receptive and/or expressive spoken language skills in addition to difficulties with component skills of reading (pattern in children with a broader language-based reading disability).

10. What are early signs of dyslexia that place a child at risk?

There are a number of signs that young children can demonstrate that place them at risk for dyslexia. It is important to keep in mind that these signs are associated with dyslexia if they are unexpected for the individual’s age, educational level, or cognitive abilities. Because dyslexia runs in families, a family history of reading and/or spelling difficulties is a major risk factor at any age. For more information about early signs of dyslexia, please refer to the Reading Rockets website (www.readingrockets.org). Below are some other common early signs that place a child at risk for dyslexia:

Preschool years:

- Produces first words and 2-word combinations later than expected

- History of speech-sound errors

- Difficulty reciting nursery rhymes

- Difficulty learning the alphabet and numbers

- Difficulty learning the days of the week, colors, and shapes

- Difficulty recognizing the letters in his/her own name

- Difficulty telling or retelling a story in the correct sequence

Kindergarten and first grade:

- Difficulty segmenting spoken words into syllables and later into sounds (t-o-p)

- Slow to learn the connection between letters and sounds (phonics)

- Difficulty decoding simple, regular words, such as “mop”.

- Difficulty spelling simple regular words

- Trying to guess the target word on a page based on the initial letter or context of the sentence

- Complains that reading is hard or avoids reading

Beyond first grade:

- Very few sight words or words can be read automatically without decoding

- Difficulty decoding regular words

- Guesses written words based on initial letter or context of sentence

- Difficulties with reading comprehension, but not with listening comprehension

- Continues to use phonetic spellings into third grade (e.g., plate as plat or when as wen) instead of producing conventional spellings.

- Difficulty reading and spelling words with vowel teams (boat) or consonant digraphs (match)

- Transposes numbers and confuses arithmetic signs (+ - x / =)

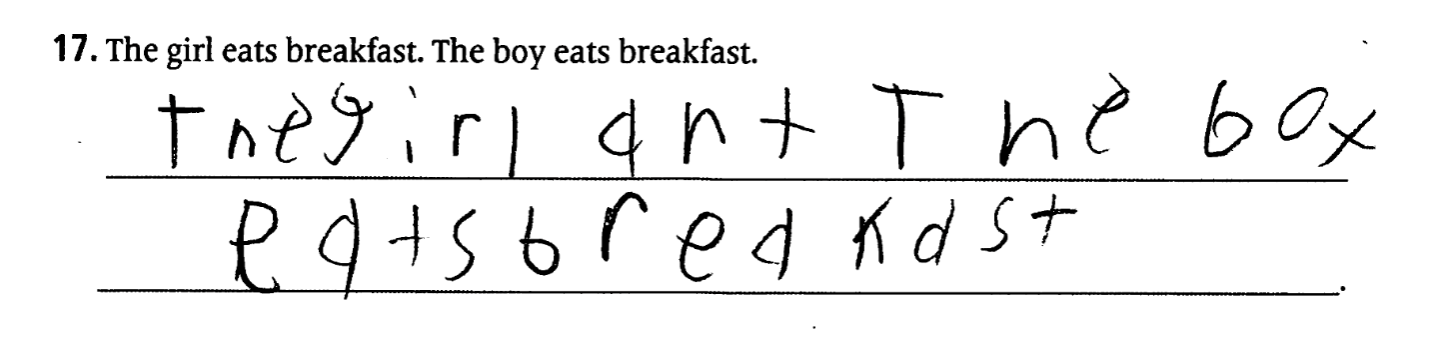

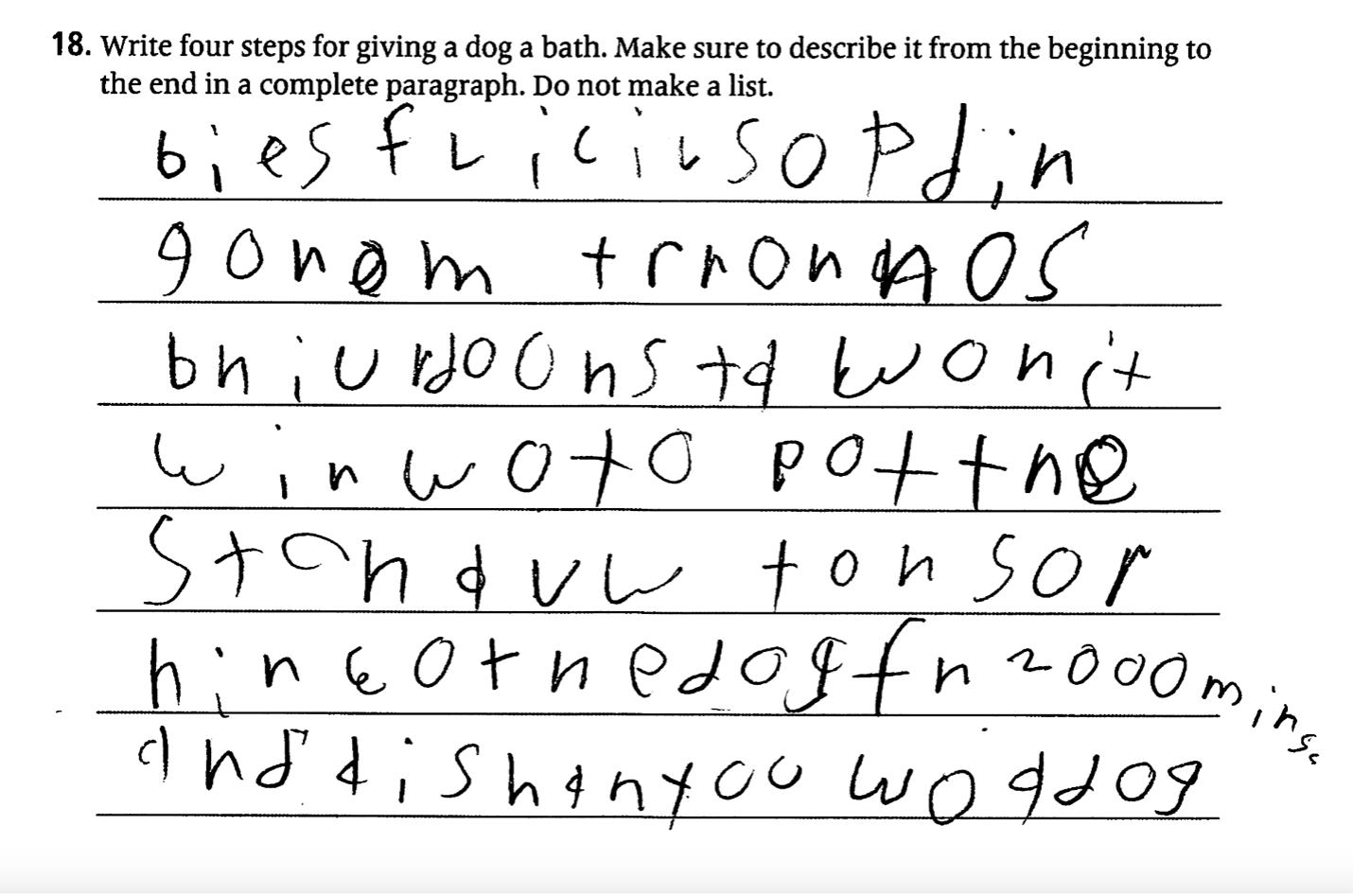

- Writing is characterized by spelling, capitalization and punctuation errors

- Written paragraphs are not well organized, contain unexpected spelling errors and simple sentence structure

- Difficulties saying multisyllable words, such as aluminum or refrigerator.

- Shows frustration when completing reading and writing tasks and avoids reading and writing.

- Difficulties memorizing rote math facts such as the times tables

11. What kinds of assessments are included in an evaluation to diagnose a reading disability, such as dyslexia?

Reading is a language-based skill and as such, oral (listening and speaking) and written (reading and writing) language skills should be evaluated to determine the underlying cause of the reading difficulties. Examining both oral and written language skills allows for the differential diagnosis of the reading disorder. Specific oral and written language skills to measure include:

- Alphabet knowledge (for children in pre-k through first grade)

- Phonological processing (PA, PM, RAN)

- Rapid automatic naming

- Decoding and decoding fluency

- Sight word reading and sight word reading fluency

- Oral reading fluency

- Reading comprehension

- Spelling

- Sentence and paragraph writing

- Listening comprehension of various vocabulary and linguistic structures

- Oral expression

12. What does a typical profile of a student with dyslexia look like on a norm-referenced battery?

Two profiles of students who were diagnosed with dyslexia are shown below.

Case 1: PJ, an 8-year, 6-month-old female, has just completed 2nd grade. She has an IEP for a speech impaired and a diagnosis of ADHD. She has been receiving Tier 2 reading instruction daily for over 5 months in the classroom with a reading specialist using a structured literacy approach with an emphasis on phonics instruction. PJ is not showing expected gains on regularly administered progress monitoring probes. She has a positive family history for reading disability.

| Scaled & Standard Scores | Percentile Rankings | Interpretation of scores relative to test norms |

Assessment of Literacy and Language |

|

|

|

Letter knowledge | 1 | 0.4 | Depressed |

Rhyme knowledge | 5 | 5 | Depressed |

Elision | 6 | 9 | Depressed |

Phonics knowledge | 2 | 1 | Depressed |

Sound categorization | 3 | 1 | Depressed |

Sight word recognition | 4 | 2 | Depressed |

Emergent Literacy Index | 49 | <0.1 | Depressed |

Basic concepts | 11 | 63 | Average |

Receptive vocabulary | 13 | 84 | High average |

Parallel sentence production | 11 | 63 | Average |

Word relationships | 9 | 37 | Average |

Listening comprehension | 8 | 25 | Low average |

Spoken Language Index | 98 | 47 | Average |

OWL-II:RC/WE |

|

|

|

Reading comprehension | 63 | 1 | Depressed |

Written expression | unable to complete |

| Depressed |

ALL: The Assessment of Literacy and Language (Lombardino, Lieberman, & Brown, 2020)

OWLS-II: Oral and Written Language Scales-II:RC/WE (Carrow-Woolfolk, 2011)

Case 2: JM, a nine-year-one-month-old male, just completed third grade and was promoted to fourth grade. He received Tier 2 reading instruction for most of third grade but made little progress. He does not have an IEP and has not been identified as having a reading disability; however, he was previously diagnosed with ADHD and is on medicine for attention difficulties. JM has a positive family history of reading difficulties.

| Scaled & Standard Score | Percentile Rankings | Interpretation of scores relative to test norms |

CTOPP-2 |

|

|

|

Elision | 6 | 9 | Below Average |

Phoneme Isolation | 8 | 25 | Low Average |

Blending Words | 9 | 37 | Average |

Phonological Awareness Composite | 86 | 18 | Below Average |

Memory for Digits | 9 | 37 | Average |

Nonword Repetition | 8 | 25 | Low Average |

Phonological Memory Composite | 92 | 30 | Average |

Rapid Number Naming | 5 | 5 | Depressed |

Rapid Letter Naming | 6 | 9 | Depressed |

Rapid Naming Comp | 73 | 3 | Depressed |

TOWRE-2 |

|

|

|

Sight Word Efficiency | 55 | <1 | Very Depressed |

Phonemic Decoding Efficiency | 62 | <1 | Very Depressed |

Total Word Reading Efficiency | 56 | <1 | Very Depressed |

GORT-5 |

|

|

|

Rate | 1 | <1 | Very Depressed |

Accuracy | 1 | <1 | Very Depressed |

Fluency | 1 | <1 | Very Depressed |

Reading Comprehension | 3 | 1 | Very Depressed |

Oral Reading Index | 57 | <1 | Very Depressed |

TWS-2 |

|

|

|

Spelling | 50 | <1 | Very Depressed |

OWLS-II: WE |

|

|

|

Written Expression | 45 | <1 | Very Depressed |

OWLS-II:LC |

|

|

|

Listening Comprehension | 101 | 53 | Average |

CTOPP-2: Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing-2 (Wagner, Torgesen, Rashotte & Pearson, 2013); TOWRE-2: Test of Word Reading Efficiency-2 (Torgesen, Wagner, & Rashotte, 2012); GORT-5: Gray Oral Reading Test-5 (Wiederholt & Bryant, 2012); TWS-2: Test of Written Spelling (Larsen, Hammill, & Moats, 2013); OWLS-II: Oral and Written Language Scales-II (Carrow-Woolfolk, 2011); written expression (WE); Listening Comprehension (LC); CELF-5: Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals (Wiig, Semel, & Secord, 2013).

13. What are the diagnostic codes used for developmental dyslexia?

Two types of diagnostic codes are typically used to indicate a diagnosis of developmental dyslexia. The DSM-5 defines dyslexia as a specific learning disorder with impairment in reading, including word reading accuracy, reading fluency, and reading comprehension. When writing (spelling, grammar, punctuation, and composition) is also affected, this is identified as a specific learning disorder with impairment in written expression. Because individuals with dyslexia typically have both reading and writing deficits, these diagnoses are usually combined and written as a specific learning disorder with impairment in reading and writing.

The International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10-CM) is a system of billable codes used for reimbursement. The ICD-10-CM codes for dyslexia are F81.0 (specific learning disorder with impairment in reading) and F81.1 (specific learning disorder with impairment in written expression). It is common to see both the DSM-5 and ICD-10-CM codes included in diagnostic reports.

14. What kind of reading instruction works best with children with dyslexia?

According to experts in reading and dyslexia, the most effective type of reading instruction is a Structured Literacy approach. A structured literacy approach has been found to be effective in teaching all individuals to read, not just those with dyslexia. Structured literacy is a type of reading approach that is systematic, cumulative, explicit and diagnostic in nature. It specifically addresses decoding skills and other aspects of language and reading including phoneme awareness, sound-symbol associations, syllable types, orthography, morphology, syntax, and semantics.

15. What are some common accommodations for individuals with dyslexia?

According to the International Dyslexia Association, “accommodations are adjustments made to allow a student to demonstrate knowledge, skills, and abilities without lowering learning performance or expectations and without changing what is being measured.” (pg. 1 Accommodations for Students with Dyslexia Fact Sheet). Accommodations help students participate meaningfully in grade-level instruction. Accommodations should be selected based on the student’s individual needs with input from the student, teacher, and parent. For students in elementary and secondary school, accommodations are provided for through an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) or a 504 Plan. There are four main types of accommodations: presentation, response, setting and timing/scheduling.

- Presentation accommodation refers to how information is presented to the student. They include the addition of verbal instructions, visual prompts such as highlighted text, speech-to-text software, and spell check.

- Response accommodations provide students with alternative ways to complete assignments and tests. Examples include dictating to a scribe, pointing to response choices or typing responses.

- Setting accommodations change the location in which a test or assignment is given or the conditions of the setting. Examples include individual or small group instruction and distraction-free room for testing

- Timing and scheduling accommodations change the length of time allowed for completion of a test or assignment or how it is organized, such as taking a test over several sessions or just one session and breaking down a long assignment into small chunks.

16. Is it ever too late to learn how to read?

The simple answer is no. According to Sally Shaywitz, most children and adults with dyslexia can learn to read, but it will take more effort. With a structured literacy approach, individuals with dyslexia can become accurate readers, but they typically will remain slow readers. That is why the accommodation of extended time is so helpful to individuals with dyslexia. It is important to note that the older the individual is, the more difficult it will be to learn to read. Several studies have found that children who are poor readers at the end of first grade almost never acquire average-level reading skills by the end of elementary school (Francis, Shaywitz, Stuebing, Shaywitz, and Fletcher, 1996; Juel, 1988; Shaywitz et al., 1999; Torgesen and Burgess, 1998).

17. Is grade retention recommended for children with dyslexia?

Many schools recommend retention as a form of intervention to improve academic performance, but research indicates that it does just the opposite. The rationale for retention is that students with dyslexia just need more time to learn to read and having them repeat the grade and receive the same instruction a second time will give them the time they need to catch on. Retention in general is not recommended to improve academic performance, and it is specifically not recommended for children with dyslexia. Study after study has found that retention not only doesn’t help students with dyslexia, but it can also be harmful. A systematic review of studies examining the effects of retention found that most students did not make improvements during their retention year, and those that did improve, lost their gains within a few years (Jimerson, 2001). Retention also increases the chances that a child will drop out of school. Providing the student with a structured literacy approach to reading instruction as early as possible, along with class and test accommodations to support them as they increase their reading skills, has the most positive effects on a student’s academic, social, and emotional development.

18. What are some ways that parents can help their children be prepared to learn to read when they start school?

There are many things that parents can do in their everyday lives to help their children develop the skills that support reading. Because reading is a language-based skill, many of these activities have the benefit of also supporting oral language development. One of the most important activities that parents can do with their children is to read to them. It is never too early to start reading to children and parents should make reading with their children a part of their everyday routine. Shared book reading between a parent and child not only supports oral language growth, by exposing their children to new vocabulary and sentence structures, but also increases familiarity with letters, words, and how we read. Below are additional suggestions outlined by Reading Rockets for parents of young children:

- While reading stories, name pictures in the book, ask questions, and discuss what is happening in the story

- Finger-point read (point to words as you read them out loud) to show children how printed words map to spoken words. This behavior also shows children that we read a page from top to bottom and from left to right.

- Point out printed words in the environment

- Listen to and recite nursey rhymes

- As children begin to learn the alphabet, have them point out letters on the page, in the environment, and in their name.

19. What are some resources for parents of children with dyslexia?

- Yale Center for Creativity and Dyslexia www.dyslexia.yale.edu

- Florida Center for Reading Research www.fcrr.org

- Dyslexia Help at the University of Michigan www.dyslexiahelp.umich.edu.

- Reading Rockets www.readingrockets.org

- International Dyslexia Association www.dyslexiaida.org

- Learning Disabilities Association of America www.ldaamerica.org

- National Center on Improving Literacy www.improvingliteracy.org

20. What are some current references that will help me become knowledgeable about the state-of-the-art research and educational practices in dyslexia?

- Adlof, S. M., & Hogan, T. P. (2018). Understanding dyslexia in the context of developmental language disorders. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 49(4), 762-773.

- Al Otaiba, S., McMaster, K., Wanzek, J., & Zaru, M. W. (2023). What we know and need to know about literacy interventions for elementary students with reading difficulties and disabilities, including dyslexia. Reading Research Quarterly, 58(2), 313-332.

- Catts, H. W., & Petscher, Y. (2018). Early identification of dyslexia. Achieving Literacy, 33.

- Clemens, N. H., & Vaughn, S. (2023). Understandings and misunderstandings about dyslexia: Introduction to the special issue. Reading Research Quarterly, 58(2), 181-187.

- Fletcher, J. M., Francis, D. J., Foorman, B. R., & Schatschneider, C. (2021). Early detection of dyslexia risk: development of brief, teacher-administered screens. Learning Disability Quarterly, 44(3), 145-157.

- Kearns, D. M., Hancock, R., Hoeft, F., Pugh, K. R., & Frost, S. J. (2019). The neurobiology of dyslexia. Teaching Exceptional Children, 51(3), 175-188.

- Krimm, H., McDaniel, J., & Schuele, C. M. (2023). Conceptions and misconceptions: what do school-based speech-language pathologists think about dyslexia? Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 54(4), 1267-1281.

- Vaughn, S., Miciak, J., Clemens, N., & Fletcher, J. M. (2024). The critical role of instructional response in defining and identifying students with dyslexia: A case for updating existing definitions. Annals of Dyslexia, 1-12.

- Shanahan, T. (2023). A review of the evidence on tier 1 instruction for readers with dyslexia. Reading Research Quarterly, 58(2), 268-284.

References

Aaron, P. G., Joshi, M., & Williams, K. A. (1999). Not all reading disabilities are alike. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 32(2), 120-137.

Adlof, S. M., & Hogan, T. P. (2018). Understanding dyslexia in the context of developmental language disorders. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 49(4), 762-773.

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2001). Roles and responsibilities of speech-language pathologists with respect to reading and writing in children and adolescents [Position Statement]. Available from www.asha.org/policy.

Catts, H. W., Fey, M. E., Zhang, X., & Tomblin, J. B. (1999). Language basis of reading and reading disabilities: Evidence from a longitudinal investigation. Scientific Studies of Reading, 3(4), 331-361.

Catts, H. W., & Petscher, Y. (2022). A cumulative risk and resilience model of dyslexia. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 55(3), 171-184.

Cutting, L. E., Clements-Stephens, A., Pugh, K. R., Burns, S., Cao, A., Pekar, J. J., ... & Rimrodt, S. L. (2013). Not all reading disabilities are dyslexia: distinct neurobiology of specific comprehension deficits. Brain Connectivity, 3(2), 199-211.

Francis, D. J., Shaywitz, S. E., Stuebing, K. K., Shaywitz, B. A., & Fletcher, J. M. (1996). Developmental lag versus deficit models of reading disability: A longitudinal, individual growth curves analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 88(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.88.1.3.

Gilger, J. W., Hanebuth, E., Smith, S. D., & Pennington, B. F. (1996). Differential risk for developmental reading disorders in the offspring of compensated versus noncompensated parents. Reading and Writing, 8, 407-417.

Gini, S., Knowland, V., Thomas, M.S.C., & Van Herwegen, J. (2021). Neuromyths about neurodevelopmental disorders: Misconceptions by educators and the general public. Mind, Brain, and Education, 15(4), 289-298. https://doi,org/10.1111/mbe.12303.

Jimerson, S. R. (2001). Meta-analysis of grade retention research: Implications for practice in the 21st century. School Psychology Review, 30(3), 420–437.

Juel, C. (1988). Learning to read and write: A longitudinal study of 54 children from first through fourth grades. Journal of Educational Psychology, 80(4), 437–447. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.80.4.437.

Krimm, H., McDaniel, J., & Schuele, C. M. (2023). Conceptions and Misconceptions: What Do School-Based Speech-Language Pathologists Think About Dyslexia? Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 54(4), 1267-1281. https://doi.org/10.1044/2023_LSHSS-22-00199.

Clark, K. A., Helland, T., Specht, K., Narr, K. L., Manis, F. R., Toga, A. W., & Hugdahl, K. (2014). Neuroanatomical precursors of dyslexia identified from pre-reading through to age 11. Brain, 137(12), 3136-3141.

Kuhl, U., Neef, N. E., Kraft, I., Schaadt, G., Dörr, L., Brauer, J., ... & Skeide, M. A. (2020). The emergence of dyslexia in the developing brain. Neuroimage, 211, 116633.

Landerl, K., Castles, A., & Parrila, R. (2021). Cognitive precursors of reading: a cross-linguistic perspective. Scientific studies of reading, 26(2), 111–124.

Lyon, G. R., Shaywitz, S. E., & Shaywitz, B. A. (2003). A definition of dyslexia. Annals of dyslexia, 53, 1–14.

Raskind, W. H., Peter, B., Richards, T., Eckert, M. M., & Berninger, V. W. (2013). The genetics of reading disabilities: from phenotypes to candidate genes. Frontiers in psychology, 3, 601.

Pennington, B. F., Santerre-Lemmon, L., Rosenberg, J., MacDonald, B., Boada, R., Friend, A., Leopold, D. R., Samuelsson, S., Byrne, B., Willcutt, E. G., & Olson, R. K. (2012). Individual prediction of dyslexia by single versus multiple deficit models. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 121(1), 212–224.

Reis, A., Araújo, S., Morais, I. S., & Faísca, L. (2020). Reading and reading-related skills in adults with dyslexia from different orthographic systems: A review and meta-analysis. Annals of Dyslexia, 70(3), 339-368.

Shaywitz, S. E., Fletcher, J. M., Holahan, J. M., Shneider, A. E., Marchione, K. E., Stuebing, K. K., ... & Shaywitz, B. A. (1999). Persistence of dyslexia: The Connecticut longitudinal study at adolescence. Pediatrics, 104(6), 1351-1359. doi: 10.1542/peds.104.6.1351. PMID: 10585988.

Snowling, M. J. (1995). Phonological processing and developmental dyslexia. Journal of Research in Reading, 18(2), 132–138.

Torgesen, J. K., & Burgess, S. R. (1998). Consistency of reading-related phonological processes throughout early childhood: Evidence from longitudinal-correlational and instructional studies. Word recognition in beginning literacy, 161, 188.

Torrijos-Muelas, M., Gonzalez-Villora, S., & Bodoque-Osma, A.R. (2021). The persistence of neuromyths in the educational settings: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, Article 591923.

Wagner, R. K., & Torgesen, J. K. (1987). The nature of phonological processing and its causal role in the acquisition of reading skills. Psychological Bulletin, 101(2), 192–212.

Wagner, R. K., Zirps, F. A., Edwards, A. A., Wood, S. G., Joyner, R. E., Becker, B. J., Liu, G., & Beal, B. (2020). The Prevalence of Dyslexia: A New Approach to Its Estimation. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 53(5), 354-365.

Vaughn, S., Miciak, J., Clemens, N., & Fletcher, J. M. (2024). The critical role of instructional response in defining and identifying students with dyslexia: A case for updating existing definitions. Annals of Dyslexia, 1-12.

Yang, L., Li, C., Li, X., Zhai, M., An, Q., Zhang, Y., ... & Weng, X. (2022). Prevalence of developmental dyslexia in primary school children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Sciences, 12(2), 240. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci12020240

Zagata, E. (2024). DLD Policy Brief: A Synopsis of Federal-Level Dyslexia Law. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 39(2), 57-59. https://doi.org/10.1177/09388982241230759

Citation

Lombardino, L. & Gauger, L. (2024). 20Q: Dyslexia - foundations and clinical practice. SpeechPathology.com. Article 20692. Available at www.speechpathology.com