From the Desk of Ann Kummer

I am so excited about this 20Q article because there continues to be a lot of confusion among both audiologists and speech-language pathologists regarding the diagnosis of a “processing disorder.” We use terms such as “auditory processing disorder,” “central auditory processing disorder,” “language processing disorder” and “phonemic processing disorder,” but we are not always clear on how these disorders and terms are differentiated. Fortunately, Dr. Gail J. Richard, Ph.D., CCC-SLP will answer our questions about processing disorders with this 20Q article.

Here’s a little information about Dr. Richard. She is emeritus professor at Eastern Illinois University in Charleston, IL, where she was on the faculty for 37 years specializing in childhood developmental language disorders, such as autistic spectrum disorders, auditory/language processing, executive functions, and selective mutism. She also founded the Autism Center at the university and a program for college students with autism spectrum disorder – Students with Autism Transitional Education Program (STEP). She has numerous publications and is a frequent conference presenter, sharing her practical clinical perspective. Professional awards include Honors of the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, recipient of the Illinois Clinical Achievement Award, and multiple teaching awards. She has also held many leadership positions in professional organizations, including President of the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association in 2017.

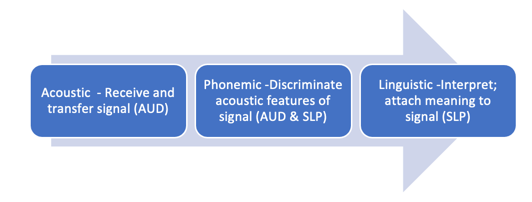

In this article, Dr. Richard will use a continuum to explain processing disorders that involve acoustic, phonemic, and/or linguistic aspects. She discusses the responsibilities of an audiologist and speech-language pathologist in relation to processing disorders. Most importantly, she gives examples of specific skills and compensatory strategies that can be used for the different types of processing disorders.

This course will definitely help you to differentiate processing disorders based on acoustic, phonemic, or linguistic aspects. As a result, your assessment and treatment will become more focused and effective.

Now…read on, learn, and enjoy!

Ann W. Kummer, PhD, CCC-SLP, FASHA, 2017 ASHA Honors

Contributing Editor

Browse the complete collection of 20Q with Ann Kummer CEU articles at www.speechpathology.com/20Q

20Q: A Continuum Approach for Sorting Out Processing Disorders

Learning Outcomes

After this course, readers will be able to:

- Define and differentiate auditory and language processing disorders

- Utilize a continuum to describe different aspects of processing into acoustic, phonemic, and linguistic

- Identify the responsibilities of an audiologist and speech-language pathologist in relation to processing disorders

- List examples of specific skills and compensatory strategies within the acoustic, phonemic, and linguistic aspects of processing

Gail Richard

Gail Richard1. What is a “processing disorder?”

A “processing disorder” is actually a generic term that is used by many professionals to describe a variety of learning problems. Psychologists, teachers, audiologists, and speech-language pathologists all introduce the term when an individual is having difficulty accurately understanding and responding to sensory information. Unfortunately, there are a number of different skills that are encompassed within the term “processing disorder “which leads to a lot of confusion.

2. Are there different types of processing disorders?

Absolutely! We process information from all our sensory systems. We can close our eyes and taste, smell or feel something to try and figure out what it is. In aphasia literature, we talk about agnosia – when you receive a stimulus but can’t comprehend or make sense of it. It is easier to comprehend in the visual (sight), tactile (touch), olfactory (smell), and gustatory (taste) senses because they remain there while you work on attaching meaning to the stimulus. Auditory information is harder to process because it is so transient – it is gone very quickly. Then we add the aspect of auditory information being in a language code. Other than environmental noises, auditory stimuli require more cognitive energy to understand. Most of the challenges that negatively affect learning and functioning in the everyday world are in the area of auditory processing.

3. What is auditory processing?

When “auditory processing” was first introduced (Mylebust, 1954) it was used to describe children who had normal hearing but were struggling to understand auditory information presented to them. They could hear the words but had trouble attaching meaning to understand the message within the language. The term was very broad in its definition. It referred to interference with comprehension of language that could be based in language, academic learning, or listening skills. For decades the term “auditory processing” was defined as problems abstracting meaning from an auditory stimulus (Massaro, 1975), which encompassed many cognitive and language abilities.

As the discipline of audiology developed, professionals wanted to better differentiate the auditory and language components. The first step was to emphasize that the individual must have normal hearing acuity in the peripheral auditory system. In other words, the person can accurately receive an auditory stimulus but struggles to understand or interpret the signal. “Central auditory processing” was introduced (Keith, 1977) to specify that the deficits were based in auditory skills mediated in the central auditory nervous system (CANS). The difficulty in discriminating various features of the acoustic signal were subsequently interfering with comprehension of the message.

4. What do you mean by acoustic features of the signal?

When we analyze an acoustic stimulus, there are many aspects that contribute to the integrity of the sound. Pitch, loudness, speed of presentation, and the different phonemes all occur together very quickly. An individual needs to be able to discriminate the different sound segments to accurately attach meaning. For example, I need to be able to hear the difference in “p” versus “b” to know if the word I heard was “pat” or “bat”. My interpretation of the message will be confused if I can’t tell those sounds apart. The picture in my brain will be formed by how I hear and interpret a sound sequence. The sound sequence will have meaning based on the language code.

5. Can you give me some examples of the acoustic skills that are part of an auditory processing disorder?

An audiologist would look for poor performance in the ability to localize sound, the ability to discriminate different phonemes, trouble hearing when the signal is compromised by static or background noise, or trouble hearing when there is more than one signal at a time.

6. Are the acoustic features part of the definition for central auditory processing disorder?

Yes, audiologists and speech-language pathologists gradually acknowledged that there were acoustic, phonemic, and linguistic aspects to processing. Audiology focused on the acoustic and phonemic aspects of auditory processing. Neurologically their definition focused on moving the acoustic signal from the inner ear through the central auditory nervous system to the upper cortex. The definition for auditory processing is “the perceptual processing of auditory information in the central nervous system (CNS) and the neurobiological activity that underlies that processing and gives rise to electrophysiologic auditory potentials (ASHA, 2005a). Basically, auditory processing is the efficiency and effectiveness in how the central auditory nervous system utilizes auditory information.

7. Are “auditory processing” and “central auditory processing” the same thing?

Yes, there is agreement in audiology that those are synonymous terms. For a while central was included in parentheses, so you would see (central) auditory processing or (C)AP. This was to emphasize the focus on central auditory nervous system (CANS) skills when referring to an auditory processing disorder. The recommendation (ASHA, 2005b) was to drop central and just use auditory processing (AP) and auditory processing disorder (APD) without the use of central.

8. Who can diagnose an auditory processing disorder?

An audiologist is the only professional who can diagnose an auditory processing disorder. While numerous professionals might suggest that an individual has an auditory processing disorder, they are describing the types of activities that are problematic for a person. A teacher, psychologist or physician might observe that an individual is having trouble understanding what is said to them and state that they have an auditory processing disorder, but that is not a diagnosis. It is a professional opinion of what could be the problem. Referral for a formal evaluation should be considered.

9. What does the evaluation for assessing an auditory processing disorder involve?

The purpose of an auditory processing evaluation is to assess the integrity of the central auditory nervous system in a controlled discrete manner. The tests stress the auditory system by compromising the acoustic signal to see how the individual responds. Each audiologist designs a battery of tests that he or she believes will adequately assess the individual’s auditory processing ability. There are four types of procedures that can be used in a central auditory processing evaluation:

- Monotic/monaural – acoustic stimuli presented to one ear;

- Dichotic – different acoustic stimuli presented simultaneously to both ears, such as “hot” in the left ear and “dog” in the right ear at the same time;

- Binaural interaction – separate signals to each ear must be added together or separated, such as “m” to the left ear, “a” to the right ear, and “t” to the left to the word “mat”;

- Electrophysiological – these are neurological reflex tests that do not require a response from the individual; electrodes are attached to evaluate brain stem responses.

There is not a consensus battery within audiology regarding which skills should be included in an evaluation. However, the rule of thumb for diagnosis of an auditory processing disorder is a performance deficit of 2 standard deviations below the mean on two or more tests of the battery administered to the person.

10. What is the role of the speech-language pathologist in auditory processing disorders (APD)?

While an audiologist is responsible for diagnosing an auditory processing disorder, it is usually a speech-language pathologist (SLP) who is responsible for coordinating and providing treatment to address the auditory processing deficits. That is why it is important to know which auditory skills were significantly impaired that resulted in the diagnosis of APD. There are many aspects to an auditory processing evaluation that examine the person’s ability to discriminate various acoustic features. The SLP needs to work with the audiologist to identify the most pertinent aspects that will functionally make a difference.

11. What is the difference between language processing and auditory processing?

Processing an acoustic signal is very different than processing a linguistic signal. Auditory processing typically requires little to minimal interpretation of the auditory stimulus. Sometimes a simple repetition task will tell you that the signal was transferred accurately through the brainstem to the upper cortex. The central nervous system has incredible neurological redundancy that minimizes the possibility of deficits in transferring the signal to the temporal lobe. Most auditory processing disorders occur once the individual begins to discriminate and manipulate the acoustic features in the upper cortex at a phonemic level. The acoustic signal is usually not the source of the problem. The difficulty is when the individual tries to decode and interpret the message within the auditory signal. That is language processing. Language processing is the ability to attach meaning to the acoustic stimulus. It is the ability to understand the semantic and syntactic message encoded in the signal. Many of the learning difficulties experienced by children in an academic setting are based in difficulty processing language.

12. Who diagnoses language processing disorders?

The speech-language pathologist is responsible for conducting an evaluation to see if the deficits are in phonemic or linguistic aspects of processing. The speech-language pathologist will conduct assessment procedures to evaluate phonemic discrimination and manipulation of sounds as well as language comprehension. There is not one assessment instrument that will provide the necessary information, so the SLP must also rely on a battery of tests, like what the audiologists does in assessment. There are numerous phonemic and linguistic skills that are encompassed within language processing. The SLP should probe pre-linguistic phonemic discrimination as well as semantic linguistic skills that are age-appropriate for the individual. Some examples of phonemic assessment tools might be the Phonological Awareness Test or Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing. Language processing tests could include the Comprehensive Assessment of Spoken Language or Language Processing Test. The goal in the SLP assessment should be to identify the level of breakdown in the phonetic and/or linguistic areas to focus targeted intervention.

13. Can you summarize the continuum of processing disorders to differentiate the various aspects?

There are many different skills that are encompassed within processing auditory information. It can be overwhelming to a professional trying to figure what the specific deficits are that contribute to the challenges being experienced by the person. Clinically, it is easier to group the components of processing into three main types – acoustic, phonemic, and linguistic. First the acoustic stimulus must be received or perceived by the person. Second, it is transferred from the inner ear through the brain stem via the central auditory nervous system to the upper cortex. Then the temporal lobe becomes the primary cortical structure involved in decoding analyzing, and interpreting the auditory signal received. While the processing of auditory information is not completely a linear progression and there is certainly overlap, it helps to focus the assessment and intervention process if you group the major components of processing into acoustic, phonemic, and linguistic chunks. There is also overlap in professional responsibilities for evaluating processing skills in the continuum, which leads to some confusion in the diagnosis.

- Acoustic processing refers to the ability to receive the auditory signal and transfer it intact to the upper cortex. Then the person can work on understanding the message or meaning embedded in that sound sequence. If the signal become compromised or messed up during the neurological transference, then the person hears gobbledygook! That’s why they can’t understand what was said. Acoustic processing is the ability to discriminate the various features of an auditory stimulus. This area is the responsibility of an audiologist to evaluate.

- Phonemic processing refers to the ability to discriminate and manipulate the different sound segments of the language, specifically the consonants and vowels. It also overlaps into the grapheme symbols that represent those sounds. Phonemic processing is the foundation for literacy – reading, spelling, and written language. This is a critical area of processing that has a huge impact on academic performance. Children must be able to hear the different sounds, represent them with a letter, and sequence them to form words. Some confusion occurs in diagnostic labels since this area can be evaluated by both the audiologist and speech-language pathologist. If a phonemic processing disorder is evident to the audiologist, the diagnosis will be auditory processing disorder. If a phonemic processing disorder is evident to the speech-language pathologist, it is diagnosed as a language processing disorder. What is most important is to identify the specific deficit as being phonemic, rather than acoustic or linguistic so intervention is focused on the appropriate part of the processing continuum.

- Linguistic processing transitions into the semantic and syntactic aspects of language use. This is where the sound sequence received must be interpreted to result in pictures in the brain! The individual must have knowledge of the language code – or what certain sound sequences mean when a word is spoken. Language acquisition begins at a very concrete level of nouns and verbs that are easily seen and experienced. But language quickly transitions into abstract relationships and that’s when language processing becomes more challenging. Comprehension of language becomes more abstract and complex over time. Evaluation of language processing is the responsibility of the speech-language pathologist. The assessment tasks will vary based on the language expectations for the individual by age or development.

A visual summary of the continuum is provided below (Richard, 2019).

14. Is there any quick way to screen the continuum so I know where I need to spend my diagnostic time?

Yes. The Differential Screening Test for Processing (DSTP) (Richard & Ferre, 2006) was designed in collaboration with Dr. Jeanne Ferre, audiologist, to do a quick evaluation of the three major aspects of the processing continuum. It includes 3 subtests in acoustic processing, two subtests in phonemic processing, and three subtests in linguistic processing. This assessment instrument is designed to be administered by CD under headphone conditions in about 35 minutes. This allows the SLP to quickly look at the three main areas of processing (acoustic, phonemic, linguistic). If the individual fails any of the subtests, the SLP can spend more in-depth diagnostic assessment time in the focused area identified by the screening tool.

15. What are the essential components for treating processing disorders?

It is important to always have two main types of goals when working on processing disorders. The first area is to implement compensatory strategies to help the person cope with everyday expectations. These would be coordinated with a teacher or parents to provide a more supportive environment that increases the opportunities for the person to accurately understand and respond to auditory information. The second area is to address the specific skills that are weak or in deficit. These goals would be worked on directly with the individual in therapy. There are also several computer programs that can also be utilized to let the person work independently on processing skills outside of therapy, such as Hear Builder (Super Duper Publications) and Hooked on Phonics.

16. What are some of the skills and strategies to work on an auditory processing disorder?

Here are some examples of skills you might work on for an auditory processing disorder:

- Pitch identification– high pitched tones versus low pitched tones; pitch patterns and sequences.

- Speech in noise – identifying words presenting in noise and with competing messages.

- Phoneme discrimination – identifying consonants and vowels in isolation and syllables.

- Temporal processing– identifying if there is one phoneme or two based on rate of presentation.

- Auditory localization- identifying the direction of where sound is coming from.

Strategies to manage the auditory processing disorder in the environment would focus on ways to maximize or enhance the signal. Examples would include preferential seating, amplification, repetition, providing visual back-up to auditory information, and controlling background noise.

17. What are some of the skills and strategies to work on a phonemic processing problem?

Here are some examples of skills you might work on for a phonemic processing disorder:

- Auditory analysis/segmentation- Identifying specific phonemes in word positions, such as the first sound, last sound, middle vowel, or how many sounds are in a word.

- Auditory closure – filling in missing sounds, such as “peanut -utter and -elly”.

- Auditory synthesis/blending – putting isolated sounds together to form words.

- Auditory memory – ability to remember sequences of items or specific information.

- Auditory discrimination – ability to distinguish between sounds in words, such as identifying the first sound in a word or if two words end with the same sound.

- Rhyming – manipulating initial sounds while maintaining the rest of the word’s sound sequence.

Strategies to manage phonemic processing problems are similar to the auditory processing strategies that enhance or emphasize the sound features. In addition, provide visual cues such as the visual graphemes/letters to supplement the auditory information.

18. What are some of the skills and strategies to work on a language processing problem?

We could list innumerable specific language skills that could be addressed. A few major skills that are typical at the elementary level are the following:

- Concepts – identifying abstract features of size, shape, texture, time, quantity, quality.

- Categorization - grouping items by shared attributes, such as function, color, location.

- Antonyms & Synonyms – understanding word relationships of the opposite or same.

- Compare & contrast – identifying similar and different features between items.

- Multiple Meanings – recognizing different meanings of words based on context.

- Idioms – nonliteral meanings of language.

The important aspect in working on skills is to order the language goals in a hierarchy of complexity. For example, a student who has deficits in categorization needs to master that skill before they are ready to work on comparing and contrasting,

Strategies to enhance language processing include providing clues or hints to help a student retrieve information, teaching in a multi-modality style with visual materials and demonstrations to go with the auditory presentation, removing time pressure to encourage careful thinking time, and rephrasing, repeating, or expanding to clarify directions or information.

19. Can an individual have both an auditory and language processing problem?

Yes. An individual can experience any combination of deficits in a processing disorder. The person could have only a deficit in acoustic, phonemic, or linguistic skills. An individual could have deficits in two areas, such as auditory and phonemic processing. In this case, the person would be struggling with the building blocks of the auditory information that require them to discriminate acoustic features. This would impact reading, spelling, and written language, but they could be competent in everyday functional situations in understanding verbal language. When an individual has deficits in all three areas, progress is generally slow and academic performance is significantly impacted (Richard, 2017).

20. Is treatment effective for addressing processing disorders?

The research on treatment efficacy for processing disorders is very mixed. Because the disorder is so broad and includes many different aspects of auditory and language skills, it is difficult to show strong treatment effects. There is not good agreement in how to define the disorders within the disciplines of audiology and speech-language pathology. Consequently, the group of individuals diagnosed with a processing disorder who might be included in a research study tend to be very heterogeneous, minimizing the opportunity to demonstrate strong treatment efficacy. When a processing disorder is suggested, it is important to clinically evaluate the specific deficit skills that contribute to that diagnosis. The terminology of “auditory processing disorder (APD)” or “language processing disorder (LPD)” can be misleading, depending on who introduced the label. In both cases, APD or LPD, multiple skills are encompassed under that label. Intervention will only be effective if the treatment is focused in the major area of deficit (acoustic phonemic, linguistic) and targets functional skills.

References

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (2005a). Central auditory processing disorders: The role of the audiologist (Technical report). Retrieved from www.asha.org/policy.

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (2005a). Central auditory processing disorders: The role of the audiologist (Position statement). Retrieved from www.asha.org/policy.

Keith, R. (1977). Central auditory dysfunction. New York, NY: Grune & Stratton.

Massaro, D. (1975). Understanding language: An information processing analysis of speech perception, reading, and psycholinguistics. New York, NY: Academic Press.

Myklebust, H. (1954). Auditory disorders in children: A manual for differential diagnosis. New York, NY: Grune & Stratton.

Richard, G. (2019). Language processing versus auditory processing. In D. Geffner and D. Ross-Swain (Eds.), Auditory processing disorders: Assessment, management, and treatment (3rd ed., pp.215-232). San Diego, CA: Plural.

Richard, G. (2017). The source: Processing disorders (2nd ed.). Austin TX: Pro-Ed.

Richard, G. & Ferre, J. (2006). Differential screening test for processing. East Moline, IL: LinguiSystems (PRO-ED).

Citation

Richard, G. (2021). 20Q: A continuum approach for sorting out processing disorders. SpeechPathology.com Article 20495. Available at www.speechpathology.com